November 2002, Volume 24, No. 11 |

Discussion Paper

|

|

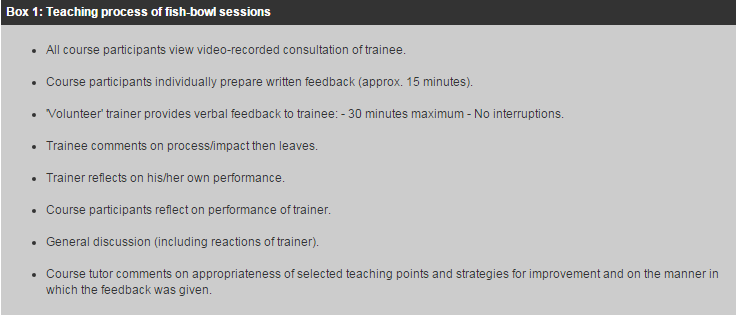

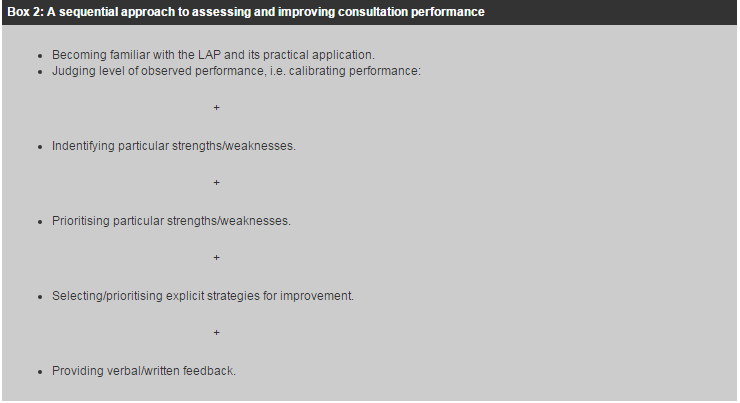

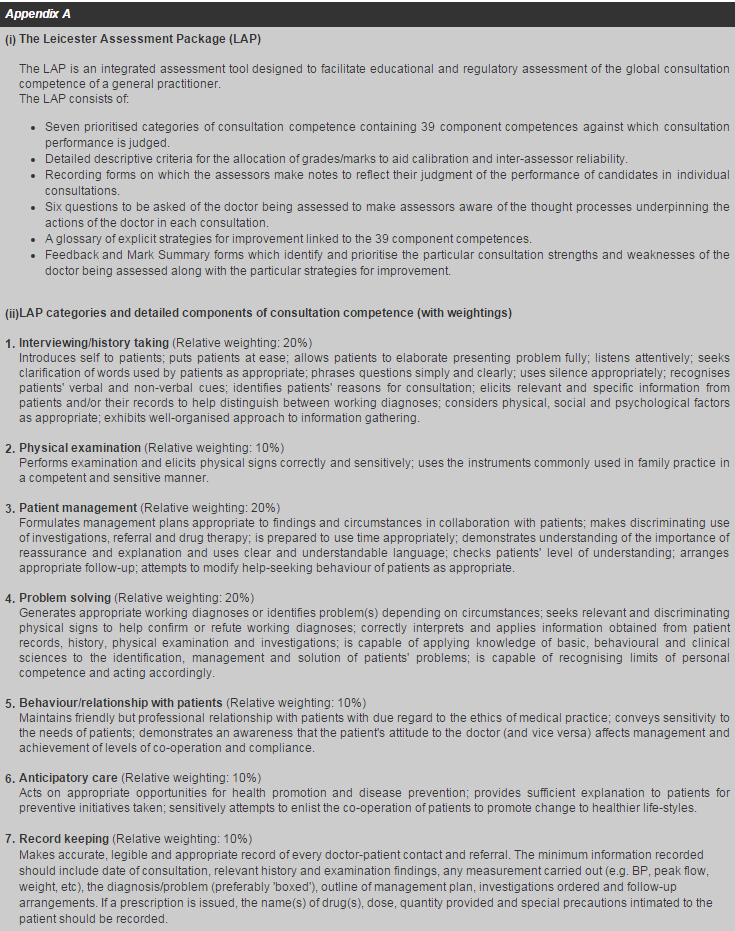

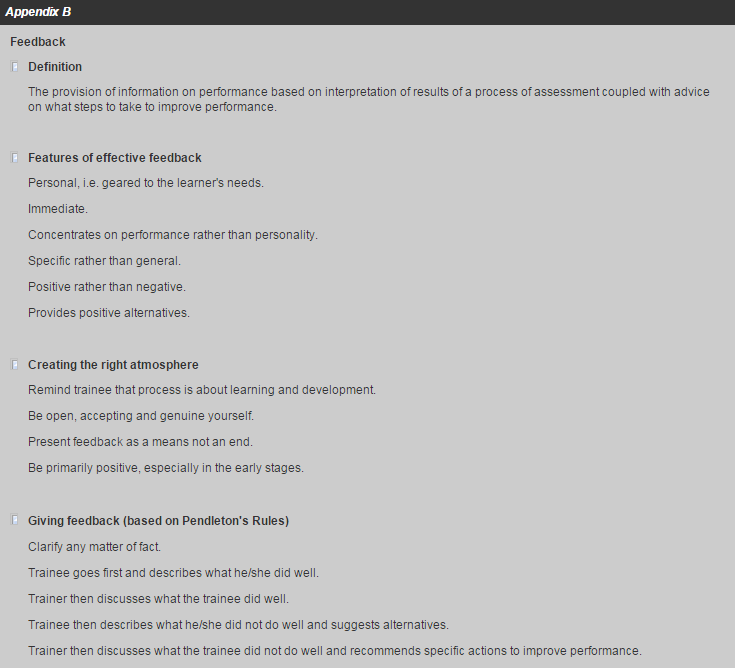

An introductory course on priority teaching methods for family medicine trainers in Hong KongR C Fraser, Y K Yiu 姚玉筠 HK Pract 2002;24:547-552 Summary Eleven family medicine trainers attended an experimental course to improve their ability to assess and enhance the consultation competence of trainees and to conduct problem and random case analyses. Participants were given opportunities for supervised practice in these techniques with individual feedback on performance using a fish-bowl approach. In the post-course questionnaire participants expressed highly favourable views about the content, relevance and participatory nature of the course and its impact on them, both as educators and clinicians. Participants indicated that even more opportunities for supervised practice should be provided in future courses. 摘要 十一位家庭醫生導師參加了一個實驗性課程。 目的是加強他們對學生診症評估、問題指導和隨機病例分析的能力。參加者在診症時接受觀察,然後聽取 針對其技巧和表現的意見。課程結束後問卷調查顯示,無論從教育者或臨床醫療工作者角度來看,參加 者對課程的內容、適切性和參予性均給予高度評價。參加者表示希望將來舉辦更多類似的課程。 Introduction In recent years, there has been a change in the role of the Hospital Authority in the training of family physicians.1 Starting from only 2 hospital based trainees in 1996, over 200 family medicine trainees are now under the hospital and community based training programme of the Hospital Authority. With the rapid increase in numbers of family medicine trainees in community based training, there is a relative shortage of trainers in the public sector. The Hospital Authority is collaborating with the private sector, Department of Health, the Universities and other non-government organisations to provide sufficient trainer capacity. As a result, there are great diversities of training methods between trainers of various parties which also results in a variation in the standards of training provided. In view of this, the Hospital Authority decided to hold an experimental workshop as the first step in equipping local family medicine trainers with the necessary skills which they could subsequently impart to others. For a variety of reasons, it was decided that the course would be held over four days of full-time participation. Because of the relatively short duration of the course it was decided to concentrate on teaching techniques which reflected the priority need of trainees, i.e. to develop clinical competence. This paper describes the course content and analyses the reactions of the participants to the course. Course aims The aims of the course were to enhance the ability of family medicine trainers in Hong Kong: 1. To assess the consultation performance of a family medicine trainee in a systematic manner. 2. To identify appropriate strategies to improve the clinical competence of individual family medicine trainees. 3. To conduct problem and random case analyses. Method The course was held in March 2002 with 11 participants and a single tutor (RCF). On the first morning some basic educational principles and concepts underpinning teaching and assessment in general, and the assessment and enhancement of consultation competence in particular, were highlighted and discussed. Participants were then introduced to the Leicester Assessment Package (LAP), (Appendix A) which has been demonstrated to be a valid2 and reliable3 instrument for assessing and improving4 consultation competence, and its use in practice was fully discussed. In the afternoon, participants used the LAP to make individual and independent assessments of the performance of a trainee doctor in a video-recorded consultation of that doctor with a simulated patient. The marks allocated by each course participant were displayed on a blackboard and differences in the marks awarded discussed to improve the reliability of scores allocated by participants when assessing consultations. On the second day this process was repeated with a different doctor, but participants were additionally required to identify and prioritise particular consulting strengths and weaknesses and to select explicit strategies for improvement. In the afternoon, participants were introduced to the principles and process of providing feedback (Appendix B), and then undertook a practical exercise in which one course member acted as the trainer assessing a video-recorded consultation of another course member playing the role of a trainee in a 'fish-bowl' situation. The teaching process as outlined in Box 1 was then implemented. Thus, a sequential approach was adopted in providing candidates with opportunities for supervised practice in assessing and improving consultation performance (see Box 2). The fourth day provided candidates with further opportunities for supervised practice, following the procedures outlined above, but on this occasion three actual trainees attended with their own video-recorded consultations. Thus the skills practised as separate entities were gradually integrated and four course participants were provided with an opportunity to practise/demonstrate their teaching skills and to receive feedback on their performance as trainers. The third day was devoted to problem case analysis. It began with an introduction to the principles and processes involved in conducting problem case analysis (PCA) and random case analysis (RCA). Four actual trainees sequentially presented problem cases to four course participants acting as trainer and the teaching process adopted, with suitable modifications, followed that outlined in Box 1.

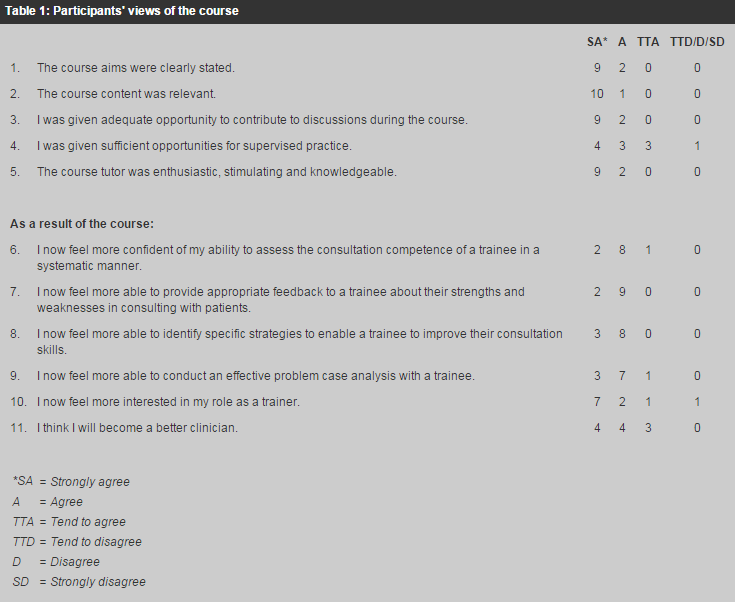

The evaluation of the course was principally based on the post course questionnaire in which participants were invited to respond to a series of eleven statements on a six-point scale, ranging from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree (see Table 1). Participants were also invited to make free text comments under four headings: What was liked/disliked most, How they had changed as a result of the course, Suggestions for improvement in this course in the future, Suggestions for inclusion of other topics in any future course.

Results The eleven participants consisted of eight males and three females. Seven had been qualified for 10-19 years and four for 20+ years. Five had been trainers for less than two years, three for 3-5 years and three for 6-10 years. None had previously undergone a systematic programme of preparation for teaching or assessing, although six had received some training in assessment and three in teaching. Eight participants were employed by the HA and three were private practitioners. There was a 100% response rate to the post-course questionnaire. The participants' views of the course are set out in Table 1 and are self-explanatory. Seventeen comments were made about what was liked most, covering nine different aspects, the most common of which, mentioned by three participants, was the active group participation. Of the twelve comments made about dislikes, there was no consensus, although 'insufficient handouts', 'disruption to private clinical practice', and 'very intensive' were each mentioned twice. Of the 22 comments made about how participants thought they had changed as a result of the course, five were 'more aware of their weaknesses' and six felt 'more aware of how to improve their weaknesses'. A further four mentioned that they were 'more aware of the LAP as a powerful tool to facilitate the improvement of consultation skills'. Regarding future improvements, six participants mentioned the need to provide 'more opportunities/time to practise under supervision' and two suggested the course be 'arranged for weekends to limit disruption to private practice'. Only two additional topics were suggested. Discussion The authors understand that this was the first such course to be held in Hong Kong and, consequently, important pointers for the future can be learned from it. The differential range of responses to individual questions in the questionnaire and the frequency and nature of free text comments suggest that participants were making considered rather than mechanistic responses. Since respondents were not required to identify themselves, the views expressed in the questionnaire can reasonably be assumed to reflect the true opinions of participants. It is gratifying that participants expressed highly favourable views about the content, relevance and participatory nature of the course and its impact on them, both as educators and clinicians. Although the participants were already experienced clinically, eight of them strongly agreed or agreed that they would be better clinicians as a direct consequence of the course. This replicates the views of previous participants on similar courses.5 On the other hand, most participants had had little or no systematic preparation for their training role and five had been trainers for less than two years. In the practical course sessions it was evident - even to the participants themselves - that there is a substantial difference between knowing how to perform a task (for example analysis of consultation performance, conducting a PCA) and actually carrying it out,6 and that the observation of actual practice is the most effective way to make a judgement of someone's competence, either as a clinician or educator.7 Although the participants acknowledged that opportunities for supervised practice using the fish-bowl technique made them more aware of their weaknesses in assessing and providing feedback on consultation performance and in conducting PCAs, the feedback they received also made them more aware of ways of improving their weaknesses. Nevertheless, the biggest criticism of the course was that it offered insufficient opportunities for supervised practice and this was the issue which participants felt needed to be remedied in future courses. Although the course content was sharply focussed, the duration of the course was relatively short and the tutor: participant ratio was unfavourable. Only eight of the eleven participants were given a single opportunity to develop their skills. Ideally, the maximum number of participants per tutor should be 6-8 and the course duration should be sufficient to accommodate repeated opportunities for practice under supervision for all participants. It must be acknowledged, however, that this is expensive in terms of logistics and human resources and compromises have to be made. Nevertheless, participants felt that their teaching skills had improved as a result of attendance at the course and it was particularly gratifying that almost all participants had increased motivation for their training role. It was recognised, however, that trainers who were also private practitioners had particular difficulties in attending courses on a full-time basis because of their clinical responsibilities. Conclusion This experimental introductory course on priority teaching methods for family medicine trainers in Hong Kong evoked a highly favourable response from participants. As a direct result of attendance at the course, almost all participants felt more confident of their ability to assess the consultation competence of trainees in a systematic manner, to prioritise strengths and weaknesses, to provide trainees with appropriate feedback on specific strategies to improve their consultation skills and in conducting problem case analysis. Participants also became more interested in their role as trainers. The principal criticism of the course was that it provided inadequate opportunities for practice under supervision and this issue needs to be addressed in future courses. Acknowledgment: We wish to thank Dr Aylwin Chan, Executive Manager, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong for his assistance in the organisation of the course and the course participants for completing the questionnaires.

R C Fraser, CBE, MD, FRCGP, FHKCFP Senior Medical Officer,Caritas Medical Centre. Correspondence to: Professor R C Fraser , Department of General Practice & Primary Health Care, University of Leicester, Leicester General Hospital, Gwendolen Road, Leicester LE5 4PW, UK. References

|

||