|

December 2017, Volume 39, No. 4

|

Original Article

|

White coat effect can be an illusion that may possibly result in sub-optimal blood pressure control?Stephen CW Chou 周俊永,Chris KV Chau 周家偉,Kin-Kwan Yeung 楊健群,Jenny HL Wang 王華力, Alfred SK Kwong 鄺兆基,Wendy WS Tsui 徐詠詩 HK Pract 2017;39:129-143 SummaryObjectives: To study how accurate is the discrepancy between the home blood pressure and clinic blood pressure readings being attributed to white coat effect in hypertensive patients. Design: Cross-sectional study. Subjects: From Februar y 2015 to July 2015, we recruited hypertensive patients, who had recent three clinic visits showing elevated clinic blood pressure (BP), from the general outpatient clinics within one Hospital Authority cluster for our study. They should have had normal Home Blood Pressure Monitoring (HBPM) results and did not receive any hypertensive medication adjustment. Main outcomes: 1) The proportion of sub-optimal blood pressure control (SOBP) patients in suspected ‘White Coat Effect’ (WCE) patients. 2) The associated factors of the SOBP groups among suspected WCE patients.

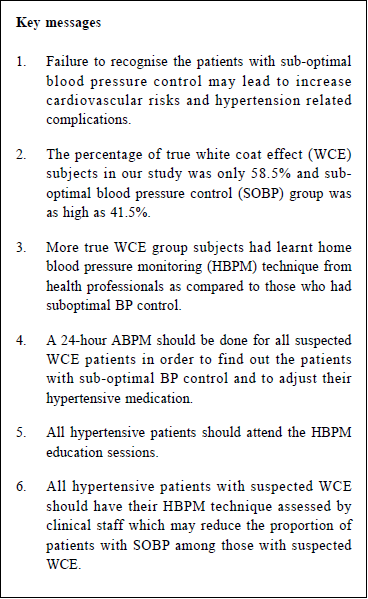

Methods and Resul ts: Among 112 pat ient s we recruited for the study, 106 patients completed the study. They also had undergone 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) and each completed a self-administered questionnaire. After analysing the 24-hour ABPM study results, the percentage of true WCE in our study was only 58.5% and SOBP group was as high as 41.5%. Higher proportion of subjects (53.2%; p = 0.01) with true WCE was found in the groups of patients who had learnt HBPM technique from health professionals as compared to those (46.8%) who had not. There were longer histories of HBPM in the SOBP group (6.9±4.9 years) compared to those in the true WCE group (5.1±4.1 years; p=0.04). The clinic systolic blood pressure (SBP) of the subjects was slightly higher in the SOBP group (158±13 mmHg) than in the true WCE group (154±9 mmHg; p=0.04). Conclusion: In this study, substantial amount (> 40%) of patients labelled as having WCE were actually having suboptimal BP control. Therefore, 24-hour ABPM should be offered to patients who were suspected to have WCE in order to guarantee a better blood pressure control for these patients. We suggest that all patients with hypertension should attend the HBPM technique classes to have an accurate measurement of their BP. The longer the history of the home blood pressure measurement or the higher the SBP, the more likely the patients had suboptimal BP control than having WCE. Patients with HBPM should be assessed by nurses on their BP measurement technique that may reduce the proportion of suboptimal BP control in patients with suspected WCE. Keywords:Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, hypertension, clinic blood pressure, white coat effect 摘要目的:研究當高血壓病人的臨床血壓讀數和在家血壓讀數出現差異時,將其原因視為「白袍效應」的準確性。 設計: 橫斷面研究。 對象:在醫院管理局一個聯網的普通科門診於2015年2月至7月期間,對在最近三次覆診時,均出現臨床血壓超標的高血壓病人進行研究。而他們的在家血壓讀數(HBPM)均屬正常,亦無調較任何降壓藥物劑量。 主要結果:1. 血壓控制欠佳(SOBP)病人在懷疑呈現「白袍效應」(WCE)者中的比例。2. 在懷疑呈現WCE者中,與SOBP組別相關的因素。 方法與結果: 在112位乎合條件的高血壓病人,106人完成研究。他們均接受過2 4 小時隨攜式血壓紀錄監測(ABPM),並自行完成一份問卷調查。經過分析24小時ABPM的紀錄後,有高達41.5%的病人被確定為血壓控制欠佳,而只有58.5%的屬真正WCE。在真正WCE群組中,46.8%從未學過HBPM,相比之下,而較多病人(53.2%;p = 0.01) 曾向護理人員學習HBPM方法。SOBP組別(6.9±4.9年)比真正WC E組別(5.1±4.1年; p = 0.04)有較長久的HBPM時間。此外,SOBP組別的臨床時收縮壓(SBP)水平(158±13 mmHg)比真正WCE組別的(154±9mmHg;p = 0.04)稍高。 結論: 本研究顯示為數頗多(>40%)會被視為WCE的病人,實際上是血壓控制欠佳。因此,為使懷疑WCE的病人能保證有較佳的血壓控制,應向他們提供24小時的ABPM。我們建議所有高血壓病人都應正式地學習HBPM方法,以能準確地量度自己的血壓。過去在家量度血壓的年期愈長,或SBP愈高者,他們更有可能出現血壓控制欠佳,而非WCE。護士應審視病人進行HBPM時的量度血壓方法,這樣或許可以減少血壓控制欠佳者在懷疑WCE病人群組中的部份。 關鍵字:隨攜式血壓紀錄監測,高血壓,臨床血壓,白袍效應 IntroductionHypertension (HT) is a well-known common chronic disease among the adult population of Hong Kong. Twenty–seven percent of the Hong Kong population aged 15 or above had increased blood pressure in the recent Government reports.1 This is the second commonest reason for consultation in primary care.2 Hypertension is one of the major risk factors of cardiovascular disease. Many research studies confirmed the harmful effects of uncontrolled hypertension and the benefit of optimal treatment for hypertension.3 In our daily primary care practice, we have seen some patients had unsatisfactory clinic blood pressure readings but their home blood pressure readings were normal. There was an assumption that the observed discrepancy between the clinic blood pressure reading and the home blood pressure reading was due to the White Coat Effect (WCE). White Coat Hypertension (WCH), due to the white coat effect, in general is defined as hypertension happened in patients when they have high BP measurement obtained in healthcare setting but not so at home.4 To the best of our knowledge, the definition of WCE was not well standardised although a difference of 20 mmHg in systolic pressure is usually used.5 Attending doctors who attributed the discrepancy in the blood pressure readings to the WCE, for a long time tended not to adjust hypertensive medications. White coat hypertension is an important clinical problem in general practice.6, 7 Failure to recognise WCE may lead to over-treatment or over-dosing and inappropriate use of medications and investigations. Although ABPM is a key procedure to diagnose WCH 8, 9, performing ABPM in all of the suspected WCH patients is costly. So there were many research studies which attempted to find out the clinical characteristics of subjects who could be susceptible to the development of WCH.10-12 Some overseas studies13, 14 suggested that blood pressure readings, gender, body mass index, smoking status and small left ventricular mass may be the predictors of WCH. However, the findings were not consistent. Although there have been many studies on WCH, to the best of our knowledge, there was no formal study on the area of WCE; that is, to study the subjects with known hypertension (HT) and have already started taking hypertensive medications. It is important to know the proportion of sub-optimal blood pressure control patients in suspected WCH patients. Failure to recognise the patients with sub-optimal blood pressure control may lead to increase cardiovascular risks and HT related complications. We also want to know if the suspected predictors of WCE can be applied to the WCH patients. Ideally, all the suspected WCE patients need to have 24-hour ABPM to confirm the diagnosis; however, it is costly in terms of manpower, expertise and time. If predictors related to WCE can be identified, then we can prioritise our patients better and the resources can be used more cost-effectively. From a pilot review in one of the general outpatient clinics in our cluster, there were about 6% of hypertensive patients labelled as having WCE. From time to time, however, there have been concerns over the reliability of this assumption in clinical assessment and the monitoring of their blood pressure measurements with such measurement discrepancy. If the WCE does not in fact exist in these patients and if no adjustment of hypertensive medication was made, then we would render them having increased risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular complications. Therefore, we would like to assess how common WCE is in our patients. In our pilot study, records of the ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) between September 2011 and December 2012 were reviewed. Thirty-four hypertensive patients, with either normal or borderline home BP but high clinic BP, were referred for ABPM. Twenty-seven patients labelled as having white coat effect (79%) were in fact having suboptimal BP control and only three had true White Coat Effect. In a local study by Tam et al published in 2007, which recruited patients in the primary care clinics of Department of Health, showed that 28.2% of their study population was having white coat hypertension.15 In another local study by Chiang et al, published in 2013 the ambulatory blood pressure monitoring reports of 359 patients were analysed.16 Eighteen percent was confirmed to have white coat hypertension. In this study, 202 patients were in the group of “White coat hypertension or White coat phenomenon”, 56% was diagnosed to have WCE. However, there was no separate data about the hypertensive patients, who were already on hypertensive medications with WCE. Compared to home blood pressure measurement, it is known that 24-hour ABPM has better correlation with cardiovascular outcomes and end organ damage.17, 18 In fact, ABPM was advocated as the gold standard for diagnosis of hypertension in the NICE 2011 Hypertension Guideline.19 In our clinic, patients with suspected WCE according to case doctors’ clinical judgement and protocol may undergo the 24-hour ABPM for further assessment. However, the utilisation rate of 24-hour ABPM is not high because the case doctors usually accept the diagnosis of WCE in patients with discrepant home blood pressure and clinic blood pressure readings. ObjectivesThe aim of the study is to improve our management of hypertensive patients with discrepant home and clinic BP readings by providing more accurate assessment and optimal treatment for these patients. The objectives of this study are to investigate the prevalence and risk factors of patients who are actually having suboptimal high blood pressure while they are labelled as having WCE in public primary care setting in Hong Kong. MethodThis was a cross-sectional study conducted in 4 general out-patient clinics in our cluster. Hypertensive patients with marked discrepancy between home BP reading and clinic BP reading (over 20mmHg difference in systolic or 10mmHg in diastolic pressure higher in the clinic readings than the home readings) in three consecutive clinic visits were recruited as subjects in the study. The home blood pressure results could be the written records or verbal reports provided by patients. Inclusion criteria

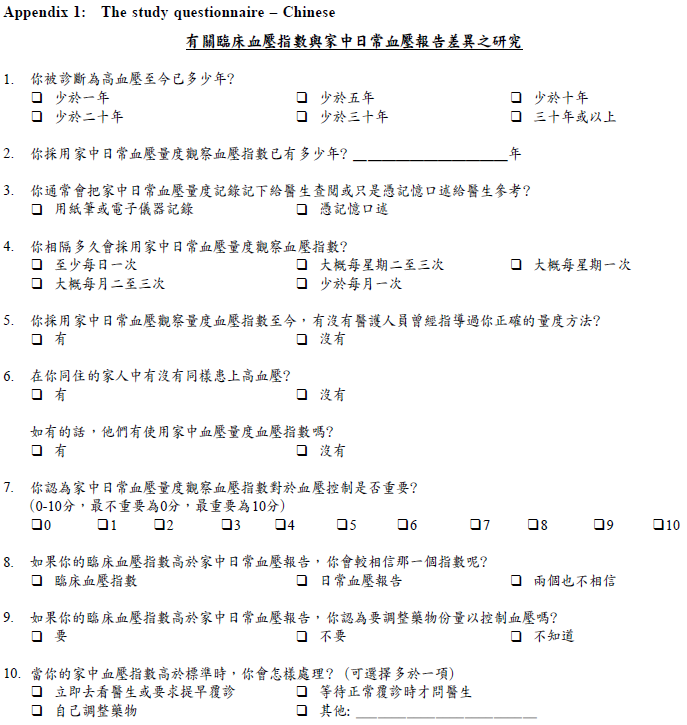

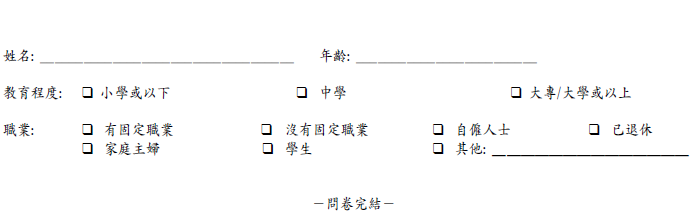

We had reviewed the clinical records in one of our clinics for 2 weeks in October 2014, and there were about 6% of hypertensive patients fulfilling the criteria. We designed a questionnaire for the subjects to obtain the information about their demographic data and their usual practice in home blood pressure monitoring. The questionnaire contained 10 questions written in Chinese (Appendix 1). A field test for acceptability and understanding of the questionnaire was performed and 10 patients were invited to fill in the questionnaire. After they finished the questionnaire, our co-investigators would explain the questions to the subjects in order to make sure they understood the questions correctly. Results showed that the questions in the questionnaire were well accepted and understood by the subjects. We had applied for the ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong / Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (HKU / HA HKW IRB) and the IRB certificate was obtained on 9th of January 2015. Since we have no idea of the true proportion of SOBP in hypertensive patients who were on medications and having WCE, we assume the hypothetical proportion to be 50% and we expect 65% in sample proportion to detect the difference. We used the equation20 N>{u √[P x (1-P)] + v √[Po x (1 –Po)]}2/ (P – Po)2 , in which P = proportion in sample = 0.65; Po = null hypothesis value = 0.5; u = one sided percentage point of normal distribution, taking power = 80%, u = 0.84; v = percentage point of 2 sided significant level, taking p value = 5%, v = 1.96. After computing, the sample size is > 85. Assuming the response rate was about 90%, then the minimum number of subjects required is around 94. Therefore, we recruited around 100 subjects in our study. From the period of February 2015 to July 2015, medical officers in the clinic were alerted by our nurses when patients had high BP in that visit. If medical officers found that the patients had a discrepancies between home BP reading and clinic BP reading (more than 20mmHg in systolic or 10mmHg in diastolic blood pressure) and the clinic BP reading was elevated (systolic blood pressure more than 140mmHg or diastolic blood pressure more than 90mmHg), clinical notes of the subjects would be reviewed by the investigator. Patients who had not adjusted hypertensive medications in the past three clinic visits were recruited. The clinic BP result was obtained by taking the average value of the recent three clinic BP readings in clinical notes. Written consents for the study would be obtained from patients. Information about the procedure and their rights as participants in the study were explained to them by our co-investigators. Subjects recruited were arranged to have a 24-hour ABPM. 24-hour ABPM was arranged in the Risk Assessment and Management Programme (RAMP) Clinic. When the subjects attended RAMP Clinic on Day 1, they would get the ABPM machine and fill in the above questionnaire. If the subjects had any difficulty in filling in the questionnaire, the trained nurses in the RAMP Clinic would assist them. The subjects would attend RAMP Clinic again on Day 2 and return the ABPM machine to RAMP Clinic. The results of the ABPM would be sent to the incharge Associate Consultant of the RAMP Clinic who had been trained in the interpretation and analysis of ABPM results. After the reports were ready, the results of individuals would be used to compare with the previous diagnosis made on clinical assessment by the doctors. The reports and filled questionnaires would be kept in a locked cabinet. Data analysis was performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21. Descriptive information for each explanatory variable was derived. Association of each variable with white coat effect was assessed by t-test for continuous variables and Chi-squared test for categorical variables. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multiple regression analysis was used to assess the association and effect among different variables. The primary outcome of this study was to find out whether the discrepancy between home and clinic BP readings is really the “white coat effect” (WCE). We would also like to investigate the risk factors of having the suboptimal BP control other than white coat effect. The secondary outcome of this study was to compare the parameters between the hypertensive patients who really have “white coat effect” and those did not have WCE after investigation. Then we can have more understanding about the characteristics if any of these two groups of hypertensive patients for enhancing our management of their clinical conditions in the future.

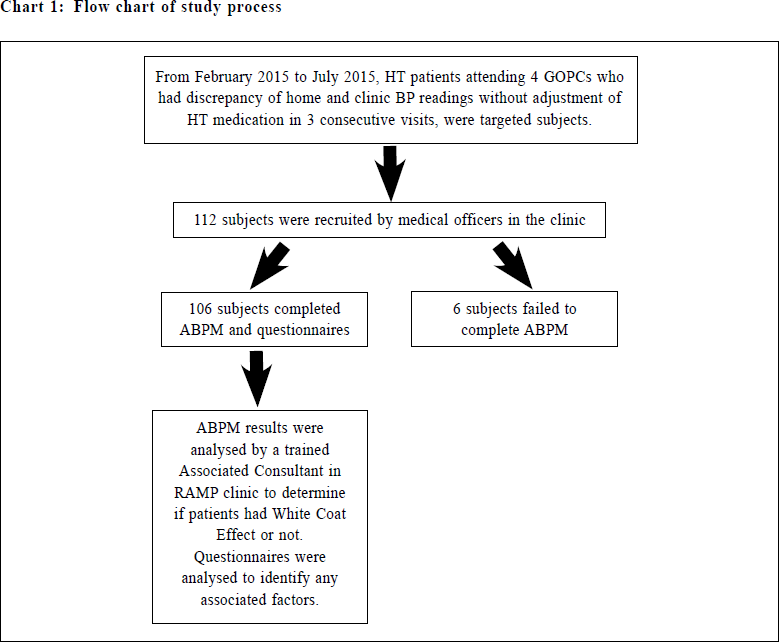

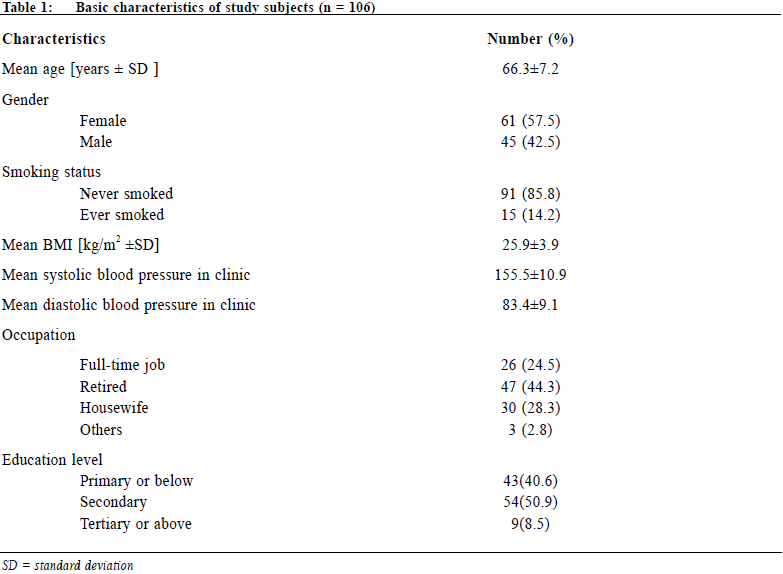

ResultsAnalysisFrom February 2015 to July 2015, we recruited 112 subjects for this study. Among them, 106 (94.6%) subjects successfully completed the ABPM study and finished the questionnaires. Six (5.4%) subjects failed to complete the ABPM study. Three of them refused to receive ABPM investigation, as they were too busy to come and get the ABPM machines. Another three subjects found it uncomfortable to have the machine fastened on their arms for frequent BP measurement. Some of them reported that the measurement disturbed their sleep. The discomfort was mainly experienced as a mild numbness on their hands for a short period of time after the measurement by the ABPM machines. They took off the machine prematurely and the data obtained was henceforth incomplete. These data was, therefore, not used in our final analysis. During the study period, there was no report of significant complications generated by the procedure. The mean age of subjects was 66.3±7.2 years, body mass index (BMI) 25.9±3.9 kg/m2, mean systolic blood pressure in clinic was 155.5±10.9 mmHg and mean diastolic blood pressure in clinic was 83.4±9.1 mmHg. All of them were either non-smokers (n=91; 85.8%) or ex-smoker (n = 15; 14.2%). There were no current smokers among the subjects. More than half of them (50.9%, 54/106) reached secondary school level and more than 40% (43/106) were at primary school level or below. Only nine (8.5%) subjects reached tertiary education level or above. Most of the subjects were either retired (n=47; 44.3%) or housewife (n= 30; 28.3%). Only 26 (24.5%) of the subjects had full-time job at the time of the study. (Table 1)

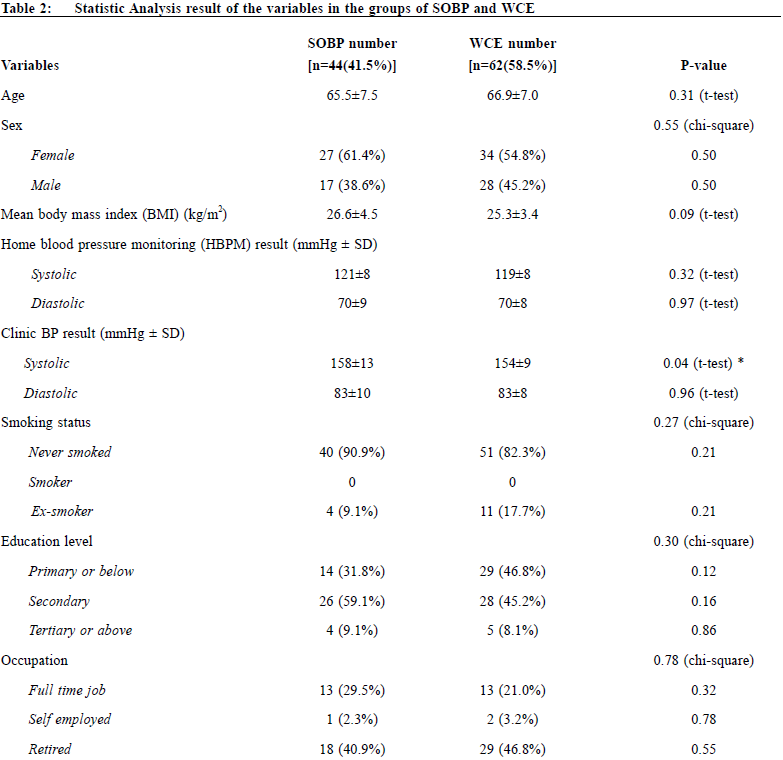

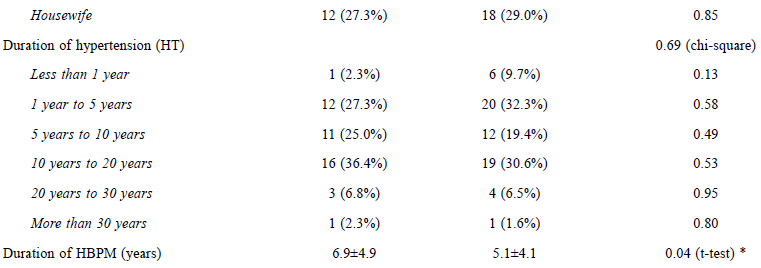

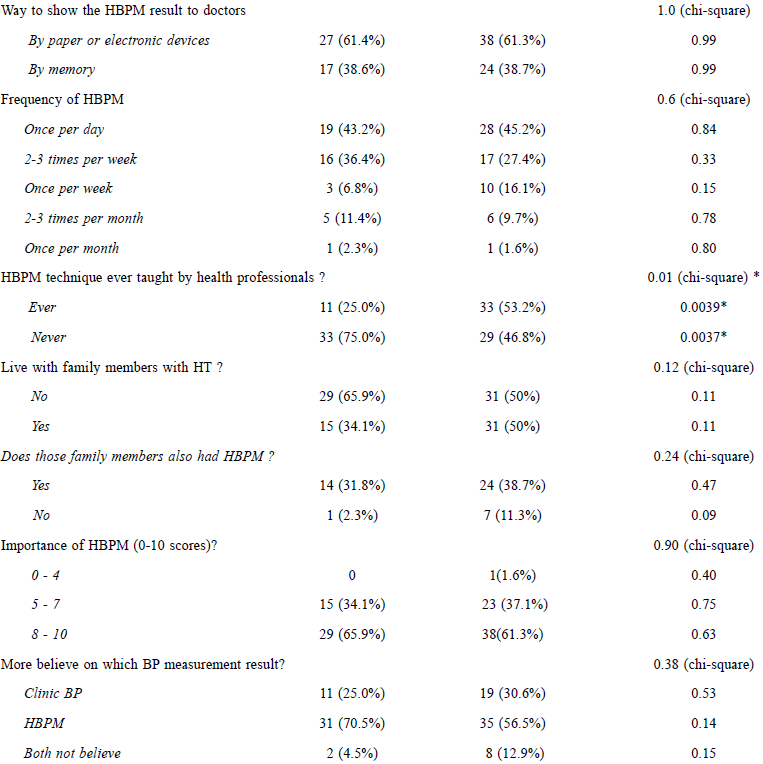

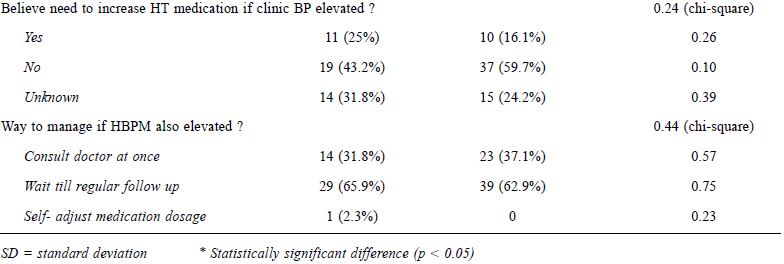

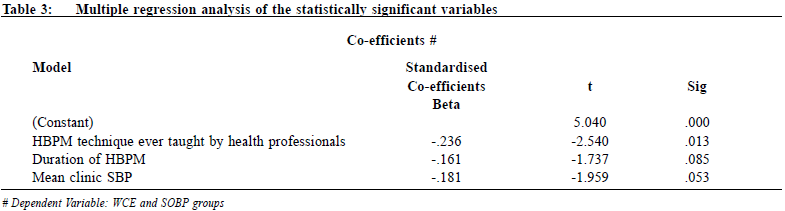

After analysis of the 24-hour ABPM study results, the percentage of white coat effect (WCE) in our study was 58.5% and that of the suboptimal blood pressure control (SOBP) group was 41.5%. Bivariate analysis was used to derive the corelation between different variables among the groups with WCE as well as SOBP group. (Table 2) There were more subjects with true WCE who had learnt the HPBM technique from health professionals and the result was statistically significant (p = 0.0039). There were more subjects in SOBP group with longer time experience of HBPM. The clinic SBP level was found higher in the SOBP group. Both of the variables just reached statistically significance (pe= 0.04). Multiple regression analysis was used to assess the association and effect among the above three variables and the result suggested that HBPM technique taught by health professionals was an important factor among them as compared to the other two variables. From the questionnaire, we knew that most subjects (n = 93; 87.6%) had HBPM more than once per week and they usually marked the HBPM results on paper or electronic devices (n = 65; 61.3%). Most of the subjects were living with family members who also had hypertension (n = 46; 43.4%). Among their hypertensive family members, 38 (82.6%) of them also had HBPM as well. Most of the subjects considered HBPM were important as 67 subjects (65.1%) gave more than 8 marks (minimum score 0 and maximum score 10) for it in the questionnaire. Most of the subjects believed in HBPM results more than clinic BP results (n = 66; 62.2%), so they thought that there was no need to increase their hypertension medication even though their clinic BP results were elevated (n = 56; 52.8%). Only 1 (0.9%) subject would adjust hypertensive medications by himself if he found his HBPM result elevated. All the above factors were found to be statistically insignificant.

DiscussionFrom our study, there were about 40% of the subjects belonging to the group of SOBP. If they were left untreated as they were considered as WCE patients by their case doctors then cardiovascular and hypertensive complication will increase. In other words, 40% of suspected WCE patients were found under-treatment which is an alarming result in our study. Since it is a local cluster study, we may not apply the result to the whole territory. We suggest having further studies in other clusters in order to have a broader view in the management of WCE patients. The predictors in WCH, like gender, body mass index and smoking status, were not statistical significantly related to the WCE subjects in our study. We also investigated whether other factors like age, occupation, education level, duration of HT, frequency of HBPM and living with other HT relatives could be the predictors of WCE, but they were all statistically insignificant. In this study, we found that the subjects who had previously been taught about the HBPM techniques by health professions, were more likely to be having true WCE. This reflects the importance of teaching the correct HBPM techniques to all HT patients. If the patients know the correct ways to use their own blood pressure machine, their HBPM results will be more reliable and discrepancy between their HBPM and clinic BP results could be less. We suggest that HT patients should attend the HBPM education session and, for the suspected WCE patients, clinical staff should check their self-HBPM techniques to ensure that their HBP readings are accurate. Although there was statistical significance in the relationship of duration of HBPM experience and SOBP group, it was found that the longer the HBPM experience the more likely to be having suboptimal BP control in the suspected WCE patients. It therefore was difficult to apply the duration of HBPM experience as one of the predictors for ruling out WCE. If the patients did not learn the proper HBPM techniques, patients with longer HBPM experience might lead to longer period of “normal” HBPM result presented to their case doctors. The false reassurance was in fact dangerous that might affect the decision of their case doctors on the appropriate medications and be more prone to offer suboptimal treatment of their SOBP. The clinic SBP results were statistically significant in suspected WCE subjects that the higher their clinic SBP, the more likely they were having sub-optimal BP control. However, the means of clinic SBP between the SOBP and WCE groups were very close (158±13 vs 154±9 mmHg). We suspected that subjects who had jotted down their HBPM results on paper or in electronic devices would be more prone to have WCE rather than having SOBP since they were more concerned about their BP readings. The results however showed that there was not much difference between the two groups. From the questionnaire, we found that most suspected WCE subjects believed that HBPM was important in their HT management. They believed more in the accuracy of HBPM results than their clinic BP results. However, as their HBPM technique might not have been properly assessed by health professionals, they might falsely believe that they were really having true WCE rather than sub-optimal control of BP.

In view of the importance of proper HBPM In view of the importance of proper HBPM techniques and the alarming results in the proportion of SOBP subjects in suspected WCE patients, we need to put more effort in teaching all our HT patients with correct HBPM techniques. We should refer all the suspected WCE patients for a 24-hour ABPM and to monitor their self-HBPM technique regularly if resources are available. LimitationsOur study was carried out in only one cluster in Hong Kong for a limited period of time. There was only one 24-hour ABPM machine available in our RAMP clinic for the study, so the proportion of the SOBP patients versus WCE patients in our study might not be able to represent the real situation in other clusters and to apply the findings to the whole Hong Kong population. With the limited resources, we could only arrange 5 patients to have 24-hour ABPM in our RAMP clinic in a week. Therefore only about 100 suspected WCE patients were recruited in our study. If more ABPM machines and more time were available, we could carry out a larger sample size study to investigate the proportion of SOBP patients versus WCE patients in our cluster and even in other clusters. Besides, more predictors of SOBP patients and WCE patients could be identified if a larger scale and more wide-spread study can be carried out in the future. The majority of our patients were from low income population. In our study, the education levels of most subjects were secondary school or below, and most of them were housewives or retired. It therefore might not reflect the real picture in Hong Kong. If the study could involve private clinics or private hospitals where patients with higher educational levels and working classes attended, the prevalence of the SOBP patients and WCE patients could be more representative of our Hong Kong population. ConclusionIn conclusion, if resource is available, a 24-hour ABPM should be done for all suspected WCE patients in order to find out the patients with sub-optimal BP control and to adjust their HT medication so that their cardiovascular risks, and HT complications can be lowered. All the HT patients should be recommended to attend the HBPM education sessions. All patients with WCE should have their HBPM techniques reviewed by clinical staff. AcknowledgementWe would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Chief of Service, Consultants and the Clinic In-charge Doctors in our cluster for their support on this study and the arrangement of the ABPM in our RAMP clinic. We would like to thank our RAMP clinic Associate Consultant for the interpretation of the ABPM results in our study and the Advanced Practice Nurse in our RAMP clinic for arranging the subjects to have ABPM.

Stephen CW Chou,MBChB (CUHK), FHKAM (Family Medicine), FHKCFP, FRACGP Correspondence to:Dr Stephen CW Chou, Sai Ying Pun General Outpatient Clinic, 1/F,

134 Queen’s Road West, Sai Ying Pun, Hong Kong SAR.

E-mail: choucw@ha.org.hk

References

|

|