|

September 2019,Volume 41, No.3

|

Update Article

|

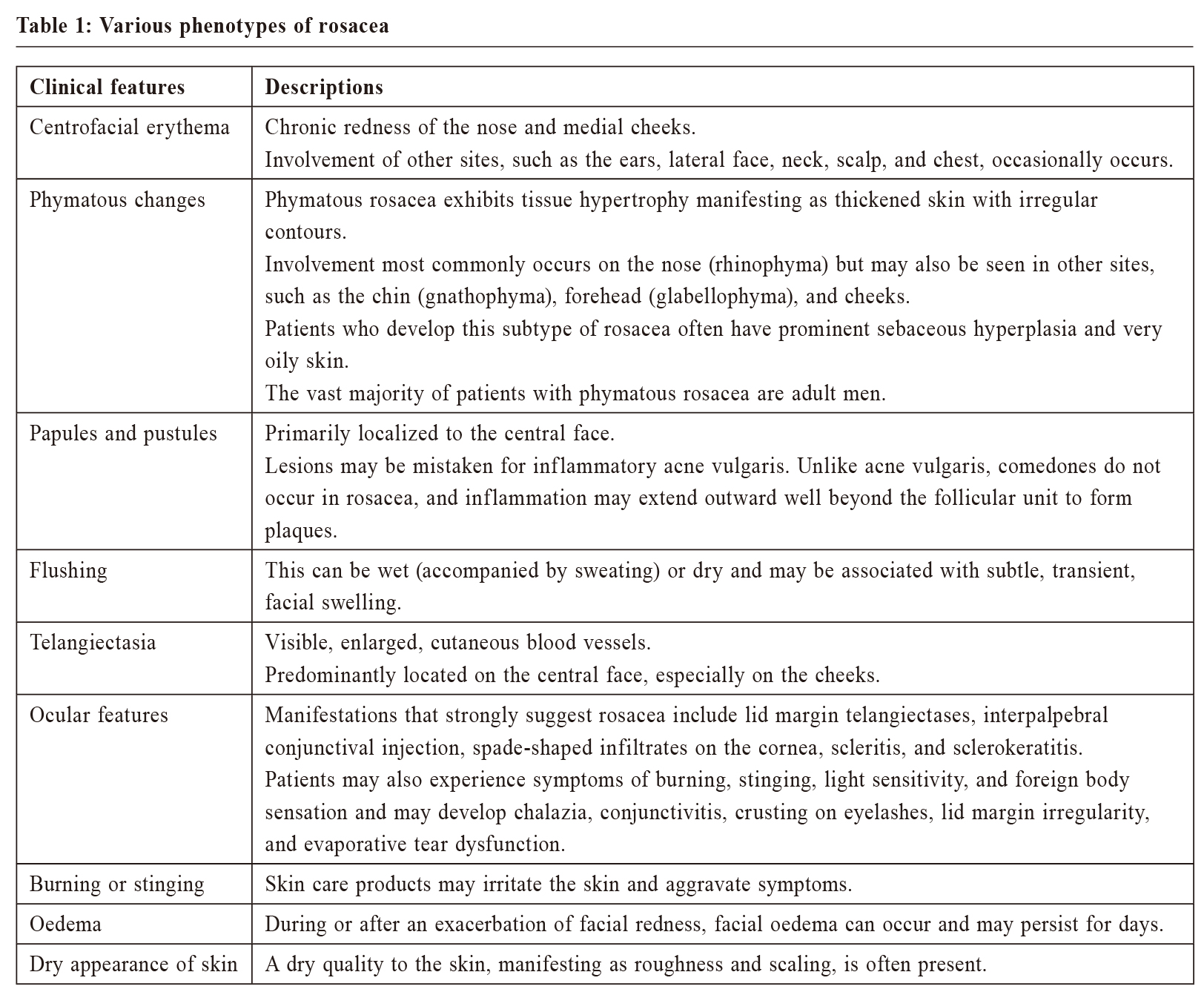

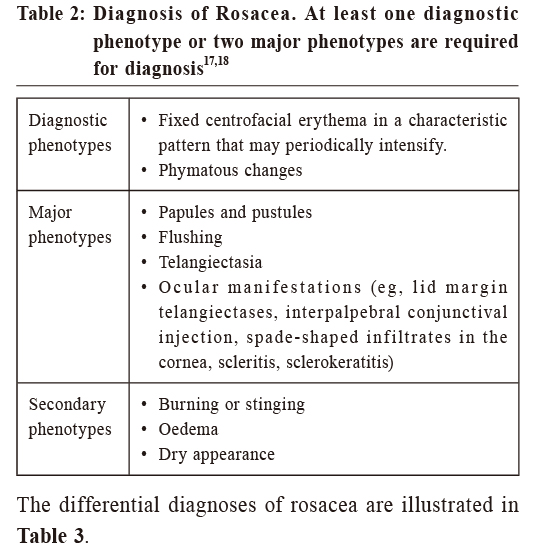

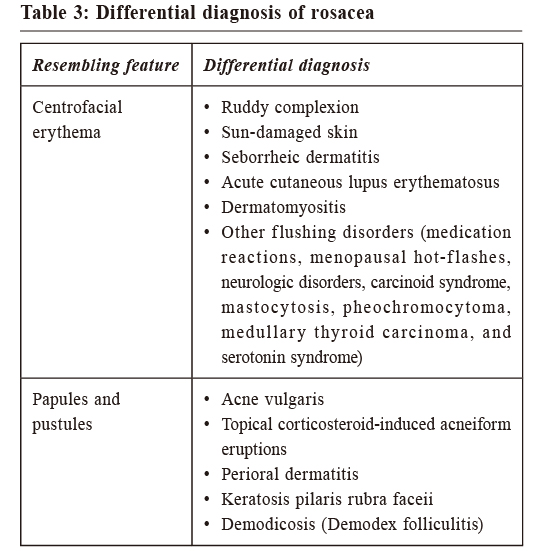

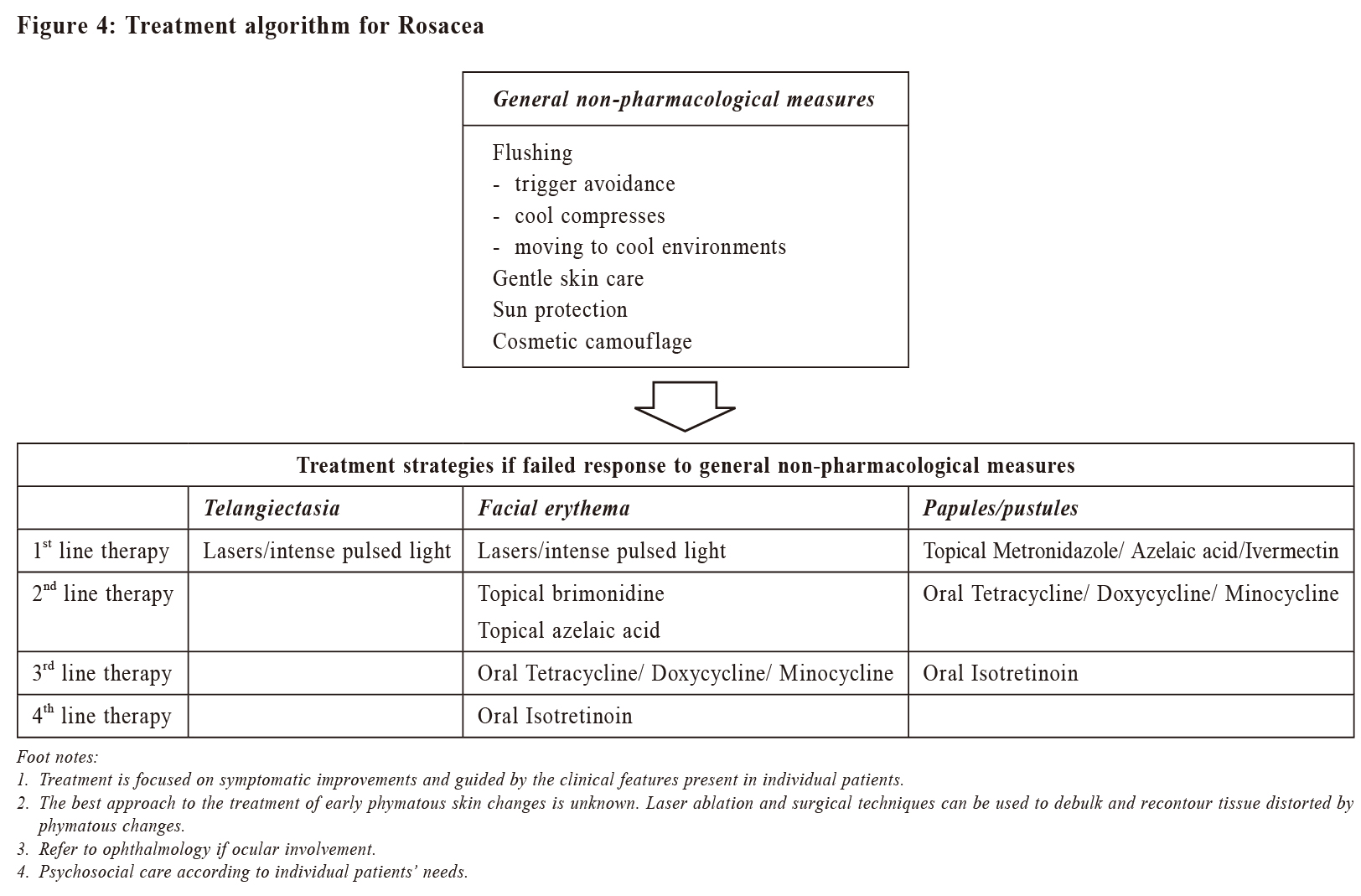

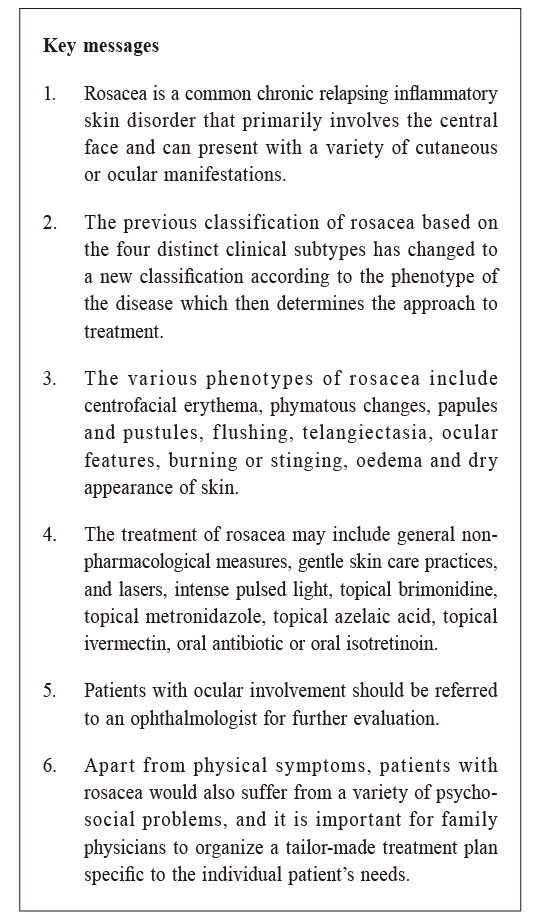

An update article on rosacea for the family physicianWai-man Yeung 楊偉民,David CK Luk 陸志剛,David VK Chao 周偉強 HK Pract 2019;41:77-84 Summary Rosacea is a common problem in family medicine. The aim of this article is to provide an update on this topic with practical information to family physicians, including clinical presentations, diagnosis, classification and treatment of rosacea for the family physician. 摘要 玫瑰痤瘡(亦稱酒渣鼻)是家庭醫學中常見的問題。本文旨在為家庭醫學科醫生提供這疾病最新而實用的資訊。其中包括玫瑰痤瘡的臨床徵狀、診斷、分類和治療。 IntroductionRosacea is a common chronic relapsing inflammatory skin disorder that primarily involves the central face, and can present with a variety of cutaneous or ocular manifestations. The aim of this article is to provide an update on this topic with practical information for the family physician, and not to make a full review. The previous classification of rosacea based on the four distinct clinical subtypes has changed to a new classification according to the phenotype of the disease which then determines the approach to treatment. Apart from physical symptoms, patients with rosacea can also suffer from a variety of psycho-social problems. Therefore, it is important for family physicians to organize a tailor-made treatment plan specific to the individual patient’s needs. EpidemiologyRosacea occurs in people of all ethnic backgrounds but is most frequently observed in individuals with lightly pigmented skin. People of Celtic and Northern European origin appear to have the greatest risk for this disorder.1,2 The prevalence of rosacea is difficult to assess due to its variable clinical manifestations and the wide variety of other skin disorders that exhibit similar clinical features. The estimates of the prevalence of rosacea in fair-skinned populations range from 1 to 10 percent.1,3,4 Rosacea is often seen in our locality, though as yet there is no published data on its prevalence in Hong Kong. It is known that rosacea primarily occurs in adults over the age of 30 but can also occasionally occur in adolescents. In this younger age group it can often be mistaken for acne vulgaris. Rosacea rarely makes an appearance in young children.5,6,7 This disorder occurs more frequently in women than in men1,8, except for patients with phymatous skin changes which mainly affect adult males. Obesity and histories of smoking, and an increased alcohol consumption are possible risk factors for rosacea in women.9,10,11 PathogenesisThe pathogenesis of rosacea is poorly understood.12,13 The proposed contributing factors include abnormalities in the innate immune system, inflammatory reactions to cutaneous microorganisms (e.g. Demodex, Bacillus olenorium), ultraviolet radiation exposure, vascular hyper-reactivity and genetics. The role of gastrointestinal infection caused by Helicobacter pylori is controversial.14,15 ClassificationIn 2002, the National Rosacea Society in the United States of America assembled an expert committee to develop a standard classification system for rosacea. The classification was previously based on four distinct subtypes of rosacea (erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, and ocular rosacea).16 Since then, the increasing knowledge on the pathophysiology of rosacea has favored the view of a multivariate disease process with multiple clinical manifestations rather than distinct subtypes of disease.17 In 2017, following the recommendations from the Global ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) Panel supporting the use of “phenotype-based”, rather than a “subtype-based” approach to the diagnosis and classification of rosacea, the National Rosacea Society expert committee released an update supporting a similar approach.17,18 The phenotype-based approach describes the individual clinical features of rosacea and divides them into diagnostic, major, and secondary (or minor) features/phenotypes. Clinical featuresThe various phenotypes of rosacea are listed in Table 1. Some examples of the different phenotypes are illustrated in Figures 1 to 3. It is important to recognise these features as they are essential for diagnosis. Clinical assessment of the patient is usually sufficient for the diagnosis of rosacea. The diagnosis can be made based upon an assessment of the diagnostic, major, and minor phenotypes (Table 2). Multiple factors have anecdotally been associated with the exacerbations of cutaneous signs and symptoms of rosacea, including exposure to extremes of temperature, sun exposure, hot beverages, spicy foods, alcohol, exercise, irritation from topical products, psychologic feelings (especially anger, rage, and embarrassment), certain drugs (such as nicotinic acid and vasodilators) and skin barrier disruption. In the past, phymatous skin changes in rosacea were perceived by the lay public to be a consequence of heavy alcohol consumption. However, definitive evidence in support of an association between alcohol and increased risk for phymatous skin changes is lacking.19 Skin biopsies are rarely indicated as the histopathologic findings may be non-specific, but can be useful in cases in which another disorder with specific histopathologic findings is suspected or for supporting a diagnosis of granulomatous rosacea. Serologic studies are not useful for confirming the diagnosis. Ocular involvement may present independently or in association with cutaneous manifestations of the disease. Patients who have ocular symptoms or visible signs suggestive of ocular involvement should be referred to ophthalmologists for further evaluation. A variety of other skin conditions may present with clinical features that resemble rosacea.     TreatmentMany patients with rosacea seek treatment due to their concern over their physical appearances. As there is no specific cure for rosacea, treatment is focused on symptomatic improvements. The approach to treatment is guided by the clinical features present in an individual patient. Given the common presence of multiple features, combination therapy may be necessary to achieve satisfactory control of their condition.20 General measuresGeneral non-pharmacological measures may be useful and these include avoidance of triggers of flushing (please refer to the 2nd paragraph of Clinical features and diagnosis), gentle skin care, sun protection, and the use of cosmetic camouflage. Patients can be advised to keep a diary of flushing episodes and potential associated factors to identify and avoid pertinent triggers. Practical measures to reduce flushing after their encounters with stimuli, such as applying cool compresses and moving to cool environments, may be helpful. Gentle skin care practices may help to reduce symptoms. Emollients help repair and maintain cutaneous barrier function and may be useful in rosacea.21,22 Despite their sensitive skin, patients should cleanse their face at least once daily. Patients should be instructed to cleanse their skin gently with lukewarm water, to wash with their fingers, and to avoid harsh mechanical scrubbing.23,24 Non-soap cleansers with synthetic detergents (e.g. beauty bars, mild cleansing bars, many liquid facial cleansers) are usually better tolerated than traditional soaps. The alkaline nature of the latter may raise the pH of the skin and impair its barrier function. 25 In contrast, synthetic detergent cleansers typically have a pH more closely approximates the normal pH of the skin (skin pH = 4.0 to 6.5). Manual exfoliation with rough sponges or cloths should be avoided. Skin care products in the form of foams, powders, or creams are generally better tolerated than alcohol-based gels and thin lotions.24 In addition, using cosmetics which could be easily removed to avoid the need for harsh cleansing is advocated.24 Avoidance of irritating topical products such as toners, astringents, chemical exfoliating agents (e.g. alpha hydroxy acids) are advisable. Specific agentsIf general measures fail, facial erythema, flushing and telangiectasia can be improved with the use of lasers, intense pulsed light, or pharmacologic agents. Light-based modalities do not cure rosacea, and periodic treatments to maintain improvement are often required. Potential adverse effects of laser and intense pulsed light therapy include skin dyspigmentation, blistering, ulceration, and scarring. The pharmacologic agent with the strongest evidence for efficacy for treating persistent facial erythema in rosacea is topical brimonidine. Brimonidine tartrate, a vasoconstrictive alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonist used in the treatment of open angle glaucoma, has emerged as a treatment for rosacea-associated facial erythema. The efficacy of this agent when applied topically is supported by the results of phase II and phase III randomized trials.26,27 Topical brimonidine 0.33% gel appears to be well tolerated.28 The most common adverse effects are erythema, flushing, skin burning sensation, and contact dermatitis. The occurrence of severe, transient rebound erythema several hours after application has been reported.29,30 The occurrence of persistent erythema in skin adjacent to the site of long-term brimonidine application has also been reported.31 The true incidence of worsening erythema is not known but has been estimated to be up to 20 percent.32 Patients should be counselled about these side effects prior to therapy. Topical metronidazole, azelaic acid, and topical ivermectin are considered first-line therapies for mild to moderate disease with evidence from randomized trials and systematic review supporting their efficacy and safety.33 The lower cost of metronidazole 0.75% gel (the least expensive formulation of metronidazole) compared with azelaic acid and ivermectin favors the initial use of metronidazole. The mechanism through which metronidazole improves rosacea is unknown, but may involve antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, or antioxidant properties.34 Topical metronidazole is most effective for the treatment of inflammatory papules and pustules. It is generally well tolerated; the most common adverse effects are local irritation, dryness, and stinging sensations.35 Azelaic acid improves papular and pustular lesions and may also reduce erythema with skin discomfort as its most frequent side effect. Topical ivermectin is also useful for papular and pustular lesions, and is well tolerated. Patients who present with numerous inflammatory papules or pustules, or those with milder disease who fail to respond to one or more topical therapies may benefit from oral antibiotic therapy. Tetracyclines are the best-studied agents amongst the oral antibiotics used to treat rosacea. Tetracycline, doxycycline, and minocycline have been used for many years for the management of rosacea. These agents are most useful for improving inflammatory papules and pustules, and may also reduce erythema. 36,37Since no definite microbial cause of rosacea has been identified, the efficacy of oral antibiotics in rosacea is often attributed to their anti-inflammatory properties.38 Due to the concern over possible development of antibiotic resistance, interest has grown in the use of subantimicrobial doses of antibiotics, which retain its anti-inflammatory properties but lack antibacterial effects. After treatment with oral tetracycline, doxycycline, or minocycline for 4 to 12 weeks, improvement may be maintained with topical agents or subantimicrobial doxycycline. Adverse effects of oral tetracyclines include gastrointestinal distress and photosensitivity. Minocycline is the least photosensitizing of these agents, but it may cause vertigo, a lupus-like syndrome, and skin discoloration. Tetracyclines should not be given to children under nine years old due to the risk of permanent tooth discoloration and reduced bone growth. Patients who fail to respond to topical therapies and oral antibiotics may improve with oral isotretinoin.39 However, although oral isotretinoin can bring about improvements in inflammatory lesions and facial erythema, high quality data on the efficacy of isotretinoin for rosacea are scarce, and the ideal regimen for treatment has not been established. Also, oral isotretinoin is not used as the first-line therapy due to its many adverse effects including cheilitis, dry skin, abdominal pain and teratogenicity. Ocular RosaceaOcular involvement in rosacea can result in damage to the ocular tissues. Patients with signs or symptoms of ocular involvement should be referred to an ophthalmologist for further evaluation. Childhood RosaceaChildhood rosacea is managed similarly to rosacea in adults. However, the use of oral tetracyclines should be avoided in children under nine years old. A treatment algorithm for rosacea is shown in Figure 4.   Psychosocial care for patients with rosaceaRosacea can have a negative psychological impact on the daily life and may contribute to the development of depression40, lowered self-esteem, embarrassment and feelings of shame.41 It had been reported that engaging in emotion-focused and behavioural/avoidant-focused coping strategies increased participants’ confidence and reduced their avoidance of social situations. However, such strategies might still serve to maintain underlying unhelpful cognitive processes. Consequently, it is important for medical professionals to assess the presence of cognitive factors that might contribute to and maintain the distress in patients with rosacea, and when unhelpful thoughts or beliefs are reported, patients may need to be referred for psychological support.41 Family physicians, when looking after patients with rosacea, should also assess their psychosocial health, provide appropriate care and make referrals to psychological health specialists if and when necessary. ConclusionRosacea is a chronic relapsing inflammatory skin disorder. Patients suffering from this disorder can suffer physically, psychologically and socially. Family physicians have the advantage of being in a continual professional relationship with their patients so as to provide holistic care for them. The phenotype of rosacea, instead of clinical subtype, determines the approach to physical treatment. The family physician should monitor the patient’s psychosocial condition, provide appropriate care, and consider referral to a dermatologist or clinical psychologist for severe conditions or when improvement is unsatisfactory.

Wai-man Yeung, FRCSEd, FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Correspondence to: Dr Wai-man Yeung, Associate Consultant, Peng Chau General

Out Patient Clinic, 1A, Shing Ka Road, Peng Chau, Hong Kong

SAR.

References:

|

|