|

March 2016, Volume 38, No. 1

|

Update Article

|

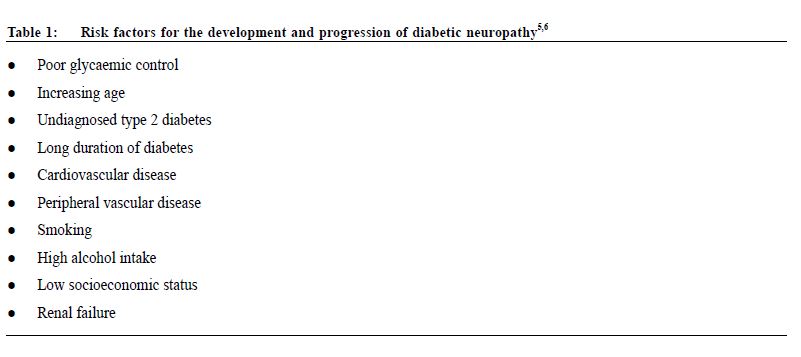

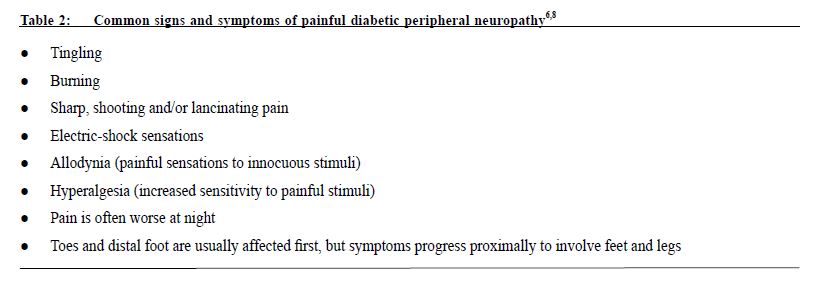

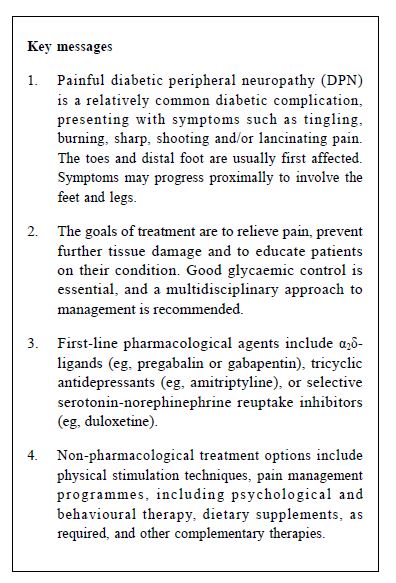

Multidisciplinary management of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: literature review and updated recommendationWY Ip 葉永玉,PP Chen 曾煥彬,Joseph MK Lam 藍明權,Gavin KW Lee 李家榮,WK Lee 李永堅,Carina CF Li 李靜芬,HW Leung 梁浩云,Vincent Mok 莫仲棠,TH Tsoi 蔡德康,CP Wong 王春波,Steven Wong 黃河山 HK Pract 2016;38:13-23 Summary The management of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) requires a multidisciplinary approach, encompas sing both pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment strategies. The Mul t idiscipl inar y Panel on Neuropathic Pain has publ ished recommendat ions on the management of painful DPN and provides here an update that emphasises the importance of good glycaemic control for all patients with diabetes, and includes newly published epidemiological studies and clinical evidence for the management of painful DPN. Based on published clinical evidence and international guidelines, first-line agents for DPN include α2δ-ligands, tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. If a reasonable trial of a first-line agent does not relieve pain effectively, combination therapy with or switching to another first-line agent should be considered. Tramadol can be considered as a second-line treatment option. 摘要 糖尿病性末梢神經病變引起的疼痛,需由不同學科的醫 療團隊以藥物及非藥物方式進行治療。跨學科研究神經 病變性疼痛小組在最近發表治療糖尿病性末梢神經病變 的建議時,強調所有糖尿病患者在控制血糖水平的重要 性,並引述最新處理糖尿病末梢神經病變性疼痛的流行 病學研究和臨床實證。據已發表的臨床實證和國際指 引,治療糖尿病性末梢神經病變的第一線藥物包括α2δ- 配體、三環類抗抑鬱藥和選擇性血清素及正腎上腺素再 吸收抑制劑。當第一線藥物未能有效紓緩痛楚時,可考 慮轉換另一種第一線藥物或同時使用兩種一線藥物;而 曲馬朵 (tramadol) 可作為第二線治療選擇。 lntroduction The Multidisciplinary Panel on Neuropathic Pain (MPNP) publishes evidence-based recommendations on the management of neuropathic pain. The MPNP aims to improve the awareness and understanding of neuropathic pain in Hong Kong via medical education activities and materials for physicians and the community. The panel held its inaugural meeting in December 2001 and includes specialists from a range of disciplines involved in treating neuropathic pain, namely anaesthesiology, geriatric medicine, neurology, neurosurgery, psychiatry, orthopaedics and rheumatology. Recommendations on the management of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) were first published in 20031, with an update in 2006.2 This present updated recommendation aims to help healthcare professionals to evaluate a patient’s condition and decide on a suitable treatment strategy. The recommendation is not intended to replace professional judgment in determining the appropriate management of individual patients. Prevalence, symptoms, pathophysiology, and burden of illness Globally, the prevalence of diabetes is increasing, particularly in Asia. The estimated prevalence of diabetes in East Asian countries ranges from 6 to 11%; in Hong Kong the prevalence is 9%.3 Diabetic neuropathy is a family of progressive degenerative disorders affecting the sensory, motor or autonomic peripheral nerves.4,5 Poor glycaemic control and chronic hyperglycaemia are believed to be responsible for peripheral nerve damage.6 In Chinese patients with DPN, changes in nerve conduction velocity and histopathology of peripheral nerves were shown to be positively correlated with duration of diabetes and overall blood glucose levels.7 Abnormalities in nerve growth factors, autoimmune disorders, ischaemia and hypoxia may also contribute to loss of nerve fibres. Key risk factors for the development and progression of diabetic neuropathy are presented in Table 1. Up to 50% of patients with long-standing diabetes develop some form of neuropathy.4,5,8 Common symptoms of painful DPN are listed in Table 2. The overall prevalence of sensory neuropathy in Hong Kong is estimated from registry data to be around 2%.9 While this figure is lower than estimates from other countries, the average disease duration of Hong Kong registry patients is only 5 years.

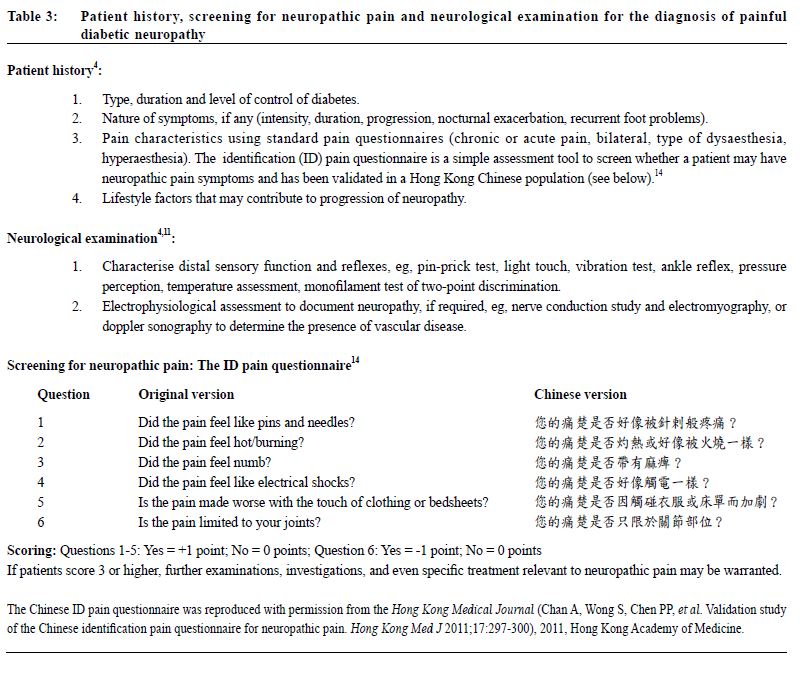

Distal symmetric polyneuropathy is the most common form of diabetic neuropathy, affecting around 40% of patients who have had diabetes for 25 years or longer.4 In a study conducted in China, 47% of 556 subjects with diabetes of more than 10 years’ duration were characterised as having diabetic neuropathy. Of these, 38% had mild pain, while 41% reported moderate and 11% severe pain.10 Diabetic polyneuropathies usually involve the peripheral nerves of the feet and legs and, in some cases, the hands and arms. Early symptoms include numbness, tingling, burning or pain, usually starting in the toes and spreading proximally.8 The condition also involves loss of reflexes, and loss of sensation which can lead to foot ulceration and even the need for amputation.8,11 Early diagnosis and management of at-risk patients might prevent at least half of all diabetes-related amputations.11 Painful DPN is associated with significant burden of illness. In the United States, an observational study of 112 subjects with painful DPN revealed that 44% suffered from sleep disturbance/insomnia, 41% had depressive symptoms and 36% had anxiety.12 Almost 80% of these subjects reported moderate to severe pain. Healthcare resource utilisation was high, and increased with greater pain severity. Indeed, healthcare resource utilisation and costs are higher in patients with painful DPN compared with those with diabetes alone, with the highest burden associated with severe painful DPN.13 Diagnosis Diagnosis of diabetic neuropathy is based on clinical symptomatology. Other underlying pathologies for neuropathy should be excluded (eg, vascular disease, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], vitamin B12 deficiency, hypothyroidism).4 Clinical features vary widely, and people with diabetic neuropathy may even be pain-free. However, the classic presentation of advanced polyneuropathy is distal wasting and weakness, absent tendon reflexes, and glove-and-stocking sensory loss and/or pain.8 Patients may also experience allodynia. Key points to consider in assessing patients for painful DPN are presented in Table 3.

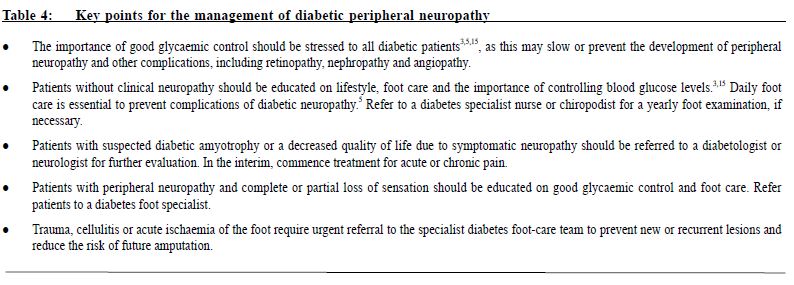

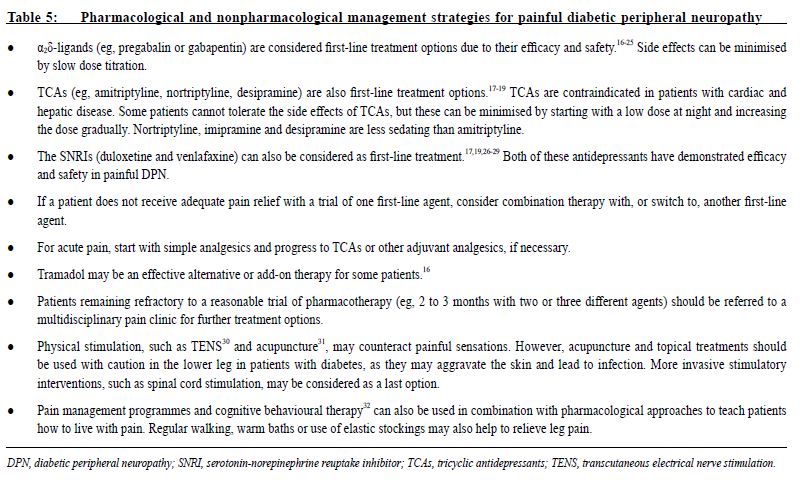

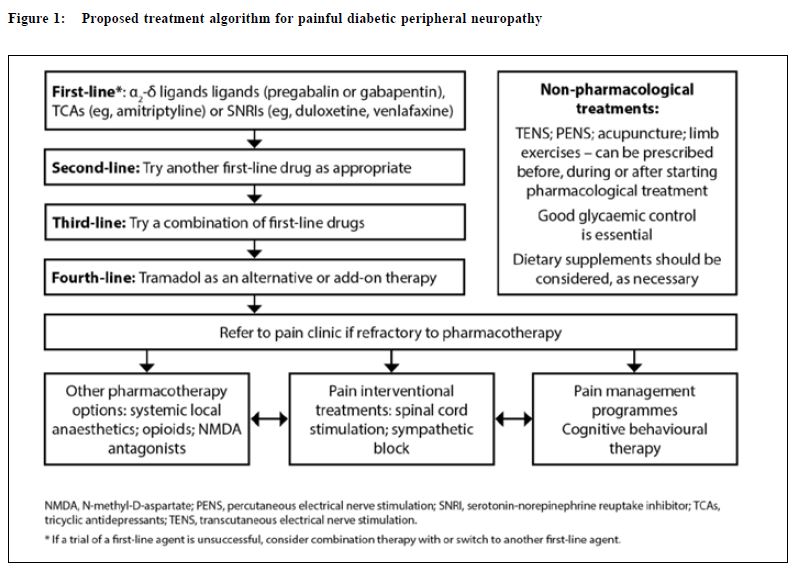

Management The goals of treatment for painful DPN are to relieve painful symptoms, prevent further tissue damage and educate patients. While a cure for painful DPN may not be available, deterioration of neurological condition and pain can be managed with good glycaemic control and pain management techniques.8 A summary of key points to consider in the management of DPN is presented in Table 4. This review provides a summary for family physicians outlining the importance of a multidisciplinary approach, whether they initiate treatment themselves or who refers to a specialist. Multidisciplinary management of painful DPN A number of international guidelines on pharmacological management of neuropathic pain (some of these are specifically on painful DPN) have been published in the past few years.16-19 These guidelines recommend α2δ-ligands (eg, pregabalin or gabapentin), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs; eg, amitriptyline) or selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs; eg, duloxetine, venlafaxine) as first-line treatment for painful DPN. The American Academy of Neurology recommends that pregabalin be given as first-line treatment for painful DPN, which is the only medication with Level A evidence.16 There is no particular preference among the first-line agents, the choice of which depends on physician’ experience and patient' tolerance as well as financial considerations. A multidisciplinary approach to management should be taken to maximise pain relief. Good glycaemic control is essential, and pharmacotherapy should be used in conjunction with physical and psychological therapy (Table 5). Pharmacological management The pharmacological treatments included in these recommendations are based on published clinical evidence from trials in patients with painful DPN and current clinical practice. PubMed was searched for clinical trials, review articles and treatment guidelines on peripheral diabetic neuropathy from the date of the last recommendation update (2006)2 until January 2015. Full prescribing information should be consulted before initiating drug therapy. Some drugs may not be approved for use in neuropathic pain syndromes. The proposed treatment algorithm for painful DPN is presented in Figure 1. The α2δ-ligands Pregabalin Pregabalin (300 and 600 mg/day) is effective in painful DPN and is associated with greater improvements in pain, mood, sleep disturbance and quality of life measures than placebo.20,21 Pain relief and improved sleep were observed from as early as one week in many patients, and were sustained throughout the study period.20 Recent randomised, placebo-controlled studies performed on patients with painful DPN in China (n=308) and in Japan (n=317) with pregabalin treatment over 8 and 14 weeks, respectively, were similarly associated with improved pain ratings and other clinical outcomes than placebo.23,24 Pregabalin was well tolerated, with dizziness and somnolence the most common adverse events; the adverse events were generally mild to moderate in severity.

A recently published meta-analysis involving nine trials (n=2,056) demonstrated pregabalin’s superiority over placebo in improving mean pain scores.33 Furthermore, 36% of pregabalin patients and 24% of placebo patients reported at least a 50% reduction in pain (relative risk [RR] 1.54; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.20−1.98; p=0.007). Sleep improvement was greater with pregabalin than placebo. While more pregabalin-treated patients experienced mild side effects, the drug was considered reasonably well tolerated. In older patients (≥ 65 years), pregabalin is an effective treatment option as it provides effective pain relief, comparable with that in younger patients, and has no known drug–drug interactions in a population in which polypharmacy is quite common.25 Add-on therapy with low-dose oxycodone (10 mg/day) did not provide any additional pain relief compared to pregabalin in patients with painful DPN.34 Gabapentin Gabapentin was the first oral drug therapy to be licensed for the management of painful DPN. In a large, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, gabapentin was associated with lower pain scores and significant improvements in a number of clinical outcomes, such as sleep interference, quality of life and “Clinician Global Impression of Change” (CGIC) scores, compared with placebo.22 Dizziness and somnolence were the only two adverse events that occurred significantly more frequently in gabapentin-treated patients. A gastro-retentive gabapentin (gabapentin-GR) formulation, requiring once-daily dosing, is effective and well tolerated in painful DPN.35 A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial randomised the patients (n=147) with symmetrical pain symptoms in distal extremities to gabapentin-GR, given once or twice-daily (titrated from 300 to 3,000 mg/day as a single evening dose or as a divided dose [1,200 mg morning/1,800 mg nocte]), or placebo. The reduction in average daily pain score was significantly greater with gabapentin-GR once-daily compared to the placebo (p=0.002); 34.8% of gabapentin-GR patients achieved ≥ 50% reduction in average pain score compared with 7.8% of placebo patients (p=0.001). Although numerically larger, the reduction in pain score with gabapentin-GR twice-daily was not significantly greater than the placebo. The incidence of dizziness and somnolence was also low. Tricyclic antidepressants Several clinical trials have shown that TCAs are effective in treating painful diabetic neuropathy. Although they are not licensed for this indication, some international guidelines continue to recommend TCAs as a first-line treatment option.17-19 Data from systematic reviews A systematic review of randomised, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants in DPN pooled data from eight studies using TCAs (amitriptyline, clomipramine, desipramine, imipramine and maprotiline) with a total of 283 patient episodes.36 The relative benefit of treatment was 1.9 (95% CI: 1.5−2.3) and the number-needed-to-treat (NNT) for one patient to achieve at least 50% reduction in pain was 3.5 (95% CI: 2.5−5.6). The incidence of adverse events is significantly greater with TCAs than placebo. For minor adverse events, the number-needed-to-harm (NNH) was 3.2 (95% CI: 2.3−5.2) and for major adverse effects (ie, those necessitating drug withdrawal), the NNH was 14 (95% CI: 8.5−38).36 Selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors Duloxetine The efficacy and safety of duloxetine in painful DPN has been demonstrated in several randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of 12 weeks’ duration.37-39 Duloxetine (60 or 120 mg/day) was associated with significantly better improvements in pain outcomes, and was well tolerated. A Cochrane review concluded that the evidence for duloxetine (60 and 120 mg/day) in treating pain in DPN is moderately strong.27 Pooled data on safety and tolerability of duloxetine from the 12-week (acute) studies and 52-week extension studies versus routine care has been published.28 A total of 1,139 patients participated in the acute studies and 867 in the extension studies. During the acute studies, significantly more treatment-emergent adverse events were reported with duloxetine than placebo (p=0.001), the most common of which were nausea and somnolence. In the extension phase,duloxetine was associated with modest changes in glycaemia compared with routine care. No disease progression was observed for neuropathy, nephropathy or retinopathy. Venlafaxine Venlafaxine was shown in a randomised controlled trial (n=244) to reduce baseline visual analogue pain intensity by 32% (75 mg) and 50% (150–225 mg; p<0.001 vs placebo) at six weeks.29 For the venlafaxine 150–225 mg regimen, the NNT for 50% pain intensity reduction was 4.5, which is similar to NNTs for TCAs and gabapentin.29 Desvenlafaxine Desvenlafaxine at 200 mg and 400 mg was shown in a randomised controlled trial to significantly change the numeric rating scale score (p<0.001 and p=0.027, respectively).40 The most common treatmentemergent adverse events were nausea and dizziness, but desvenlafaxine was generally well tolerated. Comparative efficacy of anticonvulsants and antidepressants A randomised, double-blind, cross-over clinical trial compared the efficacy and safety of pregabalin (75, 150 and 300 mg bid) and amitriptyline (10, 25 and 50 mg nocte) in 51 patients with DPN.41 Each treatment period was 5 weeks, with a 3-week washout period between treatments. While similar pain relief and improvements in other clinical outcomes were observed between the two treatments, fewer adverse events were reported with pregabalin (25%) than amitriptyline (65%). The optimal dose of pregabalin was 150 mg bid. In a double-blind, cross-over trial, 58 patients with DPN were randomised to receive duloxetine (20–60 mg nocte) or amitriptyline (10–50 mg nocte) for 6 weeks with a 2-week washout period between treatments.42 Significant improvements in pain from baseline were observed with both treatments (p<0.001), and other efficacy outcomes were similar between the groups. While the total number of adverse events reported in each group was similar, more patients reported dry mouth with amitriptyline (55%) when compared to duloxetine (24%; p<0.01). An open-label, randomised study compared duloxetine monotherapy (n=138), pregabalin monotherapy (n=134) or combination of duloxetine and gabapentin (n=135) in patients with inadequate response to gabapentin.43 After 12 weeks of treatment, the mean change in pain rating was -2.6 for duloxetine and -2.1 for pregabalin. This demonstrates the non-inferiority of duloxetine to pregabalin (treatment difference 0.49; 95% CI -0.05 to 1.04; p=0.08). The non-inferiority comparison between duloxetine monotherapy and duloxetine plus gabapentin, a secondary objective, on the differences between endpoint mean changes in daily pain ratings was also met. The total number of adverse events reported did not differ between groups. In a randomised, controlled trial of pregabalin (75 mg bid), carbamazepine (200 mg bid) and venlafaxine (150 mg/d) in patients with painful DPN (n=257), the mean visual analogue scale scores at baseline were 82.3, 74.5 and 74.5, respectively, with significant reductions to 33.4, 39.6 and 46.6, respectively, after 35 days of treatment.44 While significant reductions were observed in all groups (p=0.0001), pregabalin was associated with greater reductions in pain than carbamazepine and venlafaxine. In all groups there were improvements in sleep, mood and work interference outcomes. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies including antidepressants (amitriptyline, duloxetine and venlafaxine) and anticonvulsants (pregabalin, gabapentin and valproate) found that duloxetine, gabapentin, pregabalin and venlafaxine were superior to placebo (odds ratios 2.12, 3.98, 2.78 and 4.43, respectively; insufficient data on valproate were available for analysis).45 The ranking order for efficacy was gabapentin, venlafaxine, pregabalin, duloxetine/gabapentin combination, duloxetine, amitriptyline and placebo. For safety, the ranking order was placebo, gabapentin, pregabalin, venlafaxine, duloxetine/gabapentin, duloxetine and amitriptyline. μ-Opioid receptor agonists Tramadol Tramadol (at an average daily dose of 210 mg) was shown in a randomised controlled trial (n=131) to be significantly more effective at 6 weeks in relieving pain (p<0.001) and improving both physical (p=0.02) and social functioning (p=0.04) than placebo.46 No benefits were seen in sleep disturbance. In a 6-month extension of this study, mean pain relief scores were well maintained.47 A randomised, open-label trial compared the efficacy and safety of a combination of tramadol/acetaminophen (37.5/325 mg titrated to tid dosing and up to eight tablets/ day, as required) versus gabapentin (300 mg titrated to 3,600 mg/day, as required) for 6 weeks.48 The study included 163 patients with painful symmetric neuropathy in the lower limbs and mean pain-intensity score ≥4 on a numeric rating scale. The mean reductions in pain intensity at the final visit were similar between the groups (-3.1 ± 2.0 for tramadol/ acetaminophen; -2.7 ± 2.1 for gabapentin, p=0.744). The rates of adverse events were similar between the two treatments, except for nausea/vomiting (8.9% for tramadol/ acetaminophen versus 1.2% for gabapentin, p=0.030). Caution should be taken in prescribing tramadol at the same time as an SNRI because of the risk of serotonin syndrome, a potentially serious drug interaction.18 Tapentadol Tapentadol is a combined μ-opioid receptor agonist and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. In a pooled analysis of two studies using extended-release (ER) tapentadol (100−250 mg bid)49, pain intensity worsened upon switching from open-label tapentadol ER treatment to placebo during the double-blind maintenance period but was relatively unchanged with continued tapentadol ER treatment. Furthermore, significant between-group differences were observed in other outcomes such as physical functioning, bodily pain and social functioning. Combination therapy Some studies of combination therapy have been conducted in painful DPN, as described above, but overall there is a need for more clinical trials.17,19 Nevertheless, combination therapy, targeting different sites in the pain pathway or neurotransmitter modulation, may be a helpful option in a stepwise treatment approach if initial first-line agents are only partially effective and/or dose escalation is limited because of adverse events.18,19 Combination therapy may result in better tolerability as lower doses of individual drugs may be used when combined with other drugs.19 Other pharmacological treatment options and novel therapies A single application of capsaicin 8% patch was shown in an open-label study to achieve a 31% mean reduction in pain rating among patients with DPN (n=91).50 Overall 47% responded to treatment (≥ 30% pain decrease). The most common adverse events were mild or moderate treatment site burning and pain. Local application of topical agents to the lower limb should only be performed under clinician supervision, as capsaicin and herbal remedies may irritate the skin and lead to infection. Topical capsaicin merits consideration as adjuvant therapy for diabetic neuropathy that is chronically painful and difficult to treat. A 5% lidocaine patch may be considered in the treatment of DPN, as suggested by results of a systematic review of 23 studies.51 The 5% lidocaine patch was associated with pain reduction that was comparable to that achieved with amitriptyline, capsaicin, gabapentin and pregabalin. Intravenous lidocaine infusion may be useful for providing short-term relief in patients with chronic DPN.52 Non-pharmacological management Physical stimulation techniques Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) may be effective in some patients with painful DPN. A meta-analysis of three randomised controlled trials showed that reduction in pain score was significantly greater with TENS than placebo at 4 and 6 weeks, but not at 12 weeks.30 However, subjective improvement in overall neuropathic symptoms was significantly greater at 12 weeks’ follow-up. In contrast, microcurrent TENS did not show any superiority.53 Percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (PENS) has been associated with reduced pain, improved physical activity and quality of sleep, and reduced requirement for non-opioid analgesic medication in diabetic neuropathy.54 Sympathetic blocks may be of benefit to patients with refractory DPN.55 Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) is a more invasive technique, but has been used for the past 30 years for the management of various chronic neuropathic pain conditions.56 Pain management programmes A randomised, controlled pilot study of a cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) approach for painful DPN has demonstrated that patients who received CBT (n=12) had significant decreases in pain severity and pain interference at 4-month follow-up compared with baseline, while those patients who received routine care (n=8) did not achieve any improvements in pain measures.32 No significant changes were observed in depressive symptoms in either group.

Complementary therapy A balanced diet with vitamin supplementation, if necessary, is important for diabetic patients. A randomised, double-blind trial compared three micronutrient treatment regimens over 4 months in 75 diabetic patients: micronutrients (zinc, magnesium, vitamins C and E); micronutrients plus vitamin B (B1, B2, B6, biotin, B12 and folic acid); or placebo.57 Neuropathic symptoms improved in both supplement groups, suggesting that micronutrient supplementation might ameliorate DPN symptoms. Vitamin D deficiency is an independent risk factor for diabetic peripheral neuropathy.58 A case control study of diabetes patients with diabetic neuropathy (n=33) versus those without (n=29) found that serum vitamin D levels were inversely correlated with intensity and presence of nerve conduction velocity impairment.59 In a recent prospective, placebo-controlled trial in 112 patients with DPN and vitamin D deficiency, vitamin D supplementation for 8 weeks improved vitamin D status and was associated with a reduction in neuropathy symptoms versus placebo (p<0.001).60 Acupuncture may also provide pain relief in some patients with DPN. A study comparing 42 patients treated with acupuncture (one session per day for 15 days) with 21 cases exposed to sham acupuncture found that there were improvements in some motor nerve measures and sensory function with acupuncture.31 Acupuncture was more effective than sham for treating numbness and spontaneous pain of the lower extremities and rigidity in the upper extremities than sham. However, use of acupuncture, particularly on the lower limb, may lead to skin aggravation and infection and should be performed with caution. Systematic reviews on the efficacy of Chinese herbal medicine for the treatment of DPN have not found any conclusive evidence to support the effectiveness and safety of topical61 and Chinese herbal medicines.62 Conclusion The prevalence of painful DPN in the diabetic population is high, and efforts should be made to diagnose patients with neuropathic pain symptoms early. While a cure for DPN may not be available, this painful condition can be managed with good glycaemic control and pain management techniques. Based on published clinical evidence and international guidelines, first-line agents for DPN include α2δ-ligands, TCAs and SNRIs. There is no particular preference among the first-line agents, the choice of which depends on physician’ experience and patient' tolerance as well as financial considerations. If a reasonable trial of a first-line agent does not relieve pain effectively, consider combination therapy with or switching to another first-line agent. Tramadol can be considered as a second-line treatment option. Patients with insufficient pain relief after a trial of first-line agents should be referred to a multidisciplinary pain clinic for further treatment options. Acknowledgements Editorial support was provided by Sarah Whorlow, PhD, at MIMS (Hong Kong) Limited, and was funded by the Multidisciplinary Panel on Neuropathic Pain (MPNP) Limited. The MPNP Limited is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Pfizer Corporation Hong Kong Limited.

WY Ip, FRCS, MS, FHKAM (Orthopaedics), European Diploma of Hand Surgery

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, The University of Hong Kong *PP Chen, FFPMANZCA, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology) Department of Anaesthesiology and Operating Services, Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital and North District Hospital, Hong Kong Joseph MK Lam, MBChB, FRCS (Ed), FHKAM (Surgery) Honorary Clinical Associate Professor, The Chinese University of Hong Kong Gavin KW Lee, MBBS, FRCP (Edinburgh), FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine) Director, Rheumatology Centre, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong WK Lee, MBChB (HK), FRCPsych (UK), FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry) Specialist in Psychiatry, Clinical Associate Professor (Honorary), Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong Carina CF Li, MBBS, FANZCA, FHKCA, Dip Pain Mgt (HKCA) Specialist in Anaesthesiology, Hong Kong HW Leung, MBBS, MRCP, FHKAM, MD (Medicine) Specialist in Neurology, Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Medicine & Therapeutics, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong *Vincent Mok, MD (CUHK), FRCP (Edinburgh), FHKAM (Medicine), MRCP Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong TH Tsoi, FRCP, FHKAM (Medicine) Neurology Centre, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong CP Wong, FRCP, FHKAM (Medicine) Specialist in Geriatric Medicine, Hong Kong Steven Wong, Dip Pain Mgt (HKCA), FHKAM (Anaesthesiology) Department of Anaesthesiology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong *Former Multidisciplinary Panel on Neuropathic Pain members Correspondence to: Dr WY Ip, Associate Professor and Chief, Division of Hand and Foot Surgery, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Queen Mary Hospital, 102 Pokfulam Road, Pokfulam, Hong Kong SAR, China. E-mail: wyip@hkucc.hku

References

|

|