|

December 2013, Volume 35, No. 4

|

Update Articles

|

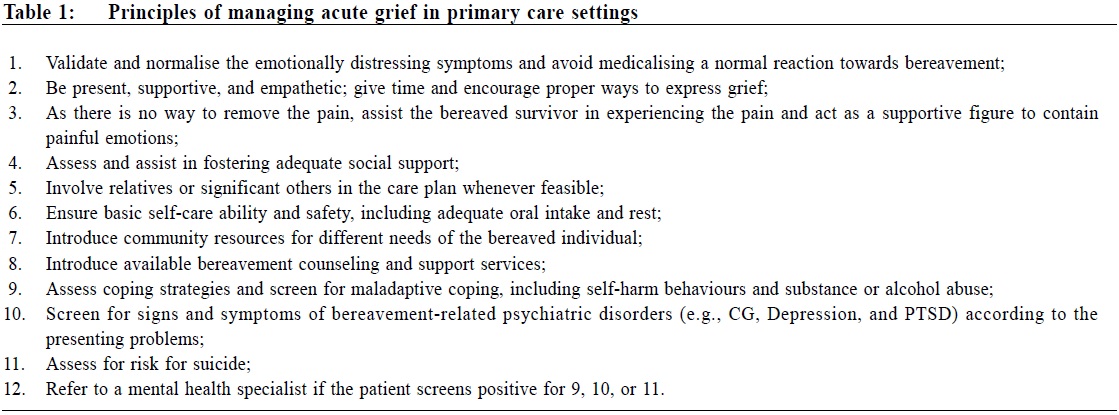

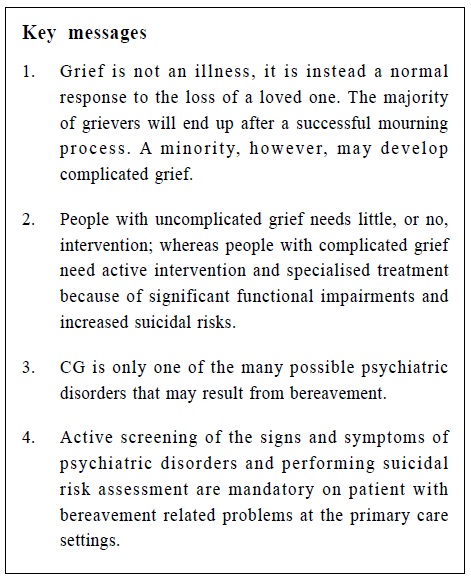

Update on grief and complicated grief; and an introduction to the specialised treatment programme for complicated grief in the Common Mental Disorder Clinic of United Christian HospitalAdrian KH Sham 沈君豪, Peter WC Tam 譚偉聰, Gillian PK Wong 黃碧君, Michael GC Yiu 姚家聰 HK Pract 2013;35:108-117 Summary There is concrete evidence that a small percentage of bereaved grievers would suffer exceptionally profound and prolonged grief symptoms which exceed the usual level experienced by most grievers, associated with significant functional impairments. This condition is termed complicated grief. Complicated grief (CG) is a form of mental disorder which differs slightly from the common psychiatric disorders such as the affective disorders, with its unique clinical symptoms, risk factors, health outcomes, as well as response to treatment. The usual pharmacological and psychological treatments for depressive disorders have only limited effect on patients with CG. Evidence shows that CG patients need specific and targeted treatment, which is currently not readily available in Hong Kong. The Common Mental Disorders Clinic in the Kowloon East Cluster of the Hospital Authority offers a pilot multidisciplinary treatment programme for CG patients, with the hope of arousing an awareness among the public as well as health professionals on this debilitating condition and its management. 摘要 有明確證據顯示少部分人喪親哀傷人仕會感受額外深切而持續的悲痛,超過多數人所經歷的悲傷水準。而且伴有明顯的功能障礙。這種情況稱為複雜性悲傷。複雜性悲傷是一種別於其他精神疾病的精神疾患。它有獨特的臨床症狀、危險因素、治療反應和健康結果。一般的抗抑鬱藥物和心理療法對複雜性悲傷患者成效不彰。證據顯示,複雜性悲傷患者需要特定的針對性治療,而香港目前正缺乏此類治療。九龍東聯網的常見精神病診所為這些複雜性悲傷患者開設了一項試驗性多學科治療計劃,希望能喚起大眾和醫護專業人員對這種折磨人生疾患的關注。 Introduction The loss of a loved one is an almost inevitable and universally experienced life event. It is also one of the most difficult and painful experiences that we will ever have to go through. In most cases, the mourning process eventually leads to a restored psychological equilibrium. However, a minority of grievers will experience persistent and disabling grief responses that are associated with profound functional impairments. This condition is termed Complicated Grief (CG). The highly individualised and heterogeneous nature of grief, the lacking of a consensus for diagnostic criteria for complicated grief, and the emotionally demanding nature of bereavement per se may all pose significant challenges to clinicians when encountering patients with bereavement-related problems in primary care settings. Although organisations offering grief counselling services are readily available in Hong Kong, CG is a highly specific condition that warrants specialised treatment, which is currently not readily available in our locality. This article provides a brief review of the concepts of grief, CG, and the treatment of CG. Management principles for bereaved patients in primary care settings are suggested. Finally, a specialised CG treatment programme available in the Kowloon East Cluster of the Hospital Authority in Hong Kong, will be introduced. Grief Grief is an instinctive psychological and behavioural response secondary to bereavement. Typical thoughts, feelings and behaviours occur, which vary considerably in their pattern, intensity, and duration among individuals and among cultural groups.1,2 Nevertheless, most mourners experience intense emotions in the early aftermath of a death, which are typically characterised by intense sadness, recurrent yearning and preoccupation with thoughts and memories of the deceased, a sense of disconnection from ongoing life, and feelings of incompetence; behaviourally, the mourner tends to alternate between proximity seeking and avoiding reminders of the deceased. Natural capabilities to engage with others and explore the world are restrained. Daily rhythms could become disorganised, and biological functions, such as sleep, appetite and energy, are often disrupted. This process is called acute grief 3; it primarily results from the distress caused by separation from the attachment figure.4 As grief progresses, it oscillates between confronting the loss and setting this painful information aside as learning and emotional regulation operate. Bowlby wrote that in the midst of bouts of grief, our minds naturally move away from acknowledging such painful information, providing us with periods of respite.4 Stroebe et al described the dual process model, in which coping entails adjusting to the loss and restoration.5 Somehow, people find ways to accept and integrate the reality of death and restore their capacity for enthusiasm, joy, and satisfaction; at this point, the grief is said to be "integrated", which is the hallmark of successful mourning. A successful mourning process entails effective emotion regulation and the assimilation of new learning (including the loss of a loved one) into long-term memory. Grief, per se, is neither an illness nor a problem; rather, it can be viewed as an instinctive healing proces s that will progres s naturally if it is not impeded.6 Nevertheless, it can be challenging for family physicians to handle patients presenting with biological or emotional disturbances in the midst of the acute grieving state. Table 1 illustrates the recommended principles for managing patients with acute grief in the primary care setting.

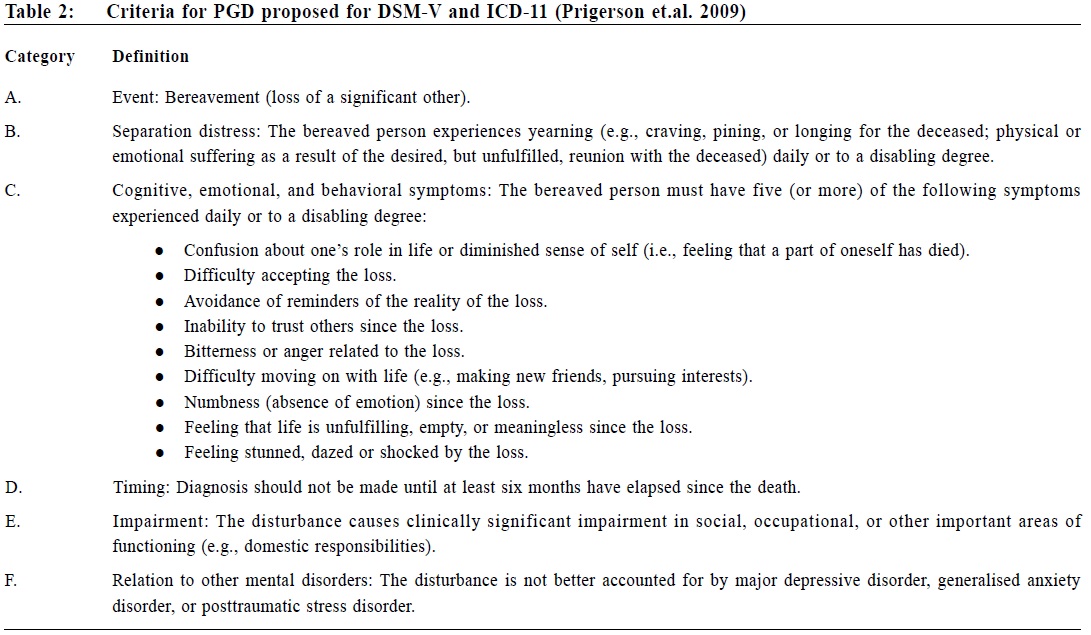

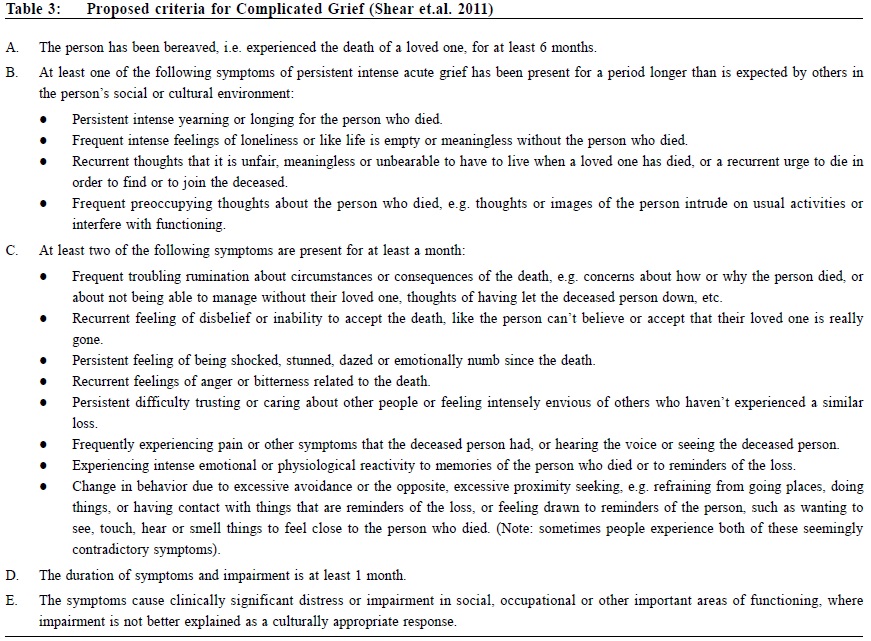

Ineffective emotional regulation, dysfunctional automatic thoughts, maladaptive coping behaviours, use of substances, and social or physical deprivation are behaviours that can complicate the grief process.7 In such circumstances, the person could be stuck at the stage of acute grief for an excessively long period. These patients are at high risk for developing CG. Complicated Grief Characteristics and clinical features Patients with CG suffer intense and prolonged acute grief symptoms, which are associated with an array of complicating thoughts, feelings and behaviours. Many CG symptoms stem from separation distress, which is characterised by a strong psychological protest against the reality of loss and a reluctance to adjust to a life without the loved one, so much so that it becomes pathological. CG is usually characterised by an intense yearning for the person who died, which is associated with persistent, intrusive and preoccupying thoughts of the deceased person. Without the lost loved one, CG patients feel that they have lost their meaning or purpose in life, or they may have difficulty focusing on the present, carrying on into the future, or concentrating on things apart from the loss. A common feeling of being disconnected from people to whom they formerly felt close further exacerbates the sense of helplessness and loneliness. As a result, patients with CG will find it extremely difficult to re-adjust to life, form other interpersonal relationships or engage in potentially rewarding activities 8,9, which in turn perpetuates the CG symptoms and traps the patient in a vicious cycle. Diagnostic issue and criteria Although CG is not currently an officially recognised diagnosis in the DSM-5 or ICD-10, it is being put in the appendix of the newly released DSM-5 as an area for further study. The ICD-11 working group is considering adding "Prolonged Grief Disorder" (another term to describe CG) to the upcoming diagnostic manual in 2015. This consideration is not novel. Horowitz and colleagues 10-12 proposed including CG in the DSM more than two decades ago. The group proposed including CG as a stress-response syndrome in the DSM-IV; however, the evidence in favour of this was eventually determined to be insufficient for its inclusion at the time. Since then, evidence supporting the existence of CG has continued to accumulate.12-17 To date, Prigerson et al18 have proposed a set of diagnostic criteria for Prolonged Grief Disorder (Table 2), while Shear et al19 have also proposed another comprehensive set of criteria for Complicated Grief (Table 3). Given the abundant available evidence, the existence of CG as a psychiatric disorder should be justified; however, consensus for diagnostic criteria are still wanting for this highly complex condition.

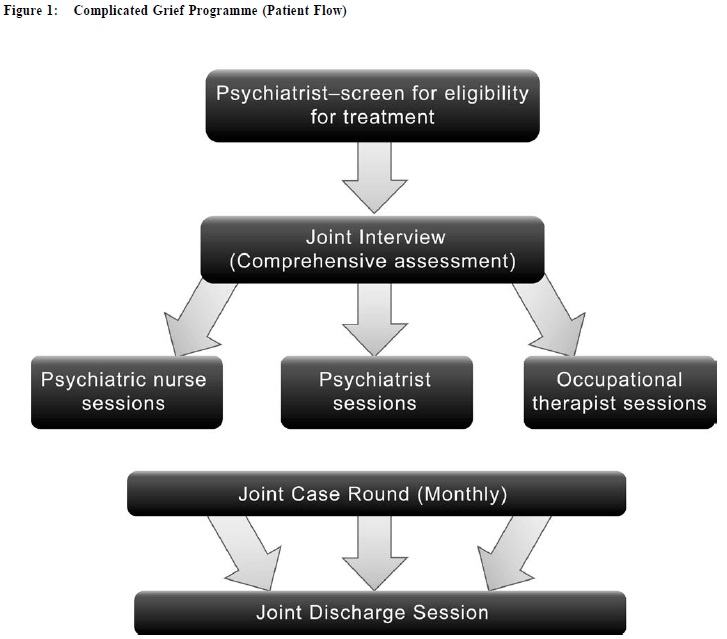

Distinction of CG from other psychiatric disorders secondary to bereavement CG is by no means the only, nor necessarily even the primary, complication that may follow bereavement; rather, it is one of many possible disorders that may result from bereavement. Conditions such as depression, stress-related disorders, particularly including post-traumatic stress disorder 20, anxiety spectrum disorders, substance-related disorders, and even psychotic disorders, can arise. Though it is often difficult to conceptualise the difference between CG and other bereavement-related psychiatric disorders, it is not difficult to envision the analogy that after a severe physical trauma, the victim could develop post-traumatic stress disorder, panic disorder, depression, or any combination of the above. CG and other mood disorders are distinct but not exclusive conditions. Various studies have shown that CG symptoms form a coherent cluster that differs from bereavement-related depressive or anxiety symptoms.8,21-23 In a community sample of widow sand widowers, 46% of subjects with a syndromal level of CG did not meet the criteria for depression.21 Meanwhile, in a study sample of 96 patients suffering from CG, approximately 45% met the criteria for concurrent depression.24 Take, for example, the relationship of CG with depression. CG symptoms are strongly centered on the loss 9, whereas those of depression are much more generalised. Intense symptoms of separation distress, such as yearning for the deceased and trouble moving on without the deceased, an inability to accept the death, feeling detached from significant others since the death, and feeling bitter and agitated about the death, are unique to CG.21,22 CG patients may also lose interest in activities they formerly enjoyed with the deceased, but this effect is not the pervasive loss of interest as observed in depression. Additional CG symptoms that are not found in depression include strong wishes to reunite with the lost loved one, a desire to feel close to the deceased, intrusive or preoccupying thoughts about the deceased, and efforts to avoid reminders of the loss.9 Despite various differences between the two disorders, CG often co-occurs with depression, and the two disorders can exacerbate the symptoms of the other. The relationships between other disorders and CG follow the same principles and are not going to be described in detail here. Epidemiology Few studies on the epidemiology of CG are available. Complicated grief has been reported in approximately 9-20% of a population.13,27 Among clinical samples, a higher CG prevalence rate of 18.6% has been found in patients with unipolar depression29, and a prevalence rate of 24.3% has been reported for patients with bipolar affective disorder.30 A recent epidemiological study in a representative population - based sample 25 has shown that the prevalence of CG after major bereavement was 6.7%, while its prevalence among a general sample was 3.7%. While epidemiological studies on complicated grief have mostly been conducted in Western cultures, a study from Japan26 with data from 969 subjects revealed that 2.4% of the respondents had complicated grief and 22.7% had sub-threshold complicated grief. To the best of the author's knowledge, there is currently no published data from a representative sample in Hong Kong or mainland China. Risk factors Risk factors can be divided into individual personal factors, relationship-based factors, and factors related to the type, circumstances and consequences of the death. Consistent with the notion that CG stems from an attachment disturbance, individuals with weak parental bonding in childhood are more vulnerable. Studies have shown that people with a history of mood or anxiety disorders, insecure attachment in childhood9, and a history of childhood abuse or neglect 33 are particularly at risk. A close, dependent and confiding relationship between the survivor and the deceased are proven risk factors for poor bereavement adjustment, including an elevated risk for CG.31,32 In fact, widows with baseline conflicting spousal relationships have recorded lower levels of yearning than those with confiding and dependent marital relationships.31 Some types of loss, such as the loss of a child, the loss of a close life partner, and traumatic, suicidal or homicidal deaths, are particularly prone to instilling CG in the bereaved survivor. Circumstances such as failure to be present at the time of death or disagreements or conflicts with the provided medical care are also risk factors.9 Negative consequences of death, including any difficult problems related to the deceased person's possessions or death arrangements, poor perceived social support, negative or the perceived unsupportive attitudes of others may all heighten the risk for developing CG.9 Adverse outcomes Studies have shown that CG is associated with a heightened risk of both physical and mental impairment.8,34,35 A prospective cohort study of 4395 married couples aged 45-64 years in Scotland revealed that the bereaved participants had elevated relative risks of dying from cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, stroke, all cancers, smoking-related cancers (except lung cancer), and accidents or violence, even after adjustment for confounding variables.34 Patients with CG symptoms have an increased likelihood of depressive symptoms and major depressive episodes.21-23 CG has also been found to be predictive of reduced quality of life and poor mental health independent from depression and anxiety.35 Current treatment for CG To re-iterate, grief per se is not an illness or a problem. In most cases, it will heal naturally as do most uncomplicated physical wounds. Treatment is only reserved for those situations in which the natural healing process becomes derailed or impeded. Pharmacotherapy Pharmacological trials for CG are scarce, likely in part because CG is not yet included in the DSM / ICD as a formalised diagnosis. This current omission may have implications for clinical trials and limits pharmaceutical development targeting CG. To date, 4 open-label trials 36-39 of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors – (one trial on paroxetine and three trials on escitalopram) – have yielded positive results, either as a stand-alone treatment or in conjunction with psychotherapeutic interventions, providing preliminary support for their effectiveness in the treatment of CG. However, randomised controlled trials (RCT) are needed before more definitive conclusions can be drawn about their efficacy in ameliorating CG symptoms. Psychotherapy One highly effective treatment was introduced by Shear et al.24 The group conducted an RCT to test a manualised psychotherapy developed specifically for CG – the Complicated Grief Treatment (CGT). The study involved 95 participants divided into two arms and compared the efficacy of CGT with interpersonal psychotherapy. The results showed that the response rate was significantly greater for CGT (51%) than for interpersonal psychotherapy (28%), and the time to response was faster for CGT. All results were statistically significant.41 Other promising techniques included cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in an individual 40 or internet-based setting.42 Piper 's interpretative and supportive group therapies 43 were also found to be helpful. A recent meta-analysis concluded that the aforementioned treatment interventions yielded significant pooled standardised mean differences in favour of the specific CG intervention at both post-test and follow-up.44 The Common Mental Disorder Clinic and complicated grief treatment programme In Hong Kong, under the influence of traditional Chinese culture, people tend to be reluctant to talk about death-related issues. When encountering problems relating to bereavement, people often bottle-up and others might share only with a close relative who seldom has knowledge of when to seek help. Non-government organisations and social service centres in the community could provide grief counselling services. Clients with more complex or complicated bereavement problems could be referred to the primary health care system, i.e., a general practitioner or general outpatient clinic, from which further referrals would be made to a specialised psychiatric service if indicated. However, even in the tertiary health care system, i.e., psychiatric centres, targeted services for clients suffering from CG are lacking. The Common Mental Disorders (CMD) team in the United Christian Hospital, Department of Psychiatry, is committed to filling such gap. The team delivers specific psychotherapy to patients suffering from CG. The psychotherapeutic treatment has its roots in cognitive behavioural therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, problem solving and solution focus therapy techniques. It is highly structured, goal-directed and time limited (16-20 weekly sessions). The team provides such treatment using a multi-disciplinary approach, which comprises a psychiatrist, a psychiatric nurse, and an occupational therapist. In addition to psychotherapy, pharmacological treatment is also provided whenever indicated. Patients with the following characteristics are eligible for the service: 1) Age >18 years old; 2) Bereavement event happened > 6 months ago; 3) Bereavement-related psychological distress is the most important clinical problem at the point of time; 4) Scored >3 0 marks on the Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG). Patients eligible for the service then go through a joint interview session that involves the three disciplines mentioned. The purpose is to take a detailed history, to assess clinical needs, and to formulate problems and treatment plans for each patient in a multi-faceted manner. Once the care plan is formulated, the patient receives treatment from the three team members in a parallel and synchronized fashion so that psychological and behavioural treatment can be provided to the patient simultaneously. Another joint session with the patient will be conducted before treatment termination as an evaluation and round-up of the treatment. Figure 1 summarises the logistics of patient flow.

The role of each discipline on the team is briefly described below: The Multi-disciplinary Team The psychiatrist Apart from facilitating the assessment and formulation of each individual case using a holistic model of care, the psychiatrist focuses mainly on loss-oriented works which begin with an in-depth psycho-education of the process of normal grief, common misconceptions about grief, how grief can become stuck, as well as the ways to identify and overcome stuck points in CG. Sometimes, patients will become emotionally unstable during the treatment; hence, relaxation and grounding exercises are taught and practised at the very beginning. The patient is asked to make a daily record of the level of grief he/she experiences, including any associated circumstances or triggers. Such information can help in defining and working with the problems underlying the emotions. Exposure and narrative work play an important part in the treatment, from which patients are exposed to the most painful parts of the grief. The purpose is to assist the patients in processing the grief on both an emotional and cognitive level, to facilitate the integration of these inner processes, and to identify any dysfunctional thoughts, especially those relating to stuck points or hot spots during the narration. Any unhelpful thoughts are examined and challenged with the cognitive ehavioural approach. Transforming and fostering a continued bond with the deceased are promoted by working with memories, with or without using the empty chair technique that has its roots in gestalt therapy. This work is to facilitate an acceptance of the death and to empower the patient to start a new life whilst maintaining a continuous connection with the loved one. Goal setting is another core component of the intervention. The therapist assists the patient to explore and to work on personal or life goals, with stepwise progress to achieve goals, and to infuse hope and motivation for the patient to move forward. At the same time, it gives the patient the chance to reach out and to seek social support. Once the psychiatrist has explored a concrete goal plan with the patient, the psychiatric nurse and the occupational therapist work with the patient in practical ways. Occupational therapist While the psychiatrist focuses on grief-oriented works, the occupational therapist targets restoration-oriented tasks, which are combined into a treatment programme that follows the idea of the dualprocess model of coping with bereavement set forth by Stroebe et al.5 Under the shadow of CG, patients may have difficulty maintaining their life roles. Their occupational, social or personal functioning could be significantly affected, and prominent avoidance is also a common maladaptive coping strategy in CG patients. The occupational therapist focuses on the restoration of patients' daily functioning through assisting one with participation in purposeful and meaningful activities. This part of treatment includes a comprehensive assessment regarding the negative impacts of CG on the patient's functional abilities. Patients' assets, interests, personal goals, level of motivation and readiness for change are explored. The occupational therapist collaboratively works with the patient to establish treatment goals, determine realistic behavioural targets and formulate the action plan as well as the scheduling of planned activities. Treatment implementation includes reviewing daily activity schedules, exploring obstacles encountered, and working with the patient on possible ways to overcome difficulties. The activities are reinforced by sharing gains after an activity is successfully carried out. While the principle of activity scheduling is to encourage the patient to return to regular routines in a stepwise fashion and to participate in enjoyable activities with lower stress levels in the beginning, the ultimate aim is to facilitate self-expression and to process difficult feelings through creative activities. Adaptive coping strategies for anticipated difficult times, such as anniversaries or other important dates related to the deceased, are discussed in detail. Psychiatric nurse The role of the psychiatric nurse is complementary to that of the psychiatrist and the occupational therapist. Among the different models of nursing care, the McGill model is adopted due to its whole client-family care concept. It focuses on the patient-family relationship and aims to assist the patient in identifying expectations from the surviving family members and to explore the hidden potentials within the family system.45 Bereaved family members are expected to go through a role transition during the grief process, where complicated grieving and interpersonal relationship conflicts can arise. In this process, the goal of family nursing is to restore a healthy equilibrium and dynamic within the bereaved family. The intervention is implemented through family interviews. The nurse specialist plays the facilitator role by reconstructing the family dynamics. During the reconstruction, patients and family members are emotionally supported to express their needs and inner feelings in a safe and warm atmosphere. The therapist helps each family member to identify their own needs and strengths, and at the same time encourages them to show mutual acceptance and recognition. An open communication within the family is facilitated to maximize their potential to re-establish mutual trust. The purpose is to transform the prolonged sense of attachment loss and emotional sufferings to a sense of security, trust and connectedness to others. Patients are facilitated and encouraged to progressively regain confidence in their interpersonal competence and social functioning. Upon completion of the treatment, another joint multi-disciplinary session for termination is provided for the patient to review both the positive and negative aspects of the treatment, to promote meaning making from the death, prevent a relapse of unhelpful thoughts or behaviours especially during anticipated difficult times, and to solicit feedback from the patient.

Conclusion Considerable amounts of bereavement research in the past two decades have advanced our understanding of not only the course of uncomplicated grief as experienced by most mourners but also on how the grief process can be derailed and stalled in a minority of bereaved people. Not uncommonly, CG patients present with persistent, protracting acute grief symptoms lasting for years, or even decades, without respite. Given the progress made with respect to the identification of CG symptoms, evidence of its prevalence among bereaved people, and the development of interventions targeting this debilitating condition, there is a pressing need for health professionals to recognise and treat people suffering from this condition.

Adrian KH Sham, MBChB (CUHK), MRCPsych (UK), FHKAM (Psych), FHKCPsych

Associate Consultant Department of Psychiatry, United Christian Hospital Peter WC Tam, MSocSc (Mental Health) Advanced Practice Occupational Therapist Occupational Therapy Department, United Christian Hospital Gillian PK Wong, RMN (UK), MNur Advanced Practice Nurse Department of Psychiatry, United Christian Hospital Michael GC Yiu, MBBS, FRCPsych (UK), FHKAM (Psych), FHKCPsych Consultant and Chief of Service Department of Psychiatry, United Christian Hospital Correspondence to : Dr Adrian KH Sham, Department of Psychiatry, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR.

References

|

|