|

September 2009, Volume 31, No. 3

|

Update Articles

|

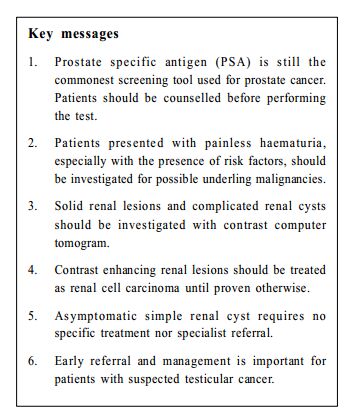

Urology Update 2 - management of uro-oncology and associated urological symptomsChi-fai Ng 吳志輝, Man-tat Ng 吳文達, Sidney KH Yip 葉錦洪 HK Pract 2009;31:128-132 Summary Prostate cancer is one of the commonest cancers found in the male population. The benefit of using prostate specific antigen (PSA) in its screening is still controversial and practitioners need to be aware of the natural history, potential false positive and negative associated with its use and counsel patients before the screening test. Painless haematuria, especially with the presence of risk factors should be investigated properly for possible underlying malignancies. Simple renal cysts could be managed conservatively. But complicated renal cysts or solid renal lesions should be investigated with contrast computer tomogram for possible malignancies. Testicular swelling with suspicion of malignancies should be referred and investigated promptly as early diagnosis and management could improve the prognosis. 摘要 前列腺癌是男性最常見的癌症之一。用前列腺特異性抗 原(PSA)進行篩查的益處目前仍有爭議。醫生應瞭解病史,採 用此方法可出現假陽性和假陰性的結果,在篩查前應為對患者 提供咨詢。無痛性血尿,特別是存在危險因素時,應做適當檢 查,確定是否存在惡性腫瘤。單純性腎囊腫可做保守治療,但 複雜的腎囊腫或實性腎病變應採用電腦掃描顯影排除惡性腫瘤 的可能。睾丸腫脹並懷疑為惡性者應迅速進行轉介和檢查,因 為早期診斷和治療可以增加治愈的機會。 Introduction Urological cancers are common, especially in the male population. From the Hong Kong Cancer Registry, prostate cancer and bladder cancer are now the fourth and the seventh most commonly diagnosed cancer in male population, respectively.1 Therefore there is increasing demand for family physicians to know the basic approach to some of those urological complaints that may be related to uro-malignancy. In this update, we will focus on four issues: (1) The role of prostate specific antigen (PSA) s creening for prostate cancer, (2) Management of haematuria, (3) Management of incidental renal lesion and renal cyst, and (4) Management of testicular mass. Prostate cancer & PSA testing In developed countries, prostate cancer is the second commonest cancer, and the third commonest cause of death from cancer in men.2 In Hong Kong, it is the fourth commonest cancer in males, after lung, colorectal and liver cancer, with an annual incidence approaching 1000 cases per year. 1 The rapid rising incidence of prostate cancer in Hong Kong is especially alarming, with about 2.5 times increase in incidence in the past ten years. This substantial rise is probably related to the introduction of screening with PSA, the increased public awareness and also the westernization of life-style3,4 Prostate cancer has several characteristics that make it a suitable candidate for developing a s creening programme. These characteristics include the high disease incidence, available curable therapy for early stage of disease and in most cases a long natural course, which gives a window of opportunity for screening. Digital rectal examination (DRE) has little value as a screening test.5 The main screening test developed for prostate cancer is the serum concentration of PSA.screening in prostate cancer management. There are evidences suggesting that PSA screening lead to decrease in advanced incurable disease, mortality rate,6,7 and the proportion of locally advanced disease in prostatectomy specimens, 8 etc However, there is always concern about the risk related to the increased number of biopsies, overdiagnosis and over-treatment of indolent cancer, and treatment-related morbidity, etc. There are currently several large scale studies, including the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer9 and Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial,10 being carried out in Europe and the US which will give further light on the real benefit of PSA screening. Currently there is still no standard recommendation of PSA screening in Hong Kong. It is essential to have some basic understanding about prostate cancer before we discuss practical advice on PSA testing. Prostate cancer is a slow growing disease and the prevalence increases with patients' age. Although autopsy based prevalence is 80% by the age of 80 years,11,12 the risk of actually dying from prostate cancer is quite low. Majority of prostate cancer are slow growing tumours which may not cause any symptoms, or even mortality, to the patients. However, in younger patients (less than 65 years old) with prostate cancer of intermediate to high grade disease, there is a higher chance for them to suffer from the disease at some time in their life. Therefore, it is generally agreed that PSA screening should only be offered to patients with life expectancy of at least 10 years and also fully counselled about the implication of the test.13 The counselling should include the following facts,

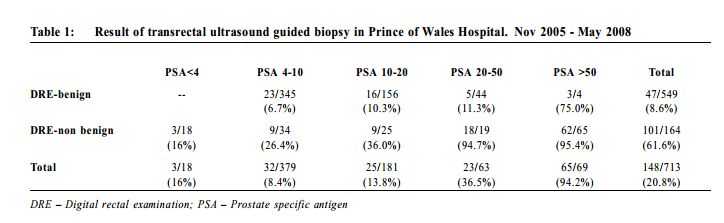

The usual cut-off point for serum PSA level is 4 ng/dL, though some early tumour can be missed by this cut-off level.14 The natural history of this early cancer is still uncertain, especially if further regular monitoring of PSA level will be performed.15 Therefore, for suitable patients, yearly PSA monitoring may be suggested to monitor the serial changes of PSA level. In general, the pick up rate of prostate cancer increases with PSA level. In Prince of Wales Hospital, about 700 patients received transrectal ultrasound guided biopsy in the past two and a half years. Their pathology results are summarized in Table 1. The level of PSA level is closely related to the chance of positive prostatic biopsy. Also the co-existing abnormal digital rectal examination findings will further increase the chance of diagnosis of prostate cancer. This summary may provide some guidance for the interpretation of the serum PSA level for local Hong Kong population.

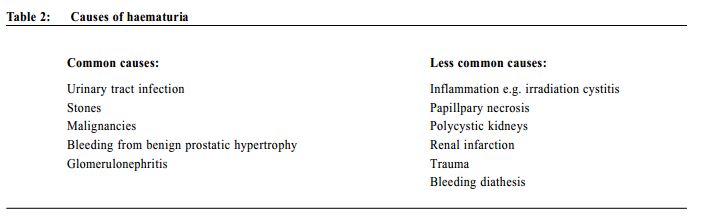

Management of haematuria Haematuria, either macroscopic or microscopic, could be due to various causes. (Table 2) In the general population, urinary tract infection is probably still the commonest cause of haematuria and could be safely treated by family physicians. However, urological malignancies, especially bladder cancer, are conditions that we should not miss in the initial ass essment. Therefore, it is of utmost importance that family physicians are aware of patients who are at risk of having malignancies, and perform baseline investigations, before referral to urologists. Clinical judgment is important as there are no simple rules to exclude possibility of malignancies. We should try to identify possible risk factors during history taking, physical examination and investigations.

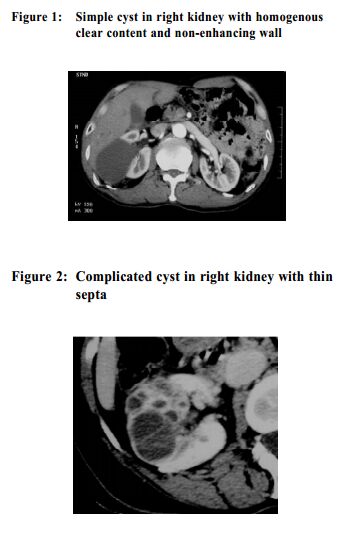

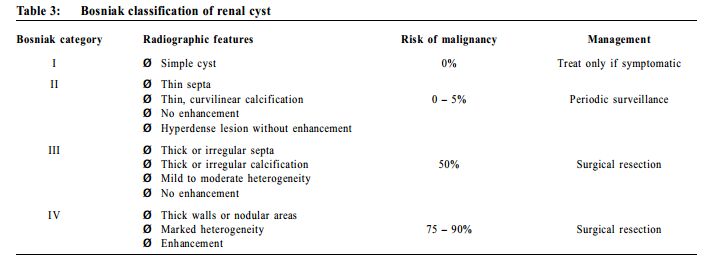

commonest cause of haematuria and could be safely treated by family physicians. However, urological malignancies, especially bladder cancer, are conditions that we should not miss in the initial ass essment. Therefore, it is of utmost importance that family physicians are aware of patients who are at risk of having malignancies, and perform baseline investigations, before referral to urologists. Clinical judgment is important as there are no simple rules to exclude possibility of malignancies. We should try to identify possible risk factors during history taking, physical examination and investigations. Physical examination may reveal the presence of tumour mass. Abdominal examination may reveal a ballotable mass / pelvic mass. Investigations should be performed in those patients with risk factors. In the setting of family physicians, the followings are advisable: (1) urine for culture and cytology, (2) plain radiography of kidney-ureter-bladder view (KUB) and (3) other radiological imaging including ultrasonography (USG) of abdomen and pelvis / intravenous urogram (IVU) / CT urogram. Urine for cytology is a specific (>=98%) but not a sensitive test (as low as 20-30% in case of low grade tumours, improve up to ~80% in high grade tumours). Multiple samples (up to 3) could improve the yield. For patients older than 40 and/or with other risk factors, cystoscopic examination of bladder is necessary to rule out bladder cancer. In order to avoid unnecessary delay in management, it is important to indicate in the referral that the patient harbours potential malignancy as backed up by risk factors and baseline investigation results, so that the patient could be properly triaged by specialists. Management of incidental renal lesion With the increasing accessibility of imaging facilities and increasing health awareness, more and more people will have imaging studies during body check-up or investigations of abdominal symptoms. This may partly explain the rising incidence of renal cancer in recent years,16,17 especially small size lesions.18 For solid renal lesion, contrast computer tomogram is necessary to characterize the lesion. Benign solid renal lesion is uncommon. Angiomyolipoma is the commonest benign lesion which has characteristic fat composition demonstrated in computerized tomogram. For other contrast enhancing mass, it should be managed as renal cell carcinoma (RCC) until proven otherwise. Currently, surgical treatment is still the only curative treatment for RCC. Laparoscopic radical nephrectomy has already been accepted as the standard treatment for localized RCC.19, 20 For small size lesion (less than 4cm), partial nephrectomy is another option with curative rate comparable to traditional radical nephrectomy. 21 Another common renal lesion that can be identified by imaging is renal cysts. Most renal cysts are acquired and sporadic. Familial causes like polycystic kidneys may also be encountered by family physicians, which is asymptomatic, though large renal cyst could present as dull loin pain. Acute pain could also occur in the setting of acute haemorrhage into cyst or infection. But gross haematuria is rare. Renal cysts are readily picked up by ultrasonography. It could be classified as simple (Figure 1) or complicated cyst (Figure 2), following the Bosniak classification (Table 3).22 If USG is suggestive of a complicated renal cyst, further characterization by contrast computerized tomogram is mandatory.

Asymptomatic simple renal cyst requires no treatment. Reassurance should be given and no specialist referral is required. In case of symptomatic simple cyst or a complicated renal cyst, referral to urologist is advised. For large and symptomatic cysts, percutaneous aspiration with injection of sclerosing therapy or surgical marsupialization may be performed. For type III or type IV cysts, surgical excision, either partial nephrectomy or total nephrectomy could be performed to remove the lesion and allow formal pathological assessment of the lesion. Management of testicular swelling Testicular cancer is not very common with an average of less than 60 new cases per year in Hong Kong from 1996 to 2005, and nearly 80% of patients are less than 50 years old.1 Majority of patients will present with painless scrotal swelling. However 10-20% may have some mild pain or even acute pain due to sudden tumour bleeding. The patient may have a history of testicular abnormalities such as maldescended testis, testicular atrophy, inguinal hernia and infertility.23,24 1-3% of patients with testicular germ cell tumours reported an affected first-degree relative.25,26 Physical examination usually reviewed non-tender hard testicular lesion with or without associated hydrocele. In advance cases, there may also be central abdominal mass which suggests retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. Differential diagnoses include epididymo-orchitis, simple hydrocele, testicular trauma or torsion. However, the diagnosis can be easily confirmed with scrotal ultrasound. Serum markers such as alpha-fetoprotein, beta-hCG are helpful tools for diagnosis. The main problem in management is the delay in diagnosis, which can be resulted from the patient's embarrassment and hence delay in presentation or delay in investigations by physicians. Early diagnosis of testicular cancer is crucial since the doubling time of testicular tumours is estimated to be 10 to 30 days.27 Although effective chemotherapy and radiotherapy have improved the survival rates for all stages of disease, an earlier stage of disease at diagnosis still carries a better long-term prognosis. Therefore, for patients suspected to have testicular cancer, arrangement of appropriate investigations and early urological referral is important to improve the outcome of these patients.

Chi-fai Ng, MBBS (HK), FAMS (Urology), FHKAM (Surg)

Associate Professor Sidney K H Yip, MRCGP(UK), FHKAM (Fam Med) Professor Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Chinese University of Hong Kong Man-tat Ng, MBBS(HK), FRCSE (Urol), FHKAM (Surg) Associate Consultant Department of Surgery, North District Hospital. Correspondence to : Professor Chi-fai Ng, Department of Surgery, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, NT, Hong Kong SAR.

References

|

|