|

June 2018, Volume 40, No. 2

|

Case Report

|

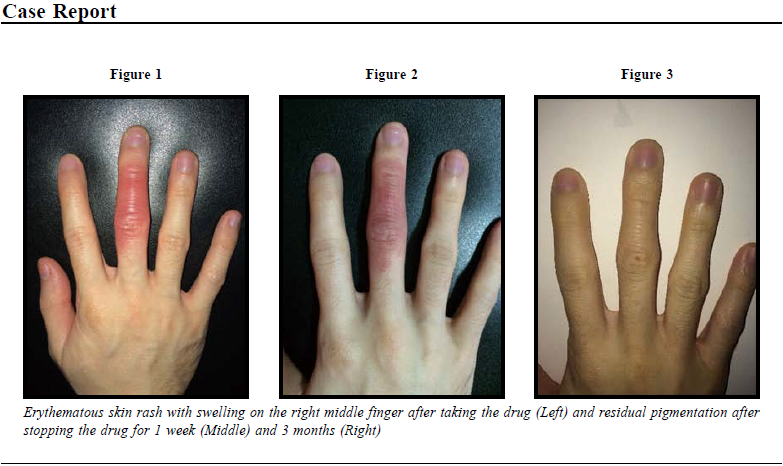

Fixed drug eruption – a case presentation and literature reviewChris KV Chau 周家偉 HK Pract 2018;40:57-60 SummaryFixed drug eruption (FDE) is not uncommon in our daily clinic practice. However, it may be missed if we do not pay adequate attention to the drug history of our patients. The presentation is usually typical. Failing to identify the causative agent renders the patient to suffer from repeated attacks and causes unnecessary anxiety and embarrassment. 摘要在我們日常臨床工作中,固定性藥疹並不罕見。但如 果我們沒有充分注意病人的藥物史,可能會錯過診斷的機 會。臨床的表徵通常是典型的。若未能識別引致藥疹治病 的藥物,藥疹會反復發作,並使患者感到不必要的焦慮和 尷尬。 Case presentation“Doctor, my middle finger turns red easily. It is so embarrassing!” A 25 years old student presented with sudden onset of rash over his right middle finger. He had no recent injury or insect bite. The patient did not contact any chemicals that could explain his condition. He enjoyed good health except that he had allergic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, and acne vulgaris. He consulted a GP and was treated as skin infection. A course of Ampicillin and Cloxacillin was prescribed and symptoms subsided gradually. However, the rash reappeared 2 days after finishing the antibiotics. The patient consulted another doctor. On physical examination, there was bright red swelling over dorsal side of right middle finger (Figure 1). Finger joints were normal. A course of antibiotic (amoxycillin and clavulanic acid) was prescribed. The symptoms subsided gradually. Two weeks later, similar skin rash reappeared on his right middle finger. Diagnosis at that time was cellulitis. Low dose steroid cream together with a course of antibiotic (amoxycillin and clavulanic acid) were prescribed. The rash subsided gradually leaving some purplish brown pigmentation. Same episodes occurred for three times and the rash on his middle finger caused anxiety and embarrassment. Further inquiry into patient’s drug history revealed that he was currently taking another antibiotic (doxycycline) intermittently for treatment of his acne problem. The patient recalled whenever he took doxycycline, the rash appeared sometime later. He stopped doxycycline whenever he had treatment for his “cellulitis”. The incidental withdrawal of doxycycline misled us to think that it was the “cellulitis” which responded to the antibiotic treatment. Given the strong temporal relationship between the drug and symptoms, probable diagnosis of fixed drug eruption was made. The patient had acne problem for years. His doctor prescribed a 2-week course of doxycycline in view of his fair response to topical treatment. He started to have localised skin rash on his finger one week later. The time lag for appearance of skin rash after taking the drug was gradually shortened. It took only a few hours in the last episode before flaring up of the same rash that has caught patient’s attention. ManagementDoxycycline was stopped immediately. He was prescribed with steroid cream and antihistamine for symptomatic relief. Two weeks later, symptoms were subsided with some pigmentation (Figure 2) left. The lesion was almost completely resolved after 3 months (Figure 3).

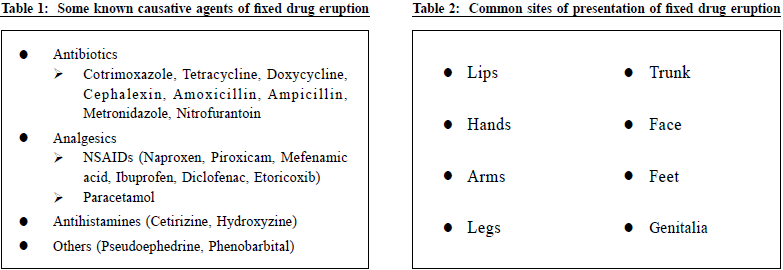

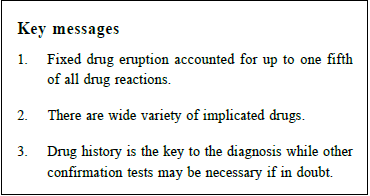

Oral drug reaction is not always generalised in distribution; fixed drug eruption (FDE) can be very localised. Whenever encountering cases presented with skin rash reappearing on the same site; history of concurrent use of drug should be carefully inquired. FDE may be trivial but it can cause social embarrassment and emotional disturbance due to cosmetic reasons. Literature reviewIntroductionFixed drug eruption was first described in 1890s.1,2 It is a distinctive variant of drug induced dermatoses characterised by a single or several erythematous, eczematous, or bullous plaques on skin or mucous membranes.1,2,3 By definition, the drug reaction recurs in the same location with repeated drug administration. FDE is usually self-limiting if the exposure is halt, otherwise relapsing lesions can be annoying and embarrassing. EpidemiologyFDE affects patients of all age groups from infants to elderly.2 The reported mean age of presentation is in 20s- 30s2,3,4,5 while there is no gender preference.2 As many as 2 to 3% of patients would develop drug reactions after taking drugs; among them, FDEs accounted for 9 to 22% of these drug reactions as reported in literature.5,6 According to the World Health Organisation Collaborating Centre for International Drug Monitoring, the Uppsala Monitoring Centre causality assessment criteria3, patients were classified into categories of definite (confirmed with patch test or drug provocation test), probable (causative drug identified based on patient's history) as in this case, possible (clinically consistent but unable to identify causative drug) or unlikely FDE. Causative AgentsCausative agents comprised more than 100 implicated drugs.7 Their respective incidence changes over time and varies in different countries. Commonly implicated drugs are co-trimoxazoles, penicillins including Amoxycillin and Amoxil, Tetracycline and Doxycycline, Barbiturates, Phenolphthalein, Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), Paracetamol and Gold salts (Table 1). Following the advancement of pharmacology, newer drugs2,3,8,10,11,12,13 such as Cox-2 inhibitors2 and antineoplastic agents8 are found to be causative agents of FDE, which did not exist decades ago. Clinical PresentationPruritus is rare, pain and burning discomfort are possible while majority (76%) of patients may not have symptoms.2 They may present as solitary (16.2-30.6%) lesion. However, with repeated attacks, new lesions may appear and present as multiple lesions (59.4-79%).2,3,9The time lag can be up to 2 weeks post drug exposure.1 After repeated exposure, the time lag of appearance of lesions post drug administration is shortened. The lesion can appear as fast as within 30 minutes.15

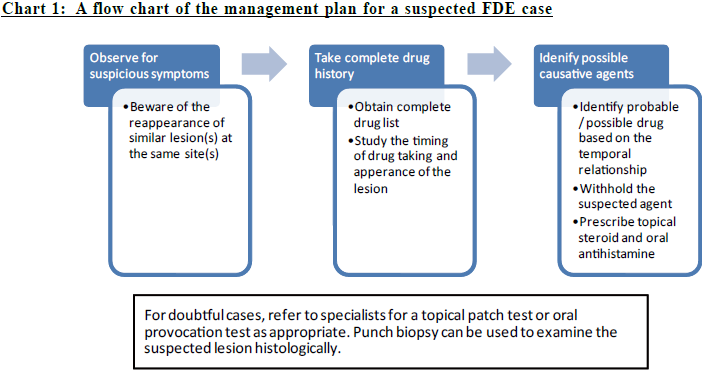

The lesions maybe circular in shape in more than half of cases.2 Lesions can occur on skin or mucosa or both.12,13 The common sites2,3,9,14,15 are the limbs, the trunk; the hands and feet (Table 2). Genitalia (glans penis) and perianal areas are also commonly involved. Lesions may occur around the mouth or the eyes. The genitals or mouth lesions may be involved in association with skin lesions or on their own. Rarely, the lesions can be seen in buccal mucosa and tongues. As healing occurs, crusting and scaling are followed by a persistent dusky brown or violaceous colour (hyperpigmentation) at the site that may fade, but often persists between attacks. There is no specific drug-site relationship although literature13 reported there may be site-preference with certain agents. For example, cotrimoxazole frequently induce lesions on genital mucosa and naproxen on lips. The differential diagnosis of FDE include other targeted lesions: infection such as herpes simplex and syphilis, contact dermatitis, phytophotodermatitis, erythema multiforme, and ecthyma gangrenosum.9,16 However, literature4 reported uncommon presentation of FDE, which are erythema multiforme -like FDE, toxic epidermal necrolysis-like FDE, linear FDE, wandering FDE, non-pigmenting FDE and bullous FDE. PathophysiologyWith recent advancement of immunological technology, the pathological mechanisms of FDE are better studied.17,18,19,20,21,22 Histopathology has shown that there is accumulation of T cells which reside in the skin lesions. CD8(+) T cells are believed to have played a role. These cells are specialised to mediate protective immunity. Their excessive activation may result in the development of organ-specific inflammatory responses. The presence of CD8(+) intraepidermal T cells with the effector memory phenotype in the lesions may explain the variety of clinical and pathologic features observed in FDE lesions. ManagementSince the culprit drug is the cause of the pathology, it is essential to identify this agent. Avoidance of this drug and chemically related drugs3,4,9 is of paramount importance in the management of FDE. Thorough history taking is usually adequate to delineate the offending agents in most of typical cases. For suspicious cases, we can refer them to dermatologists for topical patch test or oral drug provocation test23,24, which are conducted by administration of very low dose of suspicious agent to the patient; the appearance of lesion at the same site is regarded as positive result. The diagnosis can be confirmed by taking punch biopsy4,8 of the lesion for histopathologic examination. Topical glucocorticoid can be administered on the lesions in addition to prescribing antihistamine for symptomatic treatment.12,13,14 Systemic steroid is rarely used except in more generalised FDE cases. A flow chart summarises the management plan as an easy reference.

AcknowledgementI would like to thank my patient who is willing to share his story as well as mobile phone pictures.

Chris KV Chau,MPH (Johns Hopkins), FRACGP, FHKCFP, FHKAM (Community Medicine)

Correspondence to:Dr Chris KV Chau, Resource Information Room, 5/F, Tsan Yuk

Hospital, Hospital Road, Hong Kong SAR.

E-mail: cchaukv@yahoo.com

References:

|

|