|

September 2009, Volume 31, No. 3

|

Case Report

|

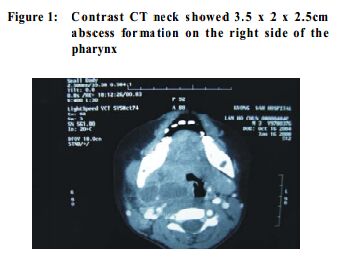

Abdominal pain secondary to peritonsillar and parapharyngeal abscess in a childI M C Chan 陳美貞, D K Ng 吳國強 HK Pract 2009;31:140-144 Summary Abdominal pain in young children is a non-specific complaint. It can be a symptom of gastrointestinal problems such as gastroenteritis and acute appendicitis. However, it is also a well reported symptom in acute tonsillitis. We present a case of a 3-year-old boy with right peritonsillar and parapharyngeal abscess with initial misleading presentation of abdominal pain. Early diagnosis of acute tonsillitis in young children having fever and abdominal pain may prevent serious complications. Early contrast computer tomography may play an important role in diagnosis and facilitate management. 摘要 在兒童,腹痛是一種非特定性的徵狀。它是腸胃炎或急 性闌尾炎等腸胃性疾病的常見病徵,但它亦被確認為急性扁 桃腺炎的病徵之一。文中病例介紹一個三歲患有扁桃腺周圍 和咽喉旁膿腫的男童。其初期病徵是具有誤導性的腹痛。及 早為發燒和腹痛的幼童診斷急性扁桃腺炎可防止嚴重併發症 的出現。對照性計算機¢æ 線斷層掃瞄術能在早期診斷和治療 方面擔當重要角色。 Introduction Parapharyngeal, retropharyngeal and peritonsillar abscesses are deep neck space infections which are secondary to contiguous spread from local sites. An increased incidence of head and neck abscesses in children was reported over the past few years, probably related to the increased virulence of the pathogens.1 Children with deep neck space infection tend to have a more subtle presentation compared to adults because they could not express their symptoms well. A high index of suspicion is very important in the early diagnosis of deep neck infection. Case A 3-year-old boy with good past health presented with mild coryzal symptoms to his general practitioner. Upper respiratory tract infection was diagnosed and some cough mixture was prescribed. Two days later, he had vomiting, abdominal pain and sore throat. The same general practitioner prescribed him a 3-day course of oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, ibuprofen and cough mixture. However, his abdominal pain persisted. The general practitioner then treated him as gastroenteritis with hyoscine and ibuprofen. Ten days after his symptom onset he was admitted to our unit for further management. Upon admission, his general condition was good and the body temperature was 37.5 o C. Apart from a congested throat and a mobile firm tender right cervical lymph node (1cm in diameter), no obvious tonsillar swelling nor exudates were noted. He developed neck pain and poor feeding one day after admission. The following day, his sore throat and neck pain increased, coupled with drooling of s aliva and difficulty in opening his mouth. There was no recent dental procedure done or history of fish bone ingestion. Physical examination revealed a toxic looking child. His neck was held at an extended position. He was reluctant to move his neck or to receive neck examination because of the neck pain. A diffuse firm and tender swelling was palpable below the angle of right jaw. Fluctuation could not be demonstrated due to the pain. Inside the oral cavity, a prominent smooth mass was found lying over the right side of the soft palate and extending to the area anterior to the right tonsil. No exudates were seen over the mass or the tonsils. His uvula was central. No stridor or any respira tory distress was noted. Peritonsillar abscess was suspected at that time. Neck x-ray showed loss of lordosis, no increase of prevertebral soft tissue and no air-fluid level were seen. Computer tomography (CT) of the neck with contrast showed a 3.5 x 2 x 2.5cm abscess on the right side of the pharynx (Figure 1). Total white cell count was elevated (28.3 x 10^9/L) with neutrophil (23.4 x 10^9/L) predominance. C-reactive protein was also raised to 98 mg/L. Anti-streptolysin O titre (ASOT) and Monospot tests were negative.

Emergency transoral incision and abscess drainage was performed with prior empirical in travenous amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and metronidazole. Six milliliter of pus was collected over the right peritonsillar and right parapharyngeal space at the oropharyngeal level with extension to the medial surface of the ramus of right mandible. Post-operatively he required ventilation; nevertheless, he was successfully extubated one day after the operation. Pus culture yielded staphylococcus aureus, streptococcus viridian and streptococcus milleri which were s ensitive to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and erythromycin. Appropriate antibiotics were subsequently administered. Discussion The curren t cas e illustrates one o f the many presentations of bacterial tonsillitis. Although children with tonsillitis usually present with fever, sore throat and swollen tender cervical lymph node, abdominal pain and vomiting are also well reported symptoms. Therefore, the diagnosis of tonsillitis should be borne in mind when one is faced with fever and abdominal pain in a child who may not be able to express co-existing sore throat. Sometimes, it is difficult to differentiate common upper respiratory tract infections from deep neck infection in the early stage. However, a recent history of dental procedure or fish bone ingestion could alert us. In addition, children with deep neck infections may have high fever, agitation, oropharygneal abnormalities prior to the development of neck mass or stiffness. The clinical pres entation of peritonsillar and parapharyngeal abscesses is similar to other deep neck infections. They always present with a neck mass, high fever, cervical lymphadenopathy, poor oral intake and neck stiffness irrespective of ages. Patients younger than four years, compared with older children, were more likely to present with agitation, cough, drooling, lethargy, oropharyngeal abnormalities, respiratory distress, retractions, rhinorrhoea, stridor and trismus.2 Peritonsillar abscess is usually confined by the tonsillar capsule. However, once infection breaks through to the parapharyngeal space and beyond, parotid swelling and septicaemia may follow. Peritonsillar abscess (or quincy) is the most common deep neck space abscess. It starts with acute follicular tonsillitis followed by peritonsillitis and finally abscess formation. It is noteworthy that an abscess could form without any preceding history of tonsillitis.3 Parapharyngeal abscess is the second commonest deep neck space abscess. The parapharyngeal space communicates with all major fascial spaces in the neck. Ext en sion s in to this sp ac e from p eriton sill ar or submandibular abscess may occur. Possible aetiologies include odontogenic problems, tonsillitis and peritonsillar abscess. Blood tests including complete blood picture with differential count, C-reactive protein, antistreptolysin O titre and blood culture are useful in making a diagnosis. A plain lateral neck radiograph is useful to look for retropharyngeal abscess. Radiological features may include prevertebral soft-tissue widening, air in soft tissue or evidence of vertebral osteomyelitis. Normal retropharyngeal soft tissue width in children is reported as 2 -7mm at the anterior inferior aspect of C2 (retropharyngeal),5-14 mm at the anterior inferior aspect of C6 (retrotracheal). These widths in adults are 1-7 mm and 9-22 mm respectively.3 Cervical ultrasound imaging is useful in identifying fluid-filled spaces and also in detecting jugular vein thrombosis. Ultrasound doppler improves the vascular definition of a lesion or its adjacent structure.3 Ultrasound also plays an important therapeutic role, since ultrasound-guided percutaneous catheter drainage of both parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal abscesses can be performed. However, the sensitivity of ultrasound is limited to large-volume abscesses. Also it is less useful in evaluating a deeply embedded lesion like peritonsillar abscess. 3 Computer tomography with contrast enhancement is the single most sensitive and specific imaging study for evaluating deep neck abscesses. The sensitivity and specificity of CT contrast range from 68-100% and 45-57% respectively.4-6 The positive predictive value and negative predictive values were 7 1% an d 5 3% respectively.5 Features of a true abscess are a thick enhancing rim with a central low-density zone. A multiloculated appearance with central air is also suggestive of an abscess. A less homogeneous radiolucent central region may represent phlegmon (i.e. purulent inflammation and infiltration of connective tissue) but not a true abscess.3 Contrast CT is more reliable than ultrasound because the surrounding soft tissue, bony structures, internal jugular vein and mediastinum can be illustrated clearly. Therefore the associated complications and extent of the disease can be seen. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also be used to demonstrate an abscess in the neck. Lesions have low signal-intensity on T1-weighted images, high signal intensity or heterogeneous on T2-weighted images. The addition of gadolinium provides enhancement of the abscess wall. Yet, these findings are less sensitive than CT characteristics and provide no additional benefit in the differentiation of abscess from phlegmon. The advantage of MRI in the evaluation of fascial space infections lies in its multiplanar capability, especially using the sagittal plane to evaluate the retropharyngeal space.3 The majority of deep neck infections are caused by organisms from normal oral flora. Normal colonization changes to virulent infection when mucosal barriers break down, which occurs during pharyngitis, odontogenic infections and trauma. Fascial space abscesses are frequently mixed aerobic and anaerobic organisms, although anaerobes predominate. The commonest anaerobes is olated include Peptostreptococcus, Fusobacterium and Bacteroides. The predominant aerobic organisms are Group A Streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes), Streptococcus milleri group organisms, Staphylococc us aureus, Streptococci viridans and Haemophilus influenzae.1-3, 7 The most common single is olates from deep neck infections are aerobic streptococci.7 Group A streptococcal infections have been increasingly reported over the last decade because of the increase in virulence of S. pyogenes. It is associated with M protein types M1 and M3. The M proteins efficiently prevent phagocytosis of S. pyogenes by inhibiting interaction with complement. 8 The management of peritonsillar, parapharyngeal and retrophargngeal abscesses is similar. Initial empirical intravenous antibiotics covering Gram positive and anaerobic organisms are guided by subsequent clinical progress and relevant culture results. Choices of antimicrobials include beta-lactam with beta-lactamase inhibitor and clindamycin. Beta-lactamase-producing organisms were reported in as many as 46% of head and neck abscesses in children.9,10 Hence, clindamycin is recommended in combination with a beta-lactam antibiotic for initial management while cultures are being processed. 1 If intravenous systemic antibiotics are started early (i.e. within the first 24 to 48 hours following the onset of pain when the infection is at the stage of cellulitis), the condition may be resolved by fibrosis without abscess formation. Frank pus generally forms on about the fifth day. If the patient is not seen until pus has developed, or if antibiotic therapy fails, the abscess must be drained surgically.7 History of peritonsillar abscess has been used as an indication of tonsillectomy because the recurrence rate for another peritonsillar abscess is reported to be as high as 25%.11,12 Those with a history of recurrent tonsillitis have a four times greater risk of recurrent peritonsillar abscess comparing to those without an antecedent history (40% vs. 9.6%).13 Therefore, tonsillectomy is recommended after peritonsillar abscess in any patient with a previous history of recurrent tonsillitis or in those patients at an increased risk of complication if an abscess recurs, e.g. diabetes mellitus, immunodeficiency.3 Complications of peritonsillar abscess are related to airway obstruction and aspiration of purulent material. Vascular complications usually are related to spread of infection into the adjacent parapharyngeal space, which include thrombosis of the internal jugular vein and false aneurysm formation with haemorrhage of the internal carotid artery. The latter complication has been reported in peritonsillar abscess.3,7 Septicaemia is one of the complications of parapharyngeal abscess and can occur rapidly. The infection can spread directly via the carotid sheath or involve the retropharyngeal space and mediastinum. Vascular complications, i.e. jugular venous thrombosis, septic necrosis of the internal carotid artery with false aneurysm formation and subsequent rupture, are the most serious complications.7 Conclusion The presentation of deep neck infections may be atypical or subtle in children. Vomiting and abdominal pain in a febrile child should raise the suspicion of a serious infection, including peritonsilar and parapharyngeal abscess as in the current case. The warning signs of deep neck infections are neck mass, high fever, cervical lymphadenopathy, poor oral intake and neck stiffness irrespective of age. Early contrast computer tomography would help clinch the diagnosis that affords corresponding management.

I M C Chan, MBBS (HK), MRCPCH

Resident D K Ng, MD, M Med Sc (HK) Consultant Paediatrician Department of Paediatrics, Kwong Wah Hospital. Correspondence to : Dr Daniel K Ng, Department of Paediatrics, Kwong Wah Hospital, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR.

References

|

|