March 2014, Volume 36, No. 1 |

Update Articles

|

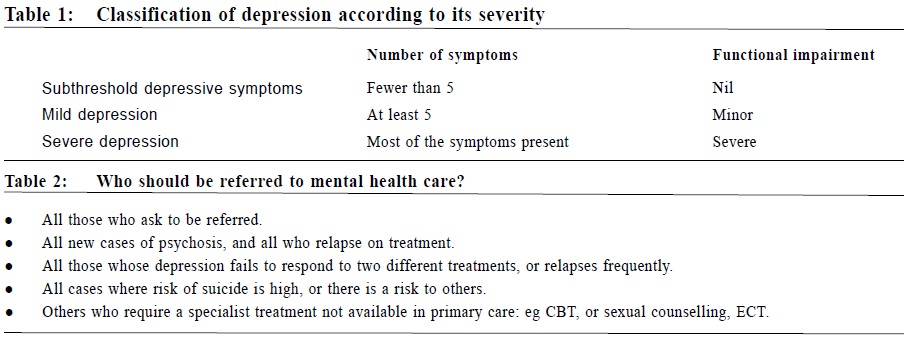

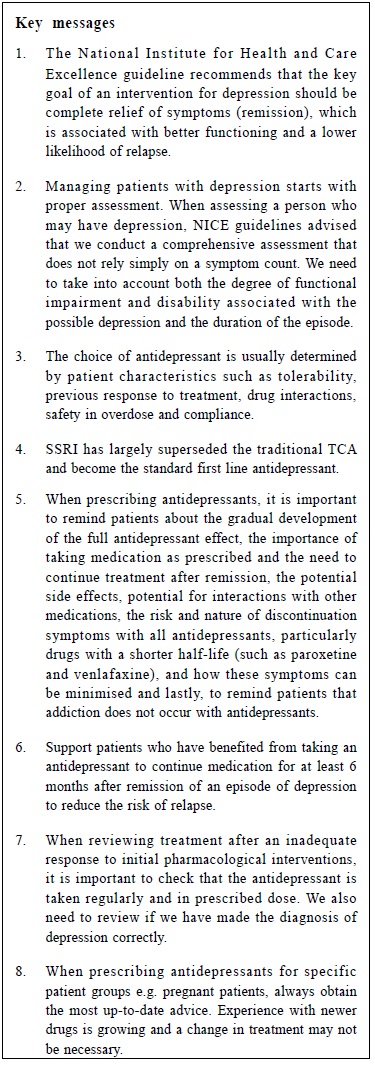

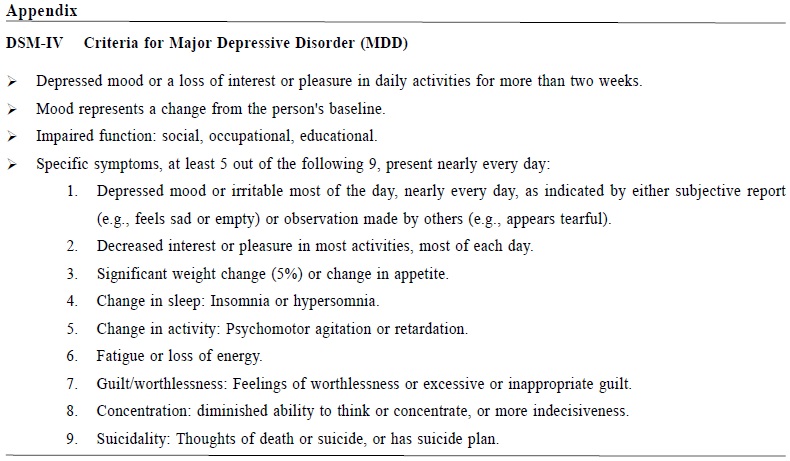

Update on the management of depressive disorder in primary care settingsMimi MC Wong 黃美彰 HK Pract 2014;36:12-19 Summary Depression is a mental illness commonly encountered in primary care settings and the majority of mild depression can be treated by family physicians. Well established guidelines are available to refer to for the proper management of patients with different severity of depressive disorders. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline recommends that the key goal of an intervention should be complete relief of symptoms (remission), which is associated with better functioning and a lower likelihood of relapse. There is no good evidence to show that any one class of antidepressant is clearly superior in terms of efficacy or speed of onset of action. With the availability of many different types of antidepressants in the market, the choice of antidepressant should be determined by patient characteristics such as tolerability, previous response to treatment, drug interactions, safety in overdose and compliance. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have largely superseded tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) to become standard first line therapy. 摘要 抑鬱症是基層醫療的醫生們經常遇見的精神疾病。大部份輕度抑鬱的患者都適合在基層醫療接受治療。現時已有治療不同程度抑鬱症的指引。英國臨床質量標準署有關抑鬱症的指引,建議抑鬱症治療應以完全控制症狀(緩解)為目標,以提升患者的能力及減低復發機會。現有的文獻亦証明特別治療,包括藥物,能有效地控制病情較重及持續較長時間的抑鬱症。至今為止,沒有證據証明任何一種抗抑鬱藥更為優勝。選擇抗抑鬱藥應注重病人的特質,例如對個別藥物的適應情況、過往對藥物的反應、藥物的相互作用、過量服用藥物時的安全性及對服用藥物的遵從程度等等。現在有多種抗抑鬱藥透過不同的機理作用控制抑鬱症症狀,熟悉它們的機理作用有助明白藥物的各種副作用。血清素現在已取代三環抗抑鬱藥成為第一線的抗抑鬱藥。 Introduction Depression is a mental illness commonly encountered in primary care. Therefore, it is important for family physicians to familiarise themselves with the diagnostic criteria and management. Family physicians can refer to existing guidelines that provide information on management of different severities of depression. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines (NICE) NICE was established as a Special Health Authority for England and Wales in 1999. It has systematically developed statements derived from the best available evidence that assist clinicians and patients in making decisions about appropriate treatment for specific conditions. Where evidence is lacking, the guidelines incorporate statements and recommendations based upon the consensus statements developed by the Guideline Development Group (GDG). The latest guideline for Depression in Adults (CG90)1 was published in October 2009 and revised again in October 2012. This latest update used the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th. Edition (DSM–IV) rather than the International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD–10) to define the diagnosis of depression because the evidence-based for treatment nearly always use DSM–IV. Apart from assessing patient symptoms, the initial assessment of a patient presenting with depressive features should also take into account the duration of illness, as well as the degree of functional impairment and associated disabilities. Classification of depression according to its severity Table 1 shows the difference between sub-threshold depressive symptoms, mild depression and severe depression. For moderate depression, the number of symptoms or functional impairment are between ‘mild’ and ‘severe’. For severe depression, it can occur with or without psychotic symptoms. Patients with sub-threshold depressive symptoms most commonly present to primary care.3 Risk assessment Patients with depression must be directly asked about suicidal ideation and intent. If there is a risk, the adequacy of social support and patients’ aware of sources of help should also be assessed. It is important to note that those younger than 30 years of age have an increased prevalence of suicidal thoughts after antidepressant initiation.12 Urgent referral to specialist mental health services or the Emergency Department should be considered if there is immediate risks to the patient himself/herself or others. At times, compulsory admission to a mental hospital against patient’s wish might be necessary for the protection of the patient or others. Table 2 provides further information about conditions which require referral to specialist mental health services.

Treatment for sub-threshold depressive symptoms or mild depression Where possible, the key goal of an intervention should be complete relief of symptoms (remission), which is associated with better functioning and a lower likelihood of relapse.4 Antidepressants may offer little or no advantage over placebo for patients with sub-threshold depressive symptoms or mild depression5,6, because patients often improve spontaneously and respond well to non-specific measures such as support and monitoring. For people with persistent sub-threshold depressive symptoms or mild to moderate depression, other interventions including cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), computerised CBT or structured group physical activity programme may be useful. Treatment for moderate to severe depression Antidepressants should be considered for the following patients:

Choice of antidepressants Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) is now recommended as the first line antidepressant.7 Citalopram or sertraline have less propensity for drug interactions.8 When prescribing antidepressants, be aware that dosulepin should not be prescribed with non-reversible monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs; e,g, phenelzine). Combined antidepressants therapy and lithium augmentation of antidepressants should normally only be prescribed by psychiatrists. Toxicity in overdose must be considered among patients with significant suicidal risks. Venlafaxine is associated with a greater risk of death from overdose comparing with other equally effective antidepressants recommended for routine use in primary care. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), except for lofepramine, are associated with the greatest risk in overdose.9 Drug interactions with SSRIs Although SSRIs are relatively safe antidepressants, it is important to be aware that it inhibits liver enzymes thus affecting the metabolism of other medications. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) SSRIs will increase risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.10 If no suitable alternative antidepressant available for use, SSRIs and NSAIDs should be co-prescribed together with gastroprotective medicines (such as proton-pump inhibitors). Warfarin, heparin and aspirin SSRIs should not be prescribed to patients taking warfarin or heparin because of their anti-platelet effect. Noradrenergic and Specific Serotonergic Antidepressant (NaSSA) could be considered as alternative. When aspirin is used as a single agent, safer alternatives such as trazodone, mianserin or reboxetine should be considered. If no suitable alternative antidepressant is available, SSRIs and aspirin may be co-prescribed with a gastroprotective. Other drugs Among patients taking triptans or MAO-B inhibitors, safer alternative such as mirtazapine, trazodone, mianserin or reboxetine should be considered. Starting treatment When prescribing antidepressants, patients should be reminded of the following:

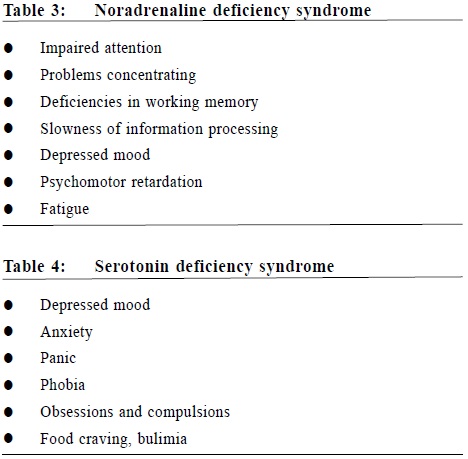

After starting an antidepressant, patients with no suicidal risks should be reviewed after 2 weeks, and then every 2 to 4 weeks for the first 3 months. Follow up intervals can be longer if treatment response is good. Patients having a suicide risk (including those younger than 30 years of age) should normally be seen after 1 week; and then, frequently thereafter as appropriate, until the risk is no longer considered clinically important. Short-term concomitant treatment with a benzodiazepine, prescribed on an as required basis, can be considered if anxiety, agitation and/or insomnia are problematic. In order to prevent the development of dependence, NICE guidelines recommended against the use of benzodiazepines for longer than two weeks. However, in clinical practice, benzodiazepines may need to be prescribed for a longer duration. Doctors must remind patients about the risk of dependence, not to increase the dosage themselves and the importance to take it only when required. Support patients who have benefited from taking an antidepressant to continue medication for at least 6 months after remission of an episode of depression to reduce the risk of relapse. If a patient's depression shows no improvement after 2 to 4 weeks with the first antidepressant, check that the drug has been taken regularly and in the prescribed dose. If response is absent or minimal after 3 to 4 weeks of treatment and with an adequate therapeutic dose, increase the level of support (for example, by having weekly face-to-face or telephone contacts) and consider increasing the dose within the safety limit if there are no significant side effects or switching to another antidepressant if there are side effects or if the patient prefers.13 If the patient's depression shows some improvement by 4 weeks, continue treatment for another 2 to 4 weeks. Consider switching to another antidepressant if response is still not adequate or there are side effects. When there is poor response to treatment If an antidepressant has not been effective or is poorly tolerated, consider offering other treatment options, including high-intensity psychological treatments or prescribe another single antidepressant (which can be from the same class) if the decision is made to offer a further course of antidepressants. When reviewing treatment after an inadequate response to initial pharmacological interventions, it is important to check that the antidepressant is taken regularly and in prescribed dose. We also need to review if we have made the diagnosis of depression correctly. Mood disorder secondary to alcohol, substances, medications and general medical conditions, such as hypothyroidism would result in persistence of depressive symptoms despite adequate antidepressant treatment. Try to increase dose within permitted range in a gradual manner. Switch to another antidepressant if poorly tolerated or if no response in one month.14 It is important to bear in mind that some patients are very sensitive to the side effects of antidepressants or the somatic symptoms experienced as a result of depression would be mistaken by some to be the side effects of antidepressants prescribed to them. For these patients, it is important to start at a low dose, titrate slowly and encourage them to continue the antidepressants for up to a week. As the body needs time to adapt to a new medication, mild uncomfortable feelings associated may gradually disappear after a few days. For those who are reluctant to further increase the dosage of the antidepressants, switching to another antidepressant may be needed. When switching antidepressants, consider initially, a different SSRI or a better tolerated newer-generation antidepressant. At times when a single antidepressant is not enough to control the symptoms, combination of antidepressants may be an option. Do not normally combine antidepressants in primary care settings without consulting a specialist. It is important to select medications that are safe to use together, be aware of the increased side-effect burden and inform them if off-label medication is offered. It is a good practice to have thorough discussion with patients and with proper documentation. Make sure that you are familiar with the primary evidence and consider obtaining a second opinion if the combination is unusual, the evidence for the efficacy of a chosen strategy is limited or the risk–benefit ratio is unclear. Besides augmenting an antidepressant with another antidepressant, lithium or an antipsychotic such as aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine or risperidone can also be used.15 Mechanism of actions of antidepressants In order to understand how antidepressants help to treat depressive symptoms, we need to understand the monoamine hypothesis. Depression is the result of a deficiency of monoamine neurotransmitters which include noradrenaline, serotonin and dopamine. Antidepressants act by increasing the activity of these neurotransmitters in the brain by various mechanisms. Please refer to Tables 3 and 4 for symptoms associated with noradrenaline and serontonin deficiency syndrome.16 Lacking of dopamine affects one’s mood, attention and concentration.

Types of antidepressants There are different types of antidepressants available in the market with different mechanism of actions.17 It is useful to be familiar with their mechanisms which will give a better understanding concerning their side effects profile and help to choose the most appropriate antidepressants for patients. Commonly available antidepressants in Hong Kong include SSRI, TCA, Serotonin-Noradrenaline Reuptake Inhibitor (SNRI), NaSSA, Serotonin Antagonist Reuptake Inhibitor (SARI) and Norepinephrine and Dopamine Reuptake Inhibitors (NDRI). There is no good evidence to show that any one class of antidepressant is clearly superior in terms of efficacy or speed of onset of action. The choice of antidepressant is usually determined by patient characteristics such as tolerability, previous response to treatment, drug interactions, safety in overdose and compliance.18 SSRI has largely superseded the traditional TCA and become the standard first line antidepressant.19, 20 Mechanism of action of different types of antidepressants Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) TCA is a noradrenaline and serotonin reuptake inhibitor. It also blocks alpha-1- receptor which results in postural hypotension, histamine-1-receptor which results in sedation and weight gain and muscarinic-1-receptor which results in anticholinergic side effects including dry mouth, blurring of vision, constipation and urinary retention. It is cardiotoxic and therefore it can be fatal in an overdose. Special attention need to be paid when used in those with cardiac problem. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) SSRI is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.21 Generally it is not sedative and has very little anticholinergic side effects. It is not cardiotoxic which is safer in patients who have risk of deliberate self-harm. It increases the availability of serotonin which will exert its effect on different serotonin receptors. If serotonin exerts its effect on 5HT1A receptors, anxiety and depressive symptoms would be improved. If it exerts its effect on 5HT2A and 5HT2C receptors it causes anxiety, panic symptoms and sexual dysfunction. If it exerts its effect on 5HT3 and 5HT4 receptors, it causes nausea and gastrointestinal (GI) upset. That is why SSRI has increased agitation, sexual dysfunction, nausea and GI upset. It increases a number of liver enzymes (e.g. CYP2D6 and CYP3A4), therefore it may cause drug interactions by increasing the plasma levels of some other medications. Noradrenergic and Specific Serotonergic Antidepressant (NaSSA) Mirtazapine (Remeron) is an example of NaSSA. It increases the release of both noradrenaline and serotonin by inhibiting the presynaptic alpha-2-adrenergic receptor.22 It antagonises the serotonin 2-A, 2-C and 3 receptors so that the serotonin would be diverted to serotonin 1-A receptors. Therefore unlike SSRI, it does not have the side effects of anxiety feelings, increased agitation and GI upset. It also antagonises histamine H-1 receptors, giving rise to its sedative properties. Common side effects include sedation, dizziness and weight-gain. Serotonin-Noradrenaline Reuptake Inhibitor (SNRI) Venlafaxine (Efexor, Efexor XR), Duloxetine, Desvenlafaxine, Milnacipran are examples of SNRI.23 It has the dual action reuptake inhibitory properties of the TCAs but does not have the side effects of TCAs because it has very little activity on cholinergic, histaminergic and alpha-1-adrenergic receptors. At lower dosage, it resembles the properties of a SSRI; while at higher dosages, its dual-action properties become prominent. In a meta-analysis, venlafaxine has been shown to be superior in inducing remission than SSRIs.24 In general, it is well tolerated; but the most troubling side effect is its tendency to induce hypertension in some patients. Serotonin Antagonist Reuptake Inhibitor (SARI) Trazodone belongs to the SARIs. It inhibits reuptake of serotonin and at the same time blocks 5HT2A receptors so that the serotonin concentrates on 5HT1A receptors.25 It also block H-1 which causes sedation and weight-gain. It blocks alpha-1 receptors which may result in priapism (prolong and painful erection). Therefore it is important to remind male patients about this side effect. Norepinephrine and Dopamine Reuptake Inhibitors (NDRI) Bupropion belongs to the NDRIs. It lacks serotonin component which is good for those who are unable to tolerate serotonergic side effects of the SSRIs.26,27 Choice of antidepressants for particular patient group Children and adolescents Fluoxetine is the first line pharmacological treatment for depression in children and adolescents.28 Citalopram and Sertraline are other alternatives recommended by NICE. Elderly SSRIs are generally better tolerated than TCAs.29 However, it may increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding in vulnerable elderly. It is also important to monitor drug interactions if SSRIs are used as most elderly are taking other medications at the same time. Those with less tendency for drug interactions, e.g. citalopram and escitalopram would be the safest in this aspect.30 Pregnant women The relapse rates of depression are high in those patients who discontinue medication during pregnancy. The risks of not treating depression include harm to mother through poor self-care, lacking of obstetric care or self-harm as well as harm to foetus or neonate (ranging from neglect to infanticide). This is most often seen with amitriptyline, imipramine and fluoxetine.29 If the patient is established on another antidepressant, always obtain the most up-to-date advice. Experience with other drugs is growing and a change in treatment may not be necessary. Breastfeeding women If the mother has taken a particular antidepressant during pregnancy and until delivery, continuation with the drug while breastfeeding may be appropriate as this may minimise withdrawal symptoms in the infant. Sertraline, paroxetine, nortriptyline and imipramine are recommended drugs in breastfeeding.29 Patients with liver and renal impairment For those patients with liver impairment, it is important to start with low dose and titrate slowly. Imipramine, paroxetine or citalopram are recommended choices.29 For those with renal impairment, no one agent is clearly preferred to another. However, citalopram and sertraline are suggested as reasonable choices.29

Conclusion Depression can be a serious mental illness with significant functional impairment but the good news is that it is a treatable condition. Patients may not be aware of their mood problems and very often they would not take the initiative to seek treatment. Family physicians play an important role in the recognition of the condition especially when the patients present themselves for the somatic symptoms they have been suffering as a result of their depression. It is important for family physicians to familiarise themselves with different treatment modalities, in particular medication treatment for depression.

Mimi MC Wong, MB BS (HK), MRCPsych, FHKC Psych, FHKAM(Psychiatry), Correspondence to: Dr Mimi MC Wong, Department of Psychiatry, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong SAR. References

|

|