|

June 2015, Volume 37, No. 2

|

Original Article

|

|

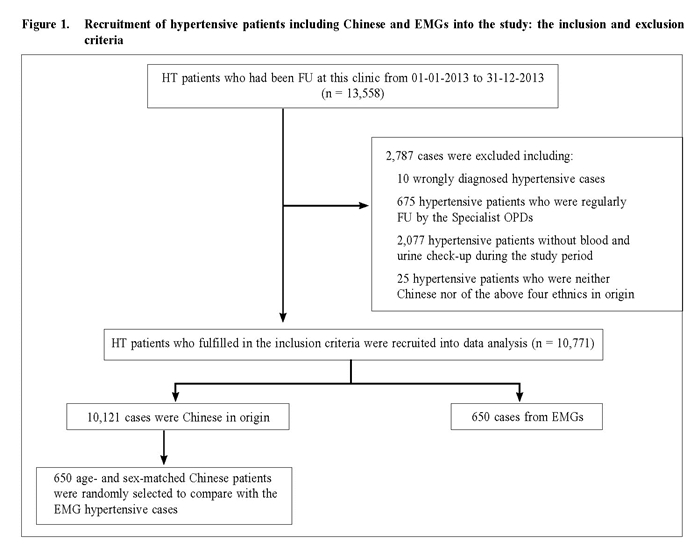

Management of hypertension in Hong Kong's ethnic minority groups: any gaps in blood pressure control?Catherine XR Chen 陳曉瑞, King-hong Chan 陳景康 HK Pract 2015;37:59-65 Summary Background: About 95% of Hong Kong's population is Chinese; the remaining includes various ethnic minority groups (EMGs). Previous studies had shown that hypertension (HT) affected certain ethnic groups differently. However, in Hong Kong, data on the control of hypertension among ethnic minority patients is lacking. Objectives: To identify the demographics and compare the disease control of EMGs and Chinese hypertensive patients managed in primary care, and to explore possible strategies to improve management of hypertension among the EMGs.Design: A cross-sectional comparative study. Design: Retrospective case series study. Subjects: Hypertensive patients among Chinese and EMGs who were regularly followed up at one General Outpatient Clinic of Kowloon Central Cluster of the Hospital Authority and with annual assessment done between 01/01/2013 to 31/12/2013. Main outcome measures: Their demographic data, biochemical parameters [serum fasting sugar (FBS), creatinine (Cr) and lipid profile], blood pressure (BP) and co-morbidities were retrieved by reviewing the medical record from the clinical management system (CMS). Student’s t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used for analysing continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical data. Results: Among 10,771 HT patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria, 10,121 patients (94.0%) were Chinese in origin and 650 (6.0%) were EMGs. Hypertensive EMGs were younger but more obese and had a higher prevalence of diabetes (all had P < 0.001). Their BP control was poorer than age-and sex-matched Chinese patients (P < 0.001). They also had lower high density lipoprotein level (HDL) and higher FBS and triglyceride levels (all P < 0.001). Within the EMGs, Pakistanis were found to have particularly poorer glycaemic control, while Nepalese had poor diastolic BP control. Conclusion: Compared with Chinese hypertensive patients, hypertensive EMGs were younger but more obese. Deficiencies existed in their management. Culturally tailored healthcare interventions are required to promote effective management among this group of patients. Keywords: hypertension, ethnic minority groups, primary care, co-morbidity, blood pressure control 摘要 背景及目的:香港大約 95%人口是華人,其餘來自少數族裔。以往的研究表明,不同族裔群體受高血壓的影響不同。然而,香港缺乏少數族裔高血壓患者的診治數據。此研究檢視與比較基層醫療診所覆診的高血壓病人中,華人以少數族裔患者的流行病學資料及高血壓的臨床治療狀況,並探討可以改善少數族裔高血壓患者的綜合臨床診治策略。 設計:回顧性病例研究 研究對象:2013年1月1日至 2013年12月31日期間,在香港醫院管理局九龍中聯網管轄下一間賽馬會普通科診所,定期覆診並參與年度檢查的華籍及少數族裔高血壓患者均被納入本研究範圍。 主要測量內容:他們的基本流行病學資料,生化指標包括:空腹血糖、血清肌酐和血脂以及血壓控制和合併症情況,並進行分析。 t檢驗( t-test)和變數分析 ( ANOVA)以分析計量資料,卡方檢驗用來分析計數資料。所有統計學測試都是雙邊檢定, P < 0.05表示數據有統計學顯著差異。 結果:共有 10,771名高血壓患者符合納入標準,其中 10,121名( 94%)為華人,另 650名( 6%)來自少數族裔。與華籍高血壓患者相比,少數族裔的高血壓患者較年輕和肥胖,且較多人同時患有糖尿病( P值均 < 0.001)。血壓控制明顯比年齡和性別相似的華籍患者差,且空腹血糖較高(P < 0.001)。血脂控制方面,兩組的總膽固醇和低密度脂蛋白的水準相近,但少數族裔患者的高密度脂蛋白水準明顯較華籍患者低,而甘油三酯濃度則明顯較高(兩者的 P值均為 < 0.001)。本港四大少數族裔中,巴基斯坦籍患者有較高的平均空腹血糖,而尼泊爾籍患者的舒張壓控制最差。 結論:少數族裔群體是香港人口的重要組成部分。與華籍高血壓患者相比,少數族裔高血壓患者更年輕和較為肥胖,尤以血壓控制未見理想。本研究建議為少數族裔群體制定有其族裔特點的綜合高血壓診治計劃,加強教育宣傳,以進一步提高臨床療效和改善少數族裔高血壓患者的長期健康狀況。 關鍵字:高血壓病,少數族裔,基層醫療,合併症,血壓控制 Introduction Ethnic minorities are an important composite of the Hong Kong population. According to the 2011 Hong Kong Census, about 95% of our population is Chinese; the remaining consists of ethnic minority groups (EMGs) mainly from Asia, such as India, Philippines, Nepal, Pakistan and Indonesia.1-2 Previous studies have shown that ethnic background plays an important role in the management of hypertension3 with substantial ethnic differences in cardiovascular mortality.4 For example, studies comparing the incidence of newly diagnosed hypertension, and subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease outcomes among South Asian, Chinese and white patients revealed that South Asian patients had higher rates of hypertension compared to other ethnic groups.5 South Asian and Chinese patients had a lower risk of death and developing cardiovascular outcomes compared to whites. Other studies have also shown that South Asian people have a much higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD), occurring at an earlier age and associated with high morbidity and mortality.6 Social deprivation with limited access to health services and difference in health care systems can further increase the risk of developing hypertension and its complications. Improving the quality of care for chronic disease is an essential component of community healthcare. Locally, a significant proportion of hypertensive patients (both Chinese and EMGs) are followed up at Government General Out-Patients Clinics (GOPCs) in the Hospital Authority (HA). The clinic where the author has been working is one of the biggest GOPCs in the Hospital Authority, located in the central Kowloon area where most of the South Asian minorities including Indians, Nepalese and Pakistanis reside in. As with most GOPCs, chronic diseases including hypertension comprise more than 50% of our annual attendances. Data concerning hypertension control among local hypertensive EMGs are lacking. This study aims to address this knowledge gap by identifying EMGs’ demographics and to compare the hypertensive control of EMG hypertensive patients with Chinese hypertensive patients managed in our GOPC, and to explore possible strategies to improve future care. Methodology According to a pilot study carried out in early 2012, the top four EMGs regularly followed up in our clinic were Nepalese, Indian, Filipino and Pakistani. Regular follow up (FU) is defined as returning to our clinic for chronic disease management on a regular basis (every 1-4 months). Very few Caucasians or other Asian ethnicities such as Japanese and Koreans had regular FU here and were therefore excluded from data analysis. Patients assigned with the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) codes of K86 (uncomplicated HT) or K87 (complicated HT) and regularly followed up at a General Outpatient Clinic of Kowloon Central Cluster between 01/01/2013 to 31/12/2013, and had annual blood and urine check-up performed at least once during this period were identified by the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System (CDARS). The diagnosis of HT is based on NICE clinical guideline 127 on clinical management of primary hypertension in adults (2011).7 Patients’ demographics, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (BP), biochemical parameters (including serum fasting sugar (FBS), serum creatinine (Cr), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), urine albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR) and lipid profile), coexisting chronic illnesses stroke (ICPC K89, K90, K91), ischaemic heart disease (IHD, ICPC K74, K75, K76), diabetes mellitus (DM, ICPC T90) were retrieved from the HA’s Clinical Management System (CMS). The most recent parameters were used for analysis if more than one test had been performed during the study period. BP control is defined as BP below 140/90mmHg in non-diabetic hypertensive patients aged under 80 years old and below 150/90 mmHg in people aged 80 years and over.7 For those with concomitant diabetes or CKD (defined as an eGFR < 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2), target BP control is below 130/80mmhg.8 All data were entered and analysed using SPSS (Windows version 16.0; Inc, Chicago [IL], US). Student’s t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used for analysing continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical data. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant. Results 13,558 hypertensive patients were identified from the CMS during the study period, among which 2,787 (20.6%) were excluded (Figure 1). Among the 10,771 patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria, 10,121 (94.0%) were Chinese and 650 (6.0%) were EMGs. Among the 2,787 excluded patients, 144 were EMGs with a proportion (6.9%) comparable to those included into the data analysis (P = 0.14).

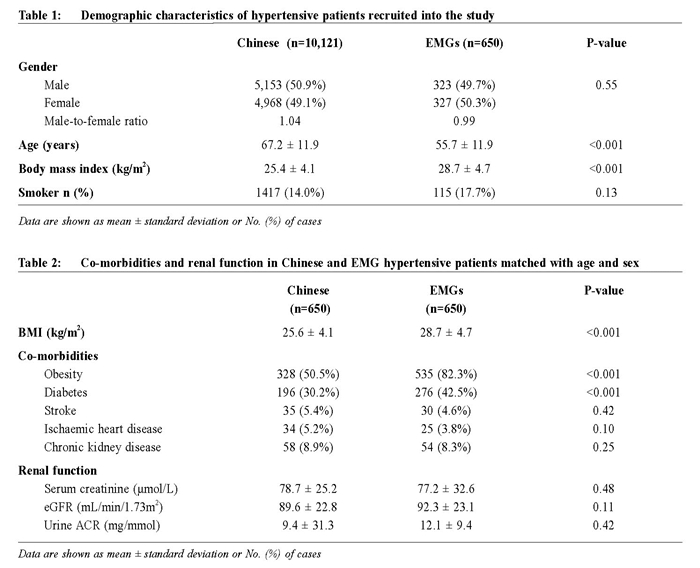

Table 1 summarised the demographic characteristics of hypertensive patients from both Chinese groups and EMGs. No significant differences exist in terms of gender ratio and smoking status. However, EMGs were significantly younger (55.7 ± 11.9 years versus 67.2 ± 11.9 years, P < 0.001) and had much higher BMI (28.7 ± 4.7kg/m2 versus 25.6 ± 4.1kg/m2, P < 0.001).

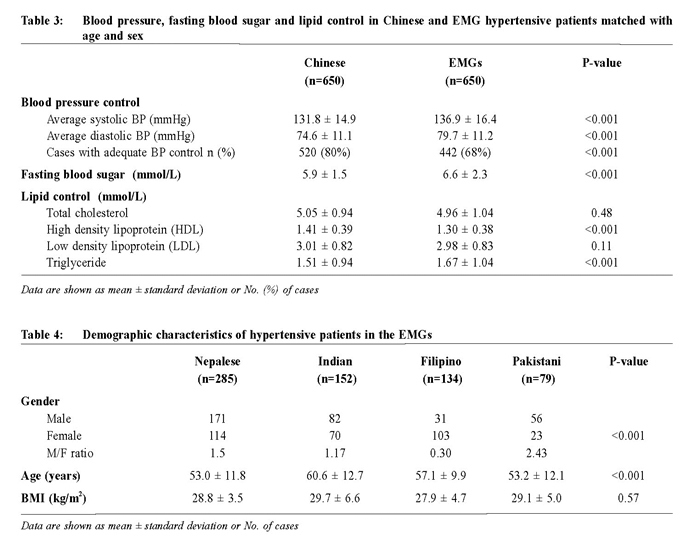

To reduce the confounding effect of age on the study outcome, 650 age -and sex -matched hypertensive patients were randomly selected from the Chinese hypertensive cohort using random numbers generated from a research randomiser (http://www.randomizer.org/form.htm). Table 2 summarised the co-morbidities and renal function in Chinese and EMG hypertensive patients matched with age and sex. A greater proportion of EMGs were obese (82.3% versus 50.5%, P < 0.001) and had DM (42.5% versus 30.2%, P < 0.001). There were no significant differences in the prevalence of other comorbidities or biochemical parameters. Table 3 compared the BP control, FBS level and lipid control in age and gender matched Chinese and EMGs patients. EMGs had higher systolic and diastolic BP (both P < 0.001), and had a much lower proportion with BP adequately controlled (68% versus 80%, P < 0.001). Average FBS level was also higher in EMGs (6.6 ± 2.3mmol/L vs 5.9 ± 1.5mmol/L, P < 0.001). Within lipid profile, high density lipoprotein (HDL) level was lower while triglyceride level higher in EMGs (P < 0.001).

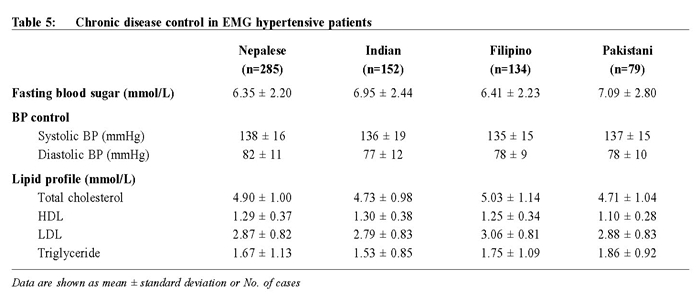

Further studies looking into the demographical characteristics of hypertensive patients in the EMGs showed that most patients were Nepalese (n = 285), followed by Indian (n = 152), Filipino (n = 134) and Pakistani (n = 79) (Table 4). The male to female ratio was higher in the Pakistani and Nepalese groups (P < 0.001). However, the mean age of Nepalese and Pakistani was younger than the Indian and Indonesian group (P < 0.001). /p> Table 5 shows the FBS, BP and lipid control within the EMGs. Since the dissimilar age and gender composition of different EMGs may heavily confound the clinical outcome, direct comparison was not made in these regards. The data showed that Pakistanis had the highest average FBS (7.09 ± 2.80mmol/L), followed by Indians (6.95 ± 2.44mmol/L). Although the average systolic BP was similar among all EMGs, Nepalese hypertensive patients were found to have a comparatively higher average diastolic BP level (82 ± 11mmhg). Pakistanis also had lower HDL (1.10 ± 0.28 mmol/L) and higher triglyceride levels (1.86 ± 0.92mmol/L).

Discussions This is the first local study exploring the management of hypertension in our local EMGs. Our results demonstrated there are ethnic differences in terms of co-morbidity profile, BP control and lipid control. Demographic differences between Chinese and EMG hypertensive patients in terms of age and BMI are consistent with findings from the 2011 Hong Kong census2 and another local study on diabetic patients. 10 It is important to note that hypertensive patients from EMGs of this study were more obese with a much higher BMI than Chinese hypertensive patients. It is well known that obesity prevalence varies substantially between ethnic groups and its estimates differ according to the measurement used (for example, BMI, waist-tohip ratio and waist circumference). Although no data in the literature has directly compared the BMI of Chinese hypertensive patients with the BMI of the South Asian hypertensive patients, studies from Joint Health Survey for England in 2004 looking at the Health of Minority Ethnic Groups in United Kingdom had revealed that the proportion of population with BMI over 30 mg/m2 and waist to hip ratio over 0.95 was much higher in South Asian groups including Indian and Pakistani than in Chinese ethnicities.11 Our results showed that EMGs have higher prevalence of obesity and diabetes, findings that are consistent with previous studies among South Asians.12,13Indeed, South Asians have a much higher prevalence of DM with cardiovascular disease occurring at an earlier age and is associated with higher morbidity and mortality. 14 Therefore, routine screening for diabetes is particularly important in these groups of patients. Intervention strategies including timely referral for ethnical diet and lifestyle modifications to maintain an optimal body weight are strongly advised to prevent the development of diabetes among the EMGs. Overall, our results demonstrated that EMGs have a worse cardiovascular disease risk profile, which again is consistent with previous studies.15 Reasons for this disparity are likely to be multi-factorial. Firstly, their higher prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndrome can as a whole be more challenging to manage. Secondly, EMGs are often at a socioeconomic disadvantage, with greater difficulties accessing medical care.2 Thirdly, language barrier may very often be an issue existing among EMGs, resulting in medical illiteracy. Indeed, our preliminary data have shown that hypertensive patients from the EMGs had a higher default rate (13%) compared with Chinese patients (7%). The high default rate and likely drug non-adherence would further contribute to poor BP control. Lastly, their cultures, religious beliefs and lifestyles may influence on behavior (including physical activity and food choices) and affect health care delivery and management. Therefore, coordinated efforts are needed to overcome these limitations and embark on integrated hypertensive monitoring and surveillance programmes in the EMGs. Particular attention should be paid to the needs of different ethical groups and offer a flexible care package that reflects their physical, psychological, social and cultural needs and upholds their autonomy, dignity, privacy and personal choice. To reduce health disparities between local and EMG patients, comprehensive action plans and strategies should be taken to expand health care access among EMGs. Nowadays, information and interpretation services have been provided across Hong Kong HA clinics and ethnical dietary counseling is also provided in some hospitals. All these will help raise awareness among EMGs and improve their understanding. Limitations of this study Our results may not be generalisable to all of Hong Kong’s EMGs since our study only involved one clinic and have only included those EMGs with regular follow ups and annual assessments. Nevertheless, just as our results have shown, the proportions of EMG in both included and excluded groups were comparable (P = 0.14). We have also compared major epidemiological characteristics including age and gender between those who had regular check-up and those without and found that there was no obvious difference (P = 0.5 and P = 0.66 respectively). Our study may have underestimated the prevalence of co-morbidities in our studied population since these were based upon doctors’ ICPC coding accuracy.

Conclusions EMG is an integral part of our Hong Kong population. Compared with Chinese hypertensive patients, ethnic minority hypertensive patients were much younger but more obese. Deficiencies existed in the comprehensive management of diabetes, particularly in their glycaemic control. Culturally tailored healthcare interventions are therefore required to promote patient education and clinical effectiveness among these groups of patients and improve their health status in the long run. Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere thanks to Dr King Chan for his continuous inspirations and support during this study. I am also grateful to Ms Katherine Chan, statistical officer of Queen Elizabeth Hospital, for her expertise in statistical support in the data analysis. Catherine XR Chen, PhD (Medicine)(HK), MRCP

(UK), FRACGP (Australia), FHKAM (Family Medicine) Department of Family Medicine and General Outpatient Clinics, Kowloon Central Cluster, Hospital Authority. Correspondence to: Dr Catherine XR Chen, Department of Family Medicine & General Outpatient Clinics, Room 807, Block S, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, 30 Gascoigne Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China. References

|

||