|

August 2003, Volume 25, No. 8

|

Original Articles

|

An outcome analysis of chest x-ray examination for detecting severe acute respiratory syndrome in general practiceD Y N Young 楊應南, B W K Lau 劉偉楷 HK Pract 2003;25:357-362 Summary

Objective: To investigate an entirely new disease phenomenon for

which there has been no clear-cut diagnostic protocol for physicians working in

the community to manage flu-like illnesses which could simulate or be simulated

by SARS.

Keywords: SARS, Hong Kong, General Practice, chest radiology, clinical anxiety. 摘要

目的: 研究一個全新的疾病情況,在目前並沒有明確的診斷流程給予社區醫療人員依從以診治可模仿流感或被流感模仿的非典型肺炎。

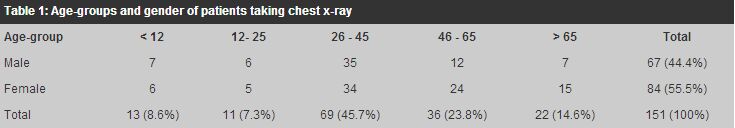

Introduction It is now global knowledge that a new virus has made its formal debut in Asia and has mounted an appalling blitz across the world.1-4 The novel disease has been named by the World Health Organisation the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). To the horror of all, this illness was within weeks looming as a globe-girdling disaster and taking a high toll of lives wherever it hit. In view of the SARS outbreak, the local medical practitioners have learned to adopt a different strategy in managing their patients. In keeping with the routine practice in the A & E Department of district hospitals, in the clinic of the first author (D.Y.N.Y.) who was the district coordinator in a SARS-screening programme, all patients who presented with a "flu-like" illness were advised to take a chest x-ray first before being interviewed for detailed medical history and examined physically for signs of a definable disease. This was practised at this extraordinary time because, on the one hand, more clinical information would have been available by the time of interview, and on the other hand, one of the cardinal features, and thus the diagnostic criteria, of SARS was chest x-ray infiltration. If the x-ray film of the patient seeking consultation showed any radiological abnormality suggestive of pneumonic change, particularly infiltrates giving a hazy appearance in the lung fields, blood tests would be taken either at the same consultation or in a follow-up visit, which would include, as far as possible, complete blood counts, liver and muscle enzymes and others. The tests were intended to establish a more complete clinical picture, which would help to ascertain the possibility of the presence of SARS and assess the extent of the pathology. For those presenting negative radiological findings, standard management protocol, which included bed rest, adequate fluid intake and rest in addition to careful observation for the next few days, would be applied and patients in this group would be treated as being afflicted with "ordinary" flu. Nevertheless, vigilance would still be placed on this group of patients by watchful observation. All confirmed cases of SARS or other serious diseases that required tertiary or specialist care were to be transferred to public hospitals for definitive management. Chest radiology as a screening tool Chest radiology as a screening tool for detecting diseases has a long history.5 As early as forty years ago, a group of 50,000 men participated in a mass x-ray programme to screen for lung cancer.6 Even in a recent editorial, regular radiological surveillance of asymptomatic smokers for early detection of lung cancer was justified.7 In Japan a system of tuberculosis case-finding by mass chest miniature radiography was set-up in the 1990's.8 In India, examined in the context of statistical reliability of tests, the methodology of prior x-ray screening adopted by the District Tuberculosis Centre for case-finding for tuberculosis appeared to be well founded.9 In Hong Kong with a population having a relatively high tuberculosis notification rate and high prevalence of active tuberculosis in nursing homes, tuberculin skin testing did not appear to be a useful screening method in a study involving 587 subjects, but a positive chest x-ray followed by sputum smear and culture enabled an estimated prevalence of active tuberculosis to range from 1.2 to 2.6%.10 For asbestos-induced diseases in Finland, screening with chest x-ray was carried out in 18,943 workers who had been exposed to asbestos and was a preliminary survey to prompt further national follow-up on these workers.11 In Japan, among 2,951 construction workers exposed to asbestos occupationally, 168 (5.7%) were found to have significant findings of pleural plaques or pulmonary changes on chest x-ray.12 From this it can be seen that radiology is, in appropriate circumstances, considered an useful and suitable screening method for detecting diseases or pre-disease states. Objectives The objective of this evaluation exercise was in the first place to evaluate the outcome of adding on an investigational procedure of chest x-ray to the diagnostic process at the first contact of medical consultation of a febrile "flu-like" illness which could have been an atypical pneumonia or Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome in its early or undifferentiated stage, and thus an emergency condition demanding immediate attention and appropriate management in all areas including reporting to the authority, a referral to the district treatment centre and ensuring all-out antiseptic measures in the clinic. Needless to say, thorough and all possible infection control routines had always been undertaken from corner to corner in the clinic, for the sake of both patients and the staff. It was hypothesised that with the inclusion of the result of a chest film, a more reliable clinical diagnosis could be arrived at more readily, quickly and accurately, without slips in making diagnosis, delay in giving appropriate treatment or making prompt referral. The second objective was to estimate the prevalence of this condition, bearing in mind, the sample came from a general practice clinic. Method of study The study period spanned from 20 March to 30 April 2003, when the outbreak ran at a breakneck speed and the public was under a cloud of disquietude, almost of panic proportion. This was a purposeful endeavour as a radiological investigation was in any event a useful and a necessary tool in ensuring a more reliable diagnosis of a condition which could carry dire consequences if it was missed or overlooked, and above all, patients were then exceptionally willing and ready to subject themselves to a recognised and publicised investigatory method with which they hoped to eventually allay their anxiety. The inclusion criteria for asking a patient to have a radiological screening were two or more of the following "flu-like" symptoms: persistent fever higher than 38 degrees Centigrade, new onset of or persistent cough, unexplained lethargy, muscle pain, sore throat, running nose, severe headache or loose bowel. The chest x-ray was taken in the clinic while the patient was waiting for his or her turn for clinical interview. As this was an acute medical situation during the said period, for the purpose of fast-track processing akin to that in an emergency room, the x-ray film was initially and promptly interpreted by the first author who had had the experience of reading chest x-ray for more than fifteen years. This had the virtue of avoiding to keep the patient concerned waiting for longer than necessary in the common waiting room. Depending on the radiological finding, the patient would be subsequently managed as a case of "ordinary" viral illness or accordingly suspected, or presumed until proven otherwise, to have the SARS disease. The latter patient would be sent immediately to the A & E Department of a district hospital for further investigation and management. The aim of the exercise was to identify a suspected case as soon as possible, then segregate him or her from other patients. Results 1,161 patients attended the clinic during the period and a total of 151 patients, making up 13% of those seeking consultation, came in presenting with a "flu-like" illness and thus fitting the criteria of the study. All 151 patients, or 100%, agreed to take a chest x-ray to confirm or hopefully exclude the diagnosis of SARS. Indeed, many of these patients requested for some kind of investigation not because of the severity of their malaise, but were driven simply by their worry, for example, after having had remote social contact with hospitalised cases and merely suspected "spatial" contact, such as living or working in the same building as those of admitted cases. Hence, the sample represented the entire target population. It was expected that bias would therefore be minimum. A breakdown of the studied population was shown in Table 1, with 13 patients under 12 years of age, 11 patients between 12 and 25, 69 patients between 26 and 45, 36 patients between 46 and 65, and 22 patients over 65. This indicated that there was a predominance of participants in the non-paediatric groups which seemed, at least in the public eye, to be particularly hit by the outbreak and were therefore vulnerable subjects. In reality, the reason of the clustering in the middle-age group was often that these were the ones who could afford further investigations beyond the routine consultation and who in fact made up the bulk on the patient register of the clinic.

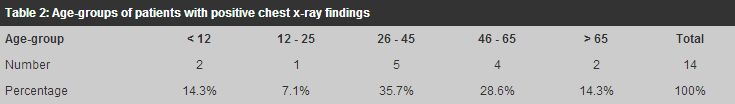

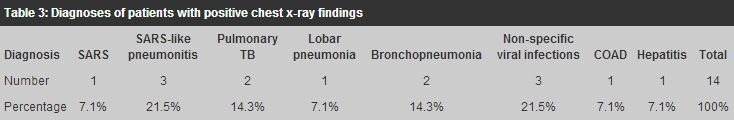

The gender ratio was 1:1.25 (male vs female), which was comparable to the usual female predominance in the clinic patients seeking consultations. Out of these 151 patients, 162 chest films were taken, including 11 films which were follow-up ones. Overall, some kinds of radiological abnormality ranging from opacities to streaks were found in 40 patients, yielding a positive rate of 26.49%. Of the 40 patients with positive x-ray findings, four were suspected to suffer SARS in view of the characteristic haziness in the lung fields suggesting infiltrates of an interstitial and/or alveolar nature or opacities of a ground-glass or reticular pattern.13-15 All of them were referred to the A & E Department of the Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital. Of the four, a 42-year-old Filipino worker was subsequently confirmed to have SARS. The other three were later observed, investigated and treated as non-SARS patients. Fourteen cases, including the SARS and the 3 SARS-like cases, were subsequently given a diagnosis: (Table 3)

The remaining 26 patients, who had some radiological abnormalities, did not receive any definitive clinical diagnosis apart from problem-focused tentative formulation, such as "pyrexia of unknown origin" or dizziness of unknown cause, as was a common practice in primary care. Apart from the SARS patient, all other 150 flu-like patients were also followed up closely, or at least, their conditions were monitored over the phone in the two weeks following until they had totally recovered from the illness or their pyrexia had subsided. None of the patients who had a negative chest film was eventually diagnosed to have SARS. Discussion The use of a clinical service that could help to reach a diagnosis and provide hints in working out a management plan for "flu-like" illnesses or chest-related complaints was particularly welcome at this particular time of societal turbulence by both the doctor and patients alike. The psychological unrest of patients with any symptom hinting at an ominous cause such as SARS must be addressed to and every effort should be made to dispel their doubts apart from ameliorating their physical and mental discomfort. On the doctor's side, such an issue as uncertainty in clinical medicine often rules the day.16 This is particularly noticeable in the process of decision-making in general practice.17,18 As Baume19 said, many decisions and judgements are often made in the brief time in the doctor's office, and no doubt the situation is all the more acute and demanding in our clinics during the SARS period. It is no surprise that the doctor may feel more comfortable and confident with a chest x-ray in hand, in making a more accurate and directional diagnosis of a condition which could range from any benign entity to a sinister disease such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. With more objective clues and clinical signs, the doctor can confidently work out a relevant management plan for the patient who brings with him or her the normally run-of-the-mill viral or upper respiratory tract infections. It can hardly be overstated that with a disease like SARS which can masquerade itself behind anything but typical signs and symptoms of pneumonia, a doctor needs more than the average level of exactness and a usual dose of confidence. With a simple x-ray service in his or her armamentarium, a family physician can be an effective gatekeeper to the hospital service and play an important role in the sentinel surveillance system.20,21 In this way, the family physician can serve the community in a steadfast professional manner by taking care of the vast majority of patients, say 99%, within his or her expertise and sending only the few, less than 1%, needy ones to the hospital. It is impossible for the hospital to handle the surveillance of SARS in the entire patient population in the community, especially when it is realised that SARS may be here to stay for some time. p> LimitationsIt is acknowledged that even with the help of a chest-ray film, there still could well be some false-positive and false-negative cases. This is certainly true in the case of SARS where a flare of pulmonary infiltrates could only be shown up at one or more days later, and a negative CXR may create a sense of false security in both the doctor and the patient concerned. Yet, it appears from the current study that the risk of missing a diagnosis of SARS in a patient with a normal CXR was small in primary care. Meaningful and useful information can be derived from a chest x-ray film that can help the family doctor to decide to take up the entire management of the patient, or to seek expert help from the hospital or other specialists. The findings of the present study do not necessarily reflect in full the current situation, in particular the prevalence of the disease, but none the less they do shed light on the fact that in actuality the total number of suspected or confirmed cases of SARS represent only a small fraction of the whole patient population presenting with "flu-like" symptoms. Conclusion It has been borne out from the current evaluation exercise that at least one SARS case was picked up, thanks to the chest film. On the surface, there was obviously certain advantage in utilising x-ray as a tool in both screening and diagnosing SARS in the evolving stage before the full-blown state. The documented SARS patient, manifesting a seemingly non-threatening flu-like illness, would not have been identified if there were no chest film available at the consultation. After all, this new patient visiting the clinic for the first time might not return at all for follow-up and could have already infected an enormous circle of people coming into contact with him at home, in the workplace, on the way or in any unexpected venue long before he was finally properly diagnosed. It also appears from the study that the prevalence of this deadly disease is fairly low in the community but the importance of detecting it from among the patient population cannot be overstated, on the premise that one is always too many. Key messages

D Y N Young, MBBS, DCH, Dip Pract Derm

General Practitioner, B W K Lau, PhD, FHKAM, DPM, DCH Consultant Psychiatrist, St. Paul's Hospital. Correspondence to : Dr B W K Lau, St. Paul's Hospital, 2 Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong.

References

|

|