|

September 2002, Volume 24, No. 9

|

Update Article

|

|||||

Scabies in the elderly: a revisitJ K H Luk 陸嘉熙, H H L Chan 陳衍里, N S L Yeung 楊心靈, F H W Chan 陳漢威 HK Pract 2002;24:426-434 Summary Scabies is caused by the mite Sarcoptes Scabiei. It is common in elderly populations especially among those with dementia, neurological disorders, malnutrition, infectious diseases, haematological malignancy and immunocompromised state. The mode of transmission is by direct skin-to-skin contact with infected individuals. Scabies is suspected when there are burrows or when patients have typical symptoms with characteristic skin lesions and distribution. However, it may present atypically in the older population. Various topical preparations can treat scabies effectively. Control of scabies outbreak depends on improvement in scabies recognition, awareness and prompt treatment of the disease. Family Physicians should maintain a high degree of suspicion and offer appropriate treatment without delay when necessary. 摘要

疥瘡是由疥 Introduction Scabies is an important public health problem in many parts of the world. In under-developed countries where poverty, poor hygiene, social deprivation and overcrowded conditions prevail, scabies is a widespread skin disease.1 In developed countries, scabies is not uncommonly found among infants, older patients, immunocompromised persons such as those suffering from HIV infection, and other patients with chronic medical problems.2 In the older population, it is usually associated with conditions such as dementia, neurological or mental disorders, malnutrition, infectious diseases, haematological malignancy and immuno-compromised state.1 Unlike other infectious diseases, scabies is not a notifiable disease and its prevalence in Hong Kong is not known. However, it was reported in the 1970s that scabies accounted for about 4 percent of the skin cases seen in the government dermatological clinics.3 This information to a certain extent reflects the scope of the problem in the outpatient setting locally. No study has been performed to document the prevalence of scabies in the older population locally, either in the community or those institutionalized. In Taiwan, it was reported that the prevalence of scabies among nursing home workers in southern Taiwan was 10.7%.4 The impact of scabies on the older population is often underestimated. While infestation with the scabies mite is not a life-threatening condition, the persistent generalised itchiness often results in much debility of and suffering the older patients and may even lead to depressive illnesses.1 Compared with other dermatological ailments, scabies is common in elderly population and effective treatment is available. Family physicians should have a good understanding of the presentation, diagnosis and therapeutic modalities of the disease. Biology and life cycle of Sarcoptes Scabiei

Scabies is caused by the mite Sarcoptes Scabiei (Figure 1). The adult mite is 1/3mm long and has a flattened oval body with eight legs. Infestation starts when a fertilised female mite arrives on the skin surface and excavates a burrow in the stratum corneum. The burrow can range from several millimeters to several centimeters in length. Eggs and faecal pellets laid down in the burrows then act as irritants which lead to itching. The larvae hatch after 50 to 72 hours and start to make new burrows. After maturation, they mate and the cycle is repeated every 10 to 17 days. The mites can survive for up to 2 months. Mode of transmission The mode of transmission is by means of direct skin-to-skin contact with infected individuals. Transfer from undergarments and bedclothes occurs rarely and only if these have been contaminated by infectious patients immediately beforehand. The mites can be spread rapidly between residents of the same house, nursing home or hospitals. A recent overseas epidemiological study shows that scabies tends to spread in homes and institutions where a high frequency of intimate personal contact or sharing of inanimate objects occurs.5 It confirms that fomite transmission is a major factor in household and nosocomial transmission of scabies. Clinical features

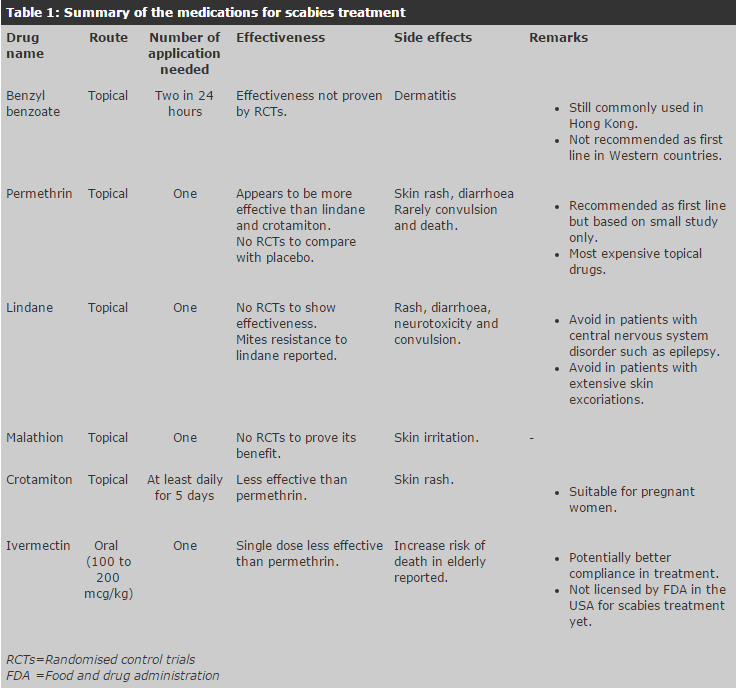

Pruritus may develop weeks after infestation of the mites when the older patients become allergic to the parasites. There are several clinical characteristics that help to identify scabies. First, generalized pruritus is present. The itchiness is felt even in areas with no apparent skin lesions while in many skin conditions such as eczema, the pruritus only occurs in the areas with skin lesions. The pruritus usually does not occur on the face except in neonates or in patients with Norwegian scabies. Another telltale symptom is that the itchiness is worse at night when the patient is warm in bed. Family physicians should know the classical distribution of the rash as shown in Figure 2. In brief, the common sites are the hands and fingers, anterior parts of the wrists, ankles, elbows, anterior axillary folds, buttocks, areas surrounding the nipples in females and external genitalia in males. Erythematous papules and nodules in the same areas are also seen. It has been described that the most common sites are in the hands and wrists while the scalp, face and neck are usually spared except in neonates or in patients suffering from Norwegian scabies. The morphology of the skin lesions can assist in making proper diagnosis. Primary lesions such as burrows are quite diagnostic. They are usually tunnels in the stratum corneum created by the mites and appear as grey or skin colour curved ridges ranging from a few millimeters to a few centimeters long. However, it is not surprising that burrows may not be found in many patients. One should not hesitate to diagnose scabies when other compatible clinical features are present except burrows. Vesicles are also primary lesions that are associated with scabies. The vesicles are isolated and filled with serous fluid. They tend to remain in discrete areas such as in the finger webs. Secondary lesions can result from infestation and scratching. All forms of eczematous reactions can occur including urticaria, eczematous papules and scratch marks. Bullous disease has been described to be associated with scabies. Pustules, impetigo, furuncles and cellulitis are features of secondary bacteria infection. The extent of the lesions varies among patients. This ranges from a few lesions in the form of itchy vesicles in the finger webs to truncal involvement with rash distribution as described above. The most severe one is Norwegian Scabies.6 This term was first used in 1848 to report a severe scabies infestation in patients with Hansen's disease. This condition is also called crusted scabies, as the lesions tend to involve hands and feet with crusting instead of the classical inflammatory papules and vesicles. Scales and thick crusts can be found all over the body. In this condition, the face and head may be involved with facial desquamation and shedding of the hair. Nail dystrophy is also a common feature in the fingers and toes. Pruritus varies from severe to absent. Compared with less severe cases of scabies in which the mites usually are confined to the stratum corneum and are few in number, those in Norwegian Scabies burrow deep into the epidermis and the number can be up to millions.7 It is believed that scratching helps to keep the mites down to a low number in patients suffering from non-Norwegian scabies. However, frail elderly patients suffering from stroke and dementia with poor awareness and upper limb function are at risk of developing Norwegian scabies because of their inability to scratch. Immunocompromised patients are particularly prone to develop Norwegian scabies as they cannot develop an allergic cutaneous reaction which leads to pruritus and scratching. It is useful to remember that scabies, like other diseases, may present atypically in the older population. It is especially so among those who are untreated for a long time. Family physicians should beware that the infestation can mimic various types of skin diseases such as eczema, bullous disease, and even erythroderma.3 Generalized lymphadenopathy may be present in some severe cases. Establishing diagnosis Scabies is suspected whenever there are burrows or when patients have typical symptoms with characteristic lesions and distribution. Identification of burrows can be made easier by touching the lesions with a dark fountain or felt tip pen. The ink will be absorbed into the burrow and highlight it as a dark line. Definite diagnosis of scabies requires the demonstration of mites, eggs, egg-casings or faeces in the burrows or vesicles. To obtain diagnostic materials, a commonly used method is to scrape with a surgical blade and transfer the material to a microscope slide for examination in mineral oil mounts or potassium hydroxide wet mount. Skin biopsy is rarely needed to establish the diagnosis. Practically, even in older patients with widespread excoriations, only few mites are present and they may be difficult, if not impossible, to find. Thus, treatment is often based on the clinical features.3 Although eosinophilia may be seen in the blood picture, it is not specific for scabies as it can occur in other dermatological conditions such as eczema. Treatment It is indeed surprising that scabies, having been known for centuries, is still a disease about which there is much uncertainty as far as treatment is concerned.8 First, it remains unclear which is the most effective topical treatment. Second, among the topical preparations available, how safe one is as compared to others remains a controversial issue. Finally, more study is needed to show the safety and efficacy of oral treatment with ivermectin as compared with the topical treatments. Topical preparations The topical preparations for scabies treatment include benzyl benzoate, crotamiton, lindane, malathion, and permethrin (Table 1). All the preparations are available in Hong Kong. Permethrin, lindane and malathion have the advantage of one application only in most cases. Benzyl benzoate needs to be applied twice in 24 hours. For crotamiton, it appears that five consecutive days of once daily application may be required to achieve an effective treatment.9

The usual recommendation is to apply the topical scabicide to the skin surface below the neck. The scabicide is allowed to dry and the same clothes can be worn. In the evening of the second day, a hot bath is taken and clean clothes should be worn. The traditional advice of taking a hot bath before application of the topical scabicide is considered obsolete as this may actually increase absorption of the drugs into the bloodstream. This leads to reduction in the effectiveness of the scabicide as it is removed from the skin quickly. In addition, this may increase the systemic toxicity of the scabicide. Occasionally, in older persons who are immuno-compromised, suffering from Norwegian Scabies or have treatment failure, application of the scabicides to scalp, neck, face and ears may be needed.10 The general principle is to avoid applying the topical preparations on mucous membrane. It is important to apply the scabicide to every part of the body, not just where the rash is. Judicious use of skin preparation is necessary to improve the success of topical treatment. Nails should be trimmed and thick crust loosened by keratolytic agents such as salicylic acid ointment or mechanically.6 In addition, repeat application of the preparations may be needed one week after the initial treatment in severe infestation. Benzyl benzoate This compound has been used for scabies treatment since 1931. It is still commonly used in Hong Kong. Previous clinical experience and case studies revealed that benzyl benzoate is a safe, cheap and effective scabicide for classic scabies. However, few randomised control trials (RCTs) have been performed to examine the efficacy of benzyl benzoate as compared to placebo.8 Benzyl benzoate has been replaced by permethrin and lindane in Western Countries as high treatment failure rate has been reported and it required two applications for each treatment.6,8 The compound is itself an irritant and repeated application may cause dermatitis.3,8 Permethrin Permethrin is a synthetic pyrethrin that requires only one application for treating scabies. It is the newest topical agent licensed to be used as scabies treatment in the USA (since 1985). Permethrin has been shown to be more effective than lindane and crotamiton.11-13 However, head to head comparison between permethrin and benzyl benzoate has not been performed. The safety profile of permethrin is good. Minor adverse effects such as rash and diarrhoea have been reported. Rarely, it may be associated with increase risk of convulsion and death.8 Permethrin has gained popularity recently and now is considered to be the first line treatment in many Western Countries.6,8 However, as commented in a recent review by the Cochrane Library, the choice is based on small-scale investigations and expert opinions.8 As mentioned above, rare but severe adverse side effects can happen and the cost is 10 times more than using benzyl benzoate.6,8,10 Lindane (gamma benzene hexachloride) Lindane has been used for scabies treatment since 1948. This preparation is available in Hong Kong as well as in the USA. However, it has been withdrawn from the UK market since 1996 because of commercial rather than toxicological reasons.8 In addition to minor reactions such as rash, papules and diarrhoea after lindane application, severe adverse effects such as aplastic anaemia and increased risk of neurotoxicity and convulsion have been reported.14-16 Hence, it is recommended to avoid its use on patients with central nervous system disorders including epilepsy and patients with extensive skin excoriations in whom significant systemic absorption of the drug may occur. One application is usually adequate for successful treatment. Mucous membranes are to be avoided. Taking a hot bath prior to the application of lindane is not recommended as this may increase the absorption of lindane resulting in increased neurotoxicity.8 Recently, it has been reported that some scabies mites have become resistant to lindane.17 Because of its risk of neurotoxicity and mite resistance, lindane has been replaced by permethrin as the standard treatment in many developed countries. Malathion Malathion has been used to treat scabies since mid 1970s. Similar to benzyl benzoate, no RCT investigating malathion has been done so far. However, non-controlled studies suggest that it is an effective treatment and is recommended in the UK for treatment of scabies.8 It may lead to irritation of skin but major side effect is rare. This preparation is commercially available in Hong Kong. Crotamiton Crotamiton has been shown to be an effective scabicide since late 1970s. It has been shown to be less effective than permethrin in a study conducted on children comparing single application of crotamiton with permethrin.12 Another study reveals that five consecutive days of single crotamiton application can achieve good efficacy as well as tolerability.9 Because of its possible lower efficacy and need to be applied continuously for a period of time, it is not recommended as a first line agent for scabies treatment. Nevertheless, it has been used in pregnant women and neonates with scabies as it appears to be less toxic. Oral treatment Ivermectin is the only oral drug for scabies treatment. It has not been licensed by the United States Food and Drug Administration for human scabies treatment and it is also not available in Hong Kong. It is given as a single oral dose of 100 to 200mcg/kg.18-21 The effectiveness of oral scabicide ivermectin as compared with other traditional topical preparations is controversial. One study performed in India demonstrates that ivermectin achieves a cure rate of 70% when a single dose is used, and up to 95% if ivermectin is given two doses at two weeks interval; whereas a single dose of permethrin can achieve a success rate of 97.8%. The paper concludes that a single application of permethrin is superior to a single dose of ivermectin.22 Other studies have not demonstrated any difference in efficacy between ivermectin and lindane or benzyl benzoate.21 Combination therapy of ivermectin and benzyl benzoate in severe Norwegian scabies has been explored and the authors conclude that combination therapy is more effective than single agent therapy.22 There has been concern about its safety especially in older persons as increased risk of death in a group of elderly patients with scabies in a long-term care facility has been reported.23 The causes of death among these older patients after treatment with ivermectin did not show any specific pattern. However, they tended to develop a sudden change in behaviour with lethargy, anorexia and listlessness prior to their death.23 The potential advantage of using ivermectin is that it is simpler to use as compared to the topical preparations and this can lead to better compliance in treatment.24 Therefore, more studies are warranted in future to reveal the cost-effectiveness and safety of the oral drug in human subjects. Persistent itchiness and rash Scabies infestation usually becomes non-infectious within a day after effective treatment has been given. However, itchiness and rash can persist for weeks to months.3 Family physicians should be aware of this and avoid unnecessary retreatment for it may lead to side effects such as contact dermatitis or even systemic toxicity in case of reapplication of lindane. Adjunctive treatment with antihistamines and calamine lotion can relieve pruritus. Judicious use of topical steroids helps to alleviate the itchiness that lingers on after scabicides. Scabies nodules can be very resistant and often a large dose of topical steroids is needed for treatment. Occasionally, antibiotics are needed if bacterial superinfection is present. Control of scabies outbreak As in most diseases, the principle of "prevention is better than cure" should be upheld in scabies management. In institutionalized settings, effective control of the epidemic is achieved by improvement in scabies recognition, awareness and prompt treatment of the disease. Staff rotation should be limited and the communication between infection control team and primary care workers should be strengthened. The success of scabies control depends on the co-operation of medical, nursing and allied health staff, health care workers as well as family members. Hand washing after personal contact is a simple and effective way of reducing cross-infestation. One way to limit the spread of scabies in the institution is to screen all the older residents for scabies on admission and on a regular basis afterwards. When an infested case is identified in the institution, vigorous screening for scabies is needed in all the older residents, staff and family members of the index case. If there is an outbreak, all the older residents, staff and family members of the index cases should receive prophylactic treatment for scabies. Conclusion Scabies is one of the few dermatological diseases that can be easily and effectively treated. Albeit not a life-threatening condition, it leads to much suffering for the patients both physically and psychologically. In addition, the management of the disease uses up valuable time of the nurses and health care workers. Family Physicians should maintain a high degree of suspicion and offer appropriate treatment without delay when necessary. Successful management and control of the disease in an institution requires a good scabies surveillance and treatment programme supported by efficient teamwork.

J K H Luk, MBBS(HK), MSc, MRCP(UK), FHKAM(Med)

F H W Chan, MBBCh(Wales), MSc(Derm.)(Wales), MRCP(Ireland), FHKAM(Med)

H H L Chan, FRCP(Glasg), FRCP (Edin), FHKCP, FHKAM(Med) Infection Control Nurse, Fung Yiu King Hospital.

Correspondence to: Dr J K H Luk, Senior Medical Officer, References

|

||||||