|

June 2015, Volume 37, No. 1

|

Original Article

|

|

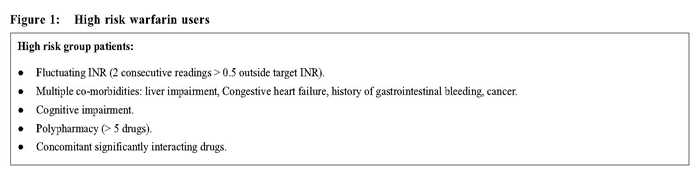

A review on warfarin therapy at primary care settingsLit-ping Chan 陳列萍,Maria KW Leung 梁堃華,Augustine T Lam 林璨 HK Pract 2015;37:23-29 Summary Objective: To review the compliance for a warfarin management guideline, standard of care, and identify opportunities for improving medication safety. Design: Cross-sectional study. A guideline on management of patients on warfarin therapy was carried out by the Family Medicine Department of New Territories East Cluster (NTEC FM) of the Hospital Authority of Hong Kong in 2013. Review criteria were set according to the guideline. Subjects: All warfarin users followed up in the 8 primary care clinics (PCC) of NTEC FM within the period from 1 January, 2013 to 30 April, 2013. Main outcome measures: compliance to the criteria and prevalence of patients with International Normalised Ratio (INR) within target range. Results: All 108 warfarin users had computer reminders set. 102 (94.4%) were issued with warfarin education booklets. 4 (3.7%) high risk patients had not been referred to a pharmacist for counselling. 106 (98.1%) had their INRs checked before the consultation. 82 (77.4%) had INRs within target range. 12 (11.1%) patients did not have dosage adjusted according to the titration table. Conclusion: The review showed high compliance to the guideline on the process of care for patients on warfarin. The standard of care was high. However, there was still room for improvement in warfarin titration. Keywords: Warfarin therapy, Primary care clinics 摘要 目的:評審對華法林治療指引的跟從情況和治療標準,找出改善用藥安全的機會。 設計:橫切面研究。在2013年,香港醫院管理局新界東聯網的家庭醫學部 (NTEC FM) 設計了使用華法林的治療指引,並且以此為依據設定了評審標準。 研究對象:2013年1月1日至4月30日期間,所有在NTECFM的8間基層醫療診所 (PCC) 跟進的正在使用華法林的患者。 主要測量內容:審查標準的合規情況以及患者達到國際正常化比值 (INR) 目標範圍的程度。 結果:所有108個使用華法林的病人都設置了電腦提醒。102人 (94.4%) 獲派華法林教育小冊子。4人 (3.7%) 高風險的患者未曾轉介給葯劑師做諮詢。106人 (98.1%) 在覆診前檢查了INR值。82人 (77.4%) 的INR值在目標範圍之內。12人 (11.1%) 沒有根據劑量表進行調整藥量。 結論:評審顯示,治療過程中,對服用華法林的指引的跟從程度很高,治療的達標率也很高。但是,華法林的劑量調整仍然有改進的空間。 主要詞彙:華法林治療,基層醫療診所 Background Warfarin is effective in preventing strokes and other thromboembolic complications in patients with a history of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), atrial fibrillation (AF) and valvular heart disease. 1-4 However, it has a narrow therapeutic range with risks of life-threatening bleeding events from over-anticoagulation5-6 and thrombo-embolic complications from underanticoagulation. Evidence suggests that the rate of major bleeding in practice is about 7-8% per year.7 In the New Territories East Cluster (NTEC) of Hospital Authority (HA), warfarin is only initiated by hospital specialists and patients on warfarin were then transferred to primary care clinics (PCC) after stabilisation. Because of the narrow therapeutic range, the need for frequent monitoring, co-administration of multiple drugs and food interactions, and the risk of bleeding, it is crucial to have a systematic approach to ensure efficacy and minimise adverse effects.8-12 A guideline on the management of patients on warfarin therapy was introduced by the cluster Committee on Quality and Safety in the HA NTEC in 2012.13-14 The guideline was adopted in the PCC in NTEC in May 2013. The guideline includes the following recommendations: 1) Setting electronic reminders in the computerised clinical management system (CMS) regarding which clinic is issuing warfarin, the indication and date of initiation. Reminders will pop up whenever the clinician opens the CMS of warfarinised patients, alerting doctors about the use of warfarin, reducing the risk of double prescriptions and increasing the awareness for possible drug-drug interactions. 2) Issuing warfarin education booklets. This contains various clinical information (indication, target INR, latest INR, date of commencement, proposed duration of treatment, dose adjustment record) and lay-information (side effects, storage, what to do after drug omission, foods or drugs to be avoided, when should bleeding tendencies be suspected, and list of foods with high vitamin K content). The booklet has two functions; first to remind and educate patients about warfarin; and second to serve as a communication tool between private and public doctors. 3) Referring high risk patients14 (Figure 1) to a pharmacist for counseling and education. As well as reiterating the contents of the booklet, the pharmacist will review for possible food or drug interactions, drug dose and compliance. Further communication with a doctor will be organised if dose adjustment is required.

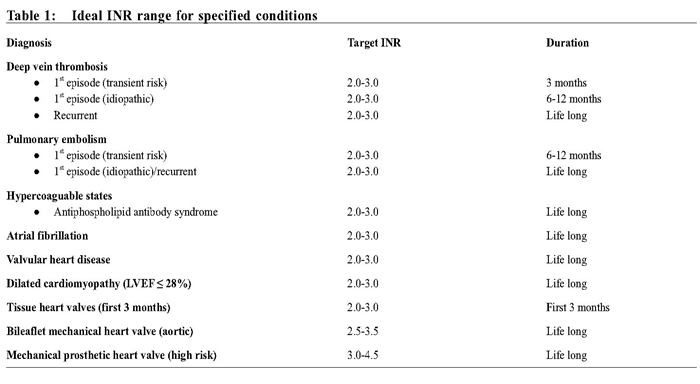

4) Monitoring INR before each consultation. Patients are reviewed in our clinics regularly every 3 to 4 months with INR checked a few days before the follow up date. 5) Adjusting warfarin dose according to ideal INR ranges (Table 1) and the standardised titration table (Table 2).14

The warfarin management workflow was explained to all doctors and nurses in NTEC during the monthly clinic meetings in May 2013. Five criteria for reviewing guideline compliance were established with consensus reached among all staff. This paper aims to:

Methods Design, sampling and data collection A list of patients prescribed with warfarin from the 8 PCCs in NTEC from 1 January 2013 to 30 April 2013 was obtained by searching the clinical data analysis retrieval system (CDARS). Patients were included if they were followed up regularly at our PCCs and were excluded if they were followed up at a hospital specialty out-patient or private warfarin clinic. The most recent clinical notes of warfarinised patients were reviewed by our investigators in November 2013. The investigators were a group of Family Medicine specialists. Data was collected using a standardised excel file and analysed with SPSS statistics version 22.

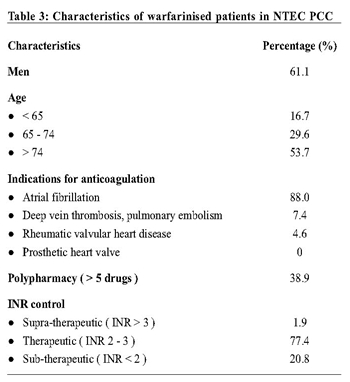

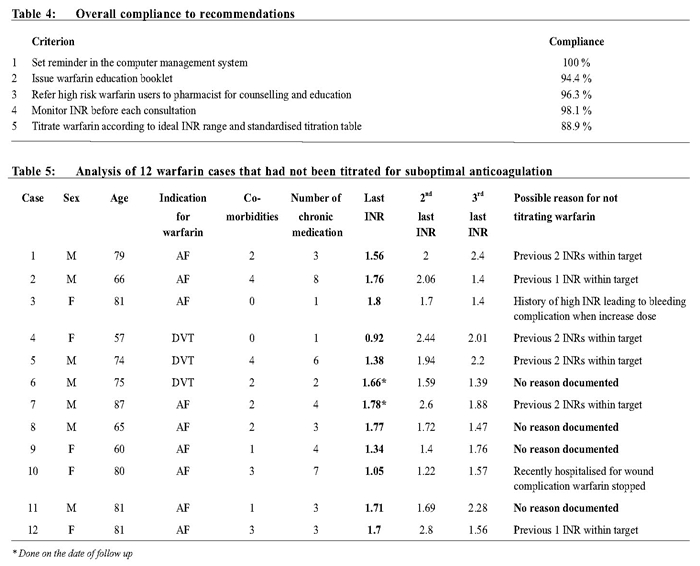

Outcome measures Compliance to the five guideline recommendations and prevalence of patients with INR within target range was used as outcome measures. Non-compliant cases were further analysed. Results During the review period, 141 warfarinised patients were identified; 33 (23%) were excluded because they were regularly followed up at a hospital or private warfarin clinics. The warfarinised patients in NTEC PCCs were predominantly elderly people. The most common reason for anticoagulation was AF. 18 (16.7%) cases had AF coexisted with stroke or transient ischaemic accident. There was no patient having prosthetic heart valve. Cases with prosthetic heart valve were generally of higher risk and being monitored at a hospital instead of in PCC. 42 (38.9%) patients had polypharmacy, taking more than 5 kinds of chronic medications. The mean number of chronic medication was 5.0 per patient. The target INR for all analysed patients was 2 to 3. Within the review period, 2 (1.9%) cases did not have their INR checked before follow up. For those who had their INR monitored, most cases, 82 (77.4%), were within the target range. The compliance to criteria 1 - 4 was good overall, with compliance greater than 95 % (Table 4). For criterion 5, 12(11.1%) patients did not have dosage adjustment according to the titration table. Among these cases (Table 5), 6 (50%) had previous INRs within the target range. 2 (16.7%) were not titrated because of advanced age with history of fluctuating INR or bleeding complication. 4 (33.3%) were not titrated with no documentation on the reasons.

Discussion Setting reminders appear to be readily accepted and considered useful by frontline doctors, given the full compliance found in this review. But booklets were not given out to all patients, probably because some patients were considered illiterate or too old to understand the information. However, booklet can serve as educational materials both for patients and their relatives, and can be a form of communication between doctors. Frontline doctors should be reminded of these uses in order to promote its use. A small number of high risk cases were not referred to the pharmacist for counselling without documentation of reason. Lack of consultation time or unawareness of the service was possible. Some patients reported that they had received similar education in the past and, therefore, were not keen for such a referral. Doctors were encouraged to utilise the counselling service so as to improve the knowledge of medication safety and empower self-care. For patients who were too old or fragile to travel, individual counseling could be considered. For anticoagulant management, most cases had their INR checked before the consultation. Doctors were recommended to check INR at the time of consultation for patients who defaulted the prearranged test. If the INR result was out of the target range, early titration could be arranged to avoid delay in management. Regarding the most important part of anticoagulation therapy, proper titration of medication to achieve target anticoagulation level, there was still room for improvement. Barriers for titration of warfarin can be multiple.15,16 Patients’ medical and social backgrounds were considered. Quite a number of patients in the PCC were fragile elderlies with multiple co-morbidities. Many patients took various medications and were at risk of fall or bleeding complications. Some had a history of gastrointestinal bleeding or complications, like in case 3 and 10. Some had poor activities of daily living and a lack of social support. These all affected the doctors’ decision with medication titration. On the other hand, some clinicians may not be aware of the importance of adequate anticoagulation or has a lack of knowledge in medication adjustment. Despite repeated sub-therapeutic anticoagulation, the warfarin dosage was still not titrated like in case 6,8,9 and 11. Potential barriers to warfarin titrations should be analysed and addressed. Training on warfarin titration should be given to frontline doctors to enhance safe prescription. In patients with fluctuating INRs, novel anticoagulants like dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban should be considered as effective and convenient alternatives to warfarin for the prevention of stroke in patients with non-valvular AF. 2,17 The British Committee for Standards in Haematology (BCSH) 2005 recommends that the target INR be within +/-0.5 units at least 60% of the time, i.e. a time in therapeutic range (TTR) of 60%. TTR is most commonly estimated by using one of three methodologies: calculating the fraction of all INR values that are within the therapeutic range; using the “cross-section of the files” methodology, which assesses the fraction of patients with an INR in range at one point in time compared the total number of patients who had an INR measured at that point in time; or applying the linear interpolation method of Rosendaal et al which assumes that a linear relationship exists between two INR values and allocates a specific INR value to each day between tests for each patient. Our TTR, 77.4%, was above the standard. It was also compatible with some audits in PCCs elsewhere. 18-21 TTR is a common surrogate marker of the quality of anticoagulation control. A re-audit in the future using TTR can evaluate how well PCC providers manage the anticoagulation and establish benchmarks to ensure there is an acceptable standard of care. The overall compliance to the review criteria was promising. Benefit could be seen in following suggested workflow of warfarin management not only for patients but also for doctors too. Patients would be more informed and empowered about the use of warfarin. By using the reminder and booklet, the communication between different health care providers would be enhanced. There is better continuous patient care from a hospital setting to primary care, whether private or public. Moreover, by adopting the dosing and monitoring guideline, there should be less chance of overor under- anticoagulation which could result in developing complications. Medication incidents are expected to be reduced through better understanding and compliance of the suggested workflow. Doctors in PCC can assist in reducing the workload of hospital medical specialists by taking over the stable cases, in addition to providing continuous holistic patient care. Limitations The review was limited by its descriptive nature and lack of clinical outcome analysis like efficacy and adverse effect such as thromboembolic or haemorrhagicevents. Further cohort study is necessary. Due to the small sample size, we were not able to find any doctor or patient association factors. Warfarin has a narrow therapeutic window and has been associated with many drugs or foods interaction. Future assessment on patients’ or care-givers’knowledge on warfarin treatment after receiving counseling could be of value to ensure medication safety. Since warfarin is a high risk medication, regular audit on compliance to management workflow should be an integral part of safe anticoagulant management service. Laboratory measurements, dosing, level of therapeutic INR control, clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction and clinic administration (e.g. follow-up on patients failing to attend clinic) should also be systematically reviewed. Standards outlined by the BCSH could be used as reference for future review. 9,22,23

Conclusions The review showed a high standard of care in managing patients on warfarin in PCC. There was high compliance to the guideline on process of care. Given the unique multiple co-morbidities of PCC patients and the inherent high risk nature of warfarin therapy, regular audits in warfarin management should be established in order to maintain an acceptable standard of care, ensure efficacy and minimise complications. Acknowledgments: Dr Heung-wing Li, Dr Man-kei Lee and Dr Fong-tat So for data collection. Lit-ping Chan, MBBS (HK), FHKCFP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Correspondence to: Dr Lit-ping Chan, Department of Family Medicine, Prince of Wales Hospital, New Territories, Hong Kong SAR, China. References

|

||