|

March 2016, Volume 38, No. 1

|

Discussion Paper

|

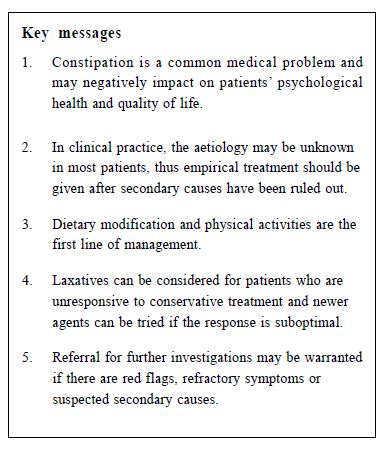

A review on the management of constipation in adult in primary care settingTak-lung Wong 黃德龍,Kwai-wing Wong 黃桂榮,David VK Chao 周偉強 HK Pract 2016;38:28-35 Summary Constipation is a common complaint in general practice. Although the majority is due to functional constipation, it is important to identify and treat constipation appropriately as it may cause mood problems and impose significant economic burden to the society. The mainstay of treatment is lifestyle modification. Pharmacological treatment can be considered if conservative treatment fails. Patients should be referred to specialists for further assessment if simple treatment fails or if red flag symptoms are present. 摘要 便秘是基層醫療醫生經常遇見的問題,雖然多數患者都是功能性便秘,但是由於便秘不僅可能導致患者情緒困擾,同時帶來沉重的社會經濟負擔,因此適當診斷和治療便秘非常重要。主要的治療方法是改變患者的生活方式,若效果欠佳可考慮用藥物治療。當治療無效或出現一些危險的徵狀時,病人就應轉介給專科醫生作進一步的檢查。 lntroduction Constipation is a common clinical problem encountered in general practice, accounting for around 2.5 million doctor visits in the United States1 and around 0.5 million general practitioner visits in the United Kingdom annually.2 The prevalence of constipation varies between regions, ranging from 32.6% in Beijing, 14.0% in Hong Kong, and 8.2% to 52.0% in the United Kingdom.3-5 Women are affected by constipation more often than men.3 Constipation is also commonly seen in patients older than 65.6 As the aging population is increasing, an increase in the prevalence of constipation in the future is expected. In the United States, the direct medical costs for constipation accounted for 230 million per year.7 Constipation is also associated with loss in work productivity. It is estimated that constipation accounted for 13.7 million days of work absence in the United States each year.8 Moreover, higher anxiety and depression scores are noted in patients with constipation and this adversely affect patients’ social life.5 Therefore, it is important for family physicians to identify the problem and manage constipation appropriately. Definition The meaning of constipation can be interpreted differently by patients and physicians. The definitions can range from self-perceived constipation to explicit criteria for research purposes. There is a widespread belief that daily bowel opening is essential for general well-being.9 However, a population based interview in East Bristol showed that only 33% of female and 40% of male reported daily bowel opening.10 In general, constipation means reduced frequency of stool passage from what is regarded as normal pattern by the patient. The American College of Gastroenterology Chronic Constipation Task Force defines constipation as unsatisfactory defaecation with infrequent stool, difficult stool passage, or both, for at least 3 months.11 A consensus group of gastroenterologists in Canada defines constipation as combination of symptoms with fewer than three stools per week, hard or lumpy stool and difficult stool passage for at least six months.12 Rome III criteria13 is frequently used for research purposes, with constipation diagnosed when two or more symptoms out of six are present for at least 3 months:

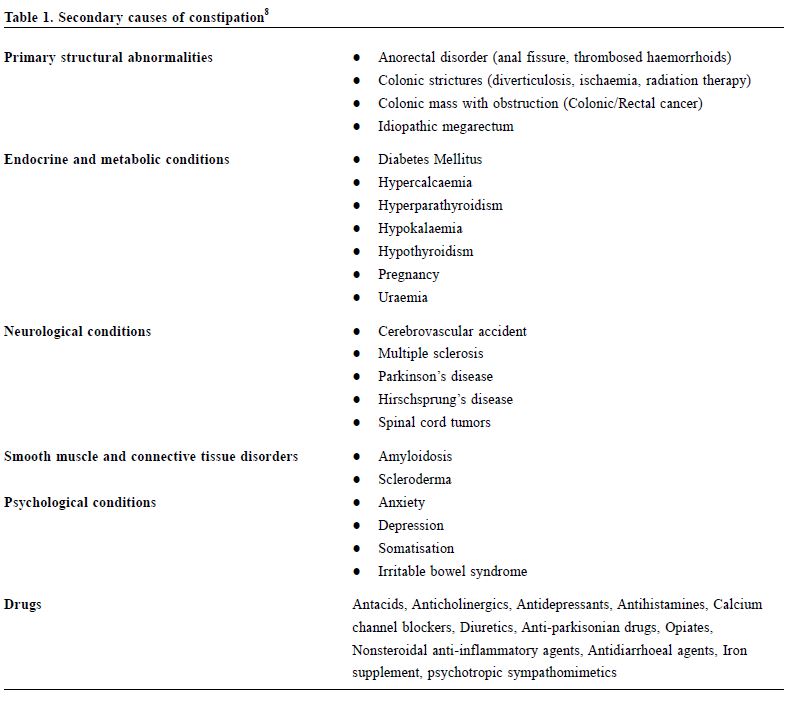

Causes Causes of constipation can be classified into primary (normal transit constipation, slow transit constipation and pelvic floor dysfunction )and secondary causes (Table 1). Normal transit or functional constipation, where no definite cause is found, is the commonest type in clinical practice14 and accounts for 60% of patients with primary constipation.15 Slow-transit constipation and pelvic floor dysfunction accounted for the rest. Slow-transit constipation represents a delay or disturbance in the sequence of colonic peristalsis as a result of an imbalance between inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmitters in enteric nervous system. In pelvic floor dysfunction, failure of evacuation is caused by inappropriate contraction of pelvic muscles or anatomical mal-alignment during defaecation. Identification of secondary causes is crucial as some of them are life-threatening or disabling but are amendable to treatments.

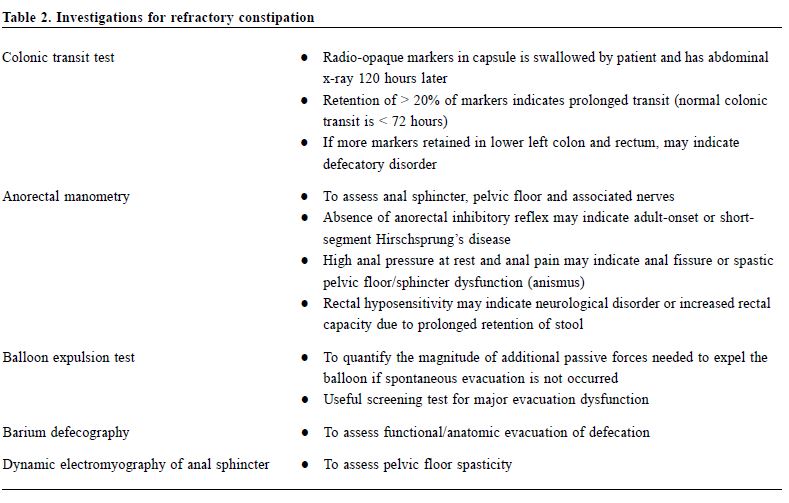

Assessment Most primary care patients with constipation do not require investigations. A comprehensive history and physical examination are adequate for the initial assessment. Further workups should be considered for those who are not responsive to therapies or who present with red flag symptoms. History Patients may have their own perceptions of constipation. It is important to clarify the meaning of constipation with them. The validated Chinese constipation questionnaire was developed for diagnosing functional constipation.16 It consists of 6 items: (1) severity of false alarm, and each severity is graded by a five-point Likert scale from asymptomatic to very severe symptoms. A cut-off point of 5 is used to diagnose functional constipation, with sensitivity and specificity both at 91%. The onset and duration of constipation are important as an acute onset of symptoms is usually associated with secondary causes. Prolonged straining, unusual posture during defaecation and special manoeuvers, such as pressure on the perineum or in the vagina and digital anal evacuation, are suggestive of pelvic floor dysfunction. Assessment of lifestyle risk factors including low fiber diets and lack of physical activity and drug history is crucial. A family history of colorectal cancer should not be missed. Symptoms of endocrine and neurological diseases should be assessed if suspected. Red flag symptoms, such as per-rectal bleeding, weight loss, change in bowel habit and refractory to conservative treatment warrant early investigations. Relevant psychosocial history should also be explored because certain psychological diseases may cause constipation, while constipation itself may lead to psychological stress. Physical examination This is essential to identify the secondary causes of constipation. General assessment of nutrition status, body weight and pallor should be documented. Abdominal tenderness, any mass and organomegaly should be sought. Rectal examination for perianal lesion, sphincter tone and rectal mass may provide clues to the diagnosis. In addition, thyroid and neurological examination may be considered according to the clinical information obtained in the history. Laboratory investigations Routine investigations including blood tests, x-rays or endoscopy are not necessarily recommended for those patients without red flag symptoms.17 Further investigations should be considered when secondary causes are suspected or when the constipation is not responsive to conservative treatment. The initial laboratory tests may include complete blood picture, serum electrolytes, fasting glucose and thyroid function test to rule out the possibility of endocrine or metabolic causes. Other diagnostic tests can be considered for patients with associated alarming clinical features such as age over 50, per rectal bleeding, significant weight loss, family history of inflammatory bowel disease or colonic cancer, acute onset of constipation in old patients, anaemia or positive faecal occult blood test.18 For patients with refractory constipation and symptoms suggestive of slow transit and pelvic floor problem, referral to a gastroenterologist for specialised radiologic and physiologic studies (Table 2) would be warranted. Treatment Lifestyle modification Treatment of constipation should be guided by the causes identified . Fiber is effective in treating constipation and is considered as the initial management.19 Increasing fiber and water intake will increase stool frequency and decrease laxative use.20 Bran is an insoluble fiber; and an intake of 20g per day can increase frequency of bowel motion, faecal weight and decrease bowel transit time.21 Ten to 20 minutes after breakfast, patients are advised to defaecate because spontaneous colonic motility is greatest during this period. The effect of exercise on constipation is still controversial. Moderate physical activities may result in a lower prevalence of constipation.22 A lifestyle modification programme with increasing exercise, fluid and fiber intake is associated with reduction in use of laxative and improvement in quality of life.23 However, another study revealed that increasing physical activity may not improve the symptoms of constipation but it may improve overall well-being instead.24 In general, exercise should be recommended as it improves quality of life and has various health benefits.

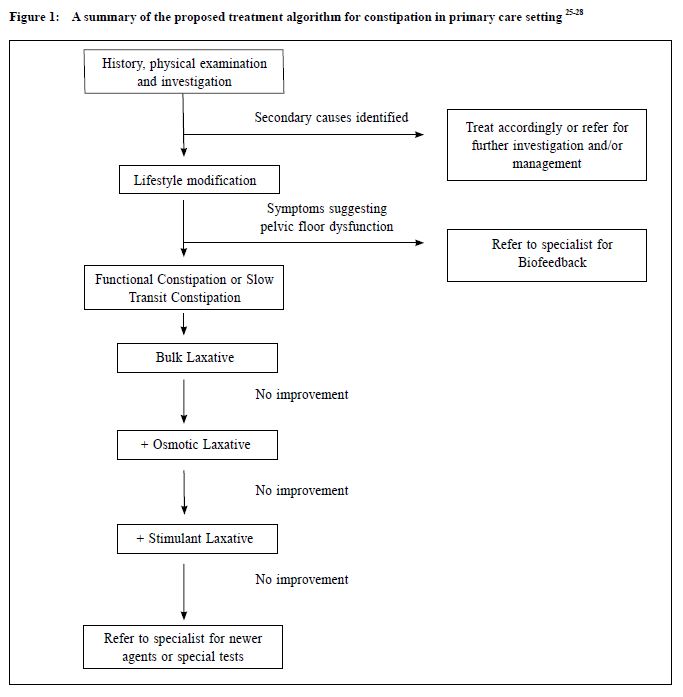

Pharmacological treatment for functional constipation can be given if lifestyle modification fails. The aim is to help patients to achieve regular bowel habit. World Gastroenterology Organisation25 and American Gastroenterological Association26 recommend the use of supplementary fiber or bulk laxative as the first line of pharmacological treatment. Adding osmotic laxative can be considered if the response to the initial therapy is suboptimal and stimulant laxative can be used as the next step. Newer medications, for example 5-HT4 receptor agonist, may be used by gastroenterologists to treat constipation if the patient does not respond to laxatives. A Canadian consensus group27 advises a gradual increase in dietary fiber or fiber supplement as the initial step followed by osmotic laxative. Stimulant laxative is regarded as rescue medication. The Italian Association of Hospital Gastroenterologists and Italian Society of Colo-Rectal Surgery28 share similar recommendations on the treatment algorithm of functional constipation as the above organisations. In patients with symptoms suggestive of pelvic floor dysfunction, biofeedback is the first choice of treatment. For those having functional constipation with poor treatment response, colonic transit test can be arranged and surgical treatment can be considered if refractory slow transit constipation is confirmed. The treatment algorithm is summarised in Figure 1. Conventional laxatives Conventional laxatives including bulk laxatives, osmotic laxatives and stimulant laxatives are effective in improving stool consistency and facilitating colon motility. Bulk laxatives Fiber is the first line treatment for constipation. Bulk laxatives, also known as fiber supplements, should be considered if dietary modification fails, as they have been shown in trials to be more effective than placebo in reducing symptoms of constipation and increasing the mean number of stools per week.29 However, for patients with slow-transit time or pelvic floor dysfunction, constipation may not be improved with dietary fiber. The common side effects of bulk laxatives are abdominal distention, excessive gas production and abdominal cramping. Osmotic laxatives Osmotic laxatives are substances which are not absorbed or poorly absorbed by the gut in order to create an osmotic gradient and draw water into the intestinal lumen. Polyethylene glycol (PEG), lactulose and magnesium salts are commonly used in our locality. PEG is safe for patients with renal or cardiac dysfunction as it does not affect electrolytes. It is also associated with additional bowel motions per week in a meta-analysis.30 Lactulose is a sugar-based laxative; it not only provides osmotic effect by sugar molecules itself but also acts as a substrate for colonic bacteria which produce acid metabolites for additional osmotic effect in the colon. Several old placebo-controlled trials showed that lactulose increases stool frequency.31-33 PEG is more effective with fewer side effects than lactulose.34 However, osmotic laxatives can lead to bloating, diarrhoea, electrolyte disturbances, volume overload or dehydration.

Stimulant laxatives When bulk laxatives and osmotic laxatives are ineffective, stimulant laxatives can be considered. Anthraquinones, e.g. Senna, and diphenylmethanes, e.g. Bisacodyl are the commonly used stimulant laxatives. They not only increase bowel motility by stimulating the colonic mucosa nerve endings but also prevent water absorption in gut by interfering with water and electrolyte transport on the intestinal mucosa. The onsets of action for Senna and oral Bisacodyl are around 6 to 8 hours and 6 to 12 hours respectively. Suppository Bisacodyl will be effective within 60 minutes for quicker relief. Oral Bisacodyl was shown to increased stool frequency, improved stool consistency and decreased symptoms of constipation in a clinical trial.35 However, there are potential risks of habit forming and abuse and it may cause electrolyte disturbance if used inappropriately. Possibility of intestinal mucosa nerve ending damage by stimulant laxatives had been a concern but evidence is lacking. New pharmacological treatment modalities Advanced pharmacological treatments for constipation had been investigated, including serotonin 5-HT4 receptor agonist and colonic secretagogue. Serotonin 5-HT4 receptor agonists Serotonin stimulates the 5-HT4 receptors in enteric neurons to regulate bowel motility. Tegaserod was previously used for chronic constipation by increasing bowel movement, but it was suspended in the United States market since March 2007 because of the increased risks of myocardial infarction, unstable angina and stroke. Prucalopride has a higher affinity to 5-HT4 receptors than to 5-HT1 receptors on blood vessels. It has been shown to increase the number of complete spontaneous bowel movement, improve health related quality of life as well as patient satisfaction.36-37 Prucalopride has been approved in Europe in 2009 as a symptomatic treatment of chronic constipation in women whom laxatives are failed to provide adequate relief. Colonic secretagogues Lubiprostone selectively activates intestinal chloride channels which increase fluid secretion and in turn accelerates small intestinal and colonic transit.38 A double-blind randomised controlled trial has demonstrated its superiority over placebo in increasing spontaneous bowel movements among patients with chronic constipation.39 Although it has been approved by the FDA in 2006, it is not yet available in Hong Kong. Another secretagogue, Linaclotide (registered in Hong Kong in November 2015), is a Guanylin receptor agonist which also induces fluid secretion in bowel lumen and has been shown to significantly reduce bowel symptoms in patients with chronic constipation.40 Other pharmacologicals Probiotic that contains strains of Bifodobacterium, Lactobacillus and E Coli improves frequency of bowel opening and stool consistency in a systemic review of 5 randomised controlled trials.41 Hemp seed pill is a Chinese herbal medication that increases bowel movements in patients with functional constipation.42 Biofeedback is effective in managing pelvic floor dysfunction. A randomised trial showed that biofeedback improved symptoms of pelvic wall dysfunction significantly and was superior to PEG.43 By reflecting the function of anal sphincter and pelvic floor muscle through visual or auditory clues to patients, it facilitates them to learn to control and coordinate the pelvic floor and abdominal muscles. Rererrals Referral to specialist for further investigation is advised if there are red flag symptoms or standard treatments are unresponsive. Although there is no common consensus to define response to treatment, the lack of improvement despite full doses and good drug compliance after 4 weeks warrant further investigations. Conclusions Constipation is a common medical problem and may negatively impact on patients’ psychological health and quality of life. In clinical practice in most patients, the aetiology may be unknown. Empirical treatment is advised after secondary causes have been ruled out. Dietary modification and physical activities is the first line of treatment for functional constipation. Laxatives can be considered for patients who are unresponsive to conservative treatments. Referral for further investigations may be warranted if the patients are refractory to treatments or secondary causes are suspected.

Tak-lung Wong, MBChB(CUHK), FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM(Family Medicine)

Resident Specialist Kwai-wing Wong, MBBS(HK), MPH(HK), FHKAM(Family Medicine) Associate Consultant David VK Chao, MBChB (Liverpool), MFM(Monash), FRCGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine) Chief of Service and Consultant Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care, United Christian Hospital and Tseung Kwan O Hospital, Kowloon East Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR, China. Correspondence to: Dr Tak-lung Wong, Resident Specialist, Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care, United Christian Hospital, 130 Hip Wo Street, Kwun Tong, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China.

References

|

|