|

September 2007, Volume 29, No. 9

|

Original Articles

|

Referrals from general practitioners to medical specialist outpatient clinics: effect of feedback and letter templatesKenny Kung 龔敬樂, Augustine Lam 林璨, Philip K T Li 李錦滔 HK Pract 2007;29:348-356 Summary

Objective: To determine whether providing feedback and educating

doctors about referral guidelines will help to improve the quality of referral letters

and referral rates.

Keywords: Referral, triage 摘要

目的: 調查給與轉介回覆和教導醫生轉介指引可否改善轉介信的質量和轉介率。

主要詞彙: 轉介,分流。 Introduction Referral implies a transfer of responsibility for some aspect of patient's care.1 Indeed, one of the principles of management in Family Medicine is appropriate referrals.2 In a world of unlimited resources, patient referrals should allow the immediate transfer of responsibility to the other party, allowing early management. However, common to all current health care systems, we are facing prioritization and inevitably long waiting time within secondary care level of public institution in Hong Kong. This "wait and delay" results in patient and medical staff dissatisfaction, while at the same time, increases adverse outcomes and health care costs, as well as reduces potential income.3 In a mixed medical economy, Hong Kong residents have learnt to "doctor-shop" to counterbalance the cost of waiting.4 Waiting time for the first appointment of consultation at specialist outpatient clinics (SOPC) operated by the Hospital Authority (HA) varies from one patient to another depending on the patient's clinical conditions and on the patient load of the clinic at the time. Particular factors that are considered include patient's clinical history, the presenting symptoms, findings from physical examination and investigations.5 All patients are then triaged into three categories: priority one (P1) for patient with the most urgent medical needs; priority two (P2) for those with comparatively less urgent medical needs; and routine for patients whose medical needs do not appear to be urgent. The median waiting time in HA for priority one and two cases are within two and eight weeks respectively.5 Structured triage guidelines from various specialties are available and periodically reviewed by specialists. The triage procedure is conducted by well-trained nurses and backed up by specialists. The referral letter is a key instrument in moving patients from primary to secondary care services.6 Efficiency of the referral process is therefore a function of the quality of referral letters, which have been shown to be of questionable standard in some overseas studies.7-9 Of particular importance in our locality is the lengthening of waiting time for new referrals. Referrals from general outpatient clinics (GOPCs) comprise at least 30% of medical SOPCs new case referrals. Prolonged waiting time is a direct consequence of an increased workload from excessive routine referrals. Reducing the number of these routine referrals, referring only those P1 and P2 cases, and reducing the total number of referrals should logically lighten the workload in medical SOPCs, hence reduce overall waiting time. This study aims to determine whether providing feedback and educating doctors about referral guidelines will help to improve the quality of referral letters and referral rates. Methods Study setting and collection of referral letters This study was conducted in Shatin District of the New Territories East Cluster of HA. Within this district, there are one medical SOPC located in the Prince of Wales Hospital and four GOPCs (Shatin Clinic, Yuen Chau Kok Clinic, Lek Yuen Clinic, Ma On Shan Family Medicine Centre). Hard copies of all referral letters sent from the above four designated GOPCs to medical SOPC between 1st October 2004 and 31st January 2005 were collected for the first round of data analysis. The second round of collection took place from 1st March 2005 to 31st June 2005. At this stage, doctors could produce either hand-written or computer-generated letters. Letters were collected both from individual GOPCs and from medical SOPC to ensure adequate coverage. Intervention: Feedback sessions and use of referral templates Data from the first round of data collection were presented to all GOPC doctors working in our study locality in two separate but identical sessions. These sessions were presented by the authors. Session objectives include:

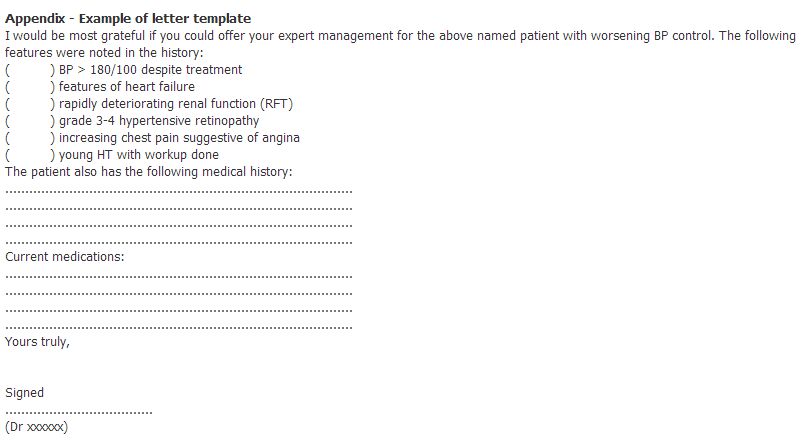

Since all GOPC doctors are using computer system during their consultations, referral letter templates containing triage criteria of medical specialist clinic were uploaded onto the NTEC GOPC computer management system for easy retrieval. Templates were made available for a comprehensive list of problems commonly requiring referral to medical SOPCs, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, headache, chest pain and cardiovascular disease, liver diseases, asthma, chronic obstructive airway disease, obstructive sleep apnoea, renal diseases, haematological diseases, thyroid diseases and rheumatological diseases. Criteria for each disease subgroup are listed out in point form, allowing doctors to select individual criteria if present. These templates serve to allow doctors to have easy access to triage guidelines, as well as facilitating the writing of referral letters to medical SOPCs (please see appendix for an example of the letter template). In addition, doctors were encouraged to provide computer-generated referral letters. Outcome measures The main outcome measures were the number of components included in referral letters and the rate of non-routine referrals. Components included in the HA standard referral letter10 were taken as the standard components that should be included. These comprise the following:

Reference guidelines for use by doctors working in NTEC with regard to medical specialist referrals have been set up by medical colleagues within NTEC. These guidelines are used by medical triage personnel to categorise patients into 3 major categories as stated in the introduction. For the purpose of this study, only two categories were considered: early and routine. Early cases are equivalent to P1 and P2 patients, whose first appointments are within eight weeks. Routine cases are those non-priority cases whose first appointments are beyond eight weeks. Each referral letter was also checked to see the number of letters fitting the recommended P1/P2 criteria. The training background of referring GOPC doctors (trainees and fellows in Family Medicine, other specialists with fellowship qualifications and non-fellow/non-trainees) and the percentage usage of letter templates were also included as part of our data collection. Data analysis The number of referral letters collected was matched with the monthly medical referral statistics obtained from each GOPC. The percentage of P1/P2 appointments and the quantity of referral letters before and after intervention were calculated, from which the relative reduction in non-routine appointments was extrapolated. Likelihood ratios with 95% confidence intervals were obtained to see whether letters fitting recommended triage criteria translated to a P1/P2 appointment booking. Results Reduction in overall referral rate In total there were 618 and 423 GOPC referrals to medical SOPCs in the period 1st October 2004 to 31st January 2005 and 1st March 2005 to 31st June 2005 respectively. During this period no significant changes in manpower or clinic workload was observed. The overall referral rate dropped from 0.49% per consultation to 0.34% (P<0.05). Referral templates were used in only seven letters, with six resulting in early appointments. Differences in improvement in different doctor subgroups Table 1 showed the number of referrals that resulted in appointments within eight weeks of the letter date, stratified according to doctor training. In all doctor subgroups there was an increase in the percentage of early appointments after intervention, although only the results in the non-fellow/non-trainee and FM (Family Medicine) trainee subgroups were statistically significant. These results were also graphically presented in Figure 1. There were no significant differences in the percentage of early appointments between different doctor subgroups at both stages. Lack of influence of the number of components included in letters The distribution of the number of standard components included in referral letters was shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences in the number of components included in letters before and after intervention. No significant correlation was found between the number of components included and the likelihood of receiving P1/P2 appointments. Criteria fitting and relationship with appointment time Relationships between the likelihood of receiving P1/P2 appointments and letter contents fitting P1/P2 triage criteria were illustrated in Table 3. Despite fitting P1/P2 criteria, referral letters for neurological disorders (before intervention) and respiratory disorders (after intervention) did not result in a significant increase in the number of P1/P2 appointments. Significant increase in criteria fitting after intervention were noted in referrals for blood pressure problems, cardiac related disorders, gastrointestinal disorders and thyroid disorders (Figure 2). Discussion In this study, the provision of feedback and reminder sessions to doctors resulted in significant increases in the rate of early appointment booking. Results in the "other specialist" and "FM fellow" subgroups did not reach statistical significance, but this is likely to be a result of their relatively small numbers in GOPCs. Overseas reports have also shown similar positive response after peer review and feedback.11,12 One major factor in this improvement is the inclusion of P1/P2 criteria in letters, allowing prompt and accurate patient triaging at medical SOPCs. It is possible that in the past some doctors used letters to obtain referrals without feeling a need to provide detailed clinical history. Presumably reminder sessions help to reinforce doctors about the important "red flags", promoting triaging at the GOPC doctor level as well as educating GOPC doctors to recognize those salient features that are deemed important by medical specialists. Writing referrals is different from taking a history. A typical history must be detailed enough to rule in or rule out essential differential diagnoses. A referral letter, however, needs to contain only those essential features that help the specialist in differentiating the patient's severity. A letter that contains standard components without due regard to those essential features will not in any way facilitate management. Indeed, this may unnecessarily prolong patient's waiting time, potentially withholding proper care. Improvement in communication between primary care physicians and specialists is possible with the use of templates,13 and it was hoped that its use for common diseases would serve such purpose. Despite its easy access in the computer and its user friendliness, templates were used in less than 2% of occasions in our study, although its efficacy in obtaining earlier referrals was high (86%). It is unclear why the usage rate was so low, but differences in writing styles, unfamiliarity with template usage in the computer system, and subjective relevance of the template to the actual clinical scenario are possible reasons. The provision of guidelines on specialist outpatient triage system is not without flaws. As can be seen in this study, letter contents that included P1/P2 criteria might not result in an earlier appointment for patients. Such guidelines are set not only with respect to clinical needs, but also in relation to health economical considerations. The time lapse between the establishment of triage criteria, its implementation in SOPCs and then its subsequent distribution to GOPCs is a major contributing factor for the mismatch in appointment booking. At the moment the channel of communication between GOPCs and SOPCs is inefficient. Further improvement in quality of referral can only occur if this issue is addressed. It is encouraging to note that letters from doctors with sufficient training in FM were more likely to result in earlier appointments for patients before and after intervention, although both results did not reach statistical significance. The lack of significance mainly stems from the relatively small numbers of FM fellows working in GOPCs and the associated small percentage of letters written. Anyhow, it can be anticipated that larger numbers of qualified family physicians could translate into a more effective primary care environment in GOPCs, at least in terms of improving referral rates to medical SOPCs. A proficient gate-keeper in the referral system needs to take into account the three perspectives on urgency before referrals: the patient sense of urgency, the SOPC doctor's sense of urgency, and his/her own urgency in the problem. It is therefore not surprising that FM fellows had better referral rates, since their training demands skills in communication between patients and professionals. Improvement in quality of referrals should include a reduction in the total number of referrals. Although there was an overall decrease of specialist referral after intervention, it might be due to seasonal variation only. Ongoing data collection would be necessary to eliminate that possible bias. The long term impact of a single feedback session on doctors is uncertain. Indeed, such sessions would be necessary if GOPC manpower constantly reshuffles. Limitations This study has only looked into referrals within the Shatin region. Further analysis involving GOPCs and SOPCs in other regions will allow data to be more representative of the overall situation in Hong Kong. Conclusion Providing feedback and information on referral guidelines to doctors in GOPCs help to increase the quality of referral letters in terms of rate of receiving early appointments. In addition, a small reduction in the overall referral rate was seen. In view of manpower changes and the lack of long term data on the effect of a single feedback session, regular sessions would be very useful to update GOPC doctors' knowledge on SOPC triage systems.

Key messages

Kenny Kung, MRCGP, FRACGP

Resident, Augustine Lam, FHKAM (Fam Med), FRACGP Consultant, Family Medicine, Prince of Wales Hospital. Philip KT Li, MD, FHKAM (Medicine) Professor of Medicine, Family Medicine Training Centre, Prince of Wales Hospital. Correspondence to : Dr Kenny Kung, FMTC, 3/F South Wing, LKSSC, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, NT, Hong Kong.

References

|

|