|

September 2001, Volume 23, No. 9

|

Update Articles

|

The interesting but confusing phenomenon of neurasthenia and chronic fatigue syndromeK Y Mak 麥基恩 HK Pract 2001;23:390-396 Summary The term 'neurasthenia' is rather confusing, particularly for the Chinese. It has undergone metamorphosis, and is nowadays characterised by unexplained persistent physical symptoms especially chronic fatigue. It is a common presentation to primary care doctors, and these patients are frequent consumers of health care services of various types. There is a high association with psychological distress and other psychiatric disorders have to be ruled out in order to reduce confusion. Treatment is rather non-specific, though antidepressants and/or cognitive-behavioural therapy can be quite effective. The author recommends that the term 'eurasthenia' be used as a layman term while communicating with the patient, but to use 'chronic fatigue syndrome' as a medical terminology when corresponding with other colleagues. 摘要 神經衰弱的定義含糊,而且不斷改變,現在多用 以形容持續性的,難以解釋的軀體症狀,特別是慢性 疲勞。病人常四處求醫,基層醫生也常接觸到這類病 人。本病症與心理壓力有密切關係,診斷時也需排除 其他精神疾病。現在尚無特殊治療法,抗憂鬱藥和認 知療法均頗為有效。作者建議可以繼續使用神經衰弱 的名稱與病人溝通解釋,但改用' 慢性疲勞綜合症' 作 為專用醫學名詞。 Introduction and history The term 'neurasthenia' has meant different things in different places to different people. Literally, the word means 'nerves exhaustion', thus conveying some physical problems with the body. Brown, a pupil of Cullen, developed the concept of neurasthenia at the end of the 18th century to describe general functional disorders of the nervous system with no specific localised lesions found. Kraus in 1831 and Most in 1836 equated neurasthenia as a synonym for nervous weakness, and von Deusen wrote about the topic some 30 years later.1 However, it was George M Beard who in 1867 described more than 50 symptoms, both physical and mental, that can be diagnosed as neurasthenia. The main feature is that of unexplained chronic 'fatigue' and weakness.2 According to him, the disorder was the exhaustion of the nervous force caused by environmental factors and rapid social changes in society such as the telegraph, the railroads, political and religious liberty, etc. In France, Charcot reclassified the symptoms and expanded the concept further to become the second 'great neuroses' besides hysteria. Gradually, this concept declined in popularity because its symptomatology was too vast and protean, and the hypothesis of 'nervous weakness' was unverifiable. It was replaced by the new psychopathological concept of anxiety (developed by Freud who associated it with sexuality and Janet who replaced it with the term 'psychasthenia' to mean psychological tension) and also depression (expounded by Kraepelin into psychogenic depression). The concept of neurasthenia was however maintained in Russia, with Pavlov dividing neuroses into hysteria and neurasthenia, with the latter further subdivided into the hypersthenic form (irritable) and hyposthenic form (depression). In Japan, Morita published his work on neurasthenia (or 'shinkeishitu') and it was regarded as a 'culture-specific' syndrome, he even proposed a specific psychotherapy still in use today.3 As many doctors in China were trained in the USSR after the communist takeover, the term 'neurasthenia' (or 'shen-jin-shui-rue') remained a popular diagnosis in China for the past few decades. Arthur Kleinman4 studied a population of patients thus diagnosed in China, and found that many were actually suffering from 'anxiety disorder' and/or 'depressive disorder'. In a way, the Chinese patients (especially the elderly) are more willing to accept medical treatment for the label of 'neurasthenia', compared to the more specific diagnosis of 'depressive disorder', 'anxiety disorder' or 'somatisation disorder'. In order to avoid confusion and to improve compliance in treatment, the present author recommends that clinicians could perhaps still maintain the layman term 'neurasthenia' when giving a diagnosis acceptable to their patients. However, they should perhaps use the term 'chronic fatigue syndrome' when discussing the disorder in a professional manner. In a way, the sense of organicity felt by many patients suffering from the disorder does merit some consideration. It has been known for a long time that fatigue often occurs after an infection, either a viral or a bacteria infection. Infectious mononucleosis and brucellosis are famous examples. In recent years, chronic fatigue syndrome has been associated with the so-called ME syndrome (myalgic encephalomyelitis, also called 'post-viral fatigue'). In a way, ME implies an infection involving the neurological system, and viruses such as the Coxsackie B, the human herpes virus and the Epstein-Barr virus have been implicated. However, evidence of previous infection by the above viruses are commonly found even in normal persons. This has already given to some confusion in the diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome. Ayres et al5 found exposure to Coxiella burnetii (Q fever) is related to the later manifestation of chronic fatigue. Using magnetic resonance imaging on patients with severe post-poliomyelitis fatigue, Bruno et al6 found small discrete punctuate areas of hyperintense signal in the reticular formation, putamen, medial lemniscus and white matter tracts. Together with the Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) findings of reduced cortical blood flow in the brain stem,7 Dickinson8 hypothesized that chronic fatigue syndrome is secondary to damages of the ascending reticular activating system at the brain stem. Nevertheless, in many other fatigue patients, no physical or laboratory abnormalities are found. Other biological causes such as muscle dysfunction (including myofibrils abnormalities), brain pathologies and immunoglobulin deficiencies have also been proposed; but again definitive laboratory findings are still lacking.9 Prevalence Fatigue is a common presenting symptom to primary care doctors, and about three-quarters of the patients experience persistent fatigue.10 Kroenke et al11 found that about a quarter of the adult patients attending primary care clinics complainted of chronic fatigue and weakness. Hall et al12 found a highly significant increase in illness reporting before developing the chronic fatigue syndrome. The group's recent study found a more frequent consultation illness behaviour (for a variety of problems) for 15 years even before developing the syndrome, compared to the control groups.13 The risk of chronicity increases when there is concurrent psychological distress, either in the past or in the present.10 According to papers published,14,15 as many as 60-80% of all psychiatric outpatients in China are diagnosed as suffering from this disorder. The diagnosis is less common in children and adolescents.16 In Switzerland, the one-year prevalent rate was estimated to be 5% for men and 10% for women. It was also found that no less than 79% of diagnosed patients had concurrent or successive diagnoses of depression or anxiety disorder.17 Hagnell18 in his 25-year study, found that the frequency of fatigue was higher in women than in men during the period 1947-1956, but the frequency among men increased and became equal during 1957-1972. Clinical features Because of the confusion in diagnosis, different authorities have different clusters of symptoms for neurasthenia, and the diagnostic features have changed over the years. For example, Beard19 divided his 50 symptoms into 'mental symptoms' e.g. psychic fatiguability, inability to concentrate, etc. and 'bodily or physical exhaustion' e.g. pains, muscular tension, etc. He even divided the symptoms into eight different groups. Using cluster analysis, the Zurich group17 regrouped the symptoms into three clusters:

Various attempts had been made to classify neurasthenia. Because of its widespread use and the continuing existence of syndromes that do not seem to be assignable to any of the other conditions,20 the term 'neurasthenia' remains in the ICD-10. But in the DSM-IV classification, there is no such specific diagnosis, unexplained physical symptoms such as fatigue or body weakness of less than 6 months' duration that are not due to another mental disorder is classified under the category of 'somatoform disorder not otherwise specified'. But according to the ICD-10, there are two conditions, either

At least one of the following symptoms must be present in order to diagnose neurasthenia: feelings of muscular aches and pains, dizziness, tension headaches, sleep disturbance, inability to relax and irritability. Note that these symptoms are very common and non-specific (they can occur in many other psychiatric disorders), and are thus of not much diagnostic value. One condition for the diagnosis is that the patient is unable to recover by means of rest, relaxation or entertainment. As mentioned above, the diagnosis made by Chinese doctors is quite non-specific and often is a mixture of somatic, anxiety and depressive symptoms.4 So far, there is no published scientific report known to the author as regard the presenting features of Chinese patients suffering from the pure 'chronic fatigue syndrome'. Differential diagnosis (and/or comorbidity) From the above discussion it is obvious that the cardinal symptoms of neurasthenia are frequently seen in patients with other clinical diagnoses, especially:

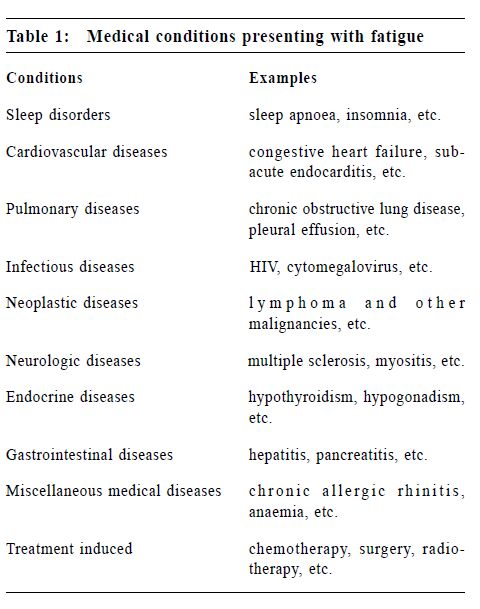

In a survey in Shanghai, China by Zhang,21 the most frequent comorbid diagnosis in neurasthenic patients using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule was depression (67.5%), generalised anxiety disorder (50%) and somatoform disorder (62.5%). Each patient has an average of 2.6 syndromes. Whether these should be considered as comorbidities or whether they should replace 'neurasthenia' altogether is still rather controversial. Quite often, neurasthenia is associated with the premenstrual syndrome and the post-menopausal syndrome, but further studies are needed to establish the link. Shift work that would disturb the sleep/wake cycle is also a precipitator, and sleep apnoea can induce daytime sleepiness. It should be noted that certain medications (especially tranquillizers and antihistamines), opioids and alcohol, and even certain environmental toxins can cause neurasthenia-like symptoms. Withdrawal from stimulants and narcotic intoxication can also induce severe fatigue. Management Assessment Concerning chronic fatigue in particular, the Fatigue Questionnaire22 and the Fatigue Severity Scale23 can be quite helpful. It is useful to exclude Somatisation Disorders, Anxiety Disorders or Depressive Disorders clinically, and Stress Related Disorders should also be ruled out. Physical causes including medications and substance abuse have to be ruled out (Table 1).

For patients presenting with a prolonged and incapacitating state of fatigue, a complete physical examination and laboratory investigations are necessary to rule out genuine organic disorders. If there was a previous episode of acute infection, it is justified to do the following tests:

Treatment In the earliest days, Beard24 recommended aggressive medical and electrical treatment for neurasthenia. It was the American neurologist Silas Weir Mitchell who in 1871 proposed the 'rest cure'. In Japan, the Morita therapy requiring prolonged bed-rest was designed to treat such a condition.3 However, this measure (if successful) is an exclusion criterion in the ICD-10 diagnosis. Nevertheless, a healthy lifestyle with a balanced diet (especially in the elderly), initial rest followed by gradual increase in exercise capacity, and a graded resumption of everyday recreation are often recommended. Despite a lack of understanding of aetiology, chronic fatigue syndrome can still be treated. Time and attention paid to the patients are sometimes therapeutic, relaxation techniques can be taught. Any underlying or coexisting physical disease or psychiatric disorder should be treated accordingly. Some antidepressants, especially bupropion and reboxetine which have some stimulating properties, have been tried with varying success. Salbutamine, a specific cholinergic agent (acting on the muscarinic receptors of the nervous system) has been found useful in hastening recovery of patients with post-infection fatigue.25 Psycho-stimulants such as methylphenidate and other amphetamine derivatives, have been tried but there is the adverse problem of substance abuse. Modafinal, a newer type of stimulant which acts on the dopamine and noradrenaline systems, has recently been used with some success. On the psychotherapy side, cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) for the chronic fatigue syndrome appears more effective than the usual medical care or relaxation,26,27 CBT consisted of 'a treatment rationale, activity planning, homework, establishing a sleep routine and other cognitive interventions'. The counseling skills in this study consisted of a non-directive and clientcentred approach, allowing the patients to talk through their concerns and difficulties, with the aim to 'understand themselves better, to suggest alternative understandings, to uncover the links between current distress and past experience, and to provide the conditions for growth and healing'. Other treatment strategies have been developed according to the viewpoints whether it is organic (like the ME syndrome) or psychogenic. For the latter, treatment varies according to its inclusiveness or exclusiveness of other 'minor psychiatric disorders'. In a way, it is not easy to refer such patients to a psychiatrist as many would regard the disorder as organic in origin. Sometimes, referral is possible only after the patients have exhausted the list of non-psychiatrist physicians and have undergone extensive investigations to no avail. Prognosis For treated patients, the probability of relapse is quite high.17 As mentioned, fatigue syndromes if untreated will run a chronic course, and can be quite costly to the health care providers. In Australia, the overall economic cost for chronic fatigue syndrome was estimated to be Australian $9429 per patient due mainly to the loss of employment.28 In fact, such chronic disorder is highly correlated to unemployment and consumption of various types of health services.29 Conclusion In a way, 'neurasthenia' is perhaps the name given to a set of symptoms that are non-specific reactions to subacute irritation of the central nervous system. According to Sartorius20 who called it a 'disease of modernisation', there are still a few unanswered questions:

Nobody knows whether this term 'neurasthenia' may one day, like 'hysteria', disappear from the clinical diagnosis in psychiatry. On the other hand, some would like to revive this term for some specific syndromes. Meanwhile, in order to avoid confusion, it is better to follow the trend of replacing 'neurasthenia' by a more specific term such as 'chronic fatigue syndrome or disorder'. Key messages

K Y Mak, MBBS, MD, DPM, FRCPsych

Clinical Associate Professor (Part-time), Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong. Correspondence to : Dr K Y Mak, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong.

References

|

|