|

March 2017, Volume 39, No. 1

|

Original Article

|

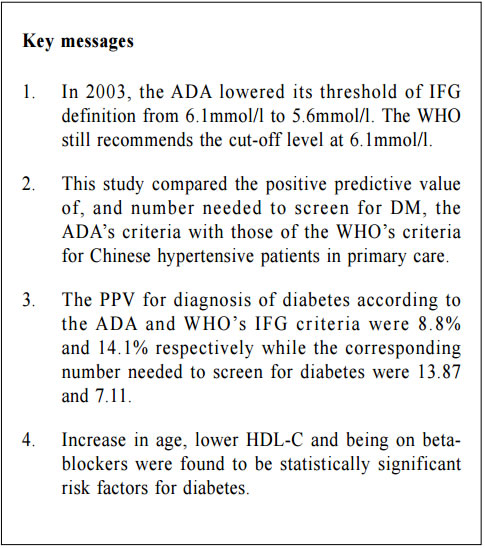

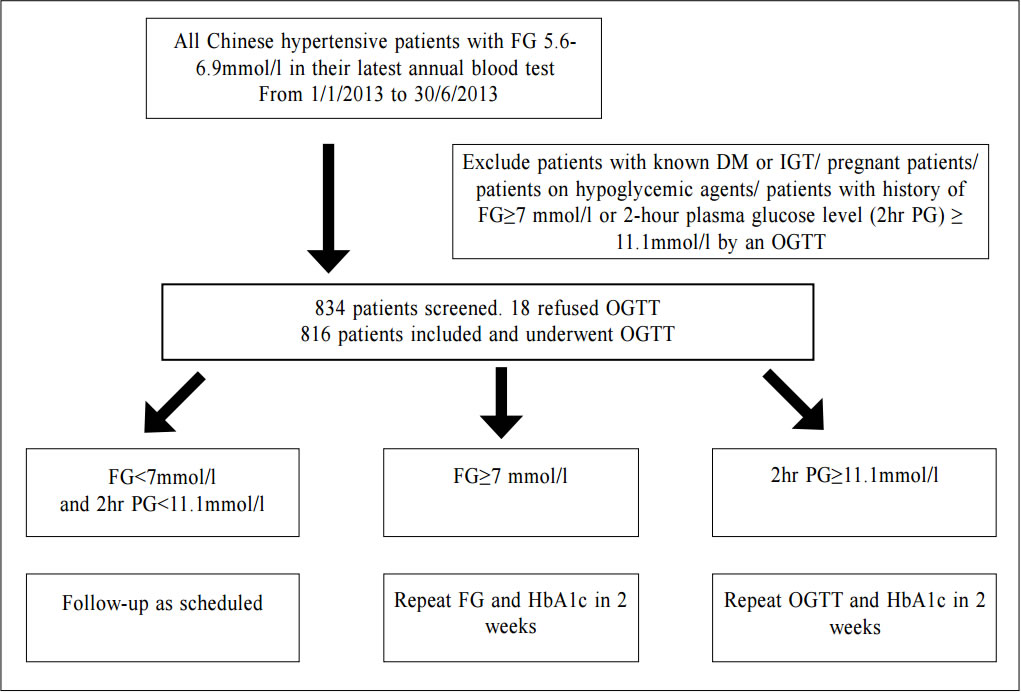

Impaired fasting glucose (IFG) among Chinese hypertensive patients in two Hong Kong primary care clinics: use the ADA criteria or WHO criteria?Ming - lam Tsang 曾明霖, Pang - fai Chan 陳鵬飛, Loretta KP Lai 黎潔萍, Kai - lim Chow 周啟廉, Matthew MH Luk 陸文熹,Sze-nga Wong 黃詩雅,David VK Chao 周偉強 HK Pract 2017;39:2-12Summary Background: In 2003, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) lower edits threshold of IFG definition from 6.1mmol/l to 5.6mmol/l. The World Health Organization (WHO) still recommends the cutoff level at 6.1mmol/l. Early detection and management of diabetes among hypertensive patients could improve cardiovascular risk. An evidence-based local definition of IFG could guide our doctors to the better usage of our resources for diagnosing diabetes. Objectives: To compare the positive predictive value (PPV) of the ADA’s IFG criteria and the number needed to screen, with those of the WHO’s criteria, to predict and diagnose diabetes for Chinese hyper tensive patients in primary care. Subject and design: Chinese hypertensive patients from two general outpatient clinics were arranged to have a standard 75g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) if they were screened to have IFG level of 5.6mmol/l according to the ADA guideline from 1st January 2013 to 30th June 2013. If the 2-hours glucose level was ≥ 11.1mmol/l, blood tests for OGTT would be repeated together with HbA1c. If the fasting glucose (FG) of the first OGTT was already ≥ 7mmol/l, then only FG and HbA1c would be performed. Main outcome measures: Positive predictive value for diagnosis of diabetes and the number needed to screen by using the ADA and WHO diagnostic criteria of IFG for diabetes testing with OGTT. The risk factors associated with diabetes in patients with IFG. Results: 7.2% (45/624) and 14.1% (27/192) patients were diagnosed diabetes in the FG 5.6-6.0mmol/l group and FG 6.1-6.9mmol/l group respectively. The PPV for diagnosis of diabetes according to the ADA and WHO’s IFG criteria were 8.8% and 14.1% respectively while the corresponding number needed to screen for diabetes were 13.87 and 7.11. Increase in age (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.00-1.05, p=0.046), lower HDL-cholesterol level (OR 0.42, 95% CI 0.20-0.89, p=0.023), being in IFG 6.1-6.9mmol/l group (OR 2.13, 95% CI 1.24-3.66, p=0.006) and on beta-blockers (OR 2.43, 95% CI 1.45-4.06, p=0.001) were found to be statistically significant risk factors for diabetes. Conclusion: By using the lower IFG diagnostic threshold of ADA diagnostic criteria, the positive predictive value of DM in Chinese hypertensive patients would be decreased significantly. Although we are not certain about the cost-effectiveness to screen for diabetes in all Chinese hypertensive patients with a lower IFG cut-off value, screening is recommended in those with associated risk factors. Keywords: Impai red fast ing glucose, diagnost ic criteria, diabetes, Chinese hypertensive patients, primary care 摘要 背景:在2003年,美國糖尿病學會(ADA )將空腹血糖 異常的閾值從6.1 mmol/l降至5.6 mmol/l,而世界衛生組織(WHO)建議的閾值仍維持在6.1 mmol/l。及早發現和醫治 高血壓患者的糖尿病,能降低其罹患心血管病的風險。循 證地制定適用於本地病人的空腹血糖異常數值,將有助善 用診斷糖尿病的資源。 目的:研究正在基層醫療接受治療高血壓的華裔病人,比較以ADA和WHO的空腹血糖異常標準預測和診斷糖尿病, 而分別推算其陽性預測值和篩查所需數量值。 對象和設計:在2013年1月至6月期間,為兩所普通科門 診的高血壓患者, 按ADA指引篩查出空腹血糖異常的 病人, 並安排他們接受標準的75g口服葡萄糖耐量試驗(OGTT)。如餐後2小時血糖值 ≥ 11.1 mmol/l,會重複進行OGTT,並檢測HbA1c水平。如在首次OGTT時的空腹血糖值已經≥ 7mmol/l,則僅需進行空腹血糖和HbA1c檢測。 主要測量內容:分別按照ADA和WHO的空腹血糖異常標準,推算以OGTT確診糖尿所得的陽性預測值和篩查所需 數量值。並研究空腹血糖異常患者與糖尿病相關的危險 因素。 結果:共有816名病人參與研究。在空腹血糖值5.6 – 6.0mmol/l和空腹血糖值6.1 – 6.9 mmol/l組別,分別有7.2%(45/624)和14.1%(27/192)的高血壓病人被診斷患有糖尿病。若按照ADA和WHO的空腹血糖異常標準診斷糖尿病,所得的陽性預測值分別為8.8% 和14.1%;而相應的糖尿病篩查所需數量值分別為13.87和7.11。研究同時發現,年齡愈大(OR 1.03,95% CI 1.00-1.05,p=0.046)、高密度脂蛋白水平愈低(OR 0.42,95% CI 0.20-0.89,p=0.023)、空腹血糖異常為6.1 – 6.9 mmol/l(OR 2.13,95% CI 1.24-3.66,p=0.006)以及服用β受體阻滯劑(OR 2.43,95% CI 1.45-4.06,p=0.001)均為具有統計學上顯著意義的糖尿病危險因素。 結論:採用ADA診斷標準的較低空腹血糖異常閾值診斷,華裔高血壓患者的糖尿病的陽性預測值將明顯降低。雖然我們未能確定以較低的空腹血糖異常閾值為高血壓患者篩查糖尿病是否合符成本效益,但會建議對已出現相關危險因素的患者進行篩查。 關鍵詞:空腹血糖異常,診斷標準,糖尿病,華裔高血壓 患者,基層醫療 lntroduction What is Impaired Fasting Glucose? Impaired fasting glucose (IFG) is a condition in which the fasting blood glucose level is consistently elevated above what is considered normal levels; however, it is not high enough for the patient to be diagnosed as having diabetes mellitus (DM). Impaired Glucose tolerance Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) is defined as having two-hour glucose levels of 7.8 to 11.0mmol/l on the 75-gram oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT).1 IFG is associated with insulin resistance and increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, although of lesser risk than IGT. IFG can progress to type 2 DM if lifestyle modifications are not made. The Portland study In a Portland study in 2007 involving 5,452 patients, 8.1% of subjects, whose initial abnormal fasting glucose (FG) was 5.6 - 6.0mmol/l, and 24.3% of subjects whose initial abnormal FG was 6.1 - 6.9mmol/l, developed diabetes within a mean of 41.4 months and 29.0 months respectively.2 The following risk factors were identified to be associated with the development of diabetes: advanced age, male gender, family history of diabetes in first degree relatives, physical inactivity, smoking, history of gestational diabetes, overweight or obesity, low high density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C), high low density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C), high triglyceride level, high blood pressure, being on thiazide or thiazide-like diuretics, beta-blockers and statins.3-5 In 2003 The ADA in 2003 lowered its threshold of definition for IFG from 6.1mmol/l to 5.6mmol/l basing on the evidence that diabetes prediction might be optimised at a lower threshold. It would also increase the homology of patients with IFG and those with IGT in terms of prevalence and predictive power for progression to DM.1,6 Studies showed that the new IFG threshold would increase the sensitivity to diagnose DM but the risk of developing DM in the group of patients with FG 5.6-6.0mmo/l was actually not high. The Hoorn study In the Hoorn study, the 6-year incidence of diabetes, as determined by a follow-up OGTT, was 5% in those with FG < 5.6mmol/l, 14% in the category 5.6–6.0mmol/l, and 44% in the category 6.1–6.9mmol/l.7 The D.E.S.I.R. study In the DESIR study, the incidence of DM per 1,000 person-years for the categories of FG < 5.6, 5.6–6.0, and 6.1–6.9mmol/l were 1.8, 5.7 and 43.2 in men and 0.7, 6.2 and 54.7 in women respectively.8 The Singapore study Also, in the Singapore Impaired Glucose Tolerance Follow-up Study, the 8-year incidence of diabetes was 2, 22, and 55% for the categories of FG < 5.6, 5.6–6.0, and 6.1–6.9 mmol/l respectively.9 The World Health Organization The WHO still recommends the cut-off point at 6.1mmol/l in the latest update of diagnostic criteria of diabetes in 2006.10 Diabetes Mellitus Diabetes mellitus is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in Hong Kong. The prevalence ranges from 2% in people aged less than 35 years to more than 20% in those older than 65 years.13 According to the statistics from Department of Health, it claimed about 20,500 in-patient discharges and deaths in all hospitals in 2012.14 Diabetes was the tenth commonest cause of deaths in Hong Kong in 2012 though the true number of deaths from diabetes was possibly higher since many deaths could be attributed to its late complications.14 Studies showed that early identification of IGT and diabetes could allow prompt management and hence reduce the incidence of diabetes and diabetes related morbidity and mortality.1,3,4,15 The ADA criteria or the WHO criteria Locally, there is no published guideline in Hong Kong regarding whether the ADA or WHO diagnostic criteria should be adopted. It was observed that different doctors would adopt different diagnostic criteria in our local practice. Using the lowered cut-off value for IFG would likely increase the number of patients diagnosed with IGT and diabetes and hence early intervention could be provided. However, the extra cost and associated psychological burden to the patients after being labeled IFG may not justify the benefit, which was suggested in a Japanese study.5 By lowering the diagnostic threshold for IFG from 6.1 to 5.6mmol/l, there would be a two to five fold increase in patients diagnosed with IFG.16 Also OGTT, the test recommended for patients with IFG to further diagnose IGT and diabetes, is comparatively complicated to use in daily clinical practice.17-18 The resulted substantial increase in number of IFG patients requiring OGTT would certainly cause an impact on the workload in an already busy public primary care clinic. Essential hypertension is an insulin-resistant state.19 Diabetes together with hypertension increases the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.20 The early detection of diabetes among hypertensive patients was emphasised in international guidelines, which suggested the screening for diabetes at time of hypertension diagnosis and repeating the diabetes screening annually.21-22 Hypertension is the most prevalent chronic disease in the Hospital Authority (HA) General Out-patient Clinics (GOPC) in Hong Kong. According to the data from HA Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System (CDARS), there were around 490,000 patients with hypertension having regular follow up in GOPC in 2011. This study was therefore designed to determine the positive predictive value (PPV) and the number needed to screen of the ADA’s definition of IFG to predict and diagnose diabetes mellitus in Chinese hypertensive patients in the Hong Kong primary care setting. The objectives of the study were to find out how many extra patients with diabetes would be diagnosed after lowering the cut-off level of IFG from 6.1 to 5.6mmol/l. We compared the positive predictive value (PPV) of ADA’s IFG criteria and number needed to screen for the diagnosis of diabetes with the WHO’s IFG criteria in the study population. The study would also identify the associated risk factors of diabetes in those patients with IFG. Methodology Study design This is a cross-sectional study. A cross-sectional study was chosen because the study aimed to find the prevalence of IFG, IGT and DM in the hypertensive patients within the studied period. The study was conducted in two public GOPC which are Family Medicine training centers. In the studied GOPC, FG was used for diabetes screening for hypertensive patients at time of diagnosis of hypertension and then annually. OGTT would be performed if patients were found to have impaired FG. All Chinese hypertensive patients with IFG according to the ADA criteria (FG level between 5.6 to 6.9mmol/l) detected via their latest annual blood test and being followed up in the two participating clinics from 1st January 2013 to 30th June 2013 were included in the study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were shown as below. Inclusion criteria: 1. All Chinese hypertensive patients with FG level 5.6-6.9mmol/l as their latest annual blood test and who were being followed up in the two participating clinics within the study period. Exclusion criteria:

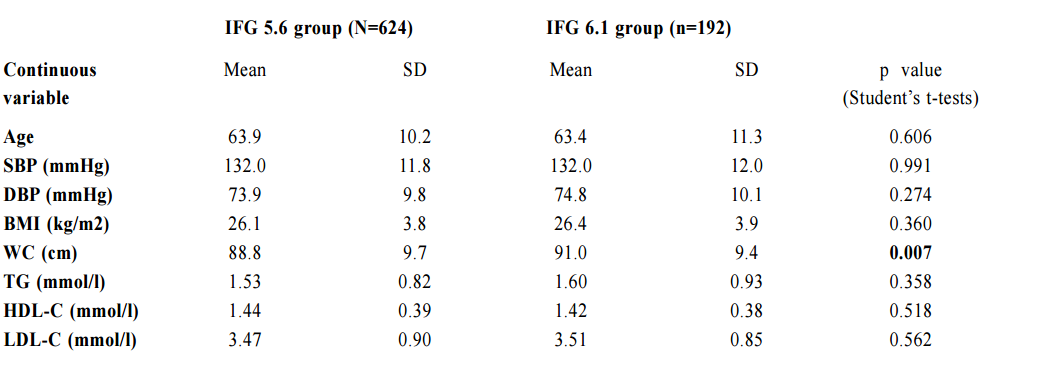

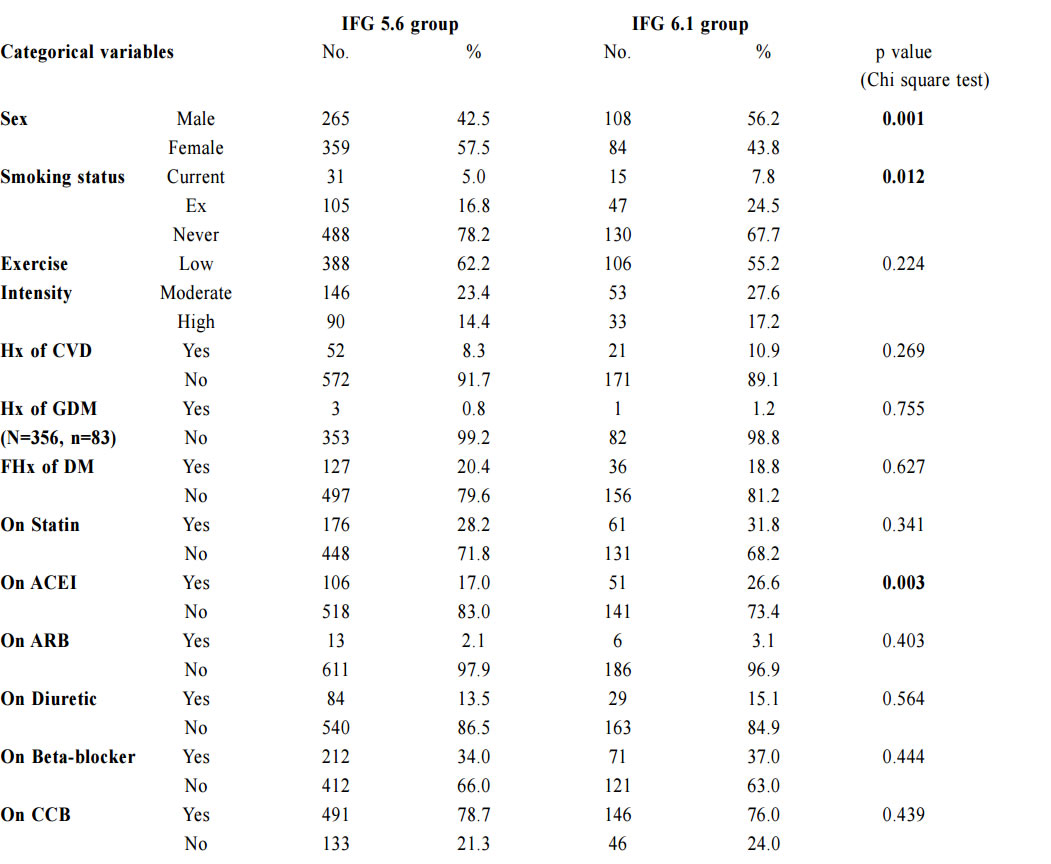

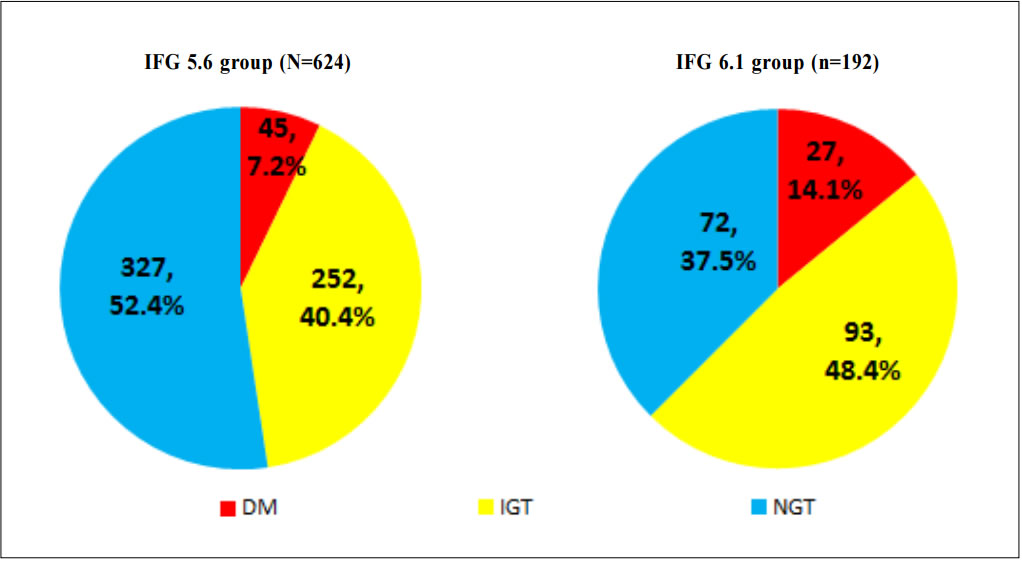

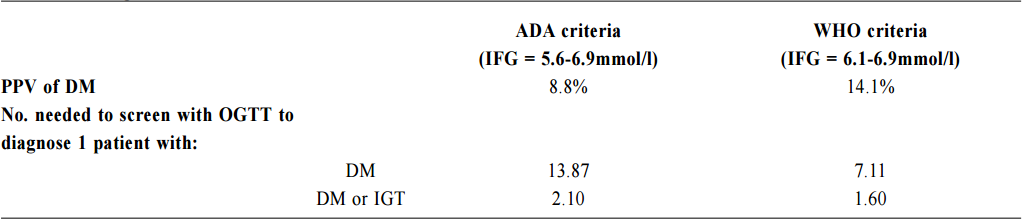

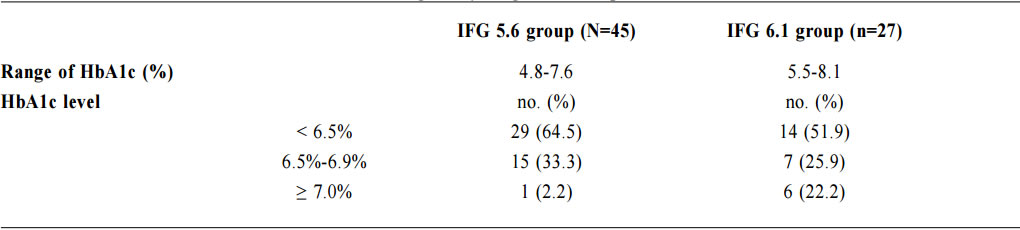

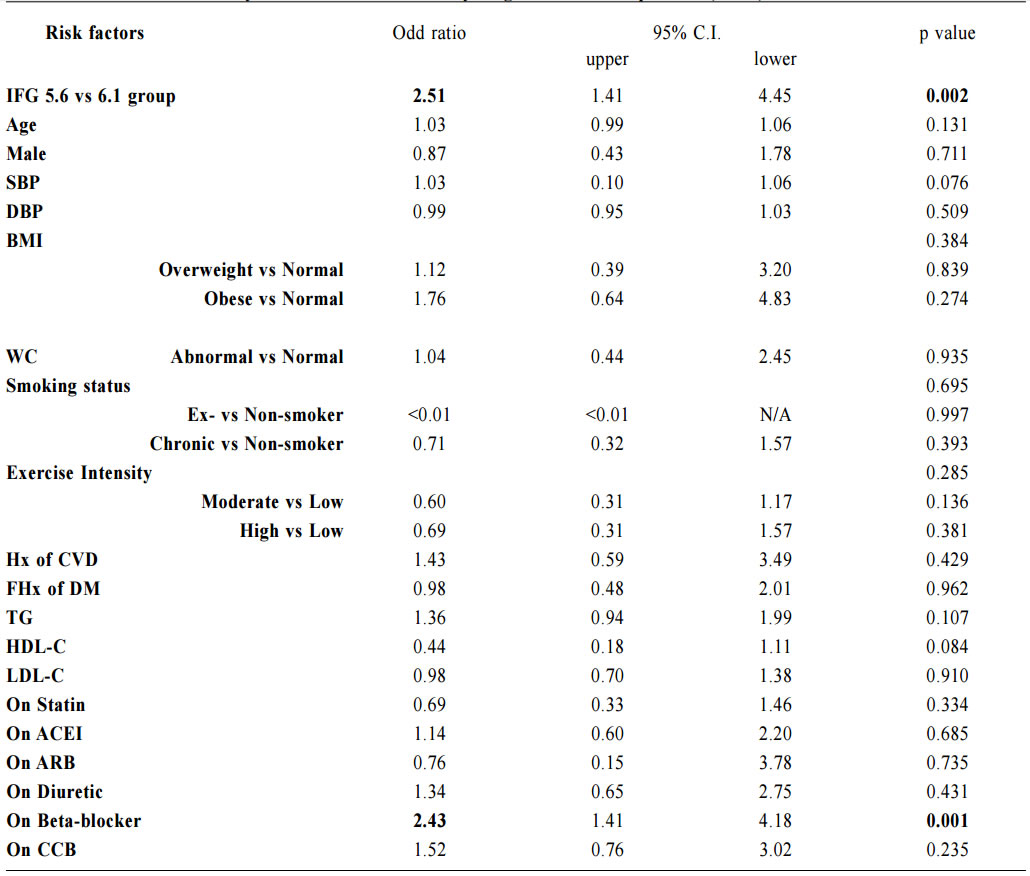

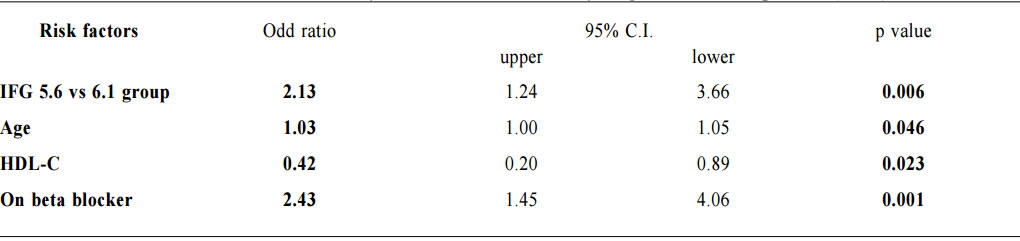

1. Non-Chinese ethnic patients The sampling frame would be able to include all the eligible subjects being followed up in the two participating clinics since the maximum duration of follow-up in the clinics was 16 weeks. Eligible subjects would be recruited consecutively during the study period until the calculated sample size was reached. Procedure Patients attending regular follow-up of their hypertension during the study period and fulfilling the criteria would undergo a standard 75g OGTT within 2 weeks. If the 2-hours plasma glucose level (2hrPG) was ≥ 11.1mmol/l, patients would be called back for follow up with OGTT repeated and HbA1c checked within 2 weeks. If the fasting glucose of the first OGTT was already ≥ 7mmol/l, then only blood tests for fasting glucose and HbA1c would be performed. The study process is summarised in Chart 1. The attending doctors helped to identify and collect the consultation notes of the eligible patients for further data analysis. During consultation, the patients’ risk factors for diabetes were identified by the attending doctors using a preset template. A seminar was conducted to explain the workflow to all the participating clinic doctors. Self-reported physical activity was classified into three categories: “low - almost completely inactive”; “moderate - some physical activity but less than 150 minutes of moderate intensity exercise per week”; or “high - equal to or more than 150 minutes of moderate intensity exercise per week”.23 Patients’ height (to the nearest cm), weight (to the nearest Kg), waist circumference (to the nearest cm) and blood pressure (the latest) were measured. Obesity and overweight were defined as body-mass index (BMI) more than or equal to 25kg/m2 and from 23 to 24.9kg/ m2 respectively. Waist circumferences of more than or equal to 90cm and 80cm were defined to be abnormal for male and female patients respectively.24 The patients’ latest lipid profile (HDL-C, LDL-C and triglyceride levels) was recorded. For patients who were on lipid lowering medication, the pre-treatment values were recorded. The types of anti-hypertensives currently being taken by the patients, if any, were recorded. DM was diagnosed according to the latest ADA and WHO guidelines. A positive result should be confirmed by a repeat of the above methods on a different day.12, 25 The computerised medical records of the subjects were reviewed and all data were documented in a spreadsheet for further data analysis. Sample size calculation The prevalence of diabetes in patients with hypertension and IFG according to the ADA criteria in our locality was unknown. An Italian study showed that 5.3% of IFG patients defined by FG of 5.6- 6.9mmol/l (ADA criteria) had diabetes.16 On the other hand, the DECODA study group showed that 18.9% of Asian people with IFG defined by a FG of 6.1–6.9mmol/l (WHO criteria) had diabetes. 26 With the lowering of the IFG cut-off to 5.6mmol/l, the prevalence of diabetes would be expected lower. A pilot study was therefore carried out in one of the participating clinics to estimate the prevalence of diabetes in our subjects. 20 consecutive eligible patients were recruited from 1st October 2012 to 31st October 2012.The prevalence of diabetes was found to be 15%. By using an online sample size calculator with the assumptions o f 2.5% precision, 15% prevalence and infinite population size, the estimated sample size was at least 784 in order to achieve 95% confidence interval.27 Chart 1: Flow chart of study process  FG=fasting glucose; DM=diabetes mellitus; IGT=impaired glucose tolerance; OGTT=oral glucose tolerance test Outcomes Primary outcomes were the positive predictive value (PPV) for the diagnosis of diabetes and the number needed to screen according to the ADA and WHO diagnostic criteria of IFG for diabetes testing with OGTT. Secondary outcome was the risk factors associated with diabetes in patients with IFG. Statistical Analysis All subjects would be grouped into IFG 5.6 group (patients with FG level from 5.6 to 6.0mmol/l) and IFG 6.1 group (patients with FG level from 6.1 to 6.9mmol/) for data analysis. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software (version 21.0). All continuous variables would be presented as means +/- standard deviation and compared with Student’s t-test. Categorical variables would be presented as percentages and compared with Chi-square test. Percentages of patients with normal glucose tolerance (NGT), impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and diabetes (DM) was calculated for patients in both IFG 5.6 group and IFG 6.1 group. The positive predictive value (PPV) for the diagnosis of diabetes in patients with IFG was calculated using both the ADA and WHO criteria. The corresponding number of IFG patients needed to screen with OGTT to diagnose one patient with diabetes and abnormal glucose tolerance (diabetes or IGT) was also calculated. Logistic regression was used to assess the risk factors associated with the presence of diabetes in patients with IFG. A 2-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Results Study population There were 18 patients excluded due to refusal of OGTT resulting in 816 subjects recruited in the study. The mean age of the subjects was 63.8. Clinical characteristics of the patients were shown in Table 1. Among the subjects, 624 (76.5%) had FG levels from 5.6 to 6.0mmol/l (IFG 5.6 group) and 192 (23.5%) had FG levels from 6.1 to 6.9mmol/l (IFG 6.1 group). Compared with patients in IFG 5.6 group, IFG 6.1 group had more proportion of male patients (42.5% vs 56.2%) and patients on ACEI (17.0% vs 26.6%), less proportion of never smoker (78.2% vs 67.7%) and higher mean waist circumference (88.8cm vs 91.0cm). The remaining characteristics were comparable in both groups. The proportion of patients diagnosed with NGT, IGT and DM in both IFG 5.6 group and IFG 6.1 group is shown in Chart 2. The PPV of diabetes using ADA and WHO IFG diagnostic criteria were 8.8% and 14.1% respectively. When using ADA IFG diagnostic criteria, the number of IFG patients needed to screen with OGTT to diagnose one patient with DM and abnormal glucose tolerance (DM or IGT) were 13.87 and 2.10 respectively. If WHO’s IFG diagnostic criteria was used, the number of IFG patients needed to screen with OGTT to diagnose one patient with DM and abnormal glucose tolerance (DM or IGT) were 7.11 and 1.60 respectively. (Table 2) The distribution of HbA1c levels among the newly diagnosed DM patients is shown in Table 3. In the IFG 6.1 group, 22.2% (6/27) of patients had HbA1c greater than or equal to 7% while in the IFG 5.6 group, only 2.2% (1/45) of patients had HbA1c greater than or equal to 7%. Logistic regression was used to determine any significant risk factors associated with diabetes in all newly diagnosed DM patients. (Table 4) There were only four patients with known history of gestational diabetes (GDM) and all of them were not diagnosed with diabetes. Since most of the other female patients were not tested or unknown for GDM during pregnancy, GDM was excluded in the analysis. Being in IFG 6.1 group and being on beta-blockers were significant risk factors with an odd ratio (OR) 2.51 (95% confidence interval 1.41-4.45, p=0.002) and OR 2.43 (95% confidence interval 1.41-4.18, p=0.001) respectively. Reduced model was achieved by backward selection of variables according to their Wald statistics. (Table 5) In the reduced model, being in IFG 6.1 group (OR 2.13, 95% confidence interval 1.24-3.66, p=0.006), increase in age (OR 1.03, 95% confidence interval 1.00-1.05, p=0.046), lower HDL-C (OR 0.42, 95% confidence interval 0.20-0.89, p=0.023), and being on beta-blockers (OR 2.43, 95% confidence interval 1.45-4.06, p=0.001) were found to be risk factors for diabetes in the population. Discussion The biochemical definition of IFG is important both for screening policies and in the detection of ‘at risk’ groups for the early diagnosis of diabetes. In this study of Chinese hypertensive patients, lowering the FG cut-off level for defining IFG from 6.1 to 5.6mmol/l resulted in 624 more patients, or about a 4.25 (816/192) fold increase in the number of patients being diagnosed IFG, which was consistent with the findings of other studies. 16 Moreover, 45 more patients with diabetes and 252 more patients with IGT were diagnosed in the study period. Lowering the cut-off of IFG would lead to an earlier diagnosis of IGT and diabetes of some patients which would allow early interventions to reduce the incidence of diabetes and diabetic complications respectively. However, the results showed that this would increase the number of screening test i.e. OGTT performed to about 4 folds and the PPV of diabetes with IFG would decrease from 14.1% to 8.8%. On the other hand, among the extra 45 patients diagnosed with diabetes, 35.5% (16/45) of patients had HbA1c levels higher than 6.5%. These patients might require drug treatment to achieve a better diabetes control. Table 1: Demographic, anthropometric and biochemical characteristics of patients in IFG 5.6 group and IFG 6.1 group Chart 2: Proportion of patients diagnosed with NGT, IGT and DM in patients in IFG 5.6 group and IFG 6.1 group Table 2: PPV of diabetes and the no. needed to screen with OGTT to diagnose DM according to ADA and WHO IFG diagnostic criteria Table 3: The distribution of HbA1c levels among newly diagnosed DM patients Table 4: Multivariate analysis of risk factors in newly diagnosed diabetes patients (N=72) Table 5: Reduced model-multivariate analysis of risk factors in newly diagnosed diabetes patients (N=72)

For the newly diagnosed diabetes patients, increase in age (OR 1.03), lower HDL-C level (OR 0.42), were found to be risk factors for diabetes as shown in previous studies. 28-29 Being on beta-blockers was also a significant risk factor (OR 2.43) for diabetes and the result was supported by another study.30 Therefore, as suggested by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence guideline, beta-blockers should not be used as first-line anti-hypertensive in treatment of hypertension unless there are other compelling indications. 22 Some other known risk factors for diabetes such as obesity were not statistically significant in this study. The reason might be due to the relative small population of diabetic patients having these risk factors. If the WHO IFG criteria were used, with the annual FG screening continuously done for these hypertensive patients, patients with diabetes would likely be diagnosed at some later time. However, the duration of delay and the incidence of serious diabetic complications accountable by the delay are not known. Further studies would be needed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of lowering the IFG cut-off for diabetes testing in Chinese hypertensive patients. Meanwhile, it would be reasonable to do screening for Chinese hypertensive patients with a lower IFG cut-off if they had significant risk factors including being on beta-blockers, older age and with a low HDL-C level. The ADA and WHO included HbA1c more than or equal to 6.5% as a diagnostic criterion for diabetes in 2010 and 2011 respectively. However, it was observed in our study that more than half of patients with diabetes (43/72, 59.7%) would be missed if only HbA1c level was used to screen patients with IFG. Further studies may be needed to evaluate the most appropriate cut off value of HbA1c for the diagnosis of diabetes in Chinese hypertensive patients. Limitations We acknowledge some limitations in our study. Firstly, the subjects in this study were recruited from two primary care clinics, limiting the generalisability of our results to the whole local population though our results were comparable to other international studies. Secondly, the sample size of newly diagnosed diabetic patients was small and the significance of some risk factors for diabetes might be underestimated. Conclusion By adopting the ADA diagnostic criteria for IFG, the positive predictive value of DM in Chinese hypertensive patients would be decreased significantly while the number needed to screen for diabetes and abnormal glucose tolerance would be nearly doubled. Among those newly diagnosed with diabetes, increase in age, lower HDL-C level and being on beta-blockers were associated factors. Although we are not certain about the cost-effectiveness to screen for diabetes in all Chinese hypertensive patients with a lower IFG cut-off value, screening in those with associated risk factors is recommended. Ming-lam Tsang, FHKAM (Family Medicine), FHKCFP, FRACGP Correspondence to: Dr Ming-lam Tsang, 99 Po Lam Road North, Tseung Kwan O, New Territories, Hong Kong SAR, China. E-mail: tml518@ha.org.hk

References

|

|