|

September 2005, Volume 27, No. 9

|

Original Articles

|

A case study of perceptions about smoking and smoking cessation interventions among members of an uniform disciplinary force in Hong KongDouglas T C Lai 黎達洲, Dominic M W Lau 劉敏維 HK Pract 2005;27:286-293 Summary

Objective: To determine the perceptions about smoking and smoking

cessation interventions among members of an uniform disciplinary force in Hong Kong.

Keywords: Smoking, Smoking cessation, nicotine replacement therapy, disciplinary force, primary care. 摘要

目的: 確定香港記律部隊成員對吸煙和戒煙措施理解。

Introduction Tobacco smoking is the single largest preventable cause of death in the world.1 In Hong Kong, although the prevalence of daily smokers has been decreasing steadily since 1982, smoking still kills over 5600 people every year, or 15 people per day.2,3 In 2003, there were about 819,700 daily smokers in Hong Kong, of whom 86% were male.4 More than 34% of smokers in Hong Kong had tried but failed to quit.4 Of those who had never attempted to quit, more than 17% expressed the intention of doing so.5 Reasons for continuing smoking are often complicated and involve individual attitudes, ideas and personal experiences. Understanding these may help health care workers find more effective ways to help. The purpose of this study was to understand participants' beliefs about smoking and their experiences with smoking cessation services. Method We recruited a total of 32 uniform officers who voluntarily attended a smoking cessation talk organized by the disciplinary force and the Tobacco Control Office of the Department of Health. The participants were divided into four focus groups. Each group consisted of eight participants, led by one trained facilitator and one recorder (each either a doctor or a nurse). We used four board topics for discussions. The questions were derived from a review of the relevant literature and discussion among research team colleagues. The four topics included (1) perceived difficulties in quitting smoking; (2) past experiences with quitting; (3) past experiences with anti-smoking health services and (4) anti-smoking services needed. Subjects were encouraged to say what they felt. Their views were recorded in Chinese as far as possible and were later translated into English by the interviewers. The interviewers were instructed not to express their own opinions during the discussion. The discussion lasted about one hour and was concluded by asking the participant to fill in a questionnaire with basic demographic data and smoking history. We did not audiotape the discussions. The results of the four focus groups were pooled together for analysis. The transcripts were reviewed by two individual researchers and main themes were identified. Quotations were selected to illustrate the views expressed. As this study was qualitative rather than quantitative, we did not present our findings numerically. Respondent validation was not undertaken in this study. Results

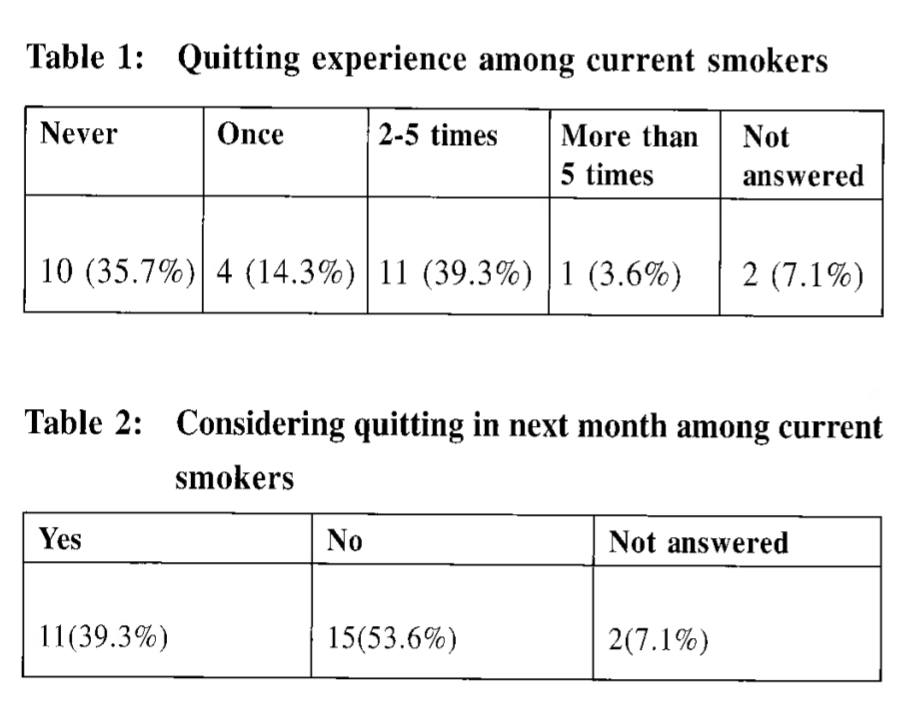

31uniform officers completed the questionnaire. 28 were current smokers and 3 were ex-smokers. All were male and most (84%) were aged between 30 and 50 years of age. The mean smoking duration was twenty years. Among the current smokers, most (97%) did smoke in the previous 7 days and 54% were not considering quitting in the next month. 36% had never attempted quitting, while about half of them had tried at least once (see Tables 1 & 2).

The most common response was that smoking has a socializing effect. Many participants noted that they were more likely to smoke when they were in the company of other smokers, or would smoke more at social gatherings.

A typical response was:

A few officers, on the other hand, mentioned that quitting resulted in noticeable

improvements in their exercise tolerance, better family relationships, chances of

promotion and conveyed a better image.

Many thought that they could quit on their own, but would do so at some later date. Antismoking service What they wanted ............

Most of the respondents expressed the need for conveniently located antismoking

services with hours that extended to outside normal office hours:

Many noted that the ideal antismoking service would be a one-stop service, with

pre-check, necessary investigations (e.g. chest radiography), doctor's consultation

and medications dispensed all at the same visit.

Some participants felt that they would find it motivating if there were some reward

for quitting, such as a certificate, souvenir or recognition from superiors. Some

suggested that it would help if they were excused from duty in order to participate

in smoking cessation programmes.

Many officers commented that information was most helpful when it involved real-life

examples, risks figures and encouraging success stories: Discussion There is evidence that smoking is more common in the disciplinary forces than in other sectors of society.6 For this reason, this study targeted a disciplinary force, with a view to exploring its members' perceptions around smoking. The evidence-based approach to helping patients quit smoking involves (1) brief advice by a physician, (2) nicotine replacement therapy and (3) antidepressants such as bupropion.7 Many of the subjects in this study lacked motivation, due perhaps to lack of confidence in their ability to quit, inadequate support services or not knowing how to access them. Studies have shown that brief (less than or equal to 5 minutes) advice on quitting given by physicians to smokers during an office visit results in higher quit rates compared to no advice.8 Although success rates are better with more intensive counselling, brief interventions appear to be more feasible for family physicians, given the time constraints and the reluctance of many patients to enter intensive programmes.10 The Stage of Changes model conceives smoking behaviour change as a process involving movement through a series of five motivational stages, including precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action and maintenance. Interventions based on this model have been shown to enhance motivation11 and predict cessation.12 For patients unwilling to quit, it is helpful to identify the reasons for resistance. For example, the family physician can dispel the myth that smoking improves concentration and explain the addictive nature and withdrawal effects of nicotine. Patients willing to make an attempt to quit should be given specific advice about how to proceed, including setting a quit date and information on the various pharmacological treatments available. Many respondents believed that willpower alone is sufficient for successful quitting. Some believed they would have no difficulty quitting when they chose to. These beliefs might reflect a lack of understanding of the addictive effects of nicotine. Cigarette dependence is a chronic relapsing condition.13 Many smokers must repeatedly struggle to achieve long-term abstinence. The use of NRT results in at least doubling the quit rate. For example, a meta-analysis of 17 randomized trials estimated the efficacy of the nicotine patch as 27% at the end of treatment and 22% at 6 months compared with 13% and 9%, respectively, for placebo.14 Smokers willing to quit should be offered NRT to increase the success rate. Limitations and further study One of the limitations of this study was that all of the uniform officers who attended were male. In the future, it would be helpful to explore the views of female officers. As the subjects were recruited voluntarily, the sample might not be representative. A larger scale qualitative study might give further insights into people's perceptions about smoking and smoking cessation. Conclusion In summary, a practical way of helping smokers who are willing to quit involves brief advice and the use of NRT as the first line treatment. Family physicians are in a particularly good position to provide this service to busy patients who can consult only outside regular office hours. There are in addition many organised smoking cessation services in Hong Kong. A complete list can be found on the Tobacco Control Office, Department of Health website (www.tobaccocontrol.gov.hk). Acknowledgement Special thanks to the following: Dr Luke CY Tsang, Consultant, Dr Kelly LC Choi, Dr Lam Wing Kwun, Health Promotion Committee, Professional Development and Quality Assurance, Tobacco Control Office, Department of Health. Key messages

Douglas T C Lai, MBBS(HK), FHKCFP, FRACGP, DDME (CUHK)

Medical and Health Officer, Chai Wan Families Clinic. Dominic M W Lau, MBChB(CUHK), FHKCFP, FRACGP, DOM(CUHK) Medical and Health Officer, Professional Development and Quality Assurance, Department of Health. Correspondence to : Dr Douglas T C Lai, Chai Wan Families Clinic, 1/F Main Block, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong.

References

|

|