March 2010, Vol 32, No. 1 |

Original Articles

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

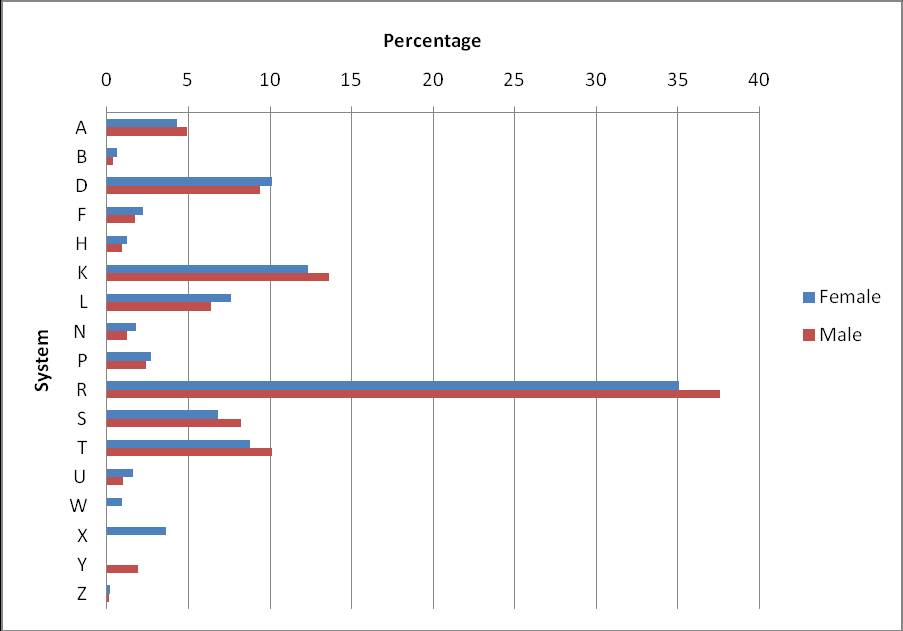

Hong Kong primary care morbidity survey 2007-2008Yvonne YC Lo盧宛聰, Cindy LK Lam林露娟, Tai-pong Lam林大邦, Albert Lee李大拔, Ruby Lee李兆妍, Billy Chiu趙志輝, Joyce Tang唐少芬, Billy Chui徐兆恒, David Chao周偉強, Augustine Lam林璨, Kitty Chan陳潔芝 HK Pract 2010;32:17-26 Summary Objective: To examine the morbidity pattern as presented to primary care doctors in Hong Kong such that service needs can be identified. Design: Prospective recording of all consecutive patient encounters in one week of each month from July 2007 to June 2008 using standardized forms. Subjects: All subjects consulting doctors who volunteered to participate in the study. Main outcome measures: Patients’ demographic data and health problems or diagnoses presented which were coded using the International Classification of Primary care (ICPC-2) Results: One hundred and nine primary care doctors took part in the study and identified 69,973 health problems / diagnoses. The mean number of health problems per encounter was 1.3±0.3. The respiratory system ranked top (36.2%) in the overall morbidity pattern by system, followed by cardiovascular system (12.8%), digestive system (9.8%) and endocrine system (9.3%). Psychological problems accounted for 2.6% of all problems encountered and were probably under-represented in this study. More than one-third of all health problems encountered were of chronic in nature. The five most common diagnoses were upper respiratory tract infections (26.4%), hypertension (10.0%), diabetes mellitus (4.0%), gastroenteritis (3.9%) and lipid disorder (2.7%). Immunization and health check-up accounted for 1.9% and 1.7% of all reasons for encounter respectively. Conclusion: Primary care doctors in Hong Kong are consulted for a diversity of health problems and a significant proportion of their workload is in the care of chronic diseases. Thus the challenge lies in enabling and empowering them in chronic disease care as well as mental health care as it appeared to be under-diagnosed in this study. The results are also useful in guiding the content of family medicine curriculum at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. Keywords: morbidity, primary care, general practice, Hong Kong Funding: This study was funded by the Studies in Health Services Grant (SHS-P-11), Food and Health Bureau, the Government of the HKSAR. 摘要 目的: 研究香港基層醫生所治療的患者的發病規律,從而確定服務需求。 設計: 採用標准表格對2007年7月至2008年6月每月某一周內所有患者連續就診的情況進行前瞻性記錄。 對象: 所有自願參與本研究的就診病人。 主要測量內容:患者的人口統計學數據,以及採用《基層醫療國際分類(ICPC-2)》編碼患者的健康問題或診斷。 結果: 109位基層醫生參與了此次研究,合共確定了69,973個健康問題/診斷。每次就診的健康問題均數為1.3?.3。呼吸系統問題佔各系統發病總數的首位(36.2%),其次為心血管系統(12.8%)、消化系統(9.8%)和內分泌系統(9.3%)。心理問題佔所有就醫門診的2.6%,本次研究就此類病人可能診斷不足。在就醫的所有健康問題中,三分之一以上為慢性疾病。最常見的五種診斷為上呼吸道感染(26.4%)、高血壓病(10.0%)、糖尿病(4.0%)、腸胃炎(3.9%)和血脂異常(2.7%)。免疫接種和體檢分別佔全部就診原因的1.9%和1.7%。 結論: 香港基層醫生要治療各種健康問題,慢性病在工作中佔較大比例,如何提供處理慢性疾病和診斷不足的精神衛生問題的能力成為一項挑戰。本調查的結果還有助於指導本科和研究生的家庭醫學課程內容的設置。 主要詞彙: 發病,基層醫療,全科醫療,香港 Introduction Most of the health problems that are brought to the attention of doctors are completely dealt with in primary care.1 Prevalence of such problems can reflect the general health of the community and noting the trends can serve as useful indicators on health care needs and health services planning. Like many Western countries, Hong Kong’s ageing population and changes in socioeconomic structure are likely to be coupled with changes in the primary care morbidity pattern.2,3 Chronic diseases and psychological problems are expected to be the major burden of illness of our population in the 21st Century.4,5 Practice-based morbidity survey provides a different type of information from population-based survey and it is more useful than data based on patient perceptions of illness for the planning of services. Morbidity as recorded by general practitioners not only reflect a relatively more accurate database for health care as doctors’ interpretation of illness is taken into account but it also identifies the needs in primary health care services. Four primary care morbidity surveys have been carried out in Hong Kong since 1980 and the last survey conducted in 1994 has already shown that general practitioners were increasingly taking care of patients with chronic illness.6-9 The Health, Welfare and Food Bureau (HWFB) consultative document “Building a Healthy Tomorrow — A Discussion Paper on the Future Service Delivery Model for our Health Care System” has identified the need to strengthen primary care services so that they can take up more responsibility in chronic disease management and preventive care.10 We need to know the type of health problems that are presented to and managed in primary care before we can forecast morbidity trends for the planning of health care services to meet current and future needs of the population. The main objective of the study was to describe the current morbidity pattern of patients as presented to primary care doctors in Hong Kong. Methods This was a cross-sectional study with prospective recording of all patient encounters that took place in various primary care services in a specified week of every month during the year between July 1, 2007 and June 30, 2008. We invited members of the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians, doctors working at public general outpatient clinics, university health services, general outpatient clinics of private hospitals and clinics of non-governmental organizations to take part in this study. Letters were sent to doctors explaining the objectives and describing the proposed study. Participation of doctors was entirely voluntary. In order to ensure that data was collected evenly throughout the study period, the 12 weeks of data collection was divided into four quarters and each doctor could choose to take part in one week of one or more quarters. Standardized recording sheets were provided to document all consecutive patient encounters during each data collection week including age, sex, method of payment at the time of consultation, health problems or diagnoses, and management activities such as number of drugs prescribed, whether investigation was ordered, referral made and whether any preventive activities were performed. Participating doctors were given the option of either entering the health problems or diagnoses as free text or as codes according to the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC-2) developed by the World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA).11 Primary care doctors are often the first point of contact of care and very often they encounter problems at an early, undifferentiated stage where a definite diagnosis cannot be made. The ICPC coding is specially designed for primary care as it consists of seven components under each system: symptoms and complaints, diagnostic and preventive procedures, results, administrative, referrals and other reasons for encounter, and diagnosis or disease. Each participating doctor was given a copy of the English version of the ICPC-2 pager as reference with common health problems highlighted. They were also invited to attend any of the three identical ICPC training workshops that were conducted in June and July 2007. Transcription of free-text entry of diagnoses was performed by two Specialists in Family Medicine who were experienced with the classification. Doctors’ demographic data and type of practice were also recorded on a separate form. The outcome measures reported on this paper were the health problems or diagnoses managed in all patient encounters during the study period. The data was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Science Version 16 and the occurrence of different types of health problems or diagnoses were expressed in terms of percentage distribution. Results One hundred and nine primary care doctors took part in the study contributing to a total of 280 doctor-weeks of data collection. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of participating doctors. The majority of doctors were aged below 45 and there were more male than female doctors. Almost two-thirds of the doctors had ten or less years of working experience in general practice. More than 70% of the doctors worked in the private sector. There were 52,337 patient encounters of which 38,414 (73.4%) were recorded in the private sector and 13,923 (26.6%) in the public sector, and the total number of health problems or diagnoses collected was 69,973. According to a general population study on service utilization pattern in Hong Kong in 2007-2008,12 of those who sought Western medicine primary care service in their last consultation, 79.3% consulted private general practitioners while 20.7% attended the public general outpatient clinics. As the public sector was over-represented in our survey, our data was weighted to simulate the general population private and public primary care service utilization ratio.12 This was done by dividing 79.3% by 73.4% to obtain the weighting factor of 1.08 for the private sector data. Similarly, a weighting factor of 0.78 was calculated for the public sector data. The frequency distributions of the health problems before and after population weighting were compared and found no major differences in their percentages and their ranking, thus we presented our findings with the weighted data. The mean number of patient encounter per doctor per week was 183.5 (standard deviation 104.1) and median was 169.5. The mean number of health problems managed per doctor per week was 239.3 (standard deviation 145.0) and the median was 210. Population ageing is evident in Hong Kong as compared with ten years ago as reported by the Census and Statistics Department of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.13 Table 2 shows the age-sex distribution of the study population and the general population of Hong Kong in 2007. The age distribution of our study population was fairly similar to that of the Hong Kong population except we had a smaller adolescent and a larger elderly population which can be explained by the natural occurrence of diseases in these two populations. Figure 1 shows that both genders have similar ranking order in morbidity by system. Figure 1: Morbidity distribution by system and by gender

Table 3 shows the overall morbidity pattern by system and by age group. Overall, respiratory problems were encountered most commonly (36.2%) followed by cardiovascular (12.8%), digestive (9.8%), endocrine (9.3%) and skin problems (7.4%). Psychological problems accounted for only 2.6% of all problems. Although respiratory problems ranked top in all age groups below 65 years, it only came second (18.9%) in the elderly group following cardiovascular problems (30.7%). Respiratory, cardiovascular, endocrine, digestive and musculoskeletal problems were most commonly encountered among both elderly and adult groups. Respiratory, skin, digestive, general and musculoskeletal problems were most commonly encountered among the adolescent and young adult groups while the paediatric group commonly presented with respiratory, skin, general, digestive and eye problems. A diversity of health problems were consulted for in the study. Seven hundred and eighty five health problems were reported in the whole study with 13 being commonly presented at a frequency of no less than 1%, 93 at a frequency of no less than 0.2% and 203 at a frequency of no less than 0.1%. As shown in Table 4, six different health problems accounted for top 50% of all problems encountered in our study population, 37 for top 75% and 53 for top 80%. One hundred and ninety health problems accounted for the top 95%. Upper respiratory tract infections (26.4%) were commonest followed by hypertension (10.0%), diabetes mellitus (4.0%), gastroenteritis (3.9%) and lipid disorder (2.7%). Anxiety and depression accounted for 0.8% and 0.7% of all problems respectively. Preventive care such as immunization and health check-up accounted for 1.9% and 1.7% respectively. Table 5 shows the top ten ranking by percentage distribution of health problems by age groups. Upper respiratory tract illnesses were commonest in all age groups except in the elderly group in which it only came second (10.8%) following hypertension (23.7%). Chronic diseases were prevalent in the elderly group and accounted for more than 50% of all presenting problems. Hypertension, diabetes mellitus and lipid disorder together accounted for almost 25% of all health problems in the adult group. Hypertension ranked ninth in the young adult group accounting for 1.4%. Although not shown in the table, diabetes mellitus accounted for 0.6%, ranking sixteenth in the young adult group. Table 1: Demographic characteristics of participating doctors

Table 2: Demographic distribution of study population and Hong Kong Population

Table 3: Morbidity pattern by system and by age group

Table 4: Top 80% health problem

Table 5: Top ten ranking by percentage distribution of health problems in each age group

Over 70% of all health problems in the paediatric group and over 50% in both adolescent and young adult groups were of acute in nature. In terms of psychological problems, anxiety accounted for 1.0% in young adult (ranking twelfth), 1.1% in adult (ranking tenth), and 0.6% in elderly group (ranking fifteenth) while depression accounted for 0.7% in young adult (ranking fifteenth), 0.9% in adult (ranking twelfth) and 0.5% in elderly group (ranking sixteenth). In terms of preventive care, immunization ranked within the top ten in all age groups except the elderly group (1.3%). Physical check-up ranked within the top ten in the young adult (2.7%) and adult (1.9%) groups, but accounting for only 0.5% in the elderly group. Discussion The information gathered in this study is different from that obtained in the Thematic Household Survey14 which provides data on self-reported illness and includes those for which the patients did not contact any primary care doctor or had consulted other types of health care services. Although it is generally accepted that the data collected does not reflect all morbidity in the community, it nevertheless indicates health needs and demand in such a setting. The results of this study provide the most comprehensive information currently available about the people consulting Western primary care services in Hong Kong and the doctors’ interpretation of their health problems. The sample covered is sufficient to include a wide range of problems as more than 50,000 patient encounters and more than 69,000 health problems were recorded over a one-year period. The finding of no major difference between weighted and non-weighted data suggests that our data is robust and results are representative of Western primary care services in Hong Kong. As mentioned previously, six different health problems accounted for top 50% of all problems encountered and 190 health problems made up for top 95%. On average, each doctor in this study managed about 240 health problems per week. Based on the frequency distribution of various types of health problems obtained from this study, 19 health problems can be considered as common since they were encountered more than once a week (cut-off frequency distribution at 0.8%) while 93 can be considered as important since they were encountered more than once a month (cut-off frequency distribution at0.2%). These results have important implications in the planning of undergraduate medical curriculum as well as postgraduate training in family medicine as these are the health problems that primary care doctors should be able to manage unusually well. Ageing of the Hong Kong population is evident and chronic diseases, mainly hypertension, diabetes mellitus and lipid disorder, are common among the adult and elderly population in our study. The proportion of consultations for hypertension, diabetes mellitus and lipid disorder in our study were 10.0%, 4.0% and 2.7% respectively. These diseases only accounted for 6.6%, 2.6% and 0.4% respectively of the total health problems encountered in the previous survey.9 Patients with these chronic conditions are liable to develop complications and this is evident in the elderly population in which cerebrovascular disease and ischaemic heart disease accounted for 2.4% and 1.7% of all health problems, ranking fifth and eighth respectively. However in the previous survey, ischaemic heart disease accounted for 0.5% of the total health problems encountered ranking thirty-two while cerebrovascular disease was not even within the top 80%. In the young adult group, hypertension accounted for 1.4% of all health problems encountered in this study compared with 1.2% in the previous survey. Diabetes mellitus accounted for 0.6% of all health problems encountered in this age group, but its frequency in this age group was not reported in the previous survey. These results signify the importance of raising public’s awareness of such chronic diseases, promotion of healthy lifestyle, early detection and continual monitoring of these diseases, early detection of complications and provision of support services to patients who develop complications. The proportion of consultations for allergic rhinitis and asthma in our study were very low compared to a local review in 1993.15 This review found that the prevalence of hayfever and perennial rhinitis was 1.6% and 14.0% respectively in adults, 15.2% and 21.9% respectively in school children; that of asthma was 2% in adults and up to 8% in school children. Such conditions have similar presentations as upper respiratory tract infections and acute bronchitis, thus making a diagnosis can often be difficult in only one episode of care as doctor-shopping is common in Hong Kong.16 This often leads to misdiagnosis, under-diagnosis and even under treatment of these conditions. Patients with these conditions may also be under the care of specialists thus these figures may not represent the true prevalence. Furthermore, the prevalence by consultations is also influenced by the relative frequency of consultations for other illnesses in such study. The proportion of consultations for anxiety and depression in our study were 0.8% and 0.7% respectively. These figures were very low in our study and in particular depression among the elderly when compared with the high prevalence of mental health problems reported in recent local and overseas studies.17-20 Such low percentage can be relative than absolute as there may be higher number of consultations for other health problems. However, it can also be explained by the common phenomenon of psychosomatization in the Chinese population leading to under diagnosis of mental illnesses.21 This is supported by a local study which found that patients presented to primary care initially with a wide variety of somatic symptoms before depression was diagnosed and disclosure of psychological symptoms on further exploration.22 Patients’ health belief and normalizing style of symptom attribution, which is a tendency to minimize the importance of symptoms, can also result in low detection rates of anxiety and depression.23 People may also be less inclined to consult for psychological problems because they may think doctors mainly care for physical illnesses. Another possible reason is the doctor may choose not to make a diagnosis of a mental health problem because of stigma and management implications. Further studies are warranted to reveal the true prevalence of anxiety and depression in primary care in Hong Kong. Immunization and physical check-up together accounted for 3.6% of all reasons for encounter showing that primary care doctors were taking up a significant role in preventive care. It is observed that health check-up accounted for 2.7% of all encounters in the young adult group ranking fourth. This can be due to the requirement for medical examination for various reasons such as employment, overseas visa application and insurance application in which case would be more of an administrative reason than a medical reason. On the other hand, if the purpose of health check-up is purely for screening in apparently healthy individuals, then such practices should be explored further for their cost effectiveness. This paper only reports on the current morbidity pattern of patients attending various primary health care services in Hong Kong. With the available data, we can also compare the morbidity pattern of patients in both private and public primary healthcare sectors and to provide an indication of the care delivered to patients in terms of various management activities which will be discussed in other papers. Limitations Under the Hong Kong health care system, service utilization pattern is complex as people are free to choose their own doctors and there are various types of primary care services available including specialist care. This pattern may influence estimates of symptom prevalence and disease frequency. We aimed to recruit doctors from various types of practices, including private solo practice, group practice, private hospitals, non-governmental organizations, but we may not have other types of general practitioners or specialists who may also act as primary care physicians taking part in the study. Although our approach is subject to selection bias which can affect the outcomes of the study and does not draw definite conclusions with regard to the population level, it nevertheless provides some useful data about primary care in Hong Kong. This can be improved by building a primary care research network to allow the best recruitment of primary care doctors for similar studies in the future. The participating doctors of this study were a volunteered group of primary care doctors in Hong Kong and it was emphasized to them that information of all consecutive patient encounters was to be recorded during data collection weeks. Although it might be possible that some may not totally comply with the study protocol, there were no reasons to suspect that they would under-report in purpose as their participation was entirely voluntary. Studies of this kind depend on the reporting behaviour of the doctors unless direct access to medical records was possible. We have attempted to minimize the diagnostic coding discrepancy by distributing the ICPC-2 pager, highlighting common health problems, providing explanatory notes and conducting three ICPC workshops. However some variations between the diagnoses made by different doctors, or by the same doctor on various occasions were bound to occur as described by Crombie et al.24 Conclusions Our study has reflected the diversity of health problems seen by primary care doctors and should provide a glimpse of what primary health care services our population needs. It is evident that primary care doctors are taking care of an increasing load of patients with chronic diseases and as in other developed countries, younger people being consulted for chronic diseases are increasing. Thus the challenge is how to better enable primary care doctors in preventing, detecting and managing chronic diseases. The possibility that mental health problems are underdiagnosed warrants further study, and if this is the case the challenge is how to improve the detection and care of these patients in primary care. Our results should also be useful in guiding the content of undergraduate medical curriculum and family medicine vocational training programmes. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank all the doctors who contributed in the study, Ms Mandy Tai and Mr. Carlos Wong for providing research assistance. Ethical approval: The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster. Yvonne YC Lo, MBChB(CUHK), FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM(Family Medicine) Cindy LK Lam, MBBS(HK), MD(HK), FRCGP, FHKAM(Family Medicine) Tai-pong Lam, PhD(Syd), MD(HK), FRCP(Glas), FHKAM(Family Medicine) Albert Lee, MBBS(Lond), MD(CUHK), FHKAM(Family Medicine), FFPH(UK) Ruby Lee, MBBS(HK), FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM(Family Medicine) Billy Chiu, MBBS(HK), FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM(Family Medicine) Joyce Tang, MBBS(NSW), FRACGP, MPH, FHKAM(Family Medicine) Billy Chui, MBChB, FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM(Family Medicine) David Chao, MBChB(Liverpool), MFM(Monash), FRCGP, FHKAM(Family Medicine) Augustine Lam, MBBS(HK), FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM(Family Medicine) Kitty Chan, MBBS(HK), MRCGP, FHKCFP, FHKAM(Family Medicine) Correspondence to: Dr Yvonne YC Lo, Family Medicine Unit, HKU, 3rd Floor, Ap Lei Chau Clinic, 161 Main Street, Ap Lei Chau, Hong Kong SAR. Email: yyclo@hku.hk References

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||