|

June 2018, Volume 40, No. 2

|

Update Article

|

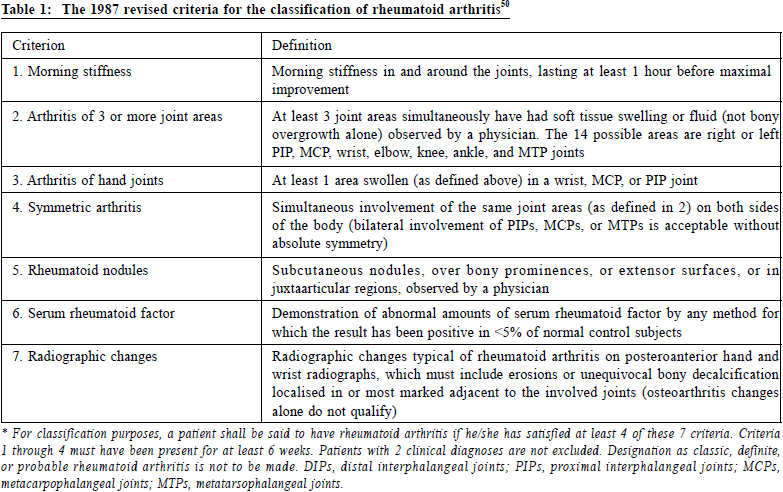

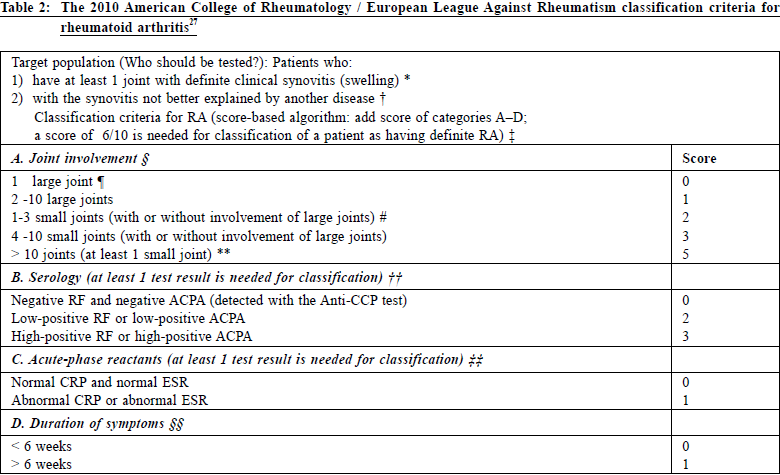

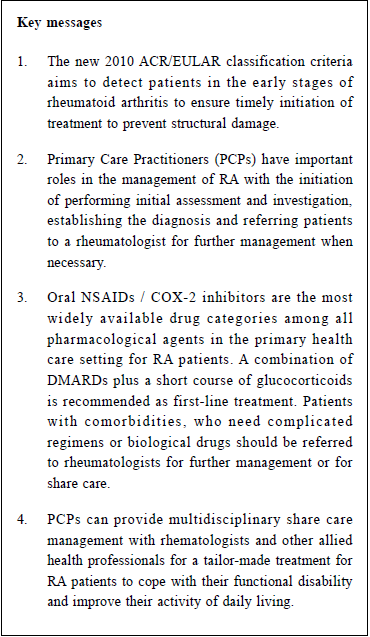

A review on the diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis in general practiceWing-ho Shiu 邵永豪,Tseng-kwong Wong 黃增光,David VK Chao 周偉強 HK Pract 2018;40:61-72 Summary Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic autoimmune disease mainly affecting joints causing pain, stiffness, swelling, deformity and subsequently resulting in joint destruction and loss of function. Together with its non-articular manifestations, RA has a great impact on the physical, psychological and social aspects of its sufferers. Although RA is not so prevalent in Hong Kong, it is the most common type of autoimmune arthritis. Primary care physicians (PCPs) have a unique role in the preliminary diagnosis and in commencement of early treatment in order to prevent joint destruction and functional disability, and to achieve a better disease remission. Furthermore, shared care management on RA patients with rheumatologists can be a cost effective way to help our patients. A multidisciplinary team involving doctors in different specialties and allied health professionals can provide better assessment and offer a variety of treatments to patients. ` 摘要 類風濕性關節炎是一種慢性、系統性自身免疫性疾病,主要 影響關節導致疼痛、僵硬、腫脹、變形,從而令關節損毀並 失去功能。加上這個疾病會影響關節以外身體的其他部分,因此對病人的生理、心理及社交各方面也可以造成重大影響。雖然這疾病在香港患病率較少,但它是最常見的一種自 身免疫性關節炎症。基層家庭醫生在於初步診斷、及早展開治療以防止關節損壞及失去功能、以達致緩解病情上,有其 獨特的角色。此外,家庭醫生與風濕病學專科醫生共同參與 診治病人,可更有成本效益地幫助病人。而一個由不同醫生 及專職醫療服務人員組成的多重領域的團隊,可為病人提供 適切的評估及多元化的治療。 IntroductionRheumatoid arthritis (RA) affects between 0.5% and 1% of adults in the developed world; between 5 to 50 per 100,000 people newly developing the condition each year.1 Onset usually occurs between 30 and 50 years of age and women are affected 2.5 times more frequently than men.2 In 2013, RA patients ended in 38,000 deaths, up from 28,000 deaths in 1990.3 In Hong Kong, RA is less prevalent than in other developed countries. Hong Kong reported a prevalence of 0.35%.4 It is estimated that twenty to thirty thousands people suffer from different types of rheumatism. According to the statistics of the Hospital Authority (HA)5, between 2004 and 2006 there were over 11,800 following-up cases of rheumatism at the Specialist Outpatient Clinics (SOPCs), more than 40% of which were RA. The death risk of RA patients is three to four times that of a normal person. The death rate increases in proportion with the number of damaged joints. RA is the most common type of autoimmune arthritis. It is a chronic, systemic, inflammatory disease causing joint pain, swelling, stiffness and progressively leading to joint destruction, deformity and loss of function. It has a great impact on the physical, psychological and social aspects of its sufferers. Although there is no cure for RA, early diagnosis and treatment can effectively achieve disease remission6, prevent physical disability and premature death. PCPs can play an important role in the early diagnosis of RA and can provide prompt and appropriate treatment via a multidisciplinary approach. AetiologyThe aetiology and pathogenesis of RA are unclear. It belongs to a heterogeneous group of diseases. The cause is multifactorial and involves genetic and environmental factors. The possible predisposing factors for the development of RA included genetic factors7,8,9, immunological factors10, sex hormones11, hyperprolactinaemia12 and infectious agents.13, 14 Delay in the diagnosis and treatment may compromise the outcome in RA. Some patients may progress as a chronic disease while others only have a self-limiting condition. Several prognostic factors have been linked with unfavourable outcomes of RA in terms of joint damage and disability. Prognostic factors include chronic smoking15,16, high titer of Rheumatoid Factor (RF)17 and Anti-cyclic citrullinate peptide (Anti- CCP)18, early onset of radiological erosion19, high disease activity at baseline, positive family history and extra-articular manifestations.20 Anti-CCP is one of the new biomarkers that can predict an aggressive disease course, which often accompanies joint destruction. It was shown that there may be a “window of opportunity” in the early stage of RA where it may be possible to alter the course of disease if rheumatoid arthritis activity is tightly controlled.21 RA patients suffering from disease flare up and remission periodically may increase their risk of disability. Role of primary care physiciansMusculoskeletal complaint is one of the most common conditions that primary care physicians would encounter. It may be the manifestations of an underlying inflammatory arthritis. PCPs are often the physicians to provide first contact care and evaluation for patient with musculoskeletal problems. One study showed that delayed presentation to PCPs was the main reason why patients with rheumatoid arthritis were seen late by rheumatologists.22 The initial management should include diagnostic tests, treatment, provision of advice and referral. There is often a diagnostic delay with many RA patients and time-lag from symptom onset to the first rheumatologist visit. PCPs have a unique role with early diagnosis and even initial appropriate medications including disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs).23,24 As RA is a chronic disease, it was suggested that long-term follow-up by PCPs in a shared care approach with rheumatologists can bring notable improvements and benefits. The absence of partnership can lead to higher health care costs with less improvement in clinical condition.25 In Britain, the National Health Service (NHS) has a shared care system on DMARDs prescription between hospital rheumatologists and PCPs.26 Hospital rheumatologists first initiate DMARDs, and then PCPs are invited to continue the drug prescription and participate in the shared care in accordance with the treatment plan from the hospital rheumatologists once the patient has reached a stable condition. There is a mechanism in place which allows rapid referral of a patient from PCPs when and if the patient’s clinical condition deteriorates. PCPs have the responsibilities to follow the monitoring requirements according to the guideline recommendations (i.e. the DMARDs dosage and side effects, regular blood and urine tests and other additional clinical assessments if and when appropriate), to seek advice from the rheumatologists on any aspect of patient care that is of concern and may affect treatment, and to refer patients with a deterioration of their condition back to the rheumatologists for further review. Clinical approachWhen suspecting a patient of having RA, the initial steps in management include performing a baseline evaluation, establishing the diagnosis early with reference to the diagnostic criteria, documenting the baseline disease activity and damage, and estimating his/her prognosis. Diagnostic criteriaThe American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria 1987 used to distinguish rheumatoid arthritis, from other rheumatological diseases (Table 1) is not helpful in identifying patients at the stage where early effective treatment can be initiated. Hence a new classification (Table 2)27 was developed by a joint working group from the ACR and The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) for rheumatoid arthritis in which the scoring system would not rely on the later changes e.g. bone erosion and extra-articular disease. It facilitates the assessment of early stage of arthritis and serves as the basis for starting DMARDs.

According to the 2010 ACR / EULAR classification criteria, to diagnose a patient as having RA, we need to fulfill two mandatory requirements. Firstly, there is at least one joint with definite clinical synovitis (i.e. swelling). Secondly, the synovitis is not better explained by another diagnosis. Four additional criteria, namely joint involvement, serology, acute-phase reactants and duration of symptoms, can then be applied to eligible patients. A score of 6 or above out of a total score of 10 is indicative of the presence of definite RA. The focus of the 2010 ACR / EULAR classification criteria is to enable earlier diagnosis and treatment. As bone erosion (one of the 1987 ACR criteria) is not considered for inclusion in the scoring system, those patients with bone erosion who should be considered during the diagnostic process27 may present at a late stage. To maintain a single classification system for RA, an additional three groups of patients should be considered to be classified as suffering from RA:

Family physicians have a role to play in the regular review and reapplication of classification criteria for those patients with very early disease that may not fulfill the new criteria in the initial assessment. The 1987 ACR (RA) criteria’s sensitivity in detecting early disease is limited. Several cohorts have shown that the 2010 ACR / EULAR classification criteria improves early disease identification and can reclassify as rheumatoid arthritis, patients who do not meet the 1987 ACR criteria and would otherwise have been labeled as undifferentiated arthritis.28,29 They also allow physicians to initiate early treatment without delay. Laboratory testsRheumatoid factor (RF) is a frequently ordered test in general practice. It has a sensitivity and specificity of 69% and 85% respectively.30 A high titre is associated with severe disease, erosions and extra-articular disease. On the other hand, Anti-CCP is more specific than RF for diagnosing RA and better predicts radiographic progression of joint erosion, and has a sensitive and specificity of 67% and 95% respectively.31 Both RF and Anti-CCP have been incorporated into serology criterion of the new 2010 ACR / EULAR classification, and the Anti-CCP testing helps to enhance early diagnosis as compared to RF.

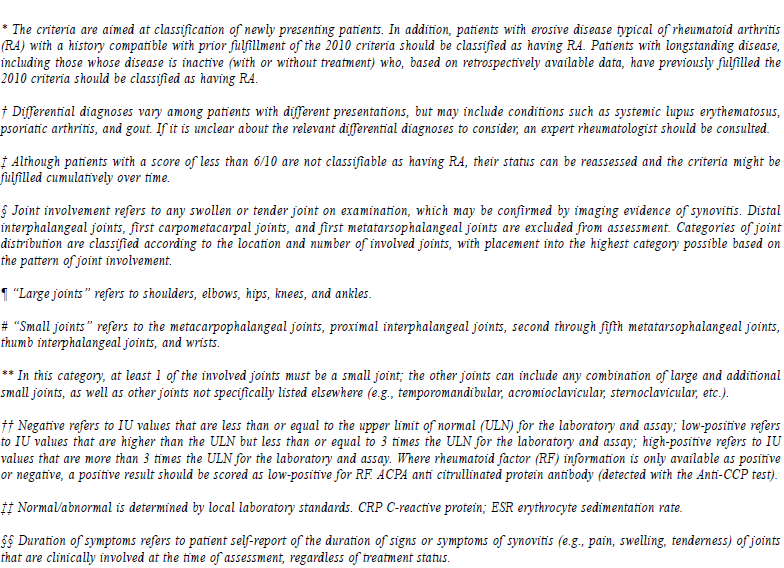

For the radiological assessment, X-rays of hands and feet may show soft tissue swelling, juxta-articular osteopenia and decreased joint space. Bone erosions, subluxation and complete carpal destruction may occur at a later stage of the disease. In contrast, ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have a greater sensitivity in detecting bone erosions than X-rays, identify synovitis more accurately and can identify the earlier stages of disease.32 Despite the benefits of Ant -CCP testing, ultrasound and MRI for the early diagnosis of RA, they are not cost effective if used routinely for every patient who presents with joint symptoms.33 They can be considered for the early diagnosis of RA in patient with an atypical presentation. Ultrasound and MRI can help identify early stage disease in some difficult cases, and provide radiological guidance if joint aspiration and injection were being considered by rheumatologists.33 Monitoring of disease activityThe Disease Activity Scale in 28 joints (DAS28) (Figure 1) is a useful instrument for monitoring disease activity, evaluating disease progression and treatment response. It includes four variables: i) number of tender joints from among 28 joints, ii) number of swollen joints from among 28 joints, iii) erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP), and iv) patient’s assessment of general health status34. This is not a simple formula, but can be calculated using a pre-programmed calculator or other computing devices. The DAS28, with a number on a scale from 0 to 10, indicates the current activity of the patient’s rheumatoid arthritis.35 A DAS28 above 5.1 means high disease activity whereas a DAS28 below 3.2 indicates low disease activity. Remission is indicated by a DAS28 lower than 2.6. In addition, self-reported physical and mental health status are also important as part of the assessment of patient’s health-related quality of life and functional disability. The Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) and SF-36 Health Stats Questionnaire are the assessment tools commonly used. The HAQ is commonly used for health status measurement and primarily for determining functional disability. There are eight sections in HAQ (dressing, arising, eating, walking, hygiene, reach, grip and activities) with patient scoring. The result is shown as a disability index (DI) or functional disability index (FDI).36, 37 The SF-36 assesses the physical limitations and emotional status of patients. It consists of 36 questions (items) related to eight health concepts including physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality (energy / fatigue), social functioning, role limitations due to emotional health, general mental health (psychological distress / wellbeing). Response to each of the SF-36 items are scored and summed using a standardised scoring protocol. Higher scores represents a better self-perceived health state.38 Assessment of cardiovascular risk factors and bone mineral densityThe incidence of stroke and myocardial infarction for RA patients are higher than that of the general population.39, 40 Assessment and control of cardiovascular factors with evidence-based advice related to smoking, diet, body weight, exercise and blood pressure are very important parts of the management plan. In addition, RA patients are a high-risk group for fragility fracture and osteoporosis.41 There are recommendations from EULAR42 and local rheumatologists33 that RA patients should be screened for bone mineral density. Initiation of drug treatment and monitoring of disease progress are mandatory for those with osteoporosis. ManagementGuidelines suggest that anyone with early inflammatory arthritis should be referred to a rheumatologist within 3 months of disease onset whenever possible. It was shown that there might be a “window of opportunity” in the early stage of RA where it may be possible to alter the course of disease if it is tightly controlled.23

NICE guideline suggested referring patients with suspected persistent synovitis of undetermined cause for specialist opinion.43 Urgent referral is suggested if the small joints of the hands or feet are affected, more than one joint affected or if there has been a delay of 3 months or longer between onset of symptoms and seeking medical advice. Besides, patients with clinical symptoms whose blood tests show a normal acute-phase response or negative rheumatoid factor is also indicative of referral. For patients who meet the diagnostic criteria or clinically suspected of suffering from RA, PCPs may consider initiation of drug treatment and early referral to a rheumatologist for further treatment or shared care. For PCPs having shared care with a rheumatologist, they can monitor the patient’s functional state, disease activity, medication side effects and consider referring back to the rheumatologist for early review when there is a deterioration in the patient’s clinical condition. The British Society for Rheumatology44,45 suggested that clinicians and allied health professionals with regards to the use of DMARDs should withhold treatment and liaise with the specialist team in charge of the patient’s treatment if the following were noted:

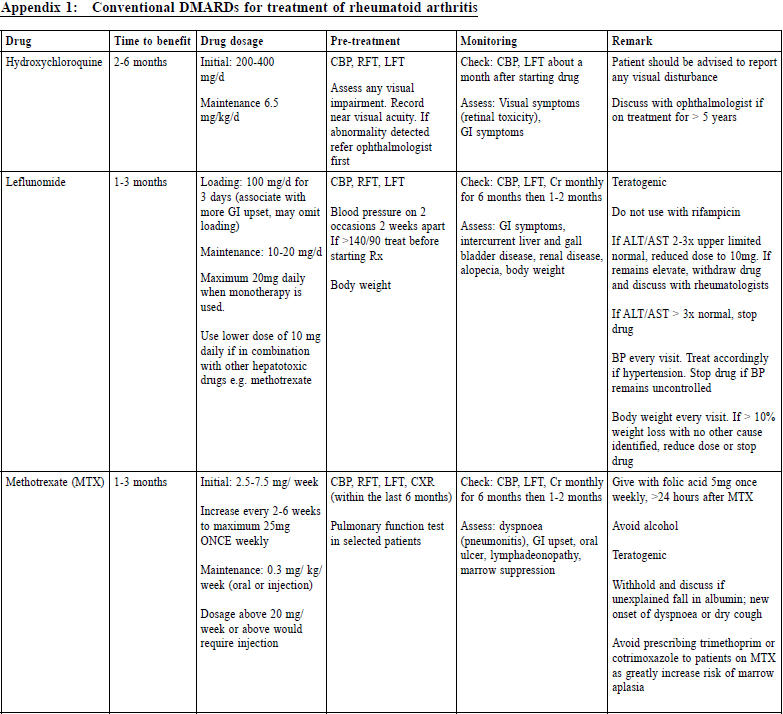

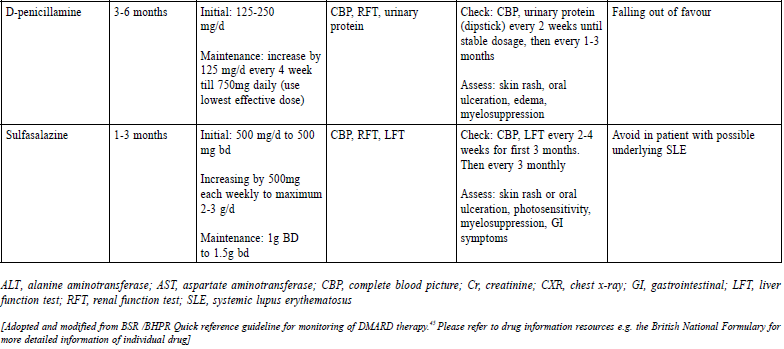

There is evidence that allied health professionals (AHPs) have their role in caring for patients with rheumatoid arthritis.46 This is in terms of pain management, sleep advice, exercises, posture care, pacing and activity, education programme on psychological coping, joint protection, energy conservation, hand-strengthening and mobilising home exercises. There are no standardised referral criteria for allied health services for RA patients. It is commonly done for confirmed RA cases that are under the care of rheumatologists. As a PCP, participating in the multidisciplinary care of RA patients and in the making of appropriate referrals to AHPs would be of benefit to these patients. Vaccination for rheumatoid arthritis patientsThe ACR 2015 RA Guideline47 suggested that RA patients on DMARDs can consider being vaccinated with the pneumococcal, influenza, hepatitis vaccines (all are killed vaccines) and human papilloma vaccine (which is recombinant vaccine) if indicated based on age and risk. In contrast, for RA patients who are planning biological treatment, herpes zoster vaccine (live attenuated vaccine) can be considered prior to receiving treatment. However, this vaccine is not recommended for those already on biological drugs. Pharmacological treatmentDepending on the knowledge and experience of PCPs, the following are the drug treatment options for RA patients. However, in general, we propose that patients with comorbidities, who need complicated regimens or biological drugs due to disease severity, and who are intolerant to treatment side effects should be referred to rheumatologists for further management or for share care. There is currently no curative treatment for RA. Disease remission (i.e. DAS28 < 2.6) had become the accepted treatment goal to arrest joint damage and reduce the likelihood of long-term disability.33 Early treatment of RA results in better response rates and a higher probability of drug-free remission. Disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARD)sThey have the potential to reduce or prevent joint damage, preserve joint integrity and function. It is suggested that DMARDs should be initiated ideally within 3 months for any patient with an established diagnosis of RA. A combination of DMARDs plus a short course of glucocorticoids is recommended as firstline treatment.47 Local consensus recommendations on RA management33 for our locality are available. The recommendations are as follows:

They have anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties but do not alter the course of the disease or prevent joint destruction. It is the most widely available drug category among all pharmacological agents in the primary health care setting for treating RA patients. Oral NSAIDs / COX-2 inhibitors should be used for the shortest possible duration and at the lowest effective dose. They should be co-prescribed with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) to reduce the chance of gastrointestinal side effects. Analgesic such as paracetamol, codeine or compound analgesics are recommended to those whose pain control is not adequate and to reduce their need for long-term NSAID and COX-2 inhibitors according to the NICE guideline. If symptom control is not satisfactory with the use of NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors, a review of the DMARDs regimen by a rheumatologist is suggested.43 GlucocorticoidsThey are used as a short-term treatment for the management of flares in people with a recent onset or established disease to rapidly decrease inflammation. They are the commonest cause of secondary osteoporosis. Treatment for more than 3 months or with repeated courses is a risk, and concomitant administration of calcium with vitamin D and bisphosphonates is necessary.51 The continued longterm use of glucocorticoids should only be considered when all other treatment opinions (including biological drugs) have been offered and the drug complications have been fully discussed.43 The ACR 2015 RA guideline47 defined low dose glucocorticoid usage as less than 10mg/day of prednisolone (or equivalent) and short-term usage as less than 3 months. Biological drugsFor patients who continue to present with active disease despite MTX, the addition of another conventional DMARD or biological agent should be considered.33 Patients who require MTX plus a biologic agent may be administered with any one of the following combinations: MTX plus an anti-TNF-α agent, including tocilizumab, abatacept, or rituximab. Anti- TNF therapy failure patients may be given another anti-TNF-α agent, including tocilizumab, abatacept or rituximab.33 The balance of clinical benefits and cost effectiveness needs to be considered when using biological drugs. Patients should be referred to a rheumatologist for further discussion when biologic agents are required. Furthermore, screening RA patient for hepatitis and tuberculosis (TB) before starting biological agents is recommended by ACR 2015 RA Guideline.47 For those patients with hepatitis, prophylactic antiviral drug is required concomitantly with biological drugs. For patients who have active or latent TB (based on the initial tuberculin skin test (TST) or interferongamma- release assay (IGRAs) and subsequent chest X-ray findings), they should be referred to a specialist for appropriate anti-TB treatment before starting biological drugs. Surgical treatmentNICE guideline suggests that RA patients should be referred to specialists for surgical opinion if there is persistent pain due to joint damage or other identifiable soft tissue causes, worsening joint function, progressive deformity, persistent localised synovitis, tendon rupture, nerve compression, stress fracture, septic arthritis and suspected cervical myelopathy.

Multi-disciplinary careApart from share care management between PCPs and rheumatologists, a multidisciplinary team involving psychologist, physiotherapist, occupational therapist and podiatrist can provide periodic assessment on patients’ condition and help better manage their disease.43 Firstly, we can refer patients to a physiotherapist to improve the patients’ general fitness by encouraging them to have regular exercise, to teach them joint flexibility exercises, muscle strength and to manage other functional impairments. Secondly, we can offer patient access to an occupational therapist if they have problems with their hand function or difficulties in coping with daily activities. Thirdly, referral to a clinical psychologist could be made for a variety of treatments related to their disease, e.g. relaxation and cognitive coping skills. Finally, for patients with foot problems, podiatrists can provide assessment and offer a variety of treatments including functional insoles and therapeutic footwear if indicated. ConclusionPCPs often provide first contact care for patients with suspected RA who may initially present with nonspecific musculoskeletal problems. They have important roles in the management of RA including initial assessment and investigations, establishing the diagnosis and referring patients to a rheumatologist for further management when and if deemed necessary. Initiation of DMARDs early in primary care is possible to avoid treatment delay. In addition, for those patients with known RA, PCPs can provide share care management with rheumatologists. PCPs can also coordinate with other allied health professionals for a tailormade management to help patients to cope with their functional disability and improve their activity of daily living.

Wing-ho Shiu,MBChB(CHUK), FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM(Family Medicine) Correspondence to:Dr. Wing-ho Shiu, Resident Specialist, Department of Family

Medicine and Primary Health Care, United Christian Hospital,

130 Hip Wo Street, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong SAR.

E-mail: shiumatt@gmail.com

References:

|

|