|

September 2007, Volume 29, No. 9

|

Original Articles

|

An evaluation on the efficacy of "General Exercise for the Elders" on endurance, strength, balance, flexibility and quality of lifeEva Siu 邵伊華, Tung-yue Li 李統宇, Chiu-kwan Lau 劉昭君, Margaret W F Lam 林華鳳, Kin-shing Lam 林建成, Shi-wai Fung 馮仕為, King-bun Chan 陳景濱 HK Pract 2007;29:334-347 Summary

Objective: The study is aimed at evaluating the efficacy of the

'General Exercise for the Elders' (GEFE) programme on aerobic endurance, strength,

balance, flexibility and quality of life.

Keywords: Elderly, Exercise, Ageing 摘要

目的: 本研究旨在評估「活力長者健康操」(GEFE) 對改善帶氧忍耐力,肌力,平衡力,柔韌度和生活素質的成效。

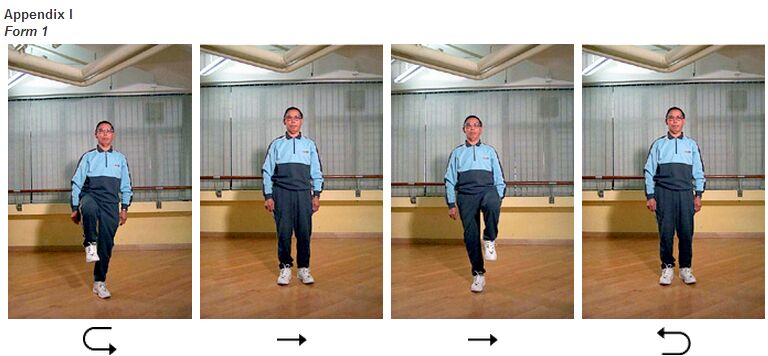

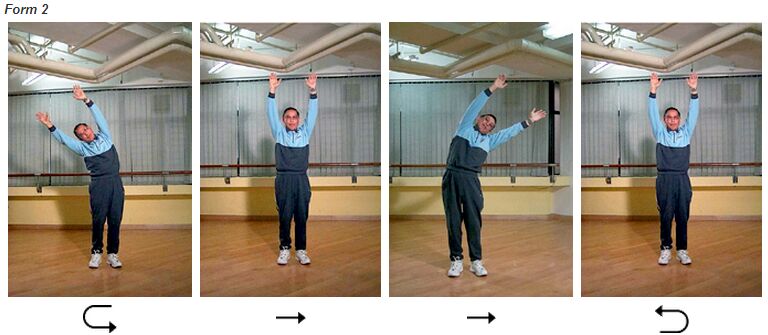

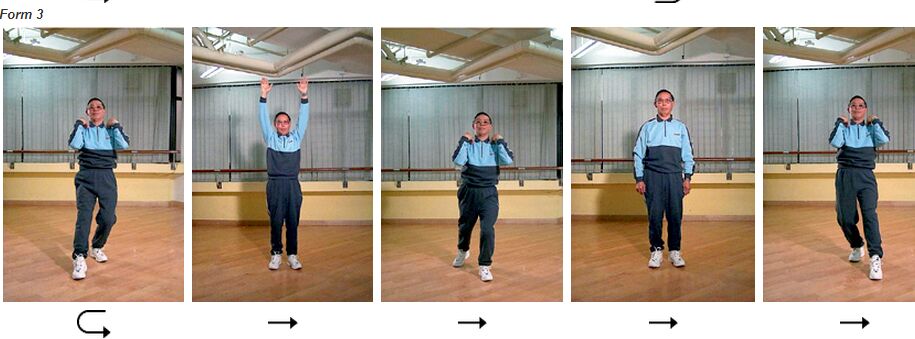

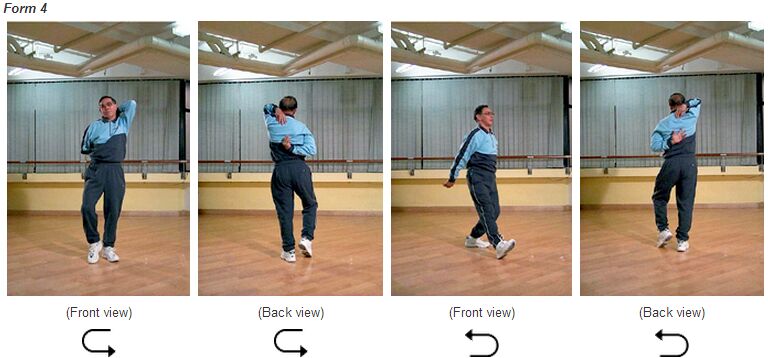

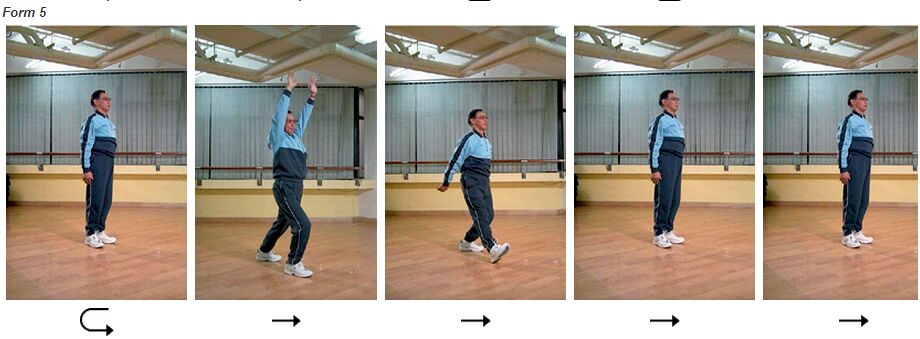

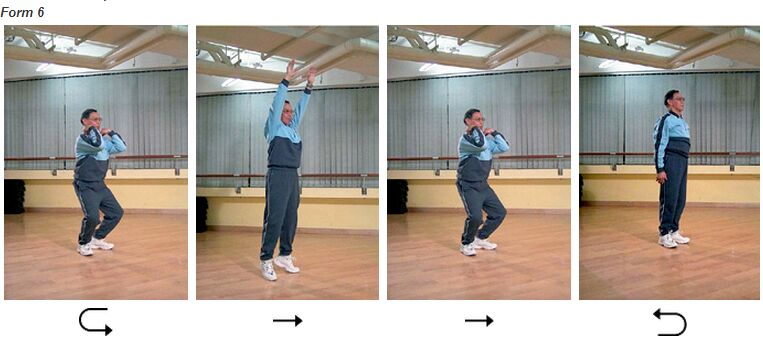

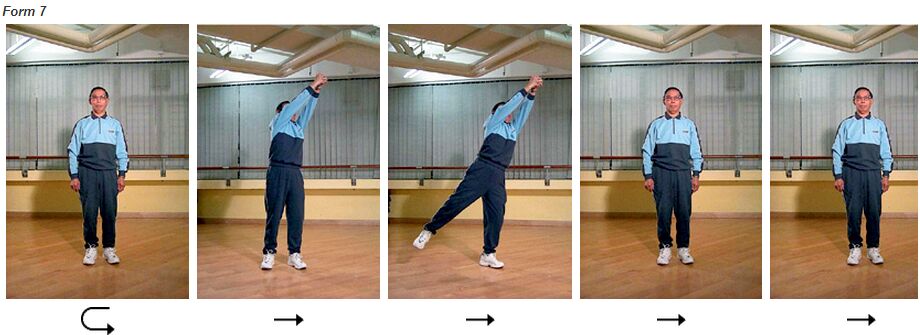

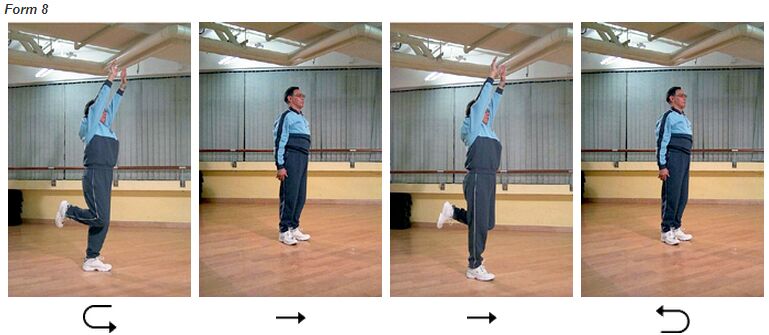

主要詞彙: 長者,運動,老化。 Introduction Background In Hong Kong, like elsewhere in the world, there is a rapidly growing elderly population. This can be due to socioeconomic development and better medical services resulting in a longer average lifespan. As people are now living longer, health-promoting lifestyles are essential in order to maximize the quality of life in the latter years. Among the components of healthy lifestyle, exercise is one of the most important. Physical inactivity has been demonstrated to increase the risk of chronic disease, for example, coronary heart disease (CHD), hypertension and non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus.1,2 Other consequences of physical inactivity include a decrease in cardiovascular fitness and musculoskeletal function; for example: strength, flexibility and balance, with the end result being a decrease in the quality of life, physical function and mobility. In the ageing process, there is a decline in functional capacity including aerobic endurance, muscular strength, balance and flexibility. Cardiac output and vital capacity are lowered in the elderly and with this their aerobic endurance.3 Muscle mass reduction during ageing leads to muscular strength decline.4 The decline in muscular strength together with decrease in reaction time and flexibility contributes to the decrease in balance and the increased likelihood of falls. However the rate of decline depends on factors related to active lifestyle such as level of physical activity and exercise habit. The basis for healthy ageing involves the promotion of a healthy lifestyle, with methods for reducing health risks and increasing the quality of life for that individual.5 In order to achieve healthy ageing, active ageing is a pre-requisite in health promotion. Regular exercise and physical activity contribute to a healthier, independent lifestyle and greatly improved quality of life in ageing population.4,5 Participation in regular physical activities elicits a number of favourable responses that is known to contribute to healthy ageing. Apart from the maintenance and improvement of the cardiovascular function, regular exercise can also reduce risk factors associated with heart disease, diabetes mellitus etc as well as leading to an improvement in health status.4,5 Studies have shown that strength, functional motor performance and balance can be significantly increased in a group of geriatric patients with a history of injurious falls after 8 to 12 weeks training.6,7 Fall-related behavioural and emotional restrictions were also reduced significantly and sustained during the 3-month follow-up.6 Other studies are also available which have shown effectiveness of exercise programmes on the functional performance of elderly populations. Rubenstein et al8 showed 10.4% improvement in the aerobic endurance of the exercise group. With better aerobic endurance, the elderly will find themselves more energetic. In the study of Richardson and his colleagues,9 a significant improvement in balance in the intervention group was shown. Lazowski et al10 and Shin11 showed a significant improvement in the flexibility of the exercise group. With improvement in balance and flexibility, fall incidents may be prevented. All these studies have shown that the physiological, physical and psychological changes due to normal ageing can be minimized by exercise. Other benefits of physical activity include an enhancement in the perceived quality of life.12 Quality of life is a broad concept integrated with an individual's physical health, psychological status, independence level, beliefs and relationship to environment factors.13 The improvement on the physical health with exercise can enhance their independence and self confidence on daily functional performance. In addition, exercise can improve mood. Hence psychological health can be improved. And in turn the quality of life will be improved. Most old people perform some form of physical activity and exercise. The most common type of self reported exercise among Elderly Health Centre enrollees is general mobilization which is a non-specific and non-structured form of exercise. In view of the benefits of exercise in advocating healthy ageing, a structured and organized form of exercise programme - General Exercise for the Elders (GEFE) was designed. The GEFE was designed to improve aerobic endurance, strength, balance and flexibility and hence, quality of life. GEFE consists of a set of exercises with nine forms which are performed in a repeated and cyclical manner. The design of GEFE is based on the musculoskeletal system and body mechanics. GEFE involves using different muscles which in turn are involved in the control of certain bodily movements. Major joints and muscles groups are involved. Some of these forms are similar to, but a simplified pattern of, traditional exercises like Tai Chi Chuan which have been shown to improve cardiovascular function, strength and balance.14,15 GEFE is simpler and easier for the elderly. Together with the clinical experiences in exercise prescription for elderly, GEFE is a newly designed and tailored made new content of exercises which was developed to meet the needs of the unaided ambulatory elderly. There are only nine forms and each form has a Chinese name which describes the movement and makes it easier to remember. All forms of GEFE are performed in the standing position. The exercise can be practised as an indoor or outdoor activity. The Elderly can perform the exercise in a group or alone without using sophisticated exercise equipment. All these factors make GEFE practical for elders. The starting position is always standing with feet shoulder width apart. The first form is high stepping of lower limbs with swinging of upper limbs. The second form consists of both hands reaching up with trunk alternate side bending. The third form consists of both hands touching shoulders and then reaching up, at the same time alternate foot pointing forward and then pointing backward. The fourth form is alternate touching of hands one from above and one from below at the back of trunk, at the same time, tipping of the alternate foot. The fifth form is alternate launching forward with upper limbs swinging forward and launching backward together with the upper limbs swinging backward. The sixth form is with both hands touching shoulders in a mini squat position, and then both hands reaching up and tip toeing. The seventh form is hands clasped and reaching up, then turn trunk to left side together with raising right lower limb sideway, repeated with the other side. The eighth form is with both hands reaching up with one knee bend, then return to starting position and repeat with the other knee. The ninth form consists of a ball game. Each form is done in a continuous pattern with a count of four or eight and repeated eight times before proceeding to the next form. These nine forms are then repeated for three times. [See Appendix I]

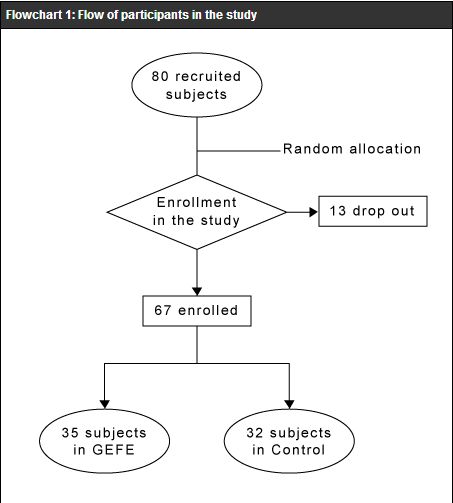

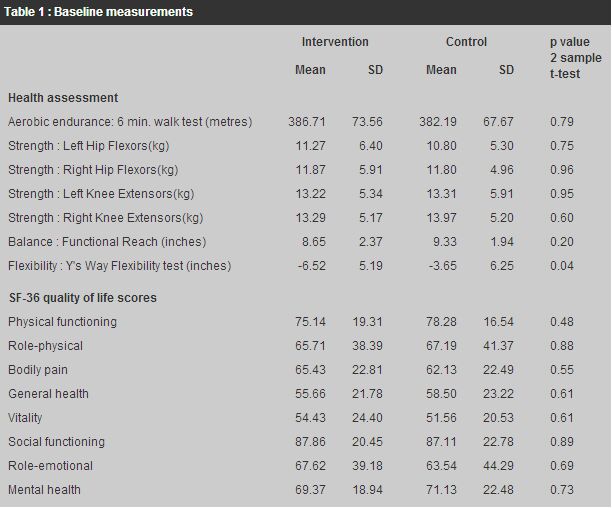

Objective This study is aimed at evaluating the efficacy of the newly designed General Exercise for the Elders (GEFE) on the primary outcomes of aerobic endurance and strength and other outcomes of balance, flexibility and quality of life. Methods Study design This was a 12-week clinical trial in which subjects were randomly assigned to receive GEFE Programme or a controlled activity. In an overseas study, the time needed for physical changes including strength and aerobic endurance has shown to have taken place in 12 weeks' time.7 Approval to conduct the research study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Department of Health, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Study population In Hong Kong, comprehensive primary health care services are provided by the Elderly Health Centres (EHCs), Department of Health. Elderlies aged 65 or above can be enrolled as members of EHCs, by paying an enrolment fee of HK$110, with waiving mechanism for those on public assistance. In order to address the multiple health needs of the elderly, members are provided with services of physical check up and health assessment, counselling and health education, and curative treatment. There are in total 18 EHCs in Hong Kong. Among the 18 EHCs, Kwun Tong EHC and Shek Wu Hui EHC were selected as recruitment centres for this study. Inclusion criteria Both new and re-enrolled, unaided ambulatory members of the selected Elderly Health Centres with health assessment done were eligible. To ensure the suitability of members' health status to participate in this study, only elders with health assessment done during the recruitment period were included. Re-enrolled members refer to old members with renewal of membership. Exclusion criteria Exclusion criteria were severe cardiac and pulmonary disease or vestibular disorder; uncontrolled hypertension or epilepsy; recent fracture (within past 4 months); total blindness or deafness; unable to follow instruction or demonstrations; severe joint pain and deformities; dementia; medically unresponsive depression or progressive neurological disease (e.g. Parkinson's disease). Subjects According to the above criteria, the corresponding medical officer of Kwun Tong EHC and Shek Wu Hui EHC recruited suitable candidates from the two centres after reviewing health assessment result. Each participant was assured of confidentiality and the right to decline or withdraw from the study at any time. Written consent was obtained and explanation was given to the participant at the time they agreed to join the study. Intervention A training of the GEFE programme for the intervention group was arranged. Components of the GEFE programme included: (i) general warm up and stretching; (ii) balance, coordination, flexibility and strength training and ball games (i.e. the nine forms of exercise); (iii) cool down and stretching. Another programme of general exercise and games for the control group was arranged. The contents of the programme included: (i) health education; (ii) word/memory games; (iii) range of motion exercise in sitting position (upper limbs, lower limbs, neck and trunk); (iv) relaxation exercise. Both the GEFE and control groups were conducted at each EHC for 30 minutes. The GEFE programme was conducted three times per week while the control group was conducted once a week over the three months evaluation period. Therefore, there were altogether 36 sessions and 12 sessions for the GEFE and the control group programme respectively. The control group programme has no specific effect on the physical changes because the general exercise is the usual practice of EHC members which is non-structured exercise programme. The control group is a sham / placebo group. Two experienced health promoters assisted in leading the groups. Physiotherapists provided the briefing and training sessions on the standard procedures of leading the groups to the health promoters. Throughout the study, physiotherapists played the role in continuous monitoring the whole process with advice given to both health promoters and subjects. At the end of the study, physiotherapists provided a brief consultation to each subject in both groups. Based on the result of the individual's condition, advice on reinforcing exercise habits and healthy lifestyles were provided. Outcome measures The main outcome measures were collected by five physiotherapists blinded to the subject allocation, were not involved in the exercise training programme. The procedure of taking data was standardized and the data was recorded in a standard recording form. Measurements were performed before randomization and at the end of the training period. Baseline measurements included measures of aerobic endurance,strength, balance, flexibility and quality of life as well as the average time spent on exercise activities. There were also intermediate assessments performed every three weeks of training for both the GEFE and control groups. Recordings included outcome measures of aerobic endurance using 6 minutes walk test,16 lower limb strength using the Nicholas manual muscle tester (MMT),17 balance using Functional Reach,18-20 flexibility using the Y's way test,21 and quality of life using the SF-36 questionnaire.22 Process measures including recruitment situation, attendance rate level, performance level, any cancellation of session due to unforeseen events, feedback on GEFE and unpredicted responses while performing the GEFE were also recorded in standard recording form. Statistical analysis Analysis was on an intention to treat basis, defined as all randomized subjects who had at least one baseline value and participated in at least one exercise class. For participants who withdrew we carried forward the last result of assessment. The planned sample size should be about 40 in each group, based on previous Lord et al's study,7 with a 30% expected withdrawal rate and to detect a difference of 4.6kg with an estimated standard deviation of 2.2 kg on the strength measurement with a=0.05 and b=0.20. For comparison of outcome measures between groups, we compared the final measurements in the two groups using analysis of covariance with adjustment for baseline measurements. All the analyses were conducted with the use of SPSS software (version 10.0).23 Results Subjects There were altogether 80 recruited subjects. Randomization was provided in blocks of four clustered by centre. A computer generated list of random set numbers was generated by an independent officer. 67 subjects were enrolled into this study. 13 subjects never turned up in the training programme. The reasons included lack of time (n=5), lack of interest (n=2), admitted to hospital (n=1), acute onset of back pain (n=1) and upper limb joint pain (n=1), away from Hong Kong (n=2) and newly diagnosis of dementia (n=1). The GEFE group included 35 subjects (males=17; females=18). The control group included 32 subjects (males=12; females=20). The drop out rate for the GEFE group and the control group were 12.5% and 20% respectively. [see Flowchart 1] The age of the enrolled subjects ranged from 66 to 88 years old. The mean age was 72.8 years old (standard deviation = 4.30 years) for the GEFE group and 72.0 years old (standard deviation = 4.55 years) for the control group. Baseline measurements of outcomes for GEFE and control groups were shown in Table 1. There were no differences in the aerobic endurance, lower limb strength, balance and quality of life status. Only the flexibility data showed baseline difference between the GEFE and the control groups. [see Table 1]

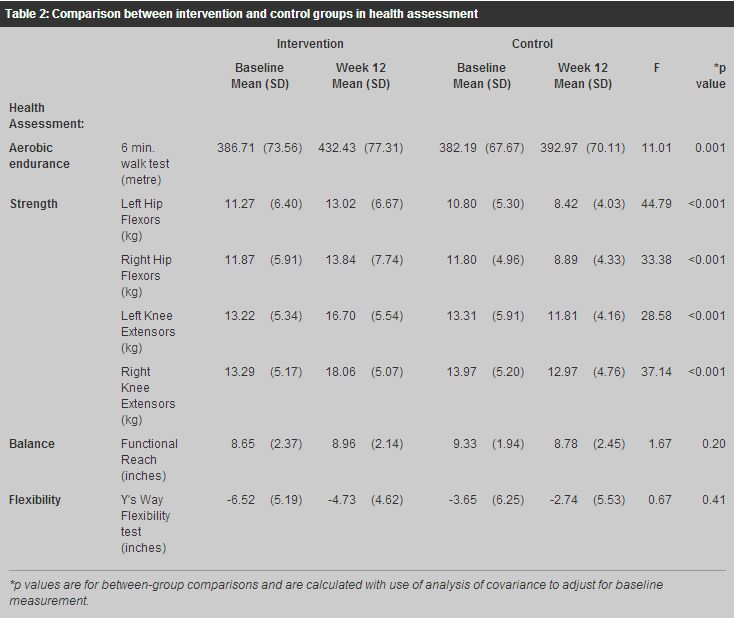

Outcome measures Process measures The recruitment procedure was smooth and all 80 subjects were recruited in about two months' time. No injurious or accidental events happened during the exercise sessions. Neither was there any cancellation of session due to unforeseen events happening. There were altogether 36 sessions for the GEFE group with an average attendance rate of 74.9% (approximately 27 sessions). There were altogether 12 sessions for the control group with an average attendance rate of 65.4% (approximately 8 sessions). The reasons for absence were sickness, unavailability, forgetfulness, scheduled medical follow up appointments and requested leave for personal engagement. During the study period, one subject experienced upper limb pain with diagnosis of frozen shoulder and another subject experienced difficulty on doing the fifth form because of calf tightness due to a previous operation. The in-charge physiotherapists was responsible for the provision of precaution, guidance as well as monitoring their progress regularly. This did not affect the schedule and participation of subjects. There were nine forms of exercise in the GEFE. At the beginning of the GEFE class, some subjects could not pick up all forms at one time because they were not familiar with them. However, after 3 sessions, all forms of exercise were picked up without any problems. The GEFE group subjects reported and shared their experiences with each other. They reported improvements in balance, strength, gait stability and speed; reduction in back pain, knee joint stiffness and cramps; improvement in bowel habits; and improvement in quality of sleep and general condition. Some subjects were even motivated to establish a regular exercise habit by the GEFE intervention or requested the establishment of GEFE exercise routine in EHC. Health assessment After twelve weeks of training, the GEFE group showed statistically significant improvement in aerobic endurance and strength with p-values 0.001 and <0.001 respectively. In the other outcome measures on balance and flexibility, the changes did not have statistical significant result between groups. [see Table 2]

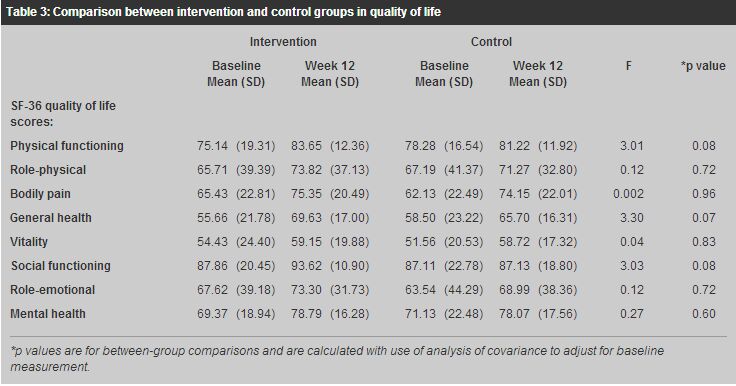

Quality of life SF-36 Questionnaire was the outcome measure for quality of life. There were altogether eight domains measurement including physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional and mental health. In order to control type I error for the multiple comparison in this outcome measure, the p-level for significance was lowered to 0.006 using Bonferroni procedure. There were no statistical significant differences revealed between groups for all the SF-36 domains. [see Table 3]

Discussion Outcome measures Health assessment

The GEFE is designed to encompass several health benefits. The major purpose of GEFE is for the improvement of aerobic fitness. According to Mazzeo and colleagues,3 there is an age-related deterioration in cardiovascular function. It was reported that a 5% to 15% decrease of maximal cardiovascular function every ten years after the age of twenty-five. The 6-minute walk test was related to exercise capacity and endurance in the elderly.24 In Harada study,25 6-minute walk test was found to be a tool for measuring mobility-related function in the elderly. In our study, the 6-minute walk test was significantly improved between groups. Hence practising GEFE may slow down age-related decline in cardiovascular function and may improve daily functional activities that require certain level of aerobic fitness.

Because ageing was shown to decrease muscle strength by 30% between the ages of 50 and 70 years. This decline increased even more after the age of 70 years.3 Muscles strengthening become an indispensable component of any exercise programme for the elderly. The different forms of exercise in GEFE involved the work of lower limb muscles using body weight as resistance. The remarkable improvement shown in muscle strength after practicing GEFE suggests that GEFE is an effective exercise programme to combat the normal decline in muscle strength due to inactivity or normal ageing. Strength was also found to be associated with physical function like walking speed in the elderly.26 With the increase in strength by exercise like GEFE, the physical functions of the elderly can be improved or maintained.

The GEFE was performed in a standing position. Some forms of GEFE required co-ordination of limbs, weight shifting in alternate lower limbs and standing on single leg. These forms of GEFE challenged the balance of the GEFE group. Though the result did not reach statistical significance between groups, there was still improvement on balance outcome in the GEFE group. Duncan and colleagues18 reported that the normal values on functional reach for elderly in the Western country ranged from 1.6 inches to 19.3 inches. The mean values on functional reach for the GEFE and the control groups were 8.65 inches and 9.33 inches respectively. The overall mean value for the subjects was 8.99 inches which is in the normal range for elderly in the Western country. Therefore the balance of the subject is within the normal range at baseline. This may be the reason for the statistical insignificant result.

The baseline result of the subjects on flexibility was poor. The value of this measurement was supposed to be a positive value. In the flexibility test, it was observed that most of the subjects could not reach the zero mark and therefore the measurements were recorded with a negative value. With this finding and observation, the elderly in this study may need more intensive flexibility training to get a better effect on improving flexibility.

The outcome of exercise on quality of life may need a longer time to take effect. Hence, it is not surprising that there was no statistically significant difference on the quality of life scores between the two groups. SF-36 quality of life outcome measure domains all improved in the GEFE group. This showed that GEFE intervention may have the potential to improve quality of life in the long run.

The physiotherapist trainers reported that subjects enjoyed the game in the ninth form of exercise. In this form of exercise, the subjects' dynamic balance was challenged with the demand on hand-eye coordination and balance reaction. Importance on subjects' exercise session adherence to outcome was found in other study.8 Hence reminder phone calls were made to subjects in both groups before each session. In our study, most of the subjects partially attended the exercise sessions. In the GEFE group, 30 out of 35 subjects (i.e. 86%) attended 50% or more of the total number of sessions (i.e. 36 sessions). In the control group, 22 subjects out of 32 subjects (i.e. 69%) attended 50% or more of the total number of sessions (i.e. 12 sessions). Limitations / recommendations It is well documented that the regular practice of exercise has a beneficial effect on health and fitness.27 However, it is difficult to totally exclude those subjects with an exercise habit. From the 2000 statistical record of health assessment of all EHCs,28 more than half of the EHC members (64.7%) were found to have a regular exercise regime. Subjects in the GEFE group reported that they also practised GEFE at home during the study period. This detailed information was not recorded in our study. Documentation on the time spent on this extra practice would provide useful information for further analysis. The exercise dosage of subjects in the GEFE group were more than planned which would have led to an exaggerated effect of the GEFE. The control group met once a week as compared with three times a week for the GEFE group. This may introduce drawback due to dosage difference between the GEFE and the control groups. However the general exercise practice in the control group was the usual practice of EHC members and the effect of this general exercise practice is expected to be minimal. Furthermore, there were more than one physiotherapists involved in the assessment of the subjects. Inter-rater bias may be introduced. The bias was minimized by the provision of a briefing session before the commencement of the study to standardize the assessment methods. The input provided by physiotherapists may limit generalization and application of results to other community elders. In order to improve the GEFE intervention on the balance and flexibility outcome measures, physiotherapists can conduct individual assessment of impairment in balance and flexibility for exercise programme planning. Possible reason on the noted insignificant results may be because the study period was not long enough. Further studies of longer duration are recommended as well as the assessment of change in body weight and other co-morbid factors. Finally, a self-learning home exercise programme can also be considered. Conclusion The effect of training depends on exercise frequency, intensity, duration and level of fitness of an individual. With the twelve weeks GEFE training, our EHC members showed an improvement in their strength and aerobic endurance. Practising exercise in a group format not only fosters a regular exercise habit in the elderly, but the psychosocial needs of the elderly were also met by providing social interaction and peer support. In many studies, strength training usually requires extra equipments.7,8,29 On the other hand, performing GEFE does not require any equipment. Hence, GEFE is convenient and practical for the elderly. GEFE is an exercise option for the elderly population to start with. Acknowledgements Grateful thanks are extended to Dr WM Chan, JP, Dr Ho Kin Sang, Dr Teresa Li and Dr Kellie So for the continuous advice and Mr Raymond Li and Miss Shelley Chan, Research officers for help in research analysis in the Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR. The advice from Dr KC Tang in the World Health Organization is gratefully acknowledged. Key messages

Eva Siu, Master in Primary Health Care, Professional Diploma in Physiotherapy

Physiotherapist, Tung-yue Li, Master of Health Education and Health Promotion, Postgraduate Diploma in Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Professional Diploma in Physiotherapy Physiotherapist, Chiu-kwan Lau, Master of Health Management, Professional Diploma in Physiotherapy Physiotherapist, Margaret W F Lam, Professional Diploma in Physiotherapy Physiotherapist, Kin-shing Lam, Professional Diploma in Physiotherapy Physiotherapist, Shi-wai Fung, Master of Science in Health Care (Physiotherapy), Professional Diploma in Physiotherapy Physiotherapist, King-bun Chan, Master of Applied Science (Physiotherapy), Bachelor of Science in Physiotherapy Physiotherapist, Elderly Health Service, Department of Health. Correspondence to : Ms Eva Siu, Elderly Health Service, Department of Health, 2/F, 28 Tai Hong Street, Sai Wan Ho, Hong Kong.

References

|

|