|

June 2015, Volume 37, No. 1

|

Original Article

|

|

Home blood pressure monitoring of hypertensive patients in a primary care clinic in Hong Kong: - a cross sectional surveyLap-kin Chiang 蔣立建,Lorna Ng 吳蓮蓮 HK Pract 2015;37:3-13 Summary Objectives: Design: A cross-sectional survey. Subjects: Adult Chinese hypertensive patients follow up at a regional primary care clinic of Hong Kong. Main outcome measures: Results: 57 male and 71 female patients completed the questionnaire. 65.6% of patients owned a BP machine at home, and 58.5% performed home BP monitoring. 71.9% had never learned how to measure BP. Among those who did not own a home BP machine, 36.4% claimed that BP machines were too expensive, 36.4% claimed that they did not know how to measure BP. Among 65 patients who took and completed the self BP measurement competency test, 97% and 55.3% passed the written and practical test respectively. 30.8% of patient failed to position the cuff correctly in the practical test. Conclusion: 58.5% of hypertensive patients in a primary care clinic of Hong Kong performed home blood pressure monitoring, while 55.3% of them were considered to be competent in performing self-blood pressure measurement. Keywords: Home blood pressure monitoring, hypertension, primary care 摘要 目的: 設計:橫斷面調查。 研究對象:香港某間基層醫療診所的華藉高血壓病人。 主要測量內容: 結果:57位男性和71位女性高血壓病人完成了問卷調查。65.6%病人的家中擁有血壓機,58.5%家居有進行血壓監測。71.9%病人表示從未學習過如何測量血壓。家中沒有血壓機的病人,36.4%表示因為血壓機太貴,36.4%表示他們不知道如何量血壓。65例高血壓患者完成了自我血壓測量的評核測試,其中97%通過了筆試,另外55.3%通過了實際測試。實際測試中,30.8%的病人未能將臂束帶放置在正確位置。 結論:香港某間基層醫療診所的華藉高血壓病人中,58.5%進行家居血壓監測。55.3%病人通過了自我血壓測量的評核試。 主要詞彙:家居血壓監測,高血壓,基層醫療 Introduction Hypertension remains a key risk factor for cardiovascular disease, yet only about half of patient on treatment for hypertension have their blood pressure controlled to current recommended levels.1,2 Hong Kong Population Health Survey 2003 - 04 revealed that around 27% of the population aged 15 or above had increased blood pressure. 3 Among those ever diagnosed with hypertension, 70% were prescribed blood pressure lowering medication, but only about 40% of those receiving treatment group attained control of their blood pressure. 4 Numerous international agencies recommend home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) in their published guidelines, including the World Health Organisation – International Society of Hypertension, 5 the US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (JNC 7 report),6 the American Heart Association and the American Society of Hypertension (AHA/ASH),7 the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and the European Society of Cardiology,8 and the British Hypertension Society.9 The Hong Kong Reference Framework on Hypertension Care in Adults in Primary Care Settings recommended home blood pressure monitoring and issued the guide on how to measure blood pressure using digital monitors.10Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials have shown that home blood pressure monitoring can lead to blood pressure (BP) control that is at least as good as office-monitored blood pressure; HBPM can also result in better BP control, perhaps as a result of better adherence to treatment as well as detection and treatment of masked hypertension.11-14 According to Bancej et al,15 45.9% of Canadian adults with hypertension monitored their blood pressure at home. 61.7% of the hypertensive patients in Singapore were aware of HBPM but only 24% of them used it. 16 No local studies have been performed to document the prevalence and use of HBPM in Hong Kong primary care setting.17 HBPM is often used without proper medical advice, thus measurements can be inaccurate and adversely influence clinical management.17 Existing evidence suggests that inadequate knowledge, poor skill and inaccurate equipment use are widespread among those who are practising self BP monitoring.18,19 Objectives 1. To evaluate the prevalence of home blood pressure monitoring

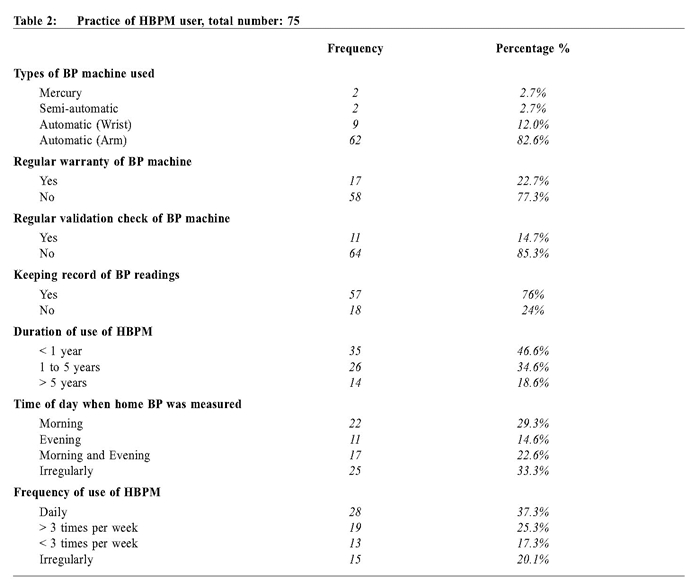

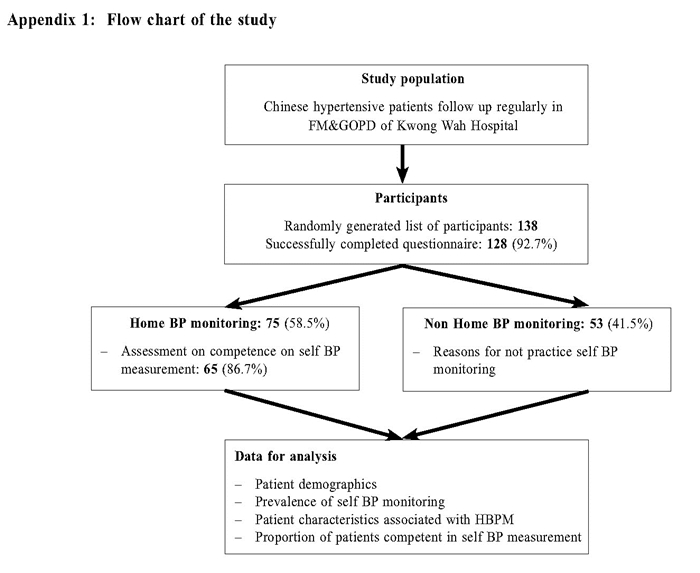

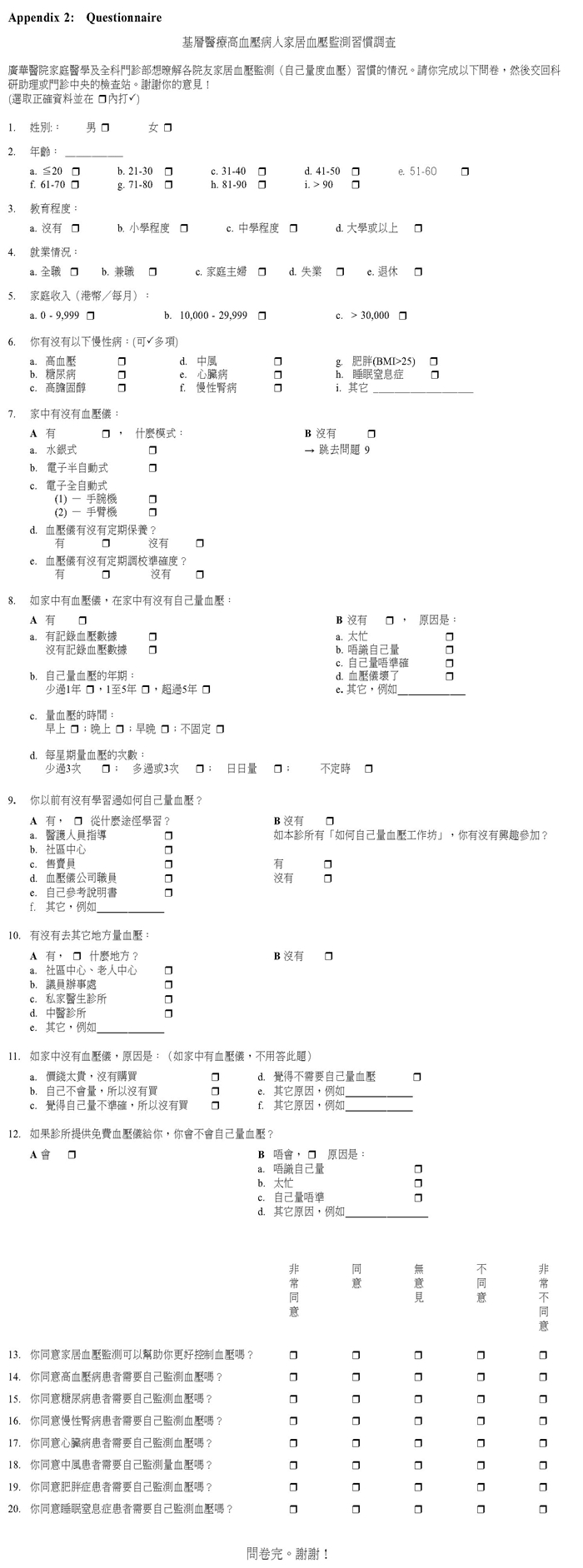

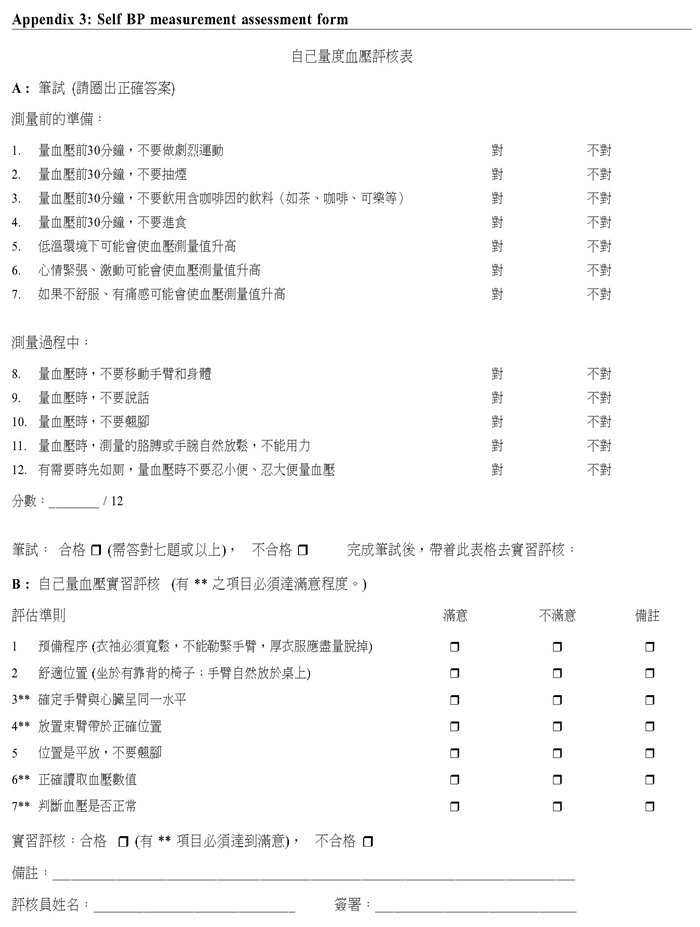

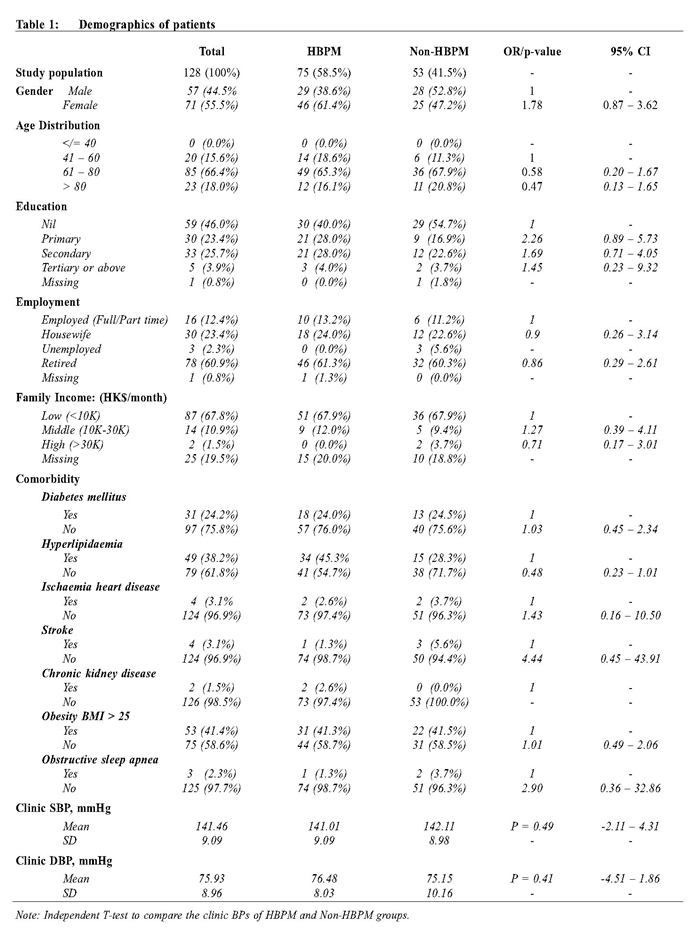

among hypertensive patients in a primary care setting. Methods This is a cross-sectional study, involving adult Chinese patients with hypertension followed up in the Family Medicine and General Outpatient Department (FM & GOPD) of Kwong Wah Hospital. (Appendix 1: Flow chart of the study)A list of hypertensive patients, aged 18 or above were randomly generated from the department’s hypertension patient registry. Patients who consented to the study were invited to complete the questionnaire during their follow up attendance. (Appendix 2: Questionnaire) Patients who could not physically perform HBPM were excluded. Patients performing home blood pressure monitoring were invited to measure their BP exactly as they would at home and to provide their readings. The skills and competence of self blood pressure monitoring were assessed by 3 voluntary retired nurses according to a standardised evaluation form (Appendix 3: Evaluation form), which included written and practical procedures on self BP measurement. Survey instrument As there was no validated local questionnaire available, author developed the questionnaire with reference to Bancej et al15 and Tan et al16 study. A core group including doctors and nurses were invited to comment on the questionnaire for relevance and content validity. The questionnaire was pilot-tested in a group of 5 patients for face validity.Self BP measurement evaluation Competence in self BP measurement was assessed using a standardised protocol, which was divided into written and practical sections. The evaluation form was adapted from the evaluation form for Health Care Assistants of the Hospital Authority, and with reference to recommendations issued by the Hong Kong Primary Care Office10 and the Canadian Hypertension Education Programme.20 After test trial with hypertensive patients and further refinements, the evaluation form was finalised with consensus among the research team.Sample size estimation There were around 7,000 hypertensive patients in the registry of FM & GOPD of KWH. Assuming a prevalence of some 30% patients who performed home BP monitoring with 10% margin of error and 95% confidence level, the sample size was calculated to be 96.21 The final sample size of 138 patients was taken in, assuming a 30% attrition rate.Statistical analysis Descriptive statistics including the mean, standard deviation, frequency and percentages will be used to summarise the baseline characteristics and outcome measures. Chi-square test and multivariable analysis with regression were used to assess the predictive patient characteristics associated with use of HBPM. All analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 19 (SPSS Inc, United States).Research ethics The study was approved by the Hospital Authority, Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics Committee. (KW/EX-12-088 (55-09))Results 57 male (44.5%) and 71 female (55.5%) patients completed the questionnaire. Their demographics were summarised in Table 1. 24.2%, 38.2% and 41.4% of patients had coexisting diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia and obesity respectively. Home BP monitoring 84 patients (65.6% of total) owned a BP machine at home. Only 75 patients (58.5% of total) performed home blood pressure monitoring. The pattern of HBPM practice was summarised in Table 2. There were no significant differences in blood pressure levels between users and non-users of HBPM.

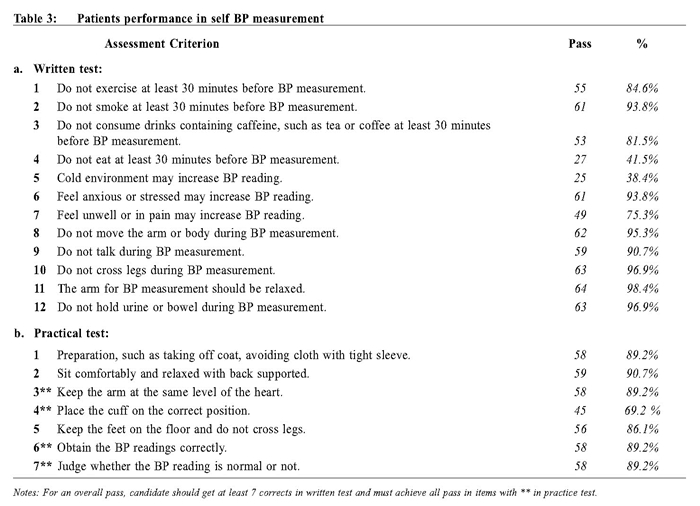

Most HBPM users (82.6%) used an arm type automatic BP machine. 22.7% had a regular warranty while 14.7% had regular validation for their BP machines. Among them, 76.0% kept BP records after measurement. 22.6% measured their BP both morning and evening, while 33.3% performed it irregularly. 62.6% monitored their BP at least 3 times per week. 36 patients (28.1% of total) claimed that they had learned how to perform self-BP measurement. Among these, 25.0% learned it from health care professionals, while 29.4% just had self-learning from BP machine manual. 76 patients (59.3% of total) expressed willingness to attend BP measurement workshops if available in the clinic. Univariate analysis showed that HBPM users tend to be females, younger, educated, employed or from middle family income groups, although none of the factors reached statistical significance. Multivariable regression failed to find any significant relationship between socioeconomic status and HBPM usage. Reasons for not having HBPM 44 patients (34.3% of total) did not own a BP machine and therefore never performed HBPM. Among them, 16 patients (36.4%) reported that BP machines were too expensive, while another 16 patients claimed that they did not know how to measure BP by themselves. 10 patients (22.8%) did not see the need for performing self BP monitoring. 9 patients owned BP machines but did not practise HBPM. One patient explained that he was too busy while another patient claimed that he did not know how to operate the BP machine. The remaining patients did not give specific reason for not practising HBPM. If free BP machine was provided to non HBPM users, 15 patients (34.1%) among those who did not own BP machine claimed that they would perform home BP monitoring.Self BP measurement evaluation 86.6% (65/75) completed the self BP measurement evaluation. 97% passed the written test while 55.3% passed the practical test. Their performance in each assessment items were summarised in Table 3.

In the written assessment, only 41.5% knew they should not eat 30 minutes before BP measurement and 38.4% knew that cold environment might increase BP reading. 24.7% did not know that measured BP would be increased if patient was feeling unwell or in pain. For practical assessment, 30.8% failed to position the cuff correctly. 10.8% could not obtain the BP readings from the BP machine correctly, and another 10.8% could not judge whether the BP reading was normal or not. Discussion A survey conducted in USA revealed that the proportion of patients owning a monitor machine had increased from 49% in year 2000 to 64% in 2005, while the number of patients monitoring their BP at home had increased from 38% in year 2000 to 55% in 2005.22 The progressive increase of HBPM over time is the consequence of the large and expanding market of automated BP devices for home measurement. 23 In our study, 65.6% owned BP monitor and the prevalence of HBPM was 58.5%, which was higher than Singapore16 (24%) and Canada15 (45.9%). It was probably due to broad availability of electronic BP measurement devices which led to their widespread usage. In Tan’s study, 13 the prevalence of HBPM users in the high and middle-income groups were significantly higher when compared to low income group. In Cuspidi C study, 24 those practising HBPM were more often younger, men and had a higher educational level. Both bivariate and multivariate analysis in our study did not find any socioeconomic factor associated with likelihood of HBPM. The reason for this difference was not clear, further study with adequate power may be required to confirm the findings. Cost, lack of confidence, knowledge and skills were identified to be barriers against self BP monitoring. However, patients generally agreed on the importance and need of HBPM and were willing to learn and practise HBPM. There was a lack of formal or structured training conducted by health care professionals to educate patients on self-blood pressure monitoring. Merrick reported that 53% of their study participants had never received instruction in the use of BP monitors. 19 According to Bancej CM, 15 receiving instruction from a health professional was most strongly associated with performing HBPM. The self-appointment system in both public and private primary care created readily available opportunities to offers HBPM education. Primary health care providers should therefore encourage patients to self-monitor their BP and provide formal instruction on BP measurement. This is the first study looking into the prevalence of HBPM in Hong Kong’s primary care. Our results will be useful for healthcare providers in formulating promotional activities on self-blood pressure monitoring. Our results highlighted that the majority of patients had not received formal training on self BP monitoring and a significant proportion were incompetent in performing self BP measurement. Health care providers must therefore ensure the reliability and accuracy of patient’s who presented home BP readings, especially if those readings were pivotal in clinical decision making. Limitation This study only involved patients from one primary care clinic, thus limiting the generalisability of our results. The reliability and validity of the survey instruments, including questionnaire and self BP measurement evaluation form were not fully evaluated, which may affect survey accuracy. In this survey, the HBPM group did not show significant better clinic BP control than the non HBPM group, the reason for this was not sure. In Fung et al study conducted in the public primary health care setting of Hong Kong concluded that the structured HBPM education programme has the potential to improve patient BP control at short term.25 Well planned randomised controlled trial may be conducted to assess the effect of HBPM on clinic BP control of Chinese hypertensive patients. Conclusion This cross sectional study reveals that 58.5% of hypertensive patients in a primary care clinic of Hong Kong perform home blood pressure monitoring. Around half of them (55.3%) were considered as competent in performing self-blood pressure measurement; therefore, health care providers should be aware of the reliability and accuracy of patients presenting home blood pressure readings.

Acknowledgmentt The authors would like to thank retired nurses Ms BC Ng, Ms YF Tsang and Ms WH Ho for helping to perform self BP measurement assessment, and thank Ms Emily Ho for helping in statistical analysis. This study was given a grant by Tung Wah Group of Hospitals (TWGHs) Research Fund. Authors would like to thank TWGHs’ support and generosity.

Lap-kin Chiang, MBChB (CUHK), MFM (Monash)

Resident Family Medicine and General Outpatient Department, Kwong Wah Hospital Lorna Ng, LMCHK, MPH (CUHK), FHKCFP, FHKAM (Fam Med) Senior Medical Officer i/c Family Medicine and General Outpatient Department, Kwong Wah Hospital Correspondence to: Dr Lap-kin Chiang, Family Medicine & General Outpatient Department, 1/F, Tsui Tsin Tong Outpatient Building, Kwong Wah Hospital, 25 Waterloo Road, Mongkok, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China. References

|

||