|

August 2003, Volume 25, No. 8

|

Discussion Paper

|

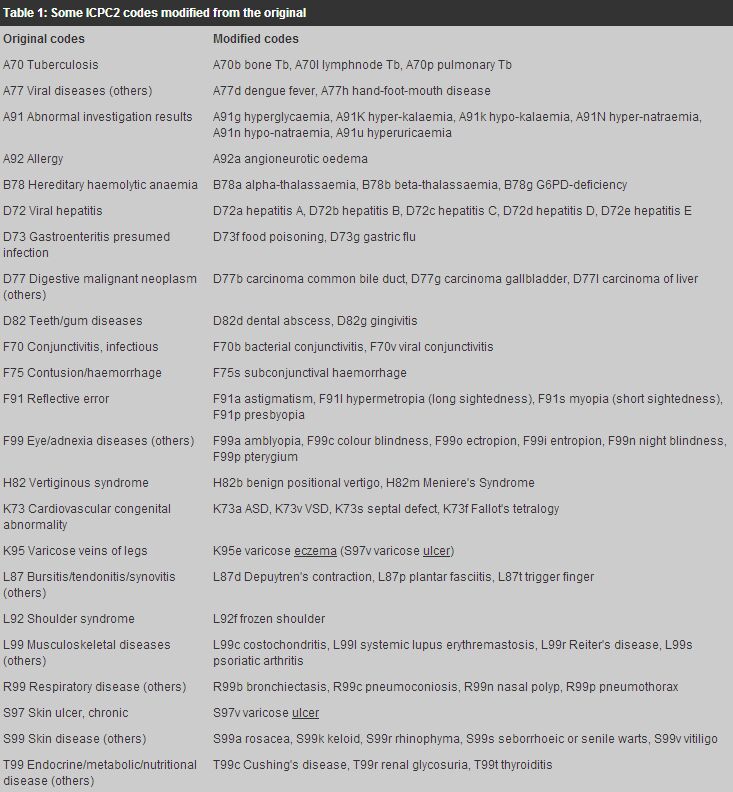

Modifying ICPCY T Wun 溫煜讚 HK Pract 2003;25:375-379 Summary The International Classification of Primary Care is used by family physicians in Hong Kong to code diagnoses. This coding system often lumps several related diseases into one code and many less common diseases do not carry specific codes. This paper presents a method of modifying some codes to make them more specific, by adding a letter as the fourth digit to the original three-digit codes. The method can expand a single code into 52 sub-codes and provides mnemonics to facilitate easy recall. The method needs further discussion, verification and standardisation. A list of selected codes illustrates the methodology and highlights a few codes that are easily confused. This paper also discusses the lack of motivation by local family physicians in using a coding system in their clinical work. 摘要 香港家庭醫生多採用基層醫療國際分類系統將診斷結果編碼。因為這套系統經常將幾種相關疾病編入同一編碼內, 而有些不常見疾病又缺乏特定編碼,所以本文介紹一套改良方法,即在現有三位數字編碼的後面, 加上英文字母成為四位數字編碼,這樣每個編碼就擴展為52個亞編碼,同時還可幫助記憶來使用。 當然,改良方法仍需要進一步討論、核實和實行標準化。在一覽表中,作者選擇了一些編碼對改良法加以說明, 並列出容易混淆的編碼。本文亦討論了家庭醫生在臨床工作中缺乏使用編碼系統的動力的問題。 Introduction The International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) is the system commonly used by family physicians (FPs) in Hong Kong who code their diagnoses. The ICPC has three drawbacks for the local profession. Firstly, there is no motivation for coding diagnoses. Physicians in some foreign countries use ICPC to code their consultations (reasons for encounter as well as diagnoses) in reporting to the authorities for reimbursement. In Hong Kong, FPs do not have to code their diagnoses except when the computerised record system requires such entries. Secondly, ICPC lumps diseases/problems infrequently encountered in family practice into one code, making the coding less specific, e.g. R99 for nasal polyp, pneumothorax, bronchiectasis, pneumoconiosis, and L99 for systemic lupus erythematosis, Reiter's Disease, psoriatic arthropathy. Thirdly, it is designed for universal use and hence a few diseases that are very common in a geographic region but rare elsewhere are not specifically coded, e.g. thalassaemia and glucose-6-phosphatase dehydrogenase deficiency in South Asia. When the second and third drawbacks occur together, the coding is even more non-specific, e.g. chronic hepatitis B. ICPC allows modification of its codes for specificity by adding a fourth digit to each code, e.g. L54 for plaster, L54.1 for casting plaster, and L54.2 for removing plaster (Chapter 5, ICPC-2).1 For a few codes, such modification is necessary to avoid confusion. Using a numeric as the fourth digit sometimes makes recall inconvenient, e.g. if R99.2 is for bronchiectiasis and R99.3 for pneumoconiosis, human memory may find it difficult to recall which is which. Physicians using manual records or those whose computer systems lack an intelligent search engine, would find a printed list of codes at their desktop a handy tool to find a particular code, especially those conditions that are lumped under groups like hereditary haemolytic anaemia (B78) or conditions that are prone to confusion such as acute lymphadenitis (B70) and acute lymphangitis (S76). This discussion paper presents the author's proposed method of modifying some ICPC2 codes and suggests a handy list of codes for easy desktop reference. One method to modify ICPC2 codes As a code represents a name, e.g. L for "locomotive system", a letter instead of a numeric could be a better way to represent specific diseases. Viral hepatitis is coded as D72 and D72a to D72e could thus be used to specify virus hepatitis A to E. D72b represents either acute or chronic hepatitis B that can be distinguished from the date of diagnosis; an active problem of D72b coded six or more months ago is chronic hepatitis B. Similarly, R99b stands for bronchiectasis, R99c for pneumoconiosis, R99t for pneumothorax and R99n for nasal polyp. The following table (Table 1) is a selected list of modified ICPC2 codes. This list is only meant to be a reference for drawing up a "handy list". It highlights a few codes that are not obvious and are easily confused in the ICPC2 tabulated list. It also illustrates the proposed modification of some codes. Readers should note that the list is drawn from Component 7 (diagnoses/diseases) of ICPC2, not from ICPC that is still being used in most family practices in Hong Kong. Each family physician is likely to have individual preference or necessity for a much shorter list.

Discussion ICPC is designed and well-suited for primary care. It codes reasons for encounter that are often intricately hidden in first-contact consultations. The codes often represent non-specific conditions (e.g. "viral exanthem, other", "viral disease, other") that are very common in the undifferentiated first contacts. However, as an episode of illness develops, patients' problems unfold and become clearer and more specific. For example, a patient may come to us for "yellowish skin" (D13) and we make a diagnosis of viral hepatitis (D72). We do some tests or refer the patient to hospital for further investigation and hepatitis C is finally diagnosed. At this stage, the code D72 needs specification. Also at this stage, consensus on the specifications is much needed and is essential for future exchange of health data. It is useful to have a note on the few conditions that are easily miscoded. Hyperuricaemia (A91) is not coded under locomotor system (L) or endocrine system (T), deafness in one ear (H28) is certainly different from deafness in both ears (H86), varicose eczema is K95 not under skin (S) though varicose ulcer (S97) is, senile wart (S99) is different from simple wart (S03), and sunburn (S80) is not burn/scald (S14). Letters as mnemonics aid recall better than numbers. They also allow more potential sub-divisions; -99a to -99z allow 26 specifications (52 if capital letters are also used) while -99.0 to -99.9 allows 10. This larger capacity is most useful for the "dumping bag" of -99's. It is advisable to make a specification that can be mapped to a single ICD-10 code (International Classification of Diseases used in secondary care) so that codes in primary care are interchangeable with those in hospitals. This modification has the potential of further expansion, e.g. into -99aa or -99a1. One possibility is using "0" and "1" to denote inactive or active problems, e.g. D72b1 as current chronic hepatitis ("carrier"), D72b0 as past infection (positive HBsAb). For an average FP in practice, the number of ICPC codes requiring specification is small. But for the health authorities or organisation policy-makers, the number is much larger, particularly if mapping with ICD-10 is needed. Individual FP can make a short list of modified and useful ICPC codes with little effort and time. Using alphabet as the fourth digit to specify a disease within an ICPC2 code is however a rudimentary concept and is hereby open for further discussion and modification. It also needs pilot testing for feasibility and practicability. In Hong Kong, the big barrier of coding problems or diseases in primary care is lack of motivation (the first drawback mentioned earlier). The primary and most important use of classifying and coding diseases is for data analysis and health planning, and ultimately for quality care. Policy makers and health administrators find these data important but frontline clinicians do not see the imminent nor immediate usefulness of coding diseases. Indeed a family practice could run their daily work smoothly without any coding. There is no information on the proportion or type of local family practices that are coding their diagnoses. There is also no study on local FPs' motivation and difficulties in coding. Our knowledge in this aspect of local practice is very limited. Coding problems/diagnoses is essential for quality care. It is very useful in the effective maintenance of a disease-register,2 in medical audits and studies on morbidity.3,4 If computerised medical records are used, diagnostic codes are indispensable. For a FP in solo practice who is not going to do clinical audits or to use computerised medical records, there is hardly any motivation or necessity for coding. Even clinical audits may not always require retrospective retrieval of medical records for an index-disease. The best way to motivate these FPs to use disease coding is computerisation of medical records. Within and among group practices, sharing of information requires accurate and efficient coding. Good record keeping is part and partial of a consultation, demanding perseverance and time. In busy practices, there is often not enough time for checking and updating medical records. The frontline clinicians would put coding very low in the priority list of their daily duties. Health administrators in group practices should ensure and facilitate accurate and comprehensive record keeping, particularly if they want to make good use of health data. Clinicians should be supported by being given enough time to write, maintain and update good medical records, including coding. In this aspect, little can be expected from a 6-8 minutes consultation. Any FP who wishes to have an electronic version of ICPC2 list can visit the Family Practice Online for a copy at http://fampra.oupjournals.org/cgi/content/full/17/2/101/DC1 or the temporary website of the WONCA International Classification Committee at http://docpatient.net/wicc/wiic_map.html (both URLs as accessed in June, 2003). Conclusion Modifying ICPC2 codes is necessary for specific conditions as undifferentiated problems unfold in primary care. Expanding some codes with a letter as the fourth digit is a simple method of modification but needs universal standardisation and verification in near feature. Key messages

Y T Wun, MBBS, MPhil, MD, FHKAM(Fam Med)

Member,Research Committee The Hong Kong College of Family Physicians. Correspondence to : Dr Y T Wun, Research Committee, HKCFP, Room 701, HKAM Jockey Club Building, 99 Wong Chuk Hang Road, Hong Kong.

References

|

|