|

September 2015, Volume 37, No. 3

|

Original Article

|

Attitudes and confidence towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation and use of the automated external defibrillator among family physicians in Hong KongPeter KY Lee 李家潤,Mary BL Kwong 鄺碧綠,David SL Chan 陳仕鑾,David KK Wong 王家祺,Tai-pong Lam 林大邦 HK Pract 2015;37:84-92 Summary

Objective: To investigate the attitudes and confidence

towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and using

the automated external defibrillator (AED) amongst

family physicians in Hong Kong.

Keywords: attitudes, confidence, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, automated external defibrillator, family physician, Hong Kong 摘要

目的: 調查香港家庭醫生對心肺復蘇(CPR)和使用自動體

外除顫儀(AED)的態度與信心。

關鍵字: 態度,信心,心肺復蘇,自動體外除顫儀,家庭 醫生,香港 Introduction In recent years , the local community had heightened awareness of sudden cardiac death, as highlighted in the news about athletes’ sudden deaths during the annual Hong Kong Marathon. The importance of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and automated external defibrillator (AED) is increasingly being recognised both within the healthcare profession and in the community. Sudden Cardiac Death (SCD) is defined as “unexpected natural death from a cardiac cause within a short time period, generally < 1 hour from the onset of symptoms, in a person without any prior condition that would appear fatal”.1 It is most frequently caused by sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF) that can be successfully reversed or aborted through timely intervention (e.g. defibrillation). Time to defibrillation is critical: the earlier defibrillation is performed the better the survival rate.2,3 Among VF patients, every minute that passes from time of collapse to resuscitation and/or defibrillation reduces the chance of resuscitation and survival by 7-10%.4 For cases that have collapsed for more than 4-5 minutes, performing CPR before defibrillation increases survival rates.5,6 Very few victims of SCD have survived if defibrillation was performed 8 minutes or more after arrest.7 Despite advances in medical technology and treatment modalities, the survival rate for resuscitated outside-of-hospital Sudden Cardiac Arrest (SCA) patients is only about 33%.2,3 Only 10% are ultimately discharged alive and well from hospital, and many suffered permanent neurological impairment.2,3,8 The most critical element that influences the outcome of a SCA is the elapsed time prior to effective resuscitative restoration (return of spontaneous circulation). Four main factors that can contribute to reducing the elapsed time9:

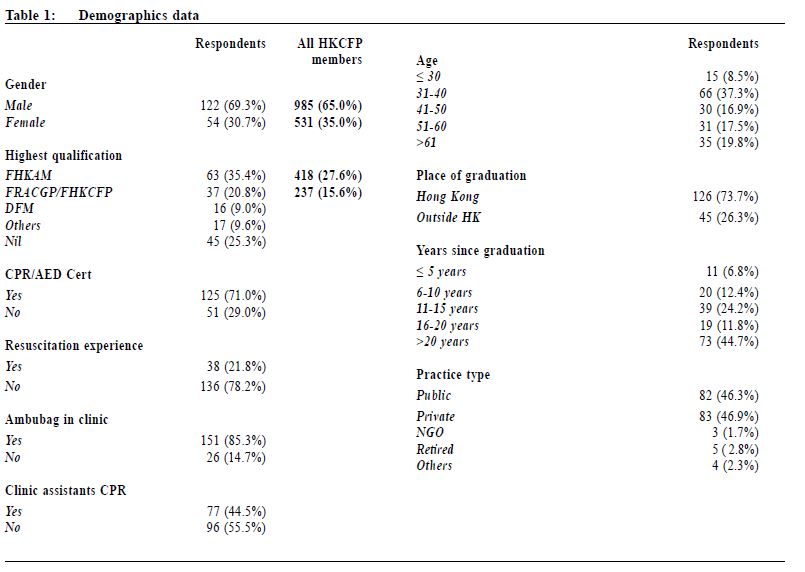

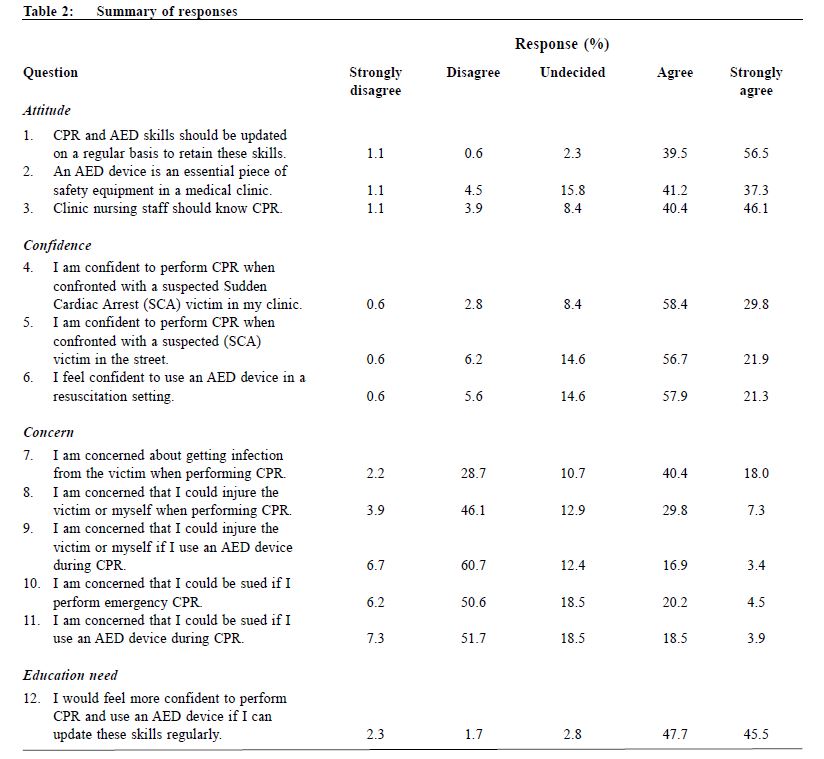

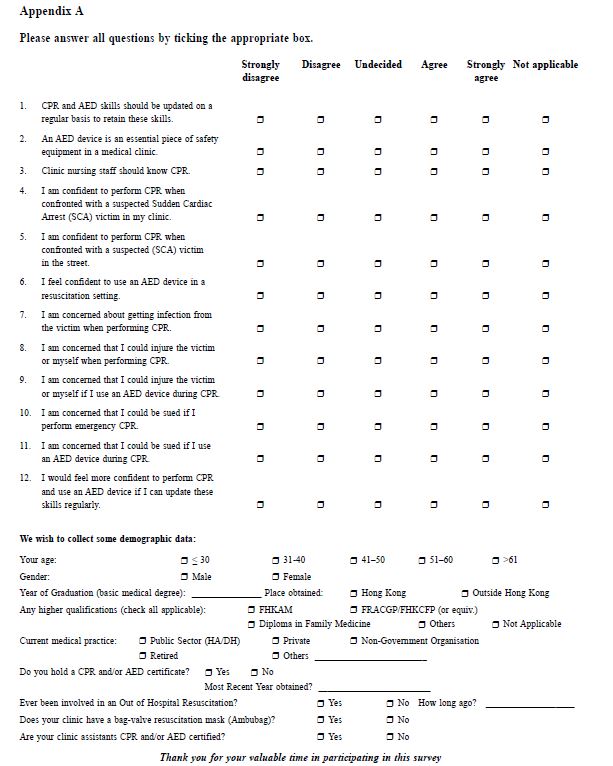

Emergency ambulance services in Hong Kong are provided by the Fire Services Department, with a target response time of 12 minutes; the target was met 93.4% of the time in 2014.10 The recommended response time target of 8 minutes for SCD can be achieved if bystanders, frontline medical personnel like family physicians, nurses and police, who should have CPR and AED skills, are the first responders to situations where a SCD event occur. They can keep the victim’ s circulation going until emergency services personnel arrive with resuscitation equipment. Family physicians in Hong Kong, either working in the public or private sectors, are amongst the frontline staff to respond to victims of accidents, collapsed or unconscious victims, or those with a SCD event. CPR skills, and the knowledge of how to operate an AED if available, are vitally important to provide early and maintain resuscitation long enough until emergency services arrives, potentially improving outcome.9 There is no local data on the incidence of SCD in primary care clinics, but overseas studies found that it is not uncommon for primary care doctors to handle SCD cases. Johnston et al.12 showed that 20% of general practitioners (GPs) surveyed in Queensland, Australia had managed at least one SCD case in the preceding 12 months. In Denmark, 29% of GPs surveyed had a SCD in the clinic.13 In Ireland, Bury et al.14 found 36% of practices surveyed were involved in a SCD during a 5-year period, and 13% had more than one case. This survey was designed to explore Hong Kong family physicians’ attitudes and concerns towards CPR and AED, so that providers of CPR and AED training in Hong Kong can maximise CPR and AED education, confidence amongst doctors and their willingness to act. This will benefit the community by maximising the penetration of CPR and AED skills within the medical community, and ultimately reducing the mortality and morbidity rate for those unfortunate to suffer from SCD. The Hong Kong College of Family Physicians (HKCFP) was chosen to be the target group in this study because its members include family physicians working both in the public as well as the private sectors in Hong Kong. Objective The objective was to find out the attitudes and confidence of performing CPR and AED use amongst family physicians in Hong Kong, and to identify areas that require further attention to help maximise education and training of CPR and AED use. Methods A one page questionnaire survey containing 12 questions and demographic data (Appendix A) was designed. The first 3 questions were on attitudes, another 3 questions on self-perceived confidence, then 5 questions on concerns and lastly 1 question on education needs. Answers were graded on a 5-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. The questions on demographics collected information on age group, gender, year of graduation, post-graduate qualifications, type of practice, CPR certification and whether the clinic worked in had a bag-valve-mask and staff with CPR training. Relevance and content validity of the questionnaire were reviewed by experienced family physicians in the HKCFP Board of Education, and readability and test-retest reliability were pilot-tested on 10 family doctors. Ethical approval was obtained from The University of Hong Kong Human Research Ethics Committee for Non-Clinical Faculties (Ref. number EA251013) prior to commencement of the survey. Data collection 1,516 questionnaires were distributed by post via the monthly mailed newsletter of HKCFP to all College members and fellows. The first round response rate was only 3.0%. Hence a second round targeted distribution of the questionnaire was made to College members during educational meetings held by the College during March and April 2014. All respondents were informed that the survey was voluntary, and if anyone had already filled in the questionnaire before should not submit another questionnaire. The earlier questionnaires returned by members via facsimile or through the post were accepted up to end of June 2014. Data analysis Demographic and cross-sectional data were analysed by simple frequency statistics. Chi-square test was used to compare the responses of respondents grouped into clinic types, possession of CPR certificate, and having postgraduate family medicine qualifications. Results180 questionnaires were collected, amongst which 2 were excluded because of incomplete data. Therefore 178 questionnaires were analysed, giving a response rate of 11.7%. (A) Demographic data The gender distribution of the respondents was comparable to the overall HKCFP member population, while higher proportions of respondents had obtained FHKAM or FRACGP/FHKCFP qualifications. The majority of the respondents graduated in Hong Kong (73.7%). 46.3% and 46.9% worked in the public and private sector respectively. Although 71% were CPR and/or AED certificate holders, only 21.8% had previous resuscitation experience. 44.5% of clinic staff had CPR training. The availability of a bag-valve-mask in the workplace was high (85.3%) (Table 1). (B) Summary of responses Respondents generally had a positive attitude towards CPR/AED (Q1-Q3). 96% respondents agreed or strongly agreed that CPR and AED skills should be updated regularly. 78.5% agreed that AED was an essential clinic equipment, and 86.5% thought that clinic staff should know CPR. The majority of respondents were also confident in performing CPR either within the clinic (88.2%) or in the street (79.2%), and in using an AED in resuscitation (79.2%) (Q4-Q6). 58% of respondents were concerned about risk of infection from victims during CPR, 37.1% feared risk of injury to victim or oneself, and 24.7% feared risk of being sued (Q7-Q11). 93.2% of respondents perceived the need for regular CPR/AED training to update the skills (Q12) (Table 2). (C) Inferential statistics Chi-square test of independence was used to analyse the data by looking at three key factors:

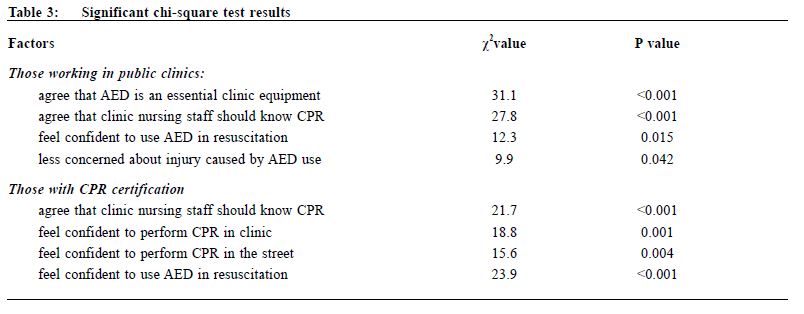

The findings are shown in Table 3. Those working in the public sector were more confident in the use of AED (p=0.015), agreed that an AED is an essential clinic equipment (p<0.001), agreed clinic nursing staff should know CPR (p<0.001), and was less concerned about injury caused by AED use (p=0.042). Those with past CPR training felt more confident in using AED in resuscitation (p<0.001), agreed clinic nursing staff should know CPR (p<0.001), felt more confident to perform CPR in the clinic (p=0.001) or in the street (p=0.004). For factor (iii) , there were no statistically significant differences found between those respondents with postgraduate family medicine qualification and respondents’ attitudes and confidence towards CPR/AED. Discussion While most respondents had positive attitudes and high confidence towards CPR and AED, over half were concerned about infection risk while performing CPR. This concern is understandable after the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in Hong Kong and should be addressed. Recently the effectiveness of “continuous chest compressions only” in CPR is widely studied worldwide in view of increasingly varied infectious epidemics such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome in 2012, and Ebola in 2014. CPR training should include education on protection of rescuer, and make available personal protective equipment (PPE) (either in clinic or in public) at all time. Bhanji et al11 showed that with adequate education about CPR and AED use, the willingness to perform CPR increases, and fear of infection can be overcome. Likewise, concerns about risk of injury or risk of being sued for performing CPR could be reduced through more education and training. Respondents with CPR/AED certification were more confident to perform CPR both in clinic and in the street, were more confident to use an AED in resuscitation setting, and more likely to agree that clinic staff should know CPR. These findings supported the assumption that any person exposed to CPR/AED training and properly trained would feel more confident than those without in dealing with SCD victims. While the majority of respondents had CPR/AED certification, the certificate of only one-third of them were currently valid. Amongst these respondents, 65.2% had higher postgraduate qualifications (DFM/ FRACGP/ FHKCFP/ FHKAM). Holding a valid CPR certificate was a pre-requisite for sitting the HKCFP diploma and fellowship examination. Understandably, after completing the examination, doctors no longer need to recertify themselves, and this is likely to be the reasons for the low rate. The importance of re-certification to maintain and update CPR/AED skills should be emphasised by the training authorities, by employers, and by the College. Compared to family physicians working in the private sector, respondents who work in the public sector showed more confidence in using an AED, less concerned about injuring the victim or themselves when using an AED, and agreed more that clinic staff should have CPR training. This study did not explore the causes of the differences, but a few plausible reasons are suggested based on the authors’ personal experiences:

Conversely, family physicians in the private sector often work in solo or small group practices, and it is plausible that time and financial constraints could mean limited incentives to enrol themselves and their staff for CPR/AED training. Furthermore the availability of AED is likely to be lower among private clinics. The incidence of SCD within a private doctor’s clinic are not uncommon12-14 according the studies in other countries. Often, obtaining and maintaining CPR certification is an individual’s choice. Training authorities should target the private sector to promote CPR/AED training, and both government and non-governmental organisations could provide more training opportunities or funding for training and AED installation, like what has already been done in various public access defibrillation (PAD) programs in Hong Kong.

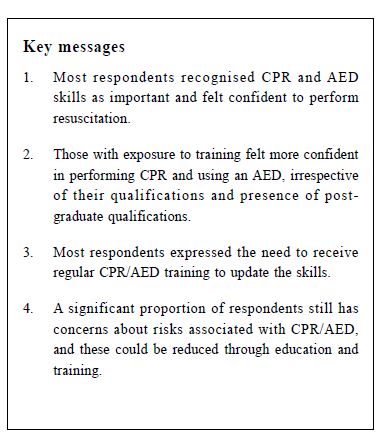

It is common to find many questionnaire surveys suffer from the problem of low response rate. Our study appeared to have an unacceptable first round response rate of 3%. The final 11.7% response rate was also low. This would certainly cause a bias in the data collected. While the second round of data collection at College educational meetings had increased the overall response rate, it also made the self-selection bias to increase, because the attendees were likely to be more motivated to maintain up-to-date medical knowledge and skills. The low response rate could also reflect the lack of importance attached to CPR and AED skills amongst family physicians as a whole, because of the perceived chance of being involved with a SCD in clinic or in the street is low. But as shown from overseas studies12-14, SCD is not uncommonly managed by doctors in primary care clinics. Further research is indicated from this study to explore the knowledge and attitudes of CPR and AED training amongst all primary care doctors in Hong Kong. A cross-sectional study can also provide the incidence rate of SCD and CPR in primary care clinics. The results from this research should help guide the training providers for CPR and AED use in Hong Kong to modify teaching methods for health professionals, in order to improve uptake amongst the medical profession. Conclusion This study showed that most respondents recognised CPR and AED skills as important and felt confident to perform resuscitation. Those with exposure to training felt more confident in performing CPR and using an AED, irrespective of their qualifications and possession of post-graduate qualifications. Most respondents expressed the need to receive regular CPR/AED training to update the skills. A significant proportion of respondents still have concerns about risks associated with CPR/AED, including getting infection, injury to victim or oneself during CPR, and having medico-legal consequences. These barriers could possibly be reduced through education and training. Acknowledgement This study was supported by a grant from the HKCFP Research Seed Fund 2014.

Peter KY Lee, MBBS (Monash), DFM (CUHK), DCH (Syd), FHKCFP

Family Physician Mary BL Kwong, MBBS (HK), FRCP (Edin), FHKAM (Paediatrics), FHKAM (Family Medicine) Specialist in Paediatrics David SL Chan, MBBS (QLD), FHKCFP, FHKAM (Family Medicine), MOM (CUHK) Family Physician David KK Wong, MBChB (CUHK), MSc Healthcare Informatics (University of Bath), FHKCFP, FRACGP Family Physician Tai-pong Lam,PhD (Syd), MD (HK), FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine) Professor Department Family Medicine & Primary Care, The University of Hong Kong Correspondence to : Dr Peter KY Lee, KCC FM & GOPC Department Office, Room 807, 8/F, Block S, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, 30 Gascoigne Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: dragonarms@gmail.com.

References

|

|