|

December 2021,Volume 43, No.4

|

Case Report

|

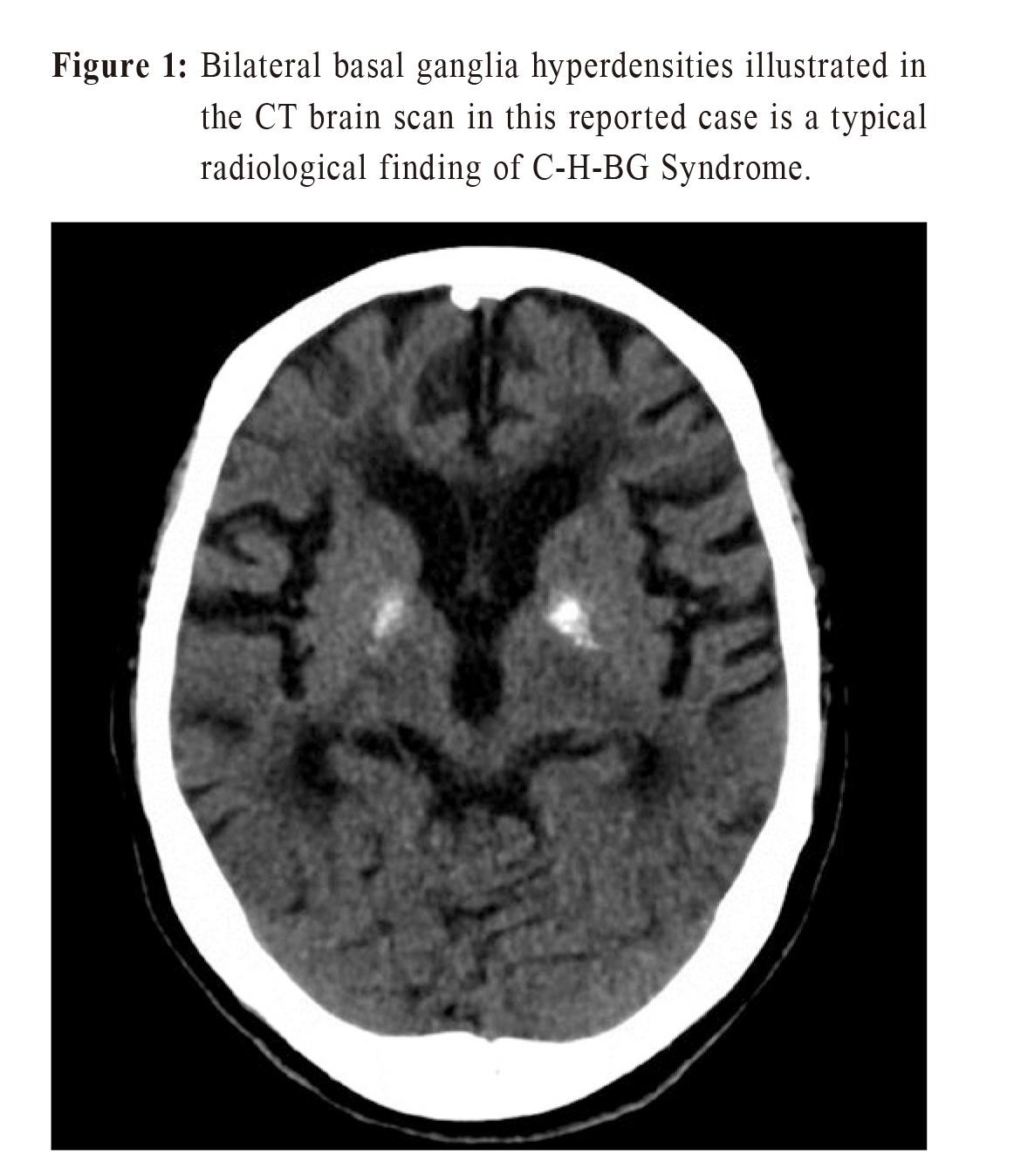

Hyperglycaemia presented with Chorea: a case report from primary careAnnie KY Or 柯嘉茵,Catherine XR Chen 陳曉瑞 HK Pract 2021;43:120-123 SummaryChorea is an involuntary hyperkinetic movement disorder characterised by rapid and unpredictable contractions over mainly distal limbs, the face and the trunk. We report on the case of an 89-year-old lady encountered in the General Outpatient Clinic, who presented with choreiform movements due to her hyperglycaemia. She was admitted into hospital and subsequently recovered completely after correction of her hyperglycaemia. There was also an associated radiological finding of hyperdensities in her bilateral basal ganglia which is now regarded as the Chorea Hyperglycaemia Basal Ganglia Syndrome. Although the pathophysiology of this syndrome is still unknown, it is vital for family physicians to be familiarised with this condition because it is one of the rare and reversible complications of uncontrolled diabetes; to better ensure an early diagnosis, appropriate management and good patient outcome. 摘要舞蹈症是一種不自主的運動過度性障礙,其主要特徵是四肢,面部和軀幹快速且不可預測的肌肉收縮。我們報告了一例在普通科門診就診的糖尿病患者,她因過高的血糖而出現了舞蹈症。轉介入院後腦部電腦掃描檢查顯示雙邊基底核有高密度病灶,診斷為非酮症高血糖偏側舞蹈症(C-H-BG)。高血糖得到控制後,舞蹈症也完全康復。儘管該綜合症非常罕見, 而且其病理機制尚不清楚,但對於家庭醫生而言,能及早確診C-H-BG尤其重要,因為及時的治療可以將舞蹈症完全根治,逆轉因高血糖而帶來的併發症。 IntroductionChorea is a rare neurological manifestation with many different causes, the most well-known is Huntington’s Disease (HD) which is an autosomal-dominant hereditary disease. Among the acquired causes which lead to more acute onset of chorea, a large proportions are caused by central nervous vascular lesions (40%); other causes, such as autoimmune, inflammatory particularly Sydenham chorea, metabolic, infectious agents, toxins, drugs or structural lesion in the basal ganglia, should also be considered. This present case illustrates the need to be aware of hyperglycaemia as a cause of hemiballism/hemichorea, which is the hallmark of the Chorea Hyperglycaemia Basal Ganglia syndrome (C-H-BG ). Case PresentationMadam CSK is an 89-year-old lady. She is a non-smoker and non-drinker. She has regularly been followed up at a General Out-patient Clinic (GOPC) of the Hospital Authority of Hong Kong for management of hypertension, Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and ischemic heart disease. HistoryShe was seen on 7/7/2017 as a routine follow-up (FU) for her chronic diseases. Her medication list included Aspirin, Pantoprazole, Gliclazide, Metformin, Lisinopril, Nifedipine retard and Simvastatin. Latest diabetic complications screening performed on 30/6/2017 showed her HbA1c level was 7.1%, creatinine level was 105µmol/L and lipid profile was normal. There were no diabetic microvascular complications. Her following scheduled FU was 27/11/2017 but she defaulted the FU when she did not turn up after that. Madam CSK then attended the above mentioned clinic on 2/2/2018 for episodic care. Clinical examinationShe complained of subacute onset of involuntary movements over her left upper limb in July 2018 for two days. There was no concomitant headache, dizziness, slurring of speech, dysphasia, blurring vision or hearing problem. She did not have any limb weakness or numbness, nor any limb rigidity or tremor. There was no fever or any coryzal symptoms suggestive of infective causes either. She did not have any head injury earlier, nor had she taken any over-the-counter drug lately. There was no family history of hereditary problems like HD or other neurodegenerative diseases. No decline in her cognitive function or behavioural changes were noted either. On physical examination, her general condition was stable with a high blood pressure reading of 160/85 mmHg. She was afebrile, conscious and alert, and was oriented in time, place and person. Neurological examination yielded no grossly remarkable finding, except the subtle involuntary movement of a choreo-ballismus nature with her left entire upper limb. There was no dystonia or rigidity. The sensation and power of her four limbs were normal. Initial impression was chorea of subacute onset over her left upper limb from a suspected vascular cause. The patient was therefore urgently referred to the Accident and Emergency Department (AED) for further management. Upon admission to AED, the patient was noted to be mildly dehydrated with a high spot glucose level of 20.6 mmol/L and was given an injection of a short acting insulin. The patient was then admitted to the medical ward for further work-up. Blood tests revealed that her creatinine level had shot up to 203µmol/L from baseline of 105µmol/L 8 months previously. Otherwise, the complete blood picture, electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, liver function, thyroid function, effective serum osmolality, bicarbonate and ammonia level were all normal. Subsequent findings and final diagnosisComputed Tomography (CT) brain was performed and there were hyperdensities in her bilateral basal ganglia region, age-related cerebral atrophic changes and periventricular chronic ischemic changes (Figure 1). She was later diagnosed to have the C-H-BG syndrome.

The subsequent blood testing showed that her hemoglobin A1c level (HbA1c) increased from 7.1% on 30/6/2017 to 10.0% on 3/2/2018 in the 8 months. Although Madam CSK was reported to have good drug compliance, she had defaulted regular follow-up and the dose of her oral hyperglycemic agent had also been decreased in a previous visit, both of which could have contributed to the worsening of her HbA1c control. After admission, her glycemic control was modified by a new drug regime and titrated insulin dose. The chorea movements subsided after better control of serum blood glucose level in hospital. CT brain was repeated on 6/2/2018, which revealed no interval changes. She was then discharged home without any further neurological sequelae. She continued her FU in GOPC for further management of her DM with quarterly monitoring of her blood HbA1c. Subsequent investigations done 3 months later showed that her HbA1c showed a decreasing trend.

Discussion

|

|