|

September 2015, Volume 37, No. 3

|

Update Article

|

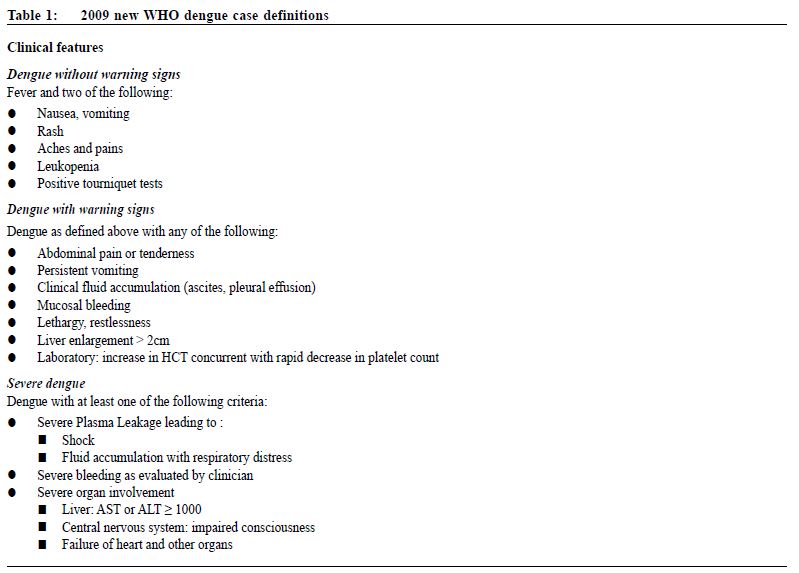

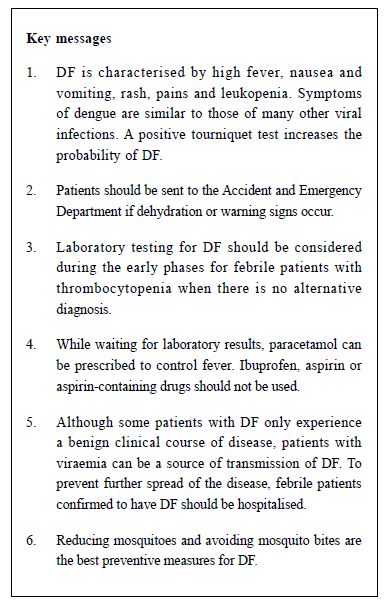

Dengue fever revisitedPui-yi Siu 蕭珮儀,David VK Chao 周偉強 HK Pract 2015;37:101-105 lntroduction Dengue is a mosquito-borne viral infection found in tropical and subtropical regions. Over the recent years, transmission has increased predominantly in urban and semi-urban areas. Three local cases of dengue fever (DF) in October and November 2014 have redrawn public attention to this communicable disease. Transmission Dengue virus is a small single-stranded RNA Flavivirus with four distinct serotypes.1 The various serotypes of the dengue virus are transmitted to humans through bites of infected female Aedes mosquitoes. The Aedes aeqypti mosquito, which is widely distributed around the world particularly in the tropical and subtropical regions, is the primary vector. Its peak biting periods are early mornings and before dusk. Aedes aeqypti is not found in Hong Kong, but the secondary dengue vector Aedes albopictus can also spread the disease. Incubation period varies from 3 to 14 days, commonly 4 to 7 days.2 Epidemiology Dengue is the most rapidly spreading mosquito-borne viral disease globally. In the last 50 years, the incidence has increased 30-fold, with more new countries being affected. Up to 50-100 million infections are now estimated to occur annually in over 100 endemic countries, posing a threat to nearly half of the world’s population.3 In Hong Kong, the number of DF has also increased over the past decade, with 31 to 83 cases reported per year from 2005 to 2010. Although the number dropped to 30 in 2011, the number rose to a new high of 111 in 2014.4 Most cases were imported, but local cases had occurred in 2002, 2003, 2010 and 2014.Clinical features Infection with any one of the four dengue serotypes can lead to a wide spectrum of clinical presentations, ranging from a mild non-specific febrile illness to a severe syndrome of haemorrhage or shock. DF is clinically characterised by a sudden onset of high fever, severe headache, retro-ocular pain, myalgia, arthralgia, anorexia, nausea and rash. However, up to 50% may have no symptoms or signs. Some patients experience a benign clinical course of fever with mild non-specific symptoms, and recover fully without need for in-patient care. These patients are usually young children or those who acquired dengue for the first time. Unless dengue diagnostic serology or molecular testing is performed for these cases, the diagnosis would have remained undetected. Once recovered, immunity to that particular serotype of dengue virus will develop. However, subsequent infections with another serotype of dengue virus may lead to haemorrhage or shock.1,2,6 Some patients may develop severe dengue, which was previously known as Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever and Dengue Shock Syndrome. Severe dengue typically manifests after a two to seven-day febrile phase and is often heralded by clinical and laboratory warning signs. It progresses through three predictable pathophysiological phases:1,6 1. Febrile phasePatient presents with viraemia-driven high fevers which can be up to 40-41oC. Mild haemorrhagic manifestations like petechiae and mucosal bleeding may be seen. 2. Critical/plasma leak phase There would be sudden onset of varying degrees of plasma leak and haemorrhage into pleural and abdominal cavities, following the time when fever abates. Around the time of defervescence, it is important to look for evidence of plasma leak such as tachycardia, pleural effusion and ascites, since intravascular volume depletion and cardiovascular compromise may ensue if it is untreated. 3. Convalescence/reabsorption phase In this phase, plasma leak during critical phase is reabsorbed and patient’s wellbeing appears to improve and patient starts to recover. A new WHO (World Health Organisation) classification was developed in 2009, which categorises the condition into “Dengue without Warning Signs”, “Dengue with Warning Signs”, and “Severe Dengue” (Table 1).7

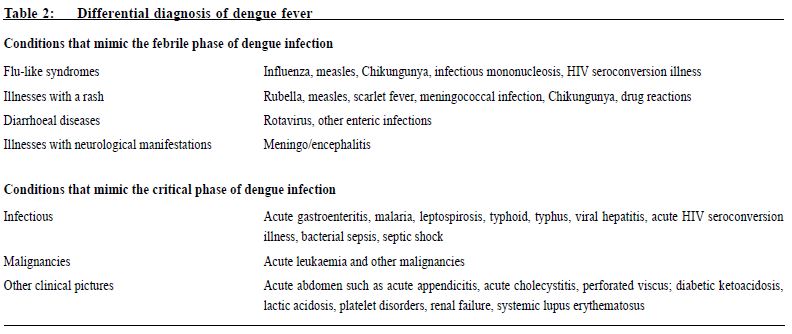

Differential diagnosis Table 2 summarises the differential diagnoses of patients presenting with suspected DF. As can be seen, because of similarity to other viral infections1, diagnosis by clinical presentations alone may be difficult in the early febrile phase. A positive tourniquet test in this phase increases the probability of dengue.1 Investigations Leukopenia is one clinical feature of dengue. Other features are an increased haematocrit with rapid decline in platelet count which are warning signs of shock and necessitate urgent hospitalisation.7,10 Other basic laboratory tests such as liver function test can help to differentiate other diagnosis like hepatitis. However, severe dengue may also present with elevated liver enzymes.7 Laboratory testing for DF should be considered in the early phase for febrile patients with thrombocytopenia when there is no alternative diagnosis.11 Diagnosis requires an acute phase serum sample (within 5 days of symptoms onset). If this sample is negative, a second convalescent serum sample (obtained from day 6 after the onset of symptoms) is necessary to confirm the case. Acute-phase samples will be tested by RT-PCR for virus detection and convalescent-phase samples will be tested for anti-dengue IgM antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA).8

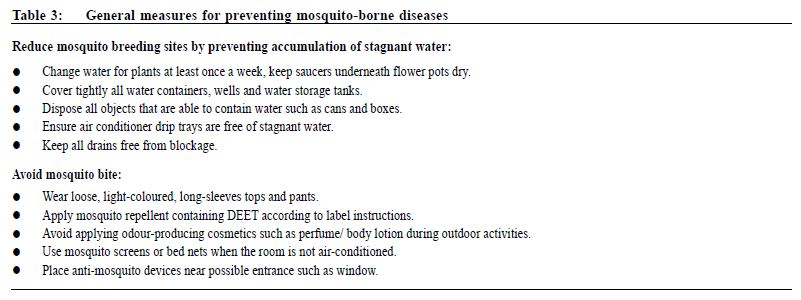

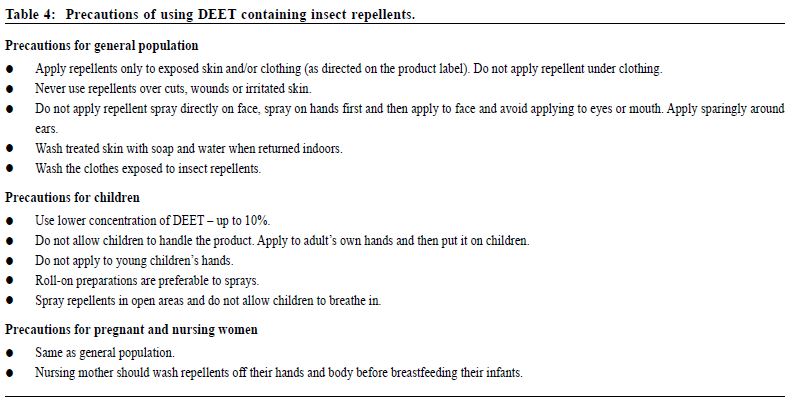

Management It is difficult to predict clinically whether a patient with DF will progress to severe form in initial febrile phase. Continuous assessments are necessary for early recognition of severe manifestations. Presumptive diagnosis of dengue without warning signs should be made for febrile patients who have travelled to endemic areas with two or more features as listed in Table 1. In a primary care setting, suspected cases should have dengue serology arranged and be reported to the Centre of Health Protection’s Central Notification Office. Patients fulfilling clinical and epidemiological criteria of DF should be admitted5, since viraemic patients can be a source of DF transmission9 and spread of the disease. Febrile persons with non-specific symptoms but without a clear travel history or epidemiological link, should be monitored for warning signs as listed in Table 1. Patients should be sent to the Accident and Emergency Department (A&E) if dehydration or warning signs are present. Otherwise, investigations as stated above can be arranged for diagnostic purposes. While waiting for laboratory results, paracetamol can be prescribed to control fever. Ibuprofen, aspirin or aspirin-containing drugs should not be used. Patients and their family should be advised to prevent dehydration by encouraging adequate fluid intake. They should also be advised to seek medical attention if warning signs appear.1,10 There is no pharmacological therapy specific for dengue. DF is mostly self-limiting and treatment is given for symptomatic relief. Patients with severe dengue should be treated promptly with supportive treatment. Most of the complications that arise during the critical period, such as haemorrhage and metabolic abnormalities, are frequently related to prolonged shock. Therefore, the mainstay of treatment is to maintain circulating fluid volume and support vital systems until plasma leak subsides. Fortunately, the critical phase lasts no more than 24 to 48 hours. With appropriate and timely management, mortality rate is less than 1%.2 Prevention There is currently no effective vaccine for dengue fever. Therefore the best preventive measure is to reduce or eradicate mosquitoes and avoid mosquito bite. Table 3 suggests general measures on preventing mosquito-borne diseases.2 DEET containing insect repellent is protective against mosquito bite. However, these should be avoided in children under 6 months of age. Table 4 provides precautions of using DEET containing insect repellents.12,13 Conclusion Dengue fever activities remain high in Southeast Asia, including the various popular tourist attractions for Hong Kong people. Although most of the dengue cases in Hong Kong were imported, local cases have occurred. Dengue fever may progress to haemorrhagic shock with severe and fatal complications. Family physicians have important roles in early identification of warning signs, as well as patient education to prevent mosquito-borne infections.

Pui-yi Siu, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Resident Specialist Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care, United Christian Hospital, Kowloon East Cluster, Hospital Authority. David VK Chao, MBChB (Liverpool), MFM(Monash), FRCGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine) Chief of Service and Consultant Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care, United Christian Hospital, Kowloon East Cluster, Hospital Authority. Correspondence to :Dr Pui-yi Siu, Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care, United Christian Hospital, 130 Hip Wo Street, Kwun Tong, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email:spy293@ha.org.hk

References

|

|