|

September 2021,Volume 43, No.3

|

Original Article

|

Survey on family doctorsʼ perception of the District Health Centre (DHC) in Hong KongWill LH Leung 梁樂行,Alvin CY Chan 陳鍾煜,Dicken CC Chan 陳昌俊,Ryan YF Ho 何旭暉,Samuel YS Wong 黃仰山, and The Hong Kong College of Family Physicians 香港家庭醫學學院 HK Pract 2021;43:68-79 Summary

Objective:

To explore family doctors' perception of the

District Health Centre (DHC)

Keywords: Primary healthcare; District Health Centre; family doctors 摘要

目標:

探討家庭醫生對地區康健中心(DHC)的認知

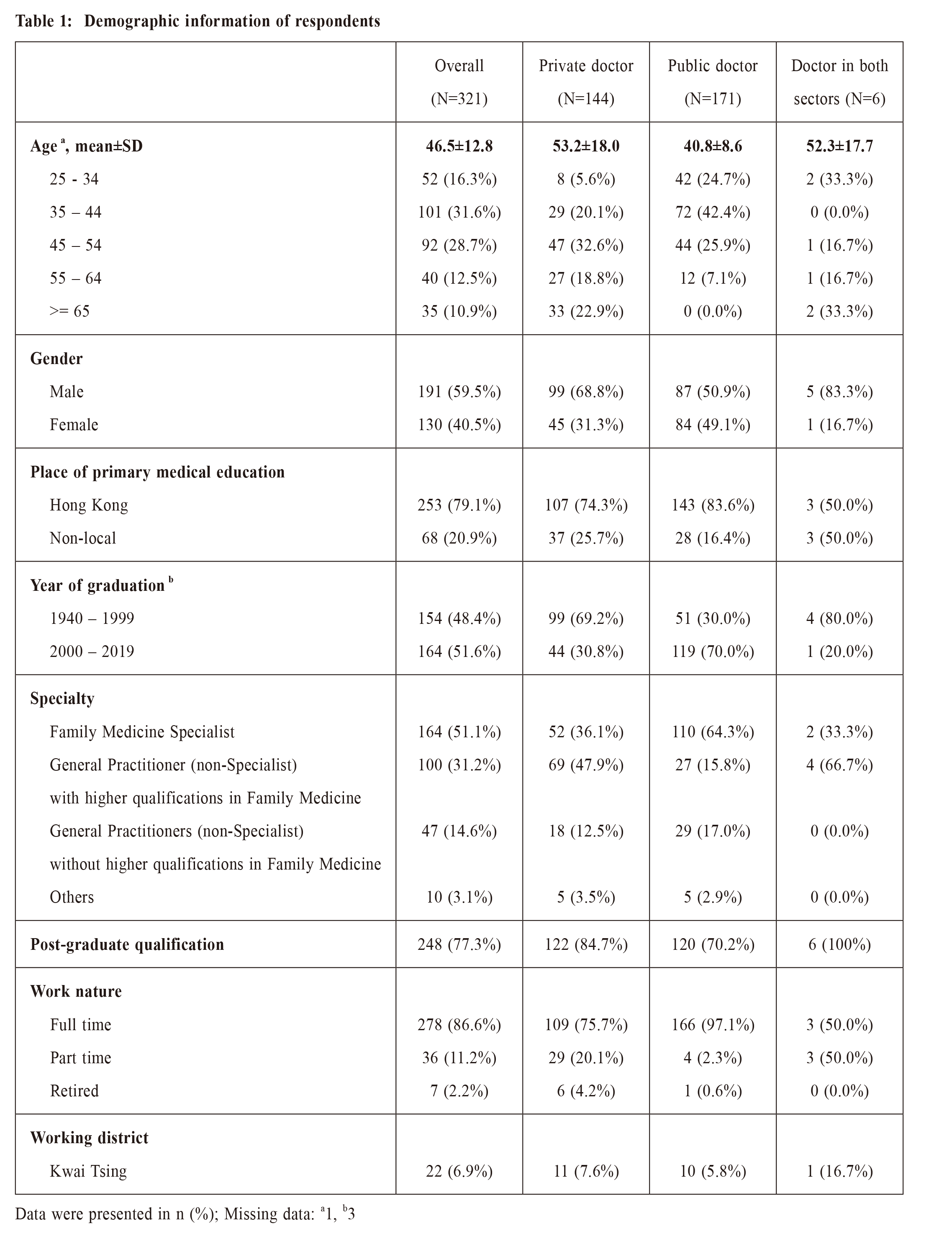

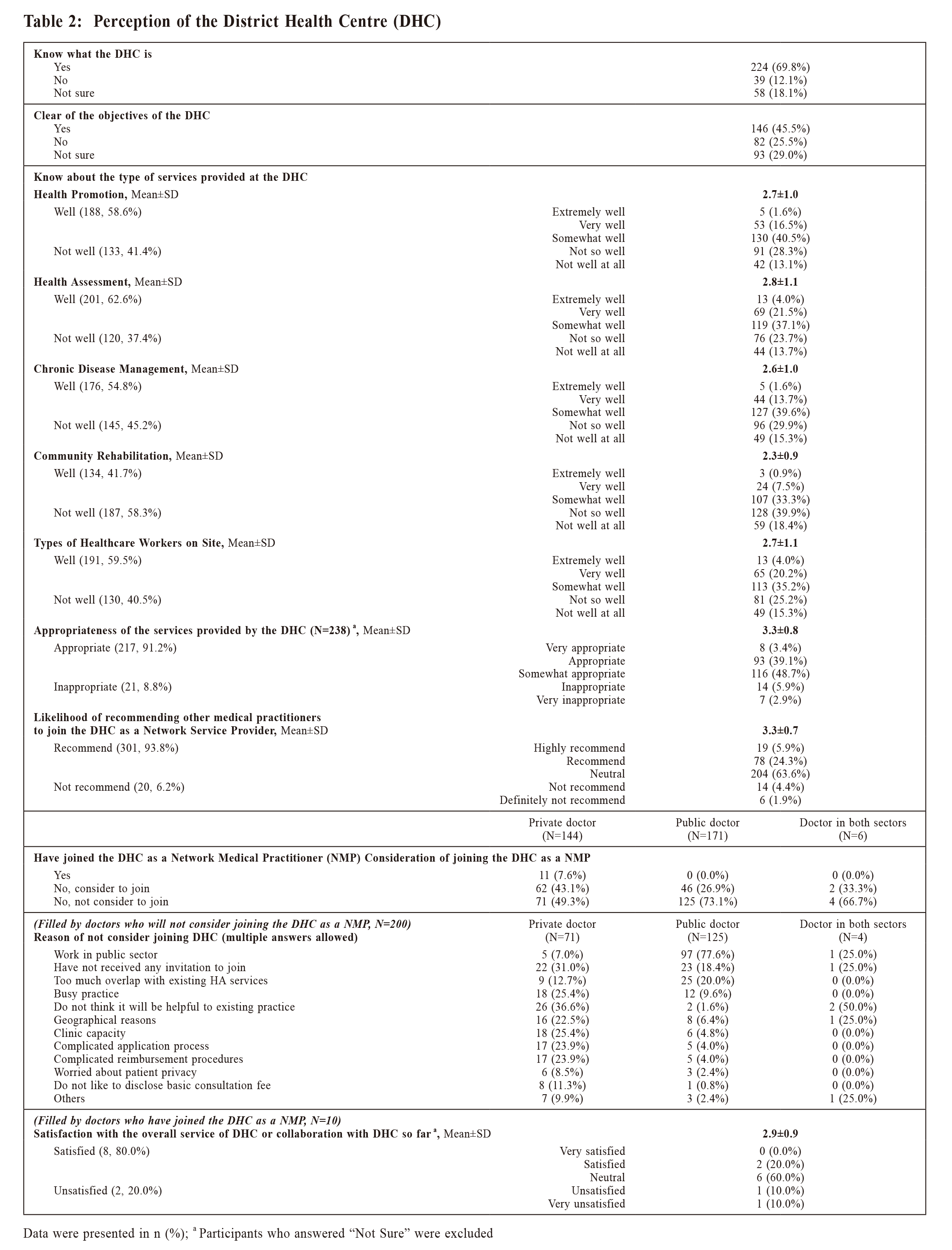

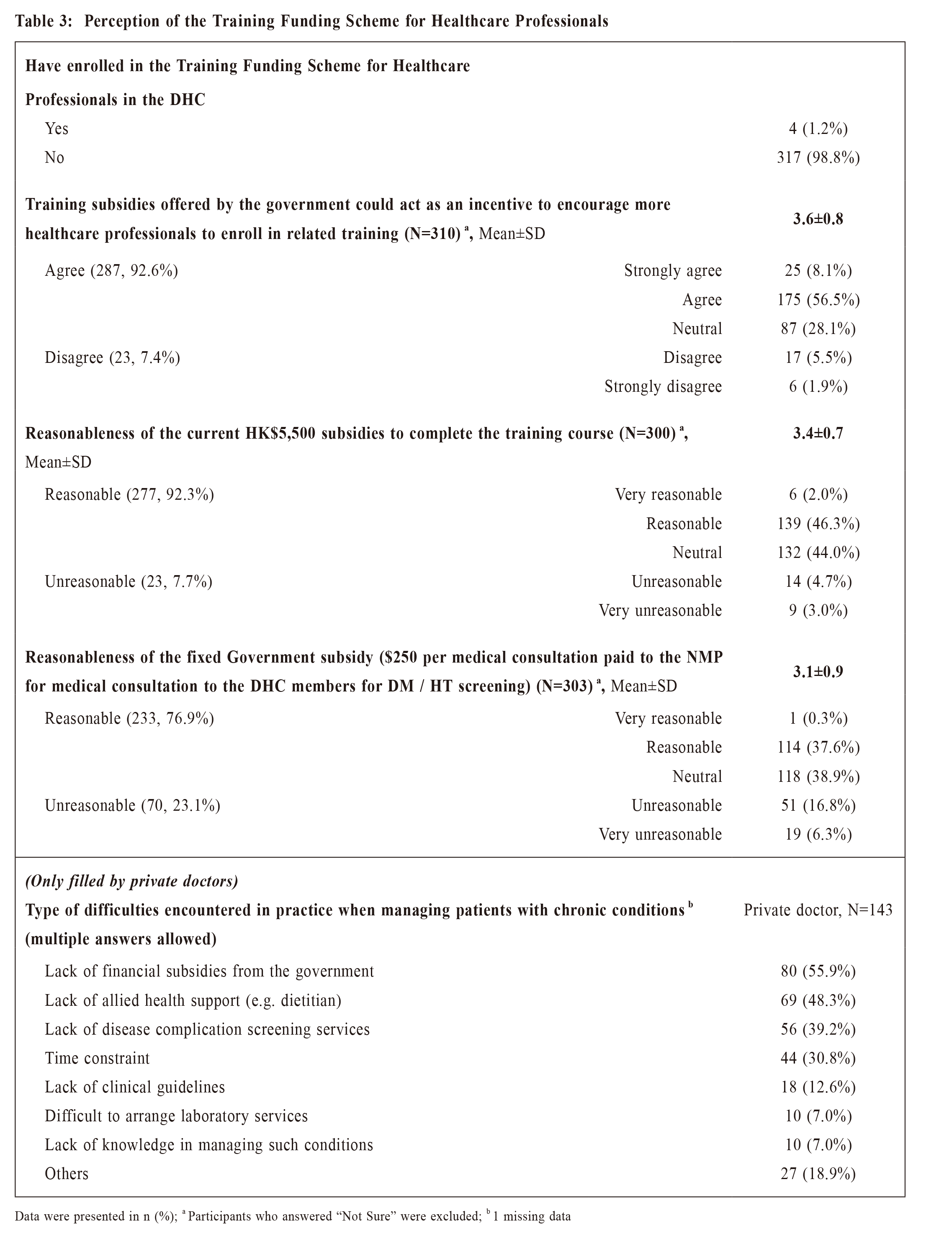

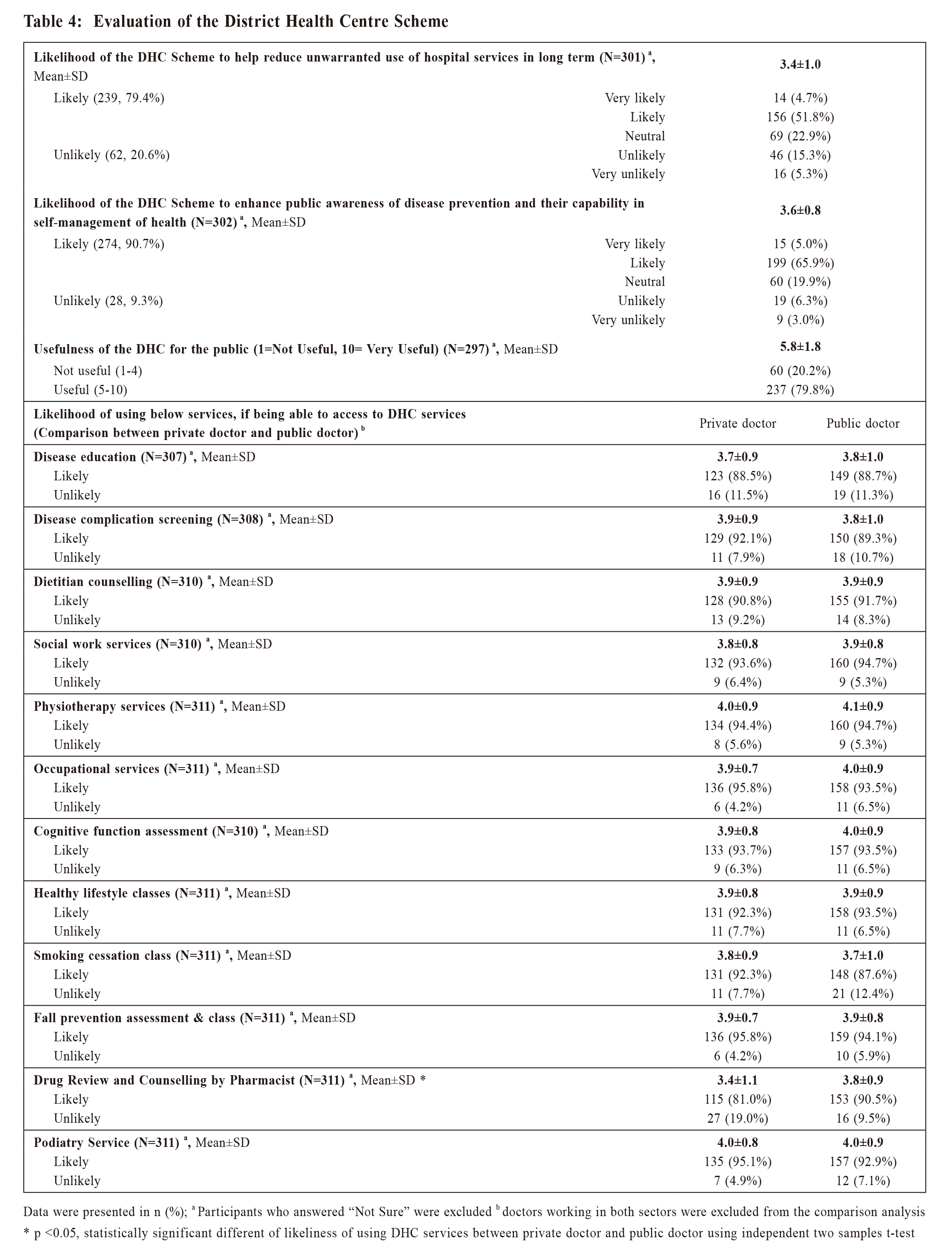

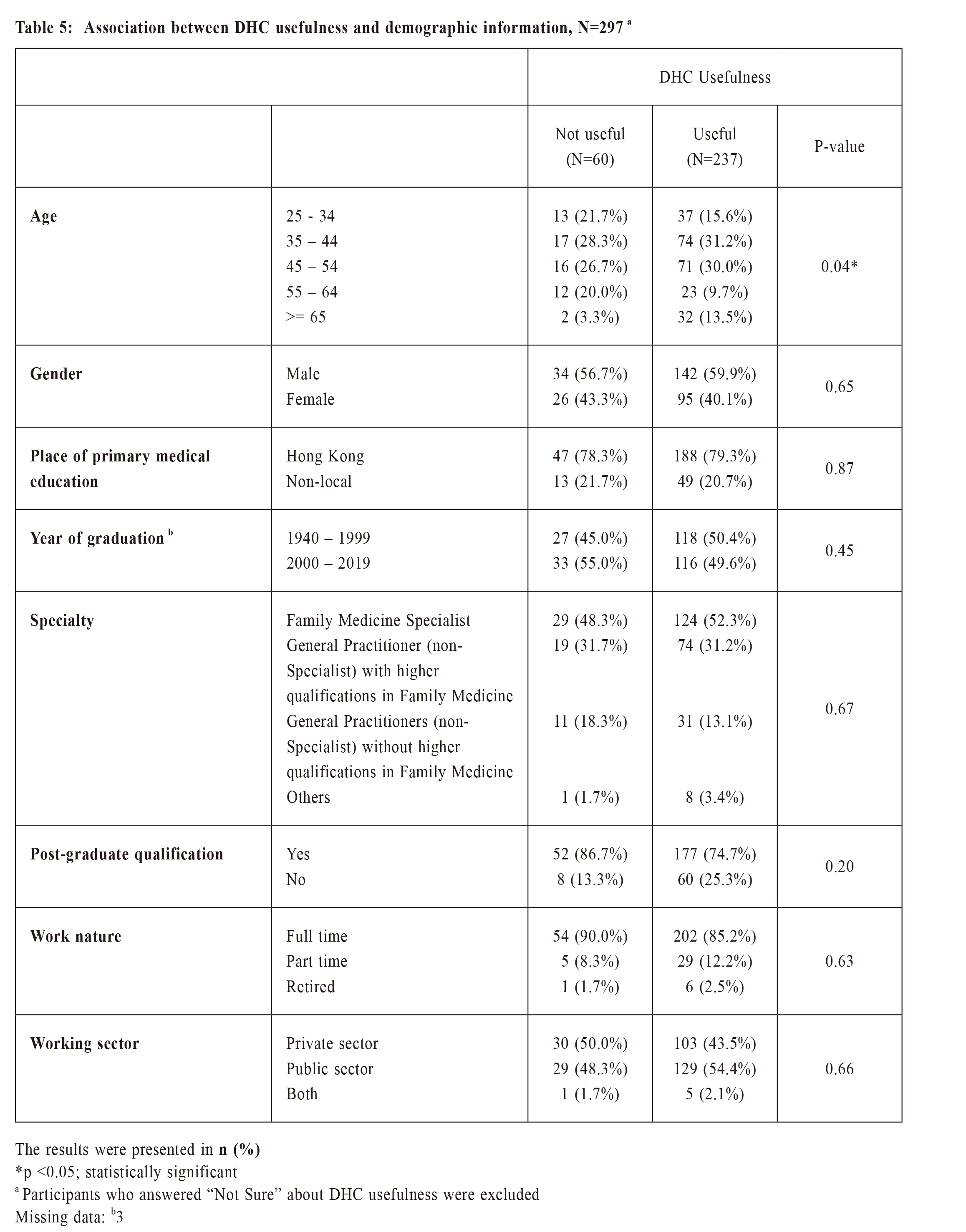

主要詞彙: 基層醫療;地區康健中心;家庭醫生 IntroductionPrimary care serves an important role in improving health of a population, prevention of illness and death, and distribution of equitable health within and across populations. 1 Primary care has a greater focus on prevention in reducing unnecessary specialist care.2 Primary health care is a whole-of-society approach to health and well-being centred on the needs and preferences of individuals, families and communities. It addresses the broader determinants of health and focuses on the comprehensive and interrelated aspects of physical, mental and social health and wellbeing. Primary health care has been proven to be a highly effective and efficient way to address the main causes and risks of poor health and well-being. Stronger primary health care is essential to achieving the health-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and universal health coverage.3 District Health Centre (DHC) is an initiative by the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) to strengthen district-based primary healthcare services in Hong Kong. The mission and vision of District Health Centres are for people to become engaged with medical professionals in the community providing quality care with the ultimate goal to improving their health and well-being. This leads to a reduction in the need for secondary and tertiary care, hospitalisation and generates wider social benefits. Through a multidisciplinary care approach, DHC provides a variety of primary healthcare services, including health promotion, disease prevention, chronic disease management and community rehabilitation. The first DHC in Hong Kong officially opened in September 2019 in Kwai Tsing District. DHC consists of a core centre and several satellite centres. DHC operator purchases private healthcare services from the district forming a DHC network. The comprehensive network includes medical consultation, Chinese medicine consultation, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, dietetics, optometry, podiatry and speech therapy. The Government offers subsidies for the provision of DHC network services. The DHC Operator contracts separately with the network service providers. Care managers and members of the primary healthcare team at the DHC establish a Partnership with Family Doctors (FDs) to complement the services offered by them. The team aims at assisting FDs in the monitoring and follow-up on individual self-managing health plans as well as coordinating the supportive ancillary services required to provide holistic and comprehensive care to patients Management of chronic diseases is fundamentally different from acute care, featured by opportunistic case finding for assessment of risk factors, early detection of disease and high risk status; a combination of pharmacological and psychosocial interventions in a stepped-care fashion; and long-term follow-up with regular monitoring and promotion of adherence to treatment.4 A systematic review revealed that multifaceted professional and organisational interventions that facilitate structured and regular review of patients were effective in improving the process of diabetic care. The addition of patient education to these interventions and the enhancement of the role of nurses in diabetes care led to improvements in patient outcomes and the process of care.5 The role of primary care teams in chronic disease management had been described in literature as multidisciplinary care teams, often including nurses and pharmacists, with clinical and behavioural skills to ensure that critical elements of care that doctors may not have the training or time to do well are competently performed.6 Community health worker participation improved chronic disease control parameters from a study on electronic health records of chronic disease patients.7 A study involving ten health centres in diabetic care revealed that both clinical process indicators and health outcome indicators improved significantly more in the intervention group than in the control group, from systems-based approaches that included patients' education and self-management support.8 In Singapore, primary care networks (PCN) were piloted in 2012 and scaled up in 2018, in encouraging private General Practice (GP) clinics to organise themselves into networks to achieve economies of scale and optimise resources to deliver more holistic care in a team-based care model. Under the PCN, patients will receive care through a multidisciplinary team including doctors, nurses, ancillary service and primary care coordinators for more effective management of their chronic conditions. The PCN scheme is part of the strategic shift to move care beyond the hospital to the community, so that patients can receive effective care closer to home.9 A systematic review of literature on the effects of organisational changes to primary care in Canada on health system performance outcomes revealed moderate quality evidence that interdisciplinary team-based models in primary care led to reductions in emergency department use. The review also found evidence that team-based models led to certain improvements in the processes of care as measured by the delivery of screening and prevention services and chronic disease management.10 FDs are serving a key role in primary healthcare team in delivering a patient-centred whole-person care for a family. In order to explore FDs’ understanding of DHC and to collect opinion from FDs to enable DHC and the primary healthcare team to fulfil her mission and vision, the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians (HKCFP) conducted an online survey on “Family Doctors' Perception of the District Health Centre in Hong Kong” in January 2021 MethodsHKCFP members were invited to complete an online survey. The survey was constructed from a group of family doctors including academics, frontline family doctors and researchers in primary care. The questionnaire was designed based on a literature review of primary care providers’ perception on the role of community health centres. An expert panel then evaluated the contents of the questions to ensure the objectives of the study were covered in the questionnaire. Use of mutually exclusive multiple-choice questions, rating scale and open-ended questions produced different types of responses, to gather information about knowledge, preference, attitude and behavior of respondents on various areas of DHC. The structured questionnaire (Appendix 1) comprised of 35 questions. Responses were set at a 5-point Likert scale and were scored on a scale of 1 to 5. The coding score was not applied to “Not sure” and missing response. Individual response was further dichotomised into a binary variable using a cutoff of 3, to distinguish positive / neutral and negative response. For usefulness of the DHC for the public, the item was to be rated with a scale ranged from 1-10, where a score of 1-4 was regarded as “Not Useful”, while 5-10 was regarded as “Useful”. The first part consisted of closed-ended questions to assess the background knowledge of respondents on DHC. The second part assessed respondents’ willingness to join DHC as a Network Medical Practitioner (NMP) and likelihood to recommend other medical practitioners to join DHC as a NMP. The reason for those who responded with the answer of “not considering” to join as NMP were explored in detail. The third part explored respondents’ opinions on DHC Training Funding Scheme for healthcare professionals and relevant incentives for training. The fourth part collected opinions from respondents regarding usefulness of DHC in reducing unwarranted use of hospital services in the long term and enhancing public awareness of disease prevention and their capability in self-management of health. The fifth part of the survey asked respondents on accessibility and applicability of DHC services and included an open-ended question for respondents to offer suggestions on the DHC scheme. The last part contained 8 questions on demographic parameters of the respondents. Invitation of the survey was sent by e-mail and HKCFP Newsletter to participants on 6 January 2021 Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the characteristics of the respondents. Continuous variables were presented as means (standard deviation) and categorical variables as count (percentage). Pearson’s Chi-squared test was performed to evaluate whether DHC usefulness differed by respondents’ demographics. Respondents were stratified by age, gender, place of primary medical education, year of graduation, specialty, post-graduate qualification, work nature (full time, part time, retired), and practice sector (public vs private) in analysing respondents’ likeliness of using DHC service, and the association between DHC usefulness and demographics. The likelihood of using DHC service between public and private FDs were compared by independent two samples t-test. All significance tests were two-tailed and those with a P value of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was executed using statistical package IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26). Ethics approval was obtained from the Survey and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee of The Chinese University of Hong Kong (Reference No. SBRE-20- 302). Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist for cross-sectional studies was used in the drafting of this manuscript. ResultDemographics of respondentsOf the 1706 HKCFP members invited to complete the survey, 321 (18.8%) provided a complete and valid response to the survey. Of the 321 respondents, 164 (51.1%) were Family Medicine (FM) Specialists and 278 (86.6%) were practicing full-time. A total of 144 (44.9%) worked in the private sector and 71 (22.1%) worked as solo private practice FDs. Twenty-two (6.9%) worked in Kwai Tsing District, where the DHC is running in Hong Kong at the time of the survey (Table 1). Perception of DHCMore than half of the doctor respondents knew what DHC was (69.8%), while less than half of the doctors knew the objectives of the DHC (45.5%) (Table 2). Upon in-depth questioning of all items regarding knowledge on the type of services provided by the DHC, the mean scores ranged from 2.3 to 2.8 (1=not very well at all; 5=extremely well). Moreover, respondents viewed that the services provided by the DHC were appropriate with a mean score of 3.3±0.8 SD (1= Very inappropriate; 5=Very appropriate) and they would recommend other medical practitioners to join the DHC as a NMP (a mean score of 3.3±0.7 SD with 1=definitely not recommend; 5= highly recommend). Experience of working with the DHCFor doctors who joined as a NMP (N=11), 8 rated the experience as “satisfied or neutral”; two were unsatisfied; one was not sure about the overall service of DHC or collaboration with DHC so far (Table 2). Among the 310 doctors who have not joined DHC, 110 doctors have considered to join but 200 doctors have not considered joining as network doctor. The most common reasons for not joining the DHC included “the respondents working in public sector” (51.5%); “they have not received any invitation to join” (23%) and “there was too much overlap with the existing HA services” (17%). Further analysis was conducted among private doctors who have not considered joining as network doctors. The most common reasons for not considering joining as network doctor included “do not think it will be helpful to existing practice (36.6%)”, “have not received any invitation to join (31%)”, “busy practice (25.4%)”, “clinic capacity (25.4%)”, “complicated application process/complicated reimbursement procedures (23.9%)”. Training for DHC healthcare professionalsOnly four out of the 321 doctors were noted to be enrolled in the Training Funding Scheme (Table 3); 1 had joined DHC; 2 would consider to join DHC; 1 would not consider to join DHC. The main reasons of not enrolling in the Training Funding Scheme were that they were not NMP (38.5%) or they were FM Fellows (30.9%). Most doctors (92.6%) agreed training subsidies offered by the Government could act as an incentive to encourage more healthcare professionals to enroll in related training to support primary healthcare development in Hong Kong, in accordance with a mean score of 3.6±0.8 SD (1=Strongly disagree; 5=Strongly agree). Monetary incentives could encourage more doctors to join the training and the amount of subsidies $5,500 was regarded as reasonable (mean score 3.4±0.7 SD). For doctors who thought that the current subsidies was unreasonable or neutral, 44 out of 155 viewed the amount shall be raised to $10,000 or above; 45 thought the amount of subsidies should cover at least 40% of the training course fee. Support for doctors by DHCFor private doctors, the main difficulty encountered in practice when managing patients with chronic conditions was the lack of financial subsidies from the government (55.9%), followed by the lack of allied health support (48.3%) (Table 3). The majority of respondents (76.9%) viewed the financial subsidy of the fixed amount $250 per consultation paid to the NMP for diabetes mellitus (DM) or hypertension (HT) screening as being a reasonable amount (mean score 3.1±0.9 SD). Usefulness of DHCMost doctors (79.8%) rated DHC as useful (5- 10) with a mean score of 5.8±1.8 SD (1= Not useful at all; 10= Very useful) (Table 4). Age of the doctor was found to be associated with DHC usefulness rating. Doctors aged 65 or above tend to think DHC was useful for the public. No trend effect in age was observed. Besides age, no statistically significant association was found between DHC usefulness and other demographic variables of the respondents (Table 5). For doctors who rated 5-10 on DHC usefulness, they thought DHC could benefit the public based on the following reasons: (1) DHC provides comprehensive care or higher quality services to patients, and provides an alternative option for the public; (2) Increase access to allied health service.

Utilisation of DHC Out of the 317 doctors, 85.8% - 95% of the doctors rated “likely” to all items regarding the likelihood of using the DHC or the DHC Express services (Table 4). More public doctors, as compared with private doctors, would be more likely to use drug review and counselling by Pharmacist (mean score of 3.8±0.9 SD vs 3.4±1.1 SD, p=0.001). In addition, both public doctors and private doctors reported a high likelihood to use physiotherapy services at DHC (mean score of 4.1±0.9 SD vs 4.0±0.9 SD)

Discussion

|

|