|

March 2007, Volume 29, No. 3

|

Update Articles

|

The family physician's role in cancer prevention*Cynthia S Y Chan 陳兆儀 HK Pract 2007;29:92-100 Summary This paper discusses the role of the family physician in health promotion, screening, preventive advice and early diagnosis of a few common cancers in Hong Kong, both from personal experience and by review of evidence-based guidelines. Strategies for implementation in busy general practice are briefly described. 摘要 本文討論家庭醫生在健康推廣,普查,保健咨詢和某些常見癌症的早期診斷方面所擔當的角色, 包括作者個人經驗與及實證醫學指引的回顧,並概述如何在繁忙的全科診所實施的策略。

*Modified from a paper presented in the 13th Hong Kong International Cancer

Congress on November 17, 2006.

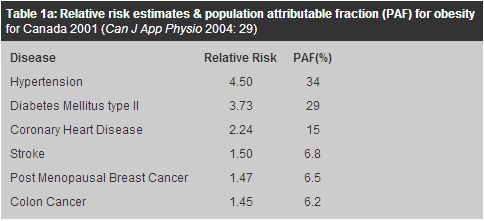

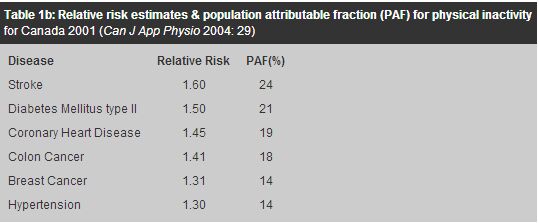

Introduction I was given the task to speak on this topic at a recent Cancer Congress. I asked myself what expertise a family doctor could offer on this specialized subject. Initially I could only think of prevention. However as I looked back, I indeed have had the privilege of caring for a number of cancer patients. During my recent visit to Vancouver, I had the opportunity to observe how end of life care is provided by family doctors and community nurses in patients' homes. The British Columbia (BC) Cancer Agency has a rich source of information. Hence, in addition to reviewing the local Hong Kong statistics on cancer incidence, and the evidence based recommendations for screening and prevention of some of the common cancers, I have come to a newer insight about the role of the family doctor in cancer care. I. Reflections on my own experience and the role of the family physician in cancer care If only it could have been detected.....earlier My father died of cancer before he reached 40. He had a non-painful neck lump for which he failed to seek medical care till six months later, because he was asymptomatic and busy with other duties in his life. Earlier presentation to the doctor might have made a difference. Health knowledge is required to facilitate secondary prevention. A friend was grateful that her breast cancer was discovered "early". She had been too busy doing volunteer work to go for the free mammogram screening offered to Canadian women, after her last one 7 years earlier. She noticed a lump recently and just had it excised. "My mother and sister both died of breast cancer at age 50. I am luckier as I am now 65," she said. With her family history, her doctor had a duty to remind her to go for the screening on a regular basis. Making the diagnosis Early in my career, I substituted for a doctor friend who was sick. It was a late Friday afternoon. The last patient at the end of the day was A, a 19 year old brought by his mother for haemorrhoids. The level of parental anxiety seemed out of proportion to the complaint. Anyway, as a dutiful doctor, I asked him to lie down for an abdominal examination before I checked his anus. To my horror, his body was covered with a diffuse petechial rash. It only took a simple blood picture to confirm the diagnosis of acute leukaemia. All I needed to do was to examine the patient and not trivialize his complaint. B, a lady in her sixties fainted one afternoon several days after the death of her husband C. Although she had a history of angina and hyperlipidaemia, in addition to the logical differential diagnoses of cardiac event, exhaustion from prolonged care of an ill husband and recent bereavement, she turned out to have endometrial cancer. If one listens to the cue, she gave a history of regaining consciousness to find blood on her underpants. Post menopausal bleeding in a middle aged obese woman is a red flag for endometrial cancer. D was an 80 year old new patient who came for a check up. A pap smear was offered as she has not had one for many years. Cancer of the cervix was diagnosed and treated. Abiding by screening guidelines, using a little persuasion and a gentle approach with a small speculum were all that was needed for the diagnosis and a grateful patient. E was a 70 year old diabetic who was noted to have a breast lump on routine breast examination. She refused surgery and took Tamoxifen for years before she passed away. Another 80 year old hypertensive with stroke and chronic obstructive airway disease came for regular follow up. As I examined her chest, asymmetry of her breasts was noted. Cancer of breast was later diagnosed, but she survived her cancer. Again, one only has to keep one's eyes open and observe the patient to make the diagnosis. Diagnostic challenges A 50 year old man brought by the wife for marital counselling, in passing, mentioned easy tiredness. His mild anaemia turned out to be caecal cancer. Fortunately he is still doing well 5 years after his operation. 80 year old F had gross haematuria. IVP and cystoscopy were negative. Yet the haematuria persisted. Repeat cystoscopy finally identified bladder cancer. Investigations may show false negative results and it is wise to repeat them if the patient's symptom persists. Happy surprises A patient told me the story of her husband. He was labelled as incurable "lung cancer" but turned out to have curable tuberculosis. 45 year old, G, had multiple somatic complaints before; but she took her breast cancer diagnosis remarkably well, - perhaps glad that she finally, by having a serious disease afterall, proved the doctors were wrong. She went on to recover from another cancer of the opposite breast and later cancer of one ovary. Now she is as optimistic as ever; very different from another patient who had successful breast cancer surgery but died of depression, having never recovered from the shock of hearing her cancer. G's daughter of course will need to be counselled about her risk of cancer and genetic screening. Difficult decisions 75 year old, H, had lung cancer and was unfit for operation. She decided not to try chemotherapy. She was well enough to go back to her village to choose a burial site. She became a Christian and passed away knowing she was going to be with her Lord, Jesus Christ. Her family supported her decisions throughout her last journey. While I could accept the 70 year old E's decision to refuse surgery for breast cancer, it was to my dismay that a 35 year old health professional refused even a lumpectomy. I searched the internet together with her, trying to convince her with scientific evidence about the importance of surgery. She died a year later, still holding a grudge that her dysfunctional family was the cause of her cancer. Walking the last lap I had walked the last journey with C and his wife, B. He too had lung cancer. She has adjusted to widowhood and the hysterectomy. Now she is enjoying life, confident that she has done a good job nursing her husband, and glad that she herself has recovered from cancer. Sad outcomes The 19 year old leukaemic, A, passed away. It was with regret that I did not visit a 37 year old male with nasopharyngeal cancer during his last admission. A 75 year old lady passed away with colon cancer. Her worst fear was the disintegration of her family. Her prophecy was correct. Even though her children continued to see me after her death, they stopped contact with one another. Their long-suffering mother was the only glue that kept the family together. As I reflected on these patients and their life stories, I realized that as family doctors, we do have important roles to play in cancer prevention, diagnosis and management. Although we are not the major partner in cancer treatment, it is important that we keep up to date with health promotion, early diagnosis (secondary prevention) and screening of cancer. Even after referring the patient to treatment by specialist oncology teams, we have a continuing role in providing tertiary prevention, ongoing explanation and support to the individual and their family, and walking the last lap and beyond. Our role does not end with the patient's death, as their family members may still need our care and continue to be our patients. As cancer diagnosis and treatment improve, more patients will recover from their cancers and may then go on to develop other serious diseases. They should be cared for like patients with chronic diseases. We have to be watchful not only for cancer recurrence, but also for risk factors for other causes of death and morbidity, including anxiety and depression. II. What can the family doctor do for cancer prevention? 5 Give You 50 "Do you know that 50% of cancers are preventable? And that there are 5 primary preventable risk factors?" That is the message of the British Columbia Cancer Prevention Campaign.1 The five modifiable risk factors for cancer are: tobacco control, body weight, diet and alcohol control, physical activity and sun protection. Obesity and physical inactivity are associated with colon and breast cancers in magnitudes similar to those of stroke and coronary heart disease in Canada (Tables 1a and 1b).2-4 In a prospective 24 year follow-up of 116,564 US women aged 30-55, overweight and inactivity together accounted for 21% of premature deaths from cancer in nonsmoking women.5

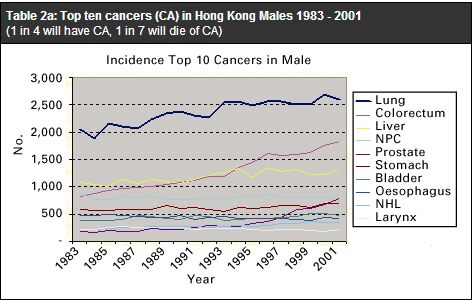

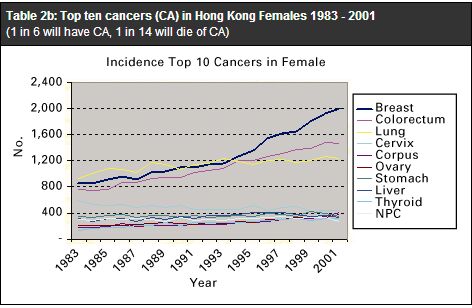

The Seven Steps cancer prevention message of the Canadian Cancer Society advised the public to get to know their body, not to ignore the warning signs of cancer, to visit the doctor if there is any change in their normal state of health, to follow screening guidelines and lead a healthy lifestyle.6 Useful websites are www.cancer.ca, www.bccancer.bc.ca and www.preventcancer.ca, with information not only in English but also in Chinese and other languages. As family doctors, we do well to promote these simple concepts to our patients and their carers. Cancer statistics in Hong Kong One in 4 Hong Kong males will have cancer and 1 in 7 will die of cancer, compared to 1 in 6 and 1 in 14 respectively for females.7-9 The top ten cancers are shown in graphs 1 and 2 (Tables 2a and 2b).7-9 This article will only discuss the commonest cancers with rising incidence.

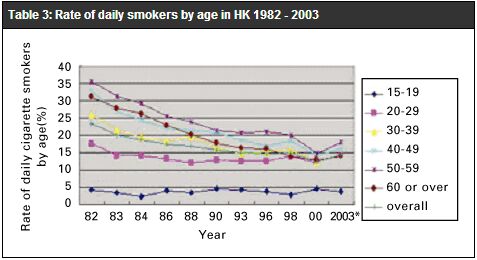

Immunizations to prevent cancer Universal Hepatitis B vaccination for newborns has been implemented in Hong Kong since November 1988. The age standardized incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma has been decreasing,9 and is to be expected in future as a result of the immunization programme.10 The new HPV vaccine11,12 The newly introduced human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine (Gardasil) is approved for prevention of infection for girls 9-26 years old, and is given at 0, 2 and 6 months. HPV can cause cancer of cervix, vagina, vulva and anus. The HPV 16 & 18 vaccine can prevent >35% of LGIL (low grade intra-epithelial lesions), >70% HGIL (high grade) and invasive cancer of cervix.12 The HPV 6 & 11 vaccine prevents genital warts and an additional 12% of LGIL12 Natural HPV infection only produces type specific cellular immunity, while the vaccine stimulates humoral antibody production to titres >50 fold higher. Hence, the vaccine can still be beneficial if a woman was infected by one type of HPV. But by the age of 26, most women studied were already exposed to the virus. Regular pap smears are still required after vaccination, as cancer of cervix can be caused by other types of HPV. The need for boosters, or whether the vaccine can be extended to protect males who have sex with males, awaits further study. The following advice still holds true: consistent use of condoms, avoid multiple sexual partners and partners who have had multiple sexual partners, no smoking and regular pap smears. Lung cancer Lung cancer remains the cancer having the highest incidence and mortality in Hong Kong. Fortunately the age standardized incidence has decreased from 84.6 to 60.4 per 100,000 between 1983 and 2000.9 Primary prevention is much better than screening or treatment for this cancer. A big step forward in tobacco control has been made in that from January 2007, smoking is prohibited in restaurants and workplace. Nonetheless, it is disconcerting to note that the rate of daily smokers has slowly increased again after two decades of decline (Table 3).13

There is strong evidence for offering smoking cessation advice at every teachable moment by as many health care providers as possible. Pooled data from 17 trials of brief physician advice versus no advice revealed a small but significant increase in the odds of quitting (odds ratio 1.74, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.48-2.05).14 The family doctor can use motivational interviewing techniques to engage smokers to contemplate and take actions to quit. Frequent screening with chest x-rays is associated with an 11% increase in mortality from lung cancer compared with less frequent screening (RR 1.11, 95% CI: 1.00-1.23).15 A recent study showed promise for improving survival with low dose spiral CT screening.16 Of 412 stage I cancers detected from 31567 first screens and 27456 repeat screens 7-18 months later, the 10 year survival rate was 88% (95% CI 84-91), and 92% (95% CI 88-95) for those 302 who had resection within one month. However the study was not a clinical trial. In addition to cost, "the radiation associated with repeated CT scans is not trivial,..... as 20% required follow-up CTs."17 "The unintended negative consequences of screening are of particular concern."17 Patients may continue to use tobacco after negative lung cancer screening, and thereby increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases and other smoking-related malignancies. Two randomized controlled trials that look at all-cause mortality from lung cancer screening are underway. Breast cancer Although the overall incidence of breast cancer is lower compared to Caucasian countries, Hong Kong has the highest breast cancer incidence in Asia.18 The age specific incidence has been increasing yearly by an average of 3.6% between 1973-1999.18 "The rise in relative risk was linear in successive birth cohorts, showing a 2-3-fold difference when comparing women born in the 1960's with those born around 1900."18 Breast self examination has not been shown to be effective in reducing breast cancer mortality, but it increases the number of breast biopsies because of false-positives. It should no longer be taught routinely.19 Women are to be advised of "breast awareness" and to report to their doctor if they notice any change or a lump. Mammogram screening is recommended by Canadian, US, Australian, UK and Japan health authorities, at least for women aged 50-69.9 It has been demonstrated to reduce cancer mortality by 15-20% in western populations, with absolute risk reduction of 0.05% in a Cochrane Review20 of 7 trials totalling 0.5 million women followed up for 13 years. However, it also increases unnecessary diagnosis and therapy by 30% (absolute risk 0.5%). For every 2000 women invited for screening in 10 years, one will have her life prolonged, but 10 healthy women will have unnecessary cancer diagnosis and treatment which would not improve her life span.20 The number needed to screen to prevent one woman from dying of breast cancer in Hong Kong was estimated to be 744 at a cost of 6 million dollars in 200421 or 1302 healthy women screened annually for 10 years in 2002, with absolute risk reduction of 0.106% over a 13.8 years screening period.22 The absolute risk of women dying from ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is low (1.9% within 10 years). The complication rates of fine needle aspiration and open biopsy are 8-10%. Leung et al22 and the Cancer Expert Working Group9 therefore opined that there was insufficient evidence to justify population-based mammography screening for Asian women, with their denser breasts and lower prevalence of cancer. However, case finding and mammogram is justified for those at high risk. While awaiting further studies in Asia, family doctors should be alert for women at high risk and advice them on primary prevention and the benefits of mammography, i.e. those with previous history of breast cancer, with family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer, especially if they are obese and physically inactive. Clinical breast examination (CBE) is easily done in the office and may detect some cancers missed by mammography, but the sensitivity reported in the community is lower (28% to 36%) than in randomized trials (about 54%).23,24 We can offer CBE when women come for pap test, and use that context to advice and promote breast cancer awareness. Cervical cancer The number needed to prevent decreases with increasing age. The Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists recommends two initial annual smears and then repeat smears at 3 yearly intervals, for women aged 25-64.25 Pap smear screening should be continued in women after they have reached menopause. It should also be done in women over 65 who have been sexually active in the past but have not been screened according to standard protocol. Those who had hysterectomy for fibroids do not need further tests. Colorectal cancer Age-standardized colorectal cancer incidence has been rising in Hong Kong, from 33.8 to 39.1 per 100,000 for males, and from 26.6 to 29.4 for females, between 1983 to 2000.7-9 Age standardized mortality has remained relatively the same during this period. Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third commonest cancer and second common cancer death in Canada. However, death rates have declined in both sexes there by 30% between 1973 and 2001.26 Incidence rate has also declined in Canadian women in the past 20 years. Canadian guidelines recommend yearly faecal occult blood testing (FOBT) in 50-75 years olds with average risk, plus optional flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5-10 years.27,28 The Ontario government has just announced a 5 year screening programme for 50-74 year olds using home FOBT screening kit.29 For those with moderate risk, i.e. cancer in first degree relative and <55 years old or cancer in 2 or more first degree relatives of any age, Canadian guidelines recommend colonoscopy every 5 years from age 40 or 10 years before the age of onset in the relative. For those with cancer in first degree relative over age 55, recommendation is for colonoscopy every 10 years from age 40. Referrals for genetic screening and specialist follow-up is recommended for those with familial adenomatous polyps (FAP) or hereditary non-polyposis colon cancers (HNPCC).28 Faecal occult blood test Cochrane review of trials on faecal occult blood test30 showed 16% reduction in mortality. For every 10,000 invited for biennial screening, only two-thirds will comply, 8.5 (95% CI 3.6-13.5) cancer deaths will be prevented over 10 years, 2800 healthy persons will have at least 1 colonoscopy and 600 will have 1 sigmoidoscopy and double contrast barium enema, with 5.2 perforation or haemorrhage. However, reanalysis of the systematic review data with updated trial results showed that the decrease in CRC mortality was off-set by the increase in non CRC mortality when all cause mortality was used as the outcome.31 Like other screening, the success of FOBT relies on a good infrastructure to support further diagnostic colonoscopy by clinicians with technical expertise. In 2004, the Cancer Expert Working Group concluded that there was insufficient evidence to demonstrate the effectiveness of mass FOBT screening in asymptomatic Hong Kong Chinese.9 However, large bowel surveillance with colonoscopy or barium enema was recommended for high risk individuals with first degree relatives having CRC before the age of 45 or two first degree relatives having CRC. Compliance of community subjects in China with FOBT has been found to be high (74%),32 but the specificity was low. Home administered FOBT has enhanced acceptance in a Taiwan study.33 Immunochemical FOBT has a higher positive predictive value (47%) than guaiac-based FOBT (18%),34 and dietary restriction is not required, but it is more costly. "FOBT remains the most affordable and possibly the most likely accepted method of screening that has good evidence for lifesaving, and maybe the only viable option for screening in China for a long time to come."35 In view of the rising incidence of colorectal cancer in Hong Kong, while awaiting further Asian screening trials, it is high time that we are more active in offering health promotion advice on diet and physical activity to prevent CRC, and discuss the pros and cons of FOBT with at risk patients. Persons with family history of colon cancer in 3 or more family members from 2 or more generations, one of whom with onset before 50, and/or associated cancers of endometrium, small bowel, renal pelvis or ureter, should alert the family doctor to the hereditary syndromes and trigger referral. Prostate cancer Prostate specific antigen (PSA) may be used for the monitoring of established cancer and metastatic disease, or as a diagnostic adjunct in combination with other tests for early detection of prostate cancer in symptomatic men. Its use as a routine population screening tool is controversial. The latest Cochrane review36 in May 2006 could only identify two screening trials and neither was assessed to be of high quality. There was no statistically significant difference in prostate cancer mortality between men randomised for screening and controls (RR 1.01, 95% CI: 0.80-1.29). Neither study assessed the effect of prostate cancer screening on quality of life, all-cause mortality or cost effectiveness. It therefore concluded that "there is not enough evidence to inform whether or not screening for prostate cancer, via either a digital rectal examination, PSA or transrectal ultrasound-guided (TRUS) biopsy, is more effective than no screening."36 The results from two large trials, to be completed in the next few years, will provide greater information on this issue. III. How to do it effectively Integrated preventive practice Cancer prevention can be integrated with cardiovascular risk and osteoporosis prevention. As cancers usually occur in middle age or older, a comprehensive protocol for an average risk middle aged to elderly patient would likely include:

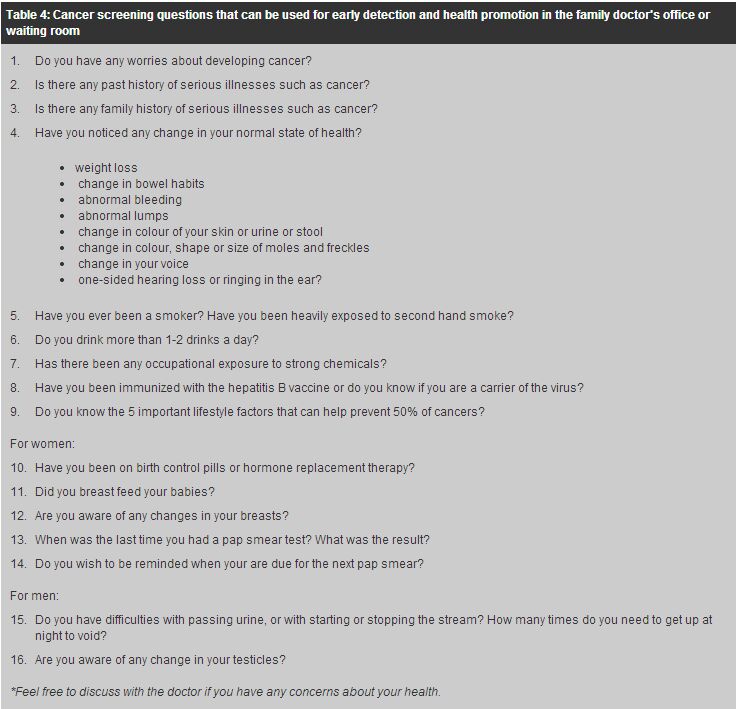

Facilitating cancer prevention in the office The principles of chronic disease management can be applied to cancer care and prevention. Good outcomes in chronic disease management are found in clinics that are well structured with standard protocols, clear records, patient recall system, and provision of structured patient education.38 Opportunistic screening and anticipatory care can only be provided in a busy practice if the physician's knowledge and skills are applied in a regular and systematic manner. The contribution of the whole team, including receptionist, clerk, nurse, dispenser or pharmacist is required. Reminders for health care providers can be in the form of chart stickers, checklists and computer prompts. Many office tools are available for education. Posters, pamphlets and audiovisuals can be shown in the waiting area. A particular slogan can be displayed each month. Patients can be introduced to the cancer hotline (2637 1122) and websites from local and overseas cancer centres, and empowered to discuss with the doctor about cancer concerns. Women can be invited to register with the Department of Health cervical smear programme. A questionnaire (Table 4) can be given to patients to fill out as a tool for cancer prevention advice.

Conclusion Cancers are major causes of mortality in Hong Kong. Family physicians have an important role in diagnosis, prevention and ongoing care of cancer patients and their families. Screening guidelines may change as newer evidence comes to light. Family physicians can access local and overseas information resources to update their knowledge. Practice organization and structure will facilitate delivery of appropriate cancer prevention. Key messages

Cynthia S Y Chan, LMCHK, MD (Canada), FHKAM (Family Medicine), FRACGP

Specialist in Family Medicine Correspondence to : Dr Cynthia S Y Chan Emaik : chansyc.hk@gmail.com

References

|

|