|

December 2017, Volume 39, No. 4

|

Update Article

|

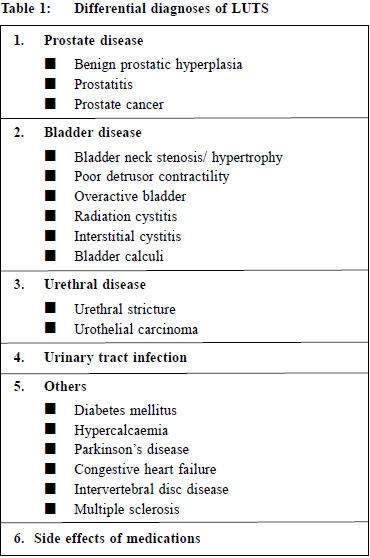

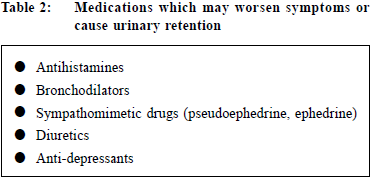

A review on the management and pharmacological treatments of benign prostatic hyperplasia in primary careKai-Lim Chow 周啟廉,Pang-Fai Chan 陳鵬飛,David VK Chao 周偉強 HK Pract 2017;39:116-125 Summary In men, the most common cause of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) is benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Bothersome LUTS can occur in up to 30% of men older than 65 years. LUTS can considerably reduce the quality of life of men and may indicate serious pathology of the urogenital tract. Family physicians should be able to differentiate different causes of LUTS in men and provide appropriate treatment and refer to urologists when indicated. The standard pharmacological therapy for BPH is using an alphablocker. Many patients may remain stable after being prescribed with alpha-blockers. Surgical intervention is an alternative treatment for patients who failed pharmacological therapy or have other BPH-related complications. 摘要 良性前列腺增生(BPH)是男性下尿路症狀(LUTS)最常見的原因。高達百分之三十的六十五歲以上男性患有使人困擾的LUTS。LUTS不但大大降低男性的生活質量,並且可能提示生殖泌尿道有嚴重的疾病。家庭醫生應該能夠鑒別診斷引發LUTS的各種不同原因,提供適當的治療,需要時將病人轉介給泌尿科醫生。BPH的標準藥物治療方案是使用α-阻滯劑。許多患者在服用α-阻滯劑後可以症狀保持穩定 。如果藥物治療無效或有其他BPH相關併發症,手術治療則是患者的另一種選擇。 IntroductionBPH is a histologic diagnosis that refers to the proliferation of smooth muscle and epithelial cells within the prostatic transition zone. The term ‘benign prostatic enlargement’ is more correctly used to describe prostatic enlargement.1 However, in common practice, the terms are used interchangeably. Possible causes of LUTS include abnormalities or abnormal function of the prostate, urethra, urinary bladder and sphincters. Urinary tract infection (UTI) and other medical causes can also present as LUTS.2 Table 1 shows the differential diagnoses of LUTS. In men, the most common cause of LUTS is BPH. The prevalence of BPH increases with age (~20% in 40-years-old men and 90% in 70-yearsold men).3 DiagnosisHistoryLUTS include voiding symptoms (weak or intermittent urinary stream, straining, hesitancy, terminal dribbling, and incomplete emptying), storage or irritative symptoms (urgency, frequency, urgency incontinence, and nocturia) and post-micturition symptoms (terminal dribbling). Patients with BPH usually have voiding, storage and post-micturition symptoms while patients with overactivity of bladder usually present with mainly storage symptoms.4 Symptoms severity of BPH can be assessed by International Prostate Symptoms Score (IPSS). It is a validated method for assessment of symptoms and quality of life in patients with BPH.2,5 A medical history is necessary to identify or to rule out those medical diseases that may also cause LUTS. For example, diabetes can cause polyuria which may be presented as urinary frequency; heart failure and sleep apnoea can cause nocturia, Parkinson’s disease and diabetes can cause LUTS due to autonomic neuropathy. In addition, review of current medications including over-the-counter and herbal medications is important.6 Table 2 shows the medications which may worsen LUTS or cause urinary retention. Past medical history like urological procedure which may increase the risk of urethral stricture and family history of prostate cancer are also important. Lifestyle habits, emotional and psychological factors should be reviewed.7

Physical ExaminationPhysical examination of suprapubic area, external genitalia ,perineum and lower limbs should be performed. Urethral discharge, meatal stenosis, phimosis and penile cancer must be excluded.2 Digital rectal examination (DRE) should be performed to evaluate the anal sphincter tone, the size, consistency, shape of the prostate gland and to detect any abnormalities suggestive of prostate cancer. Although DRE is the simplest way to assess prostate volume, the correlation to prostate volume is poor.8

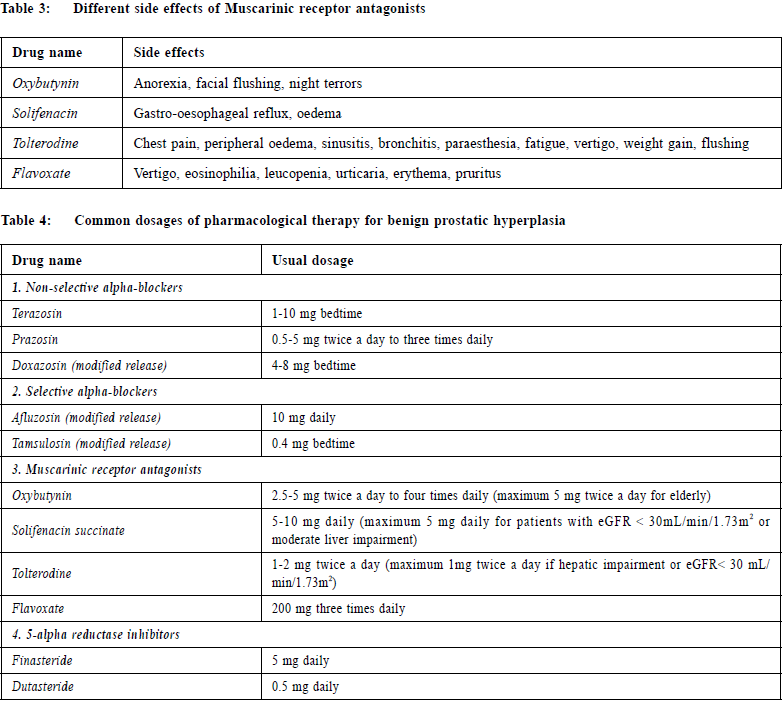

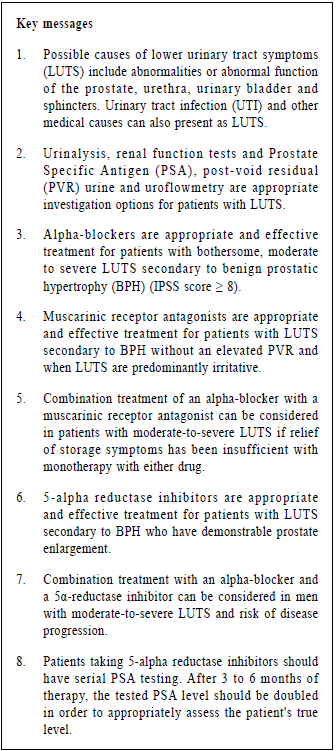

InvestigationUrinalysisUrinalysis is recommended in most guidelines in the management of patients with LUTS to identify important conditions, such as UTI, microscopic haematuria and diabetes mellitus.1,2,4,9,10 Renal function testsRenal function may be assessed by serum creatinine or estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). One study reported that 11% of men with LUTS had renal insufficiency.11 Renal function tests should be offered to patients with LUTS if patients are suspected of renal impairment (for example, the man has a palpable bladder, nocturnal enuresis, recurrent UTI or a history of renal stones).4 Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA)According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline 2010, LUTS information, advice and time for decision should be offered to patients with LUTS suggestive of bladder outlet obstruction secondary to BPH or with abnormal findings on DRE or with concern about prostate cancer if they wish to have PSA testing.4 The American Urological Association (AUA) recommends that PSA should be measured in men who have at least a 10-year life expectancy and who would be a candidate for prostate cancer treatment.1 Post-void residual urinePost-void residual (PVR) urine can be assessed by transabdominal ultrasound. This is important for the treatment of patients using muscarinic receptor antagonist. It was recommended that measurement of PVR in male LUTS should be a routine part of the assessment.2 UroflowmetryUrinary flow rate assessment is a widely used non-invasive urodynamic test. It was recommended that uroflowmetry may be performed in the initial assessment of male LUTS and should be performed prior to any treatment.2 ManagementConservative managementAccording to the AUA standard, watchful waiting is recommended for patients with mild symptoms (IPSS score < 8).1 In one study, approximately 85% of men with mild LUTS were stable on watchful waiting at one year.12 Symptom distress may be reduced with some behavioural and dietary modifications such as reduction of fluid intake in evening, avoidance of intake of caffeine or alcohol, use of relaxed, double-voiding techniques and bladder retraining.13,14,15,16 Support from a urology nurse may be beneficial. Regular monitoring with history, physical examination and the IPSS score can assess the treatment response and changing symptoms. Increasing symptoms or bothersome scores are reasonable indications to consider pharmacological therapy.17 Pharmacological treatmentsAlpha-blockerAccording to the AUA standard, alpha-blockers are appropriate and effective treatment alternatives for patients with bothersome, moderate to severe LUTS secondary to BPH (IPSS score ≥ 8).1 Alpha-blockers aim to inhibit the effect of endogenously released noradrenaline on smooth muscle cells in the prostate and therefore reduce prostate tone.18 A study demonstrated that both selective alpha-blockers (Alfuzosin and Tamsulosin) and non-selective alpha-blockers (Doxazosin, Terazosin and Prazosin) have similar efficacy.19 Selective alpha-blockers may have fewer systemic side effects and are indicated in patients who cannot tolerate non-selective alpha-blockers. The most frequent adverse events of alpha-blockers are dizziness and orthostatic hypotension. Vasodilating effects are more pronounced with Doxazosin and Terazosin, and are less common for Alfuzosin and Tamsulosin.20 Therapy with non-selective alpha-blockers should be initiated with a low dose and then be titrated upward. Side effects, particularly orthostatic hypotension, should be explained to patients and patients’ blood pressure should be monitored. Other potential adverse effects of alpha-blockers include drowsiness, hypotension, syncope, asthenia, depression, headache, dry mouth, gastro-intestinal disturbances, edema, blurred vision, intra-operative floppy iris syndrome (especially with Tamsulosin), rhinitis, erectile disorders (including priapism), tachycardia, palpitations, hypersensitivity reactions including rash, pruritus and angioedema.21 Due to the potential adverse effect of intra-operative floppy iris syndrome and a lot of patients with BPH may have co-existing cataract, the AUA guideline recommended that patients should be asked about planned cataract surgery when alpha-blocker therapy is offered. Patients with planned cataract surgery are recommended to avoid the initiation of alpha-blockers until their cataract surgery is completed. However, for patients already taking an alpha-blocker for treatment of BPH, there is insufficient research evidence to recommend withholding or discontinuing alpha blockers to mitigate the risk. Table 4 shows the common dosage of alpha-blockers. Muscarinic receptor antagonistsMuscarinic receptor antagonists block the neurotransmitter acetylcholine in the central and the peripheral nervous system. This class of medication reduces the effects mediated by acetylcholine on its receptors in bladder neurons through competitive inhibition. There are five muscarinic subclasses (M1 through M5) of cholinergic receptors in the human bladder muscle, the majority are subtypes M2 and M3. While M2 receptors predominate, M3 receptors are primarily responsible for bladder contraction.22 According to the AUA standard, muscarinic receptor antagonists are appropriate and effective treatment alternatives for the management of LUTS secondary to BPH in men without an elevated PVR and when LUTS are predominantly irritative.1 Also according to the European Association of Urology, combination treatment of an alpha-blocker with a muscarinic receptor antagonist is recommended in patients with moderate-to-severe LUTS if relief of storage symptoms has been insufficient with monotherapy with either drug.2 Theoretically muscarinic receptor antagonists might decrease bladder strength, and hence might be associated with PVR urinary retention. AUA suggested that baseline PVR urine should be assessed prior to the initiation of muscarinic receptor antagonists and these agents should be used with caution in patients with a PVR greater than 250 to 300 mL.1 There is no clear evidence that one muscarinic receptor antagonist is better than another.23,24,25,26 However they may have different anticholinergic side effects (See Table 3).21 Examples of muscarinic receptor antagonists include Oxybutynin, Solifenacin, Tolterodine and Flavoxate. Table 4 shows the common dosage of muscarinic receptor antagonists. The potential adverse effects are dry mouth, gastrointestinal disturbances, taste disturbances, blurred vision, dry eyes, drowsiness, dizziness, fatigue, difficulty in micturition, urinary retention, palpitation, skin reactions, headache, diarrhoea, angioedema, arrhythmias, tachycardia, restlessness, disorientation, hallucination, convulsion, reduce sweating leading to heat sensations and risk of precipitating angle-closure glaucoma.21

5-alpha reductase inhibitors 5-alpha reductase inhibitors increase intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate, thus reducing smooth muscle tone of the detrusor, prostate and urethra. They might also alter the reflex pathways in the spinal cord and neurotransmission in the urethra, prostate, or bladder.27 Chronic treatment seems to increase blood perfusion and oxygenation in the lower urinary tract.28 It could reduce chronic inflammation in the prostate and bladder.29 Moverover, it leads to a reduction in the overall androgenic growth stimulus in the prostate, an increase in apoptosis and atrophy and ultimately a shrinkage of the organ.1 There are two 5-alpha reductase inhibitors available namely Finasteride and Dutasteride. No data directly compare these two inhibitors for their differences in clinical efficacy. AUA guidelines stated that 5-alpha reductase inhibitors are appropriate and effective treatment alternatives for men with LUTS secondary to BPH who have demonstrable prostate enlargement. Also European Association of Urology recommended combination treatment with an alpha-blocker and a 5α-reductase inhibitor in men with moderate-to-severe LUTS and risk of disease progression. In different studies, various thresholds have been proposed for the definition of prostate enlargement (25, 30 or 40 mL). Serum PSA has been recommended as a proxy for prostate size larger than 40 mL.2 A study suggested that the approximate age-specific criteria for detecting men with prostate glands exceeding 40 mL are PSA > 1.6 ng/ mL, > 2.0 ng/mL, and > 2.3 ng/mL for men with BPH in their 50s, 60s, and 70s, respectively.30 5-alpha reductase inhibitors can be used to prevent progression of LUTS secondary to BPH and to reduce the risk of urinary retention and future prostate-related surgery.1 Adverse effects include decreased in libido, ejaculatory and erectile dysfunction, breast tenderness and enlargement.21 Two trials have found a higher incidence of high-grade prostatic cancers in patients receiving 5-alpha reductase inhibitors.31,32 Although no causal relationship with highgrade prostatic cancers has been proven, patients taking 5-alpha reductase inhibitors should have serial PSA testing.2 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors typically decrease a patient's PSA by about 50%.33 Because of delayed prostatic response to 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors, after 3 to 6 months of therapy, the tested PSA level should be doubled in order to appropriately assess the patient's true level.34 Table 4 shows the common dosage of 5-alpha reductase inhibitors. Follow-upAccording to NICE guideline, patients should be reviewed to assess symptoms, the effect of the drugs on the patient's quality of life and to ask about any adverse effects from treatment. For men prescribed with alphablockers or muscarinic receptor antagonists, reviews should be done more frequently for dosage titration until symptoms are stable.4 ReferralOnce treatment for BPH has been initiated, a referral to a urologist would be indicated if there is failure of urinary symptom control despite optimisation of pharmacological therapy, suspicion of prostate cancer from a prostate exam, elevation in serum PSA levels, gross or persistent microscopic hematuria, sterile pyuria, recurrent UTI, urinary calculus, hydronephrosis, meatus stenosis, urinary retention and renal insufficiency or renal failure due to obstruction.35 ConclusionBPH is common in men and their incidence increases with age. With an aging population, it is important for family physicians to have a good understanding of the non-operative management of BPH. Pharmacological therapy can be initiated in the primary care setting and many patients may remain stable without the need for further treatment. The standard therapy for managing a patient with BPH is initiating an alpha-blocker. Muscarinic receptor antagonists may be useful in patients with BPH and significant irritative or storage symptoms despite the use of alpha-blockers. For patients with larger prostates, the addition of a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor may be considered. Patients should be referred for urologist assessment if indicated.

Kai-Lim Chow,MSc (Epidemiology and Biostatistics) (CUHK), FHKAM (Family Medicine), FHKCFP,

FRACGP

Correspondence to: Dr Kai-Lim Chow, Department of Family Medicine and Primary

Health Care, United Christian Hospital, 130 Hip Wo Street,

Kwun Tong, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR.

E-mail: chowkl2@ha.org.hk

References

|

|