|

September 2002, Volume 24, No. 9

|

Update Article

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Systemic lupus erythematosus: when to refer?C C Mok 莫志超 HK Pract 2002;24:444-449 Summary Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complex disorder with variable presentation, disease course and prognosis. As the prevalence of the disease is around 0.1%, most primary care physicians and general internists may not have sufficient experience in the management of moderate-to-severe life-theatening disease manifestations. However, patients with mild stable disease may be well managed by family physicians who are equipped with knowledge of the disease. The major tasks of the primary care physician in the management of SLE include early diagnosis, appropriate referral, monitoring of patients with mild stable disease, psychological support and collaboration with the specialists in the management of severe disease. 摘要 系統性紅班狼瘡是一種複雜的病症,其臨床表 現、病程和預後變化多端。發病率約千分之一。大多數基層醫生雖然缺乏治療中度及危害生命的重症病人的經驗,但對此病有足夠知識的基層醫生可以治療穩定的輕症患者,包括及早診斷、適時轉介、為穩定病人進行定期監測,提供心理支援以及與專科醫生合作治療嚴重患者。 Introduction Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystemic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology. The disease predominantly affects women of childbearing age, with a female to male ratio of approximately 9:1 in all ethnic groups. Although SLE may develop for the first time in patients after the age of 50, this is rather uncommon.1,2 A local survey of 640 SLE patients from Queen Mary and Tuen Mun Hospital revealed that the commonest age of onset of the disease was between 20 and 45 years (Figure 1). Less than 8% of patients had first onset of SLE after the age of 50.

Patients with SLE often develop distinct immunologic abnormalities, which include the antinuclear, anticytoplasmic and antiphospholipid antibodies. Genetic, immunologic, hormonal and environmental factors are involved in its pathogenesis.3,4 The prevalence of SLE ranges from 15 to 52 per 100,000 persons in Western countries.5 In mainland China, the estimated prevalence of SLE is 0.1% (personal communication, Huaxia Congress at Shanghai 1999). However, there is still no formal epidemiological survey on the prevalence of this disease in Hong Kong. As most patients with moderate to severe disease manifestations are being managed in hospital settings, most primary care physicians and general internists may not have sufficient exposure to this not uncommonly encountered disease. The clinical manifestations of SLE are extremely diverse and no two patients are exactly alike. The course of the disease is variable and is characterised by periods of relative quiescence and exacerbations, which may involve any organ or system in various combinations. New clinical features may develop throughout the disease course. An important example is renal disease, which occurs in around 27% of patients at presentation, but the prevalence increases significantly to 45% after a mean follow-up of 45 months.6 As nephritis is an important cause of morbidity in patients with SLE, routine screening for renal disease is mandatory during follow up visits. The prevalence of various clinical features of SLE is shown in Table 1.7 In decreasing order of frequency, the commonest features are arthritis, malar rash, alopecia, renal disease, leucopenia and photosensitivity. As the majority of SLE patients initially present with joint and skin problems, general physicians should be aware of the diagnosis so that appropriate investigations can be arranged.

In addition to disease flares, many patients with SLE develop permanent organ system damage. This damage progresses over time and may be associated with significant morbidity and mortality.8,9 Although the prognosis of SLE has dramatically improved in the past few decades, mortality remains a major concern. In the pre-steroid era, less than half of patients with SLE were expected to survive for more than 5 years. With the availability of more potent immunosuppressive agents, antibiotics for the treatment of infective complications, the application of dialysis for patients with end stage renal failure, the 5-year survival rates of SLE patients are now more than 90% in most international series.10 A local study on the survival of SLE patients conducted in a tertiary referral center reported a 5-year survival rate of 93%.6 With the judicious use of immunosuppressive agents, stringent monitoring of disease activity and treatment-related complications, the local survival of SLE patients can be comparable to those reported in most other series in the world. SLE is an illness with multiple end-organ involvement. It is a major challenge to both the patients and their families. Patients with newly diagnosed SLE often have anxieties about a possible fatal chronic disease with unpredictable disease course and potential disability. Uncertainties regarding treatment options and their related complications further aggravate the stress of patients. These anxieties should be properly addressed during clinic visits. Moreover, pre-pregnancy counselling of the lupus couples concerning the optimal time of conception, the risk of disease flares, the chance of fetal loss and the safety of various anti-lupus medications should also be undertaken.11 Patients with SLE must learn how to cope with and monitor their own disease, and to assist the attending physicians in distinguishing coincidental unrelated symptoms from a genuine disease flare. Psychological support by either the physician and/or an appropriate health care professional is essential. SLE patients may require the expertise of other professionals such as the psychiatrists, ophthalmologists, dermatologists, nephrologists, cardiologists, orthopedic surgeons, occupational and physical therapists, and clinical psychologists. Not all of these are needed at the same time, and their coordination is best done by a specialist, usually a rheumatologist, who has considerable experience and knowledge of the disease. Role of the primary care physicians There are four main tasks of primary care physicians in the diagnosis and management of SLE. These are:

Making the diagnosis of SLE A set of criteria was published by the ACR for the classification of SLE (Table 2).13 Although the criteria were designed mainly for comparison of patients among various centers, they are also useful for evaluation of individual patients. When a patient fulfills 4 or more of

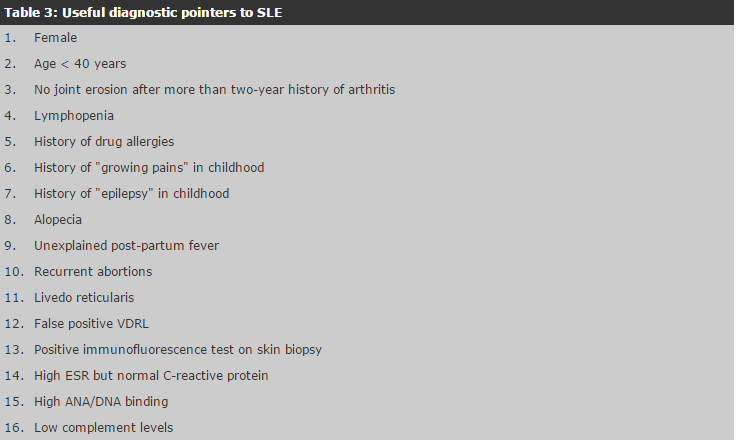

the 11 criteria serially or simultaneously, the diagnosis of SLE can be made with a specificity of around 95% and a sensitivity of 85%.14,15 If one meets less than 4 criteria, then SLE is possible and the diagnosis relies upon clinical judgement. The author would like to label these patients as lupus-like disease (LLD) and the monitoring for disease progression/conversion is no different from a patient with SLE. Recent observational study appears to indicate that patients with LLD belong to a subset of patients with good prognosis and the chance of conversion into SLE is low.16 Antinuclear antibody (ANA) is found in more than 98% of patients with SLE and is thus a very sensitive marker for the disease. However, it is non-specific and may be found in the normal population and in many other rheumatic disorders. ANA should therefore be regarded as a screening test before further investigations are arranged, and a negative result will indicate a very low probability of having SLE. Patients with ANA alone, without any other organ-system involvement of typical laboratory findings, do not qualify for the diagnosis of lupus. There are other laboratory tests which carry a higher predictive value than ANA and are more helpful in the diagnosis of SLE. Antibodies to double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) and Smith antigen (anti-Sm) are specific for SLE, though they are less sensitive than ANA. Antibodies against extractable nuclear antigens (ENA) (e.g. Ro, La, Sm, nRNP) and the phospholipids (e.g. anticardiolipin, lupus anticoagulant) are associated with certain manifestations in SLE and are particularly important during pregnancy counselling. A number of conditions may mimic early SLE. These include undifferentiated connective tissue disease, Sjogren's syndrome, primary antiphospholipid syndrome, fibromyalgia with a positive ANA, immune thrombo-cytopenic purpura, drug-induced lupus, reactive arthritis and early rheumatoid arthritis. Table 3 shows a list of useful diagnostic pointers to SLE. The presence of any of these features should alert the physicians to the possible diagnosis of lupus.

When to refer? Almost all SLE patients with anything more than stable mild disease should be taken care of by an experienced physician who, in most cases, is a rheumatologist. Those patients with mild disease may be managed by the family physicians who are well equipped with the knowledge of the disease and have a good communication network with the specialists and other health care professionals. Patients with mild stable SLE are those who have the following characteristics:

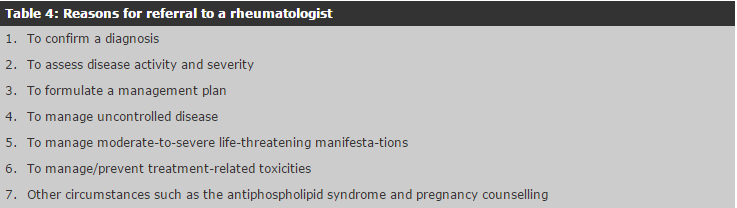

Table 4 summarises the indications for referral to a rheumatologist and/or other appropriate specialists.

Diagnosis of SLE can be difficult because of multisystem involvement and variability of presentations. Patients may also present atypically which pose a diagnostic challenge to the physician. Rheumatologists may be needed to interpret laboratory findings and confirm the diagnosis in suspected and doubtful cases. Assessment of disease activity and severity is important for the establishment of an appropriate treatment program for an individual patient. Patients with very active and severe disease may require on-going input from a rheumatologist. A number of validated disease activity indices are now available for clinical use to assess disease activity and severity.17,18 Patients who are referred to specialists are often thoroughly counselled, educated and given a treatment plan, which can be followed by the primary care physician if the disease remains stable and mild. For patients who have more serious manifestations, the rheumatologist may be required to coordinate care with other specialists and/or allied health professionals. Referral to specialists is also required when certain disease manifestations are uncontrolled. Examples are pleurisy, pericarditis and/or arthritis that fail to respond to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; rash not controlled with topical therapy, active vasculitis, severe Raynaud's and development of digital ulcers; myositis, central nervous system disease, continuing active renal disease or ongoing hematological manifestations not responding to corticosteroid treatment. Patients with major organ damage or in whom management or prevention of treatment-related complications such as osteoporosis, steroid-induced myopathy, avascular bone necrosis are needed should also be referred to appropriate specialists. Finally, referral is also needed under certain circumstances such as pre-pregnancy counselling and the management of the associated antiphospholipid syndrome. Monitoring of disease activity in SLE patients Monitoring of lupus activity is the major task of the attending physician during follow up visits. Enquiry on new symptoms and the search for new physical signs is important. Increasing arthritis, systemic upset such as fever, anorexia, weight loss, new skin rash, worsening alopecia should alert the physician to the possibility of a clinical flare. As renal disease is prevalent in SLE patients and carries significant morbidity, identification of early kidney involvement is essential. This can be achieved by routine testing of urine for protein by a dipstick in every clinic visit. A recent increase in proteinuria in a non-menstruating patient and in the absence of urinary tract infection warrants further investigation. Hypocomplementemia as a result of complement activation by immune complexes is common during disease flare in SLE. Although the serum level of complements may not necessarily correlate with disease activity in certain patients and organ/systems, it serves as a general guide to the activity of SLE. Single values of serum C3 and C4 level are seldom helpful and following their trend is far more informative. A dropping C3 and/or C4 level, together with new and compatible clinical findings, confirms the suspicion of a disease exacerbation. Management strategies of SLE The management strategy of SLE depends on the nature of the organ-systems involved and the severity and extent of the disease.19,20 In general, a more conservative approach is adopted for non-life-threatening manife-stations such as dermatological and musculoskeletal disease. A much more aggressive treatment strategy is necessary for serious manifestations like diffuse proliferative nephritis, transverse myelitis and pulmonary hemorrhage. It is beyond the scope of this article to describe in detail of the various treatment modalities for SLE. Conclusion Because of the relatively low prevalence of SLE compared to other medical diseases, many primary care physicians may not have sufficient exposure to this condition, especially when the manifestations are severe enough to warrant hospital admission. However, patients with mild stable SLE may be well managed by family physicians. The role of the primary care physician is to recognise and diagnose the disease early, initiate specialist referral when appropriate, monitor disease activity in patients with mild stable disease, provide psychological support and counselling, and to collaborate with the specialist in the management of moderate-to-severe disease manifestations.

C C Mok, , MRCP, FHKCP, FHKAM(Med)

Senior Medical Officer, Department of Medicine & Geriatrics, Tuen Mun Hospital. Correspondence to: Dr C C Mok, , Senior Medical Officer, Department of Medicine & Geriatrics, Tuen Mun Hospital, N.T., Hong Kong. References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||