|

August 2002, Volume 24, No. 8

|

Update Article

|

|||||||

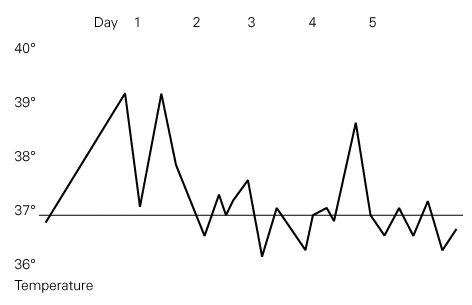

Dengue feverN Y Chan 陳迺賢,D V K Chao 周偉強 HK Pract 2002;24:395-400 Summary Fever in a traveller returning from a tropical region is a difficult issue to manage. Dengue virus infection is one of the most important endemic diseases in tropical regions. This article reviews the aetiology, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment and prevention of the disease. 摘要 治療從熱帶旅行回港旅客發熱的情況是困難的。登革熱(登革熱病毒感染)是熱帶地區最常見的流行病之一。本文回顧此病的成因、流行病學、診斷、治療及預防。 Introduction International air travel is more convenient and faster than decades before and gives rise to an increasing number of travellers worldwide. This also speeds up the transmission of infectious diseases from country to country, causing outbreaks in non-endemic regions. Doctors in the non-endemic areas may have difficulty appreciating the significance of non-specific symptoms, particularly if they are unfamiliar with the imported diseases.1 Dengue fever is one of the most important tropical diseases. The clinical manifestation is illustrated by the following case. Case history A 25 years old Canadian lady complained of fever and systemic upset for four days. She enjoyed good past health and was a non-smoker, and a social drinker. She was single, but sexually active. There was no known history of allergy. She lived in New York and came to Hong Kong as one of the destinations on her trip to South East Asia. Before arrival in Hong Kong, she had visited Malaysia, Tokyo, Vietnam, Thailand and Singapore. At each place she had stayed for a few days, mainly in hostels. She had received vaccination for Hepatitis A, Typhoid, Poliomyelitis, and Tetanus before starting her tour. She remembered experiencing mosquito bites only in Singapore. She presented to the Accident and Emergency Department on arrival in Hong Kong and was admitted to hospital for further work up. She had become symptomatic in Singapore with fever for four days, chills, rigors, tiredness, headache and severe muscle pain. Her appetite was poor and she had nausea, but no vomiting, nor any abdominal pain. She did not have any respiratory, nor urinary symptoms. She did not complain of any rash. Her menstrual flow was not excessive. She used pads, not tampons. There was not any abnormal vaginal discharge and she did not have any sexual exposure recently. Physical examination revealed that she was febrile and tired looking. She was haemodynamically stable. Her blood pressure was 107/69 mmHg on admission, with a pulse rate of 80 beats per minute. A small number of petechiae were noted on both lower limbs, otherwise there was no rash. She was not pale, nor cyanotic. There was no lymphadenopathy. Urine dipstick tests for albumin, sugar, red blood cell were all negative. Cardiovascular examination revealed that there was no sign of heart failure. Chest was clear. Examinations of abdomen and central nervous system were unremarkable. Investigation results showed leucopenia (WBC = 2.5 X 109/L, neutrophils = 2.0 X 109/L, lymphocyte = 0.3 X 109/L) and thrombocytopenia (PLT = 90 X 109/L). Haemoglobin level was normal (Hb = 13.2 g/dL). Clotting profile was slightly deranged with INR = 1.1. Renal function test was normal. There was mild elevation of AST (82 IU/L) initially, otherwise liver function tests were normal. Marked elevation of creatine kinase (1058 IU/L) and LDH (560 IU/L) were noted. Her electrocardiogram was normal. Chest xray showed that the lung fields were clear. Clinical sepsis was suspected, thus a course of intravenous ciprofloxacin was given after sepsis work up had been performed. The plan was to look for clinical progress and wait for investigation results. Progress For a few days after admission, her condition remained unchanged. Her appetite was poor, but she was able to feed herself. She was well hydrated and there was no need for intravenous fluid replacement. She was nauseated and tired looking. Fever seemed to have subsided initially, but a flick of fever reappeared on day 4 of admission (Figure 1). She was haemodynamically stable. There was no sign of fluid retention. The extent of petechiae remained the same. However, a generalised macular rash developed on the face, trunk and limbs soon after admission. The oral mucosa was not affected.

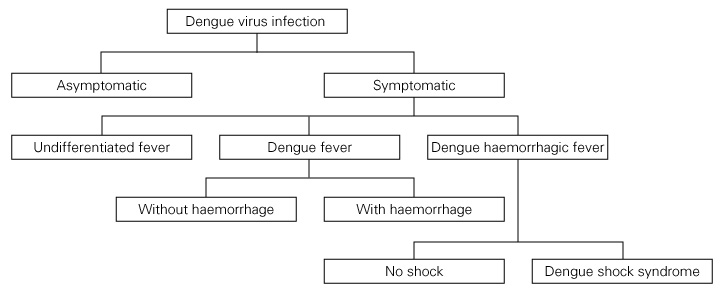

The creatine kinase level gradually returned to normal. Renal function test was normal all along. Haematological results showed that leucopenia persisted. However, the white cell counts dropped to 2.2 109/L, then rose to 2.7 109/L. Platelet count dropped to 28 109/L, but then increased back to 70 109/L. Haemoglobin level and haematocrit remained normal. The clotting profile returned to normal on day 4. The liver functions were further impaired. ALT and AST levels rose to around ten times of normal values, but plasma bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels remained normal. On the fourth day of admission, other investigation results were available. Rheumatoid factor was negative. Anti-nuclear antibody was 1:320 (homogenous, speckled), but anti-ds DNA antibody and ESR were within normal limit. Blood, mid-stream urine and sputum culture results were negative. Peripheral blood smear for malaria was screened, which was also negative. Monospot, ASOT, Widal titre, Weil-Felix titre and Brucella titre were all unremarkable. Hepatitis serology tests including HBsAg, anti-HAV, IgM antibody, anti-HCV antibody were all negative. Screening for HIV was also done, which was negative. Other viral titres including rubella, toxoplasma, influenza, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus, cytomegalovirus, mycoplasma, chlamydia, and even hantavirus were all unremarkable. Finally, on the fifth day, it was found that Dengue virus IgM antibody was positive, with IgG antibody negative. The diagnosis of Dengue fever was finally made. The patient was then transferred to a local infectious disease unit. Her condition gradually improved. She was then discharged from hospital and was able to return to her own country one week later. Dengue fever Dengue virus infection is a viral infection transmitted by mosquito. Dengue virus belongs to the family of Flaviviruses. It is a single stranded RNA virus. There are four serotypes, namely dengue virus 1, 2, 3 and 4. Infection in human by one serotype produces life long immunity to the same serotype, but only temporary and partial protection to other serotypes. The host is human and the vectors are Aedes mosquitoes. Once the Aedes mosquito bites an infected human, it remains infectious for life. Transmission to human is by the bite of infected Aedes mosquito. However, the virus will disappear from the blood of a human two to seven days after infection. Aedes aegypti is the principal vector for dengue virus infection. It is closely associated to the human habitation and it is day-biting, with most biting activity during the early morning and late afternoon. Other Aedes species, such as Aedes albopictus and Aedes polynesiensis also caused dengue outbreaks in some regions.2,3 Epidemiology It is estimated that there are 100 million cases of dengue virus infection worldwide annually.4 It is endemic in most tropical and subtropical areas, especially South East Asia. It has also caused outbreaks in the tropical regions of Africa, Central and South America, Western Pacific and Eastern Mediterranean.2 Hong Kong is not an endemic region for dengue virus infection, but there are a few cases reported every year. In 1997, there were 10 cases of dengue fever reported.5 In 1998 and 1999, 15 and 5 cases were reported respectively.6,7 All cases were imported. Although Aedes aegypti was not found in Hong Kong, Aedes albopictus is present. It means that local transmission of dengue fever is possible. Moreover, there were more than 1000 cases of locally transmitted dengue fever in Macau in 2001. Clinical manifestations The incubation period of dengue virus infection is four to seven days. The clinical presentations are variable. It may be asymptomatic, or just an undifferentiated febrile illness. It may also lead to classical dengue fever, dengue haemorrhagic fever, or dengue shock syndrome.2,3 (Figure 2)

Dengue fever is a febrile illness of acute onset, characterised by severe headache, retro-ocular pain, severe muscle and bone pain (so-called "break-bone fever"), nausea, vomiting and rash. The fever pattern may be a "saddleback" curve. A maculopapular rash may appear on the third or fourth day. Petechiae may present. Leucopenia and thrombocytopenia are frequent. Serum liver enzymes may be moderately raised. Sometimes, it may be associated with haemorrhagic complications such as epistaxis, gingival bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding, haematuria, and menorrhagia. Mortality may be related to severe bleeding, but it is rare. Prognosis is good. Differential diagnoses include chikungunya, measles, leptospirosis, typhoid, malaria and other viral diseases. However, an exact diagnosis cannot rely entirely on the clinical presentations. WHO defines dengue fever by clinical manifestations, together with a supportive serology.2-4 Dengue haemorrhagic fever is defined as a febrile illness with thrombocytopenia (100 109/L), evidence of plasma leakage, and bleeding tendencies evidenced by a positive tourniquet test, presence of skin haemorrhages, or other major bleeding. Plasma leakage is manifested by a rise of haematocrit by at least 20%, a drop by 20% after volume replacement treatment, or signs of pleural effusion, ascities and hypoproteinaemia. It is the presence of plasma leakage caused by increased vascular permeability that differentiates dengue haemorrhagic fever from classical dengue fever. Sometimes, it is associated with hepatomegaly.2-4 The differential diagnoses may include other viral haemorrhagic fevers, such as Lassa, Marbury, Ebola, Hantavirus, yellow fever.8 Dengue shock syndrome is defined as dengue haemorrhagic fever with evidence of circulatory failure, including rapid and weak pulse, and narrow pulse pressure or the presence of hypotension. The mortality from dengue haemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome varies between outbreaks and depends on available supportive care. It may be as high as 50%.2-4,9 The pathogenesis of dengue haemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome is not clear. One hypothesis is the phenomenon of antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE), which suggests that heterotypic antibodies from previous dengue virus infection promotes viral replication within mononuclear leucocytes. Another major hypothesis is that a more virulent biotype replicates to higher titres and causes more severe manifestations.4,10 Laboratory diagnosis To establish a laboratory diagnosis of dengue virus infection, either a serological method or viral culture can be used. Serological diagnosis depends on the IgM or IgG antibodies. The presence of IgM antibody in a single acute phase sample or a rise in IgG antibody titre detected by haemagglutination inhibition test in paired sera can confirm the diagnosis. In early disease, isolation of dengue virus by culture can give rise to definitive diagnosis. The reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification assay for detection of dengue RNA is another option for laboratory diagnosis.2,3 Treatment The management for dengue fever is entirely supportive. Bed rest, control of fever, pain relief and adequate fluid intake may be useful. Avoid the use of aspirin because it can increase bleeding tendency, and may be associated with Reye's syndrome in a paediatric patient. In dengue haemorrhagic fever with or without shock, the most important task is to correct plasma loss and improve circulation by adequate fluid replacement, either orally or intravenously. Electrolyte disturbance should be corrected. In a case with severe bleeding tendency, the use of blood products may be helpful. In any stage of the disease, frequent monitoring of fluid balance, haemodynamic status including blood pressure and pulse rate, platelet count, haematocrit, clotting profile, serum electrolyte, liver function tests and haemorrhagic manifestations are mandatory.2-4 Prevention Currently, there is no vaccine against dengue virus infection. To control the disease, vector control plays an important role. It can be achieved by improvement of water supply and storage, effective solid waste management and use of insecticide. Disease surveillance aims at early detection of outbreaks. This includes monitoring of suspected cases of dengue virus infection, case reporting and epidemiological investigations. This is extremely important in endemic areas. It is important for travellers going to a tropical region or a region where dengue virus infection is endemic to avoid insect bites. They should wear clothes that reduce the amount of exposed skin. Use of insecticide and insect repellent will also play an important role. They should avoid travelling to regions with current outbreaks of dengue virus infection.2-4 Discussion This case illustrates a classical presentation of dengue fever. However, it may be difficult to define where the patient became infected. She had visited Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand and Singapore before coming to Hong Kong. All these South East Asian countries are endemic regions for dengue fever or dengue haemorrhagic fever.2 Although vaccine for dengue virus infection is not yet available, live attenuated vaccines have been tested in phase I and II trials in Thailand.4 Vector control is still the main measure for disease control. Recently, a 3-year programme using the mesocyclops crustacean, which devours the larvae of the Aedes mosquito has been successful in reducing the risk of dengue virus infection in Vietnam.11 Conclusion Dengue fever is not commonly seen in our locality, so it may not be easy for local doctors to make a correct diagnosis at the early stage. However, a large number of Hong Kong residents have travelled to other countries, including our neighbour countries in South East Asia. It would be helpful if local doctors can acquire more knowledge and skills in managing the different imported diseases. Thus, a correct diagnosis can be made promptly and treatment can be started earlier. A detailed travel history is always helpful.

N Y Chan, MBChB(CUHK) Family Medicine Cluster Coordinator (KE), Department of Family Medicine, United Christian Hospital. Correspondence to: Dr N Y Chan, HA Staff Clinic, Department of Family Medicine, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Kowloon, Hong Kong. References

|

||||||||