|

May 2001, Volume 23, No. 5

|

Original Article

|

Evidence-based management of dyslipidaemia: Hong Kong family physicians' perspectiveY T Wun 溫煜讚, J L Tang 唐金陵, D V K Chao 周偉強 HK Pract 2001;23:191-200 Summary

Objective: To survey the knowledge of and practice by local family

physicians in evidence-based management of dyslipidaemia.

Keywords: Family physicians, lipid, cholesterol, guidelines, management 摘要

目的: 調查本地家庭醫生關於異常血脂症的知識和用 科學證據支持的治療方案。

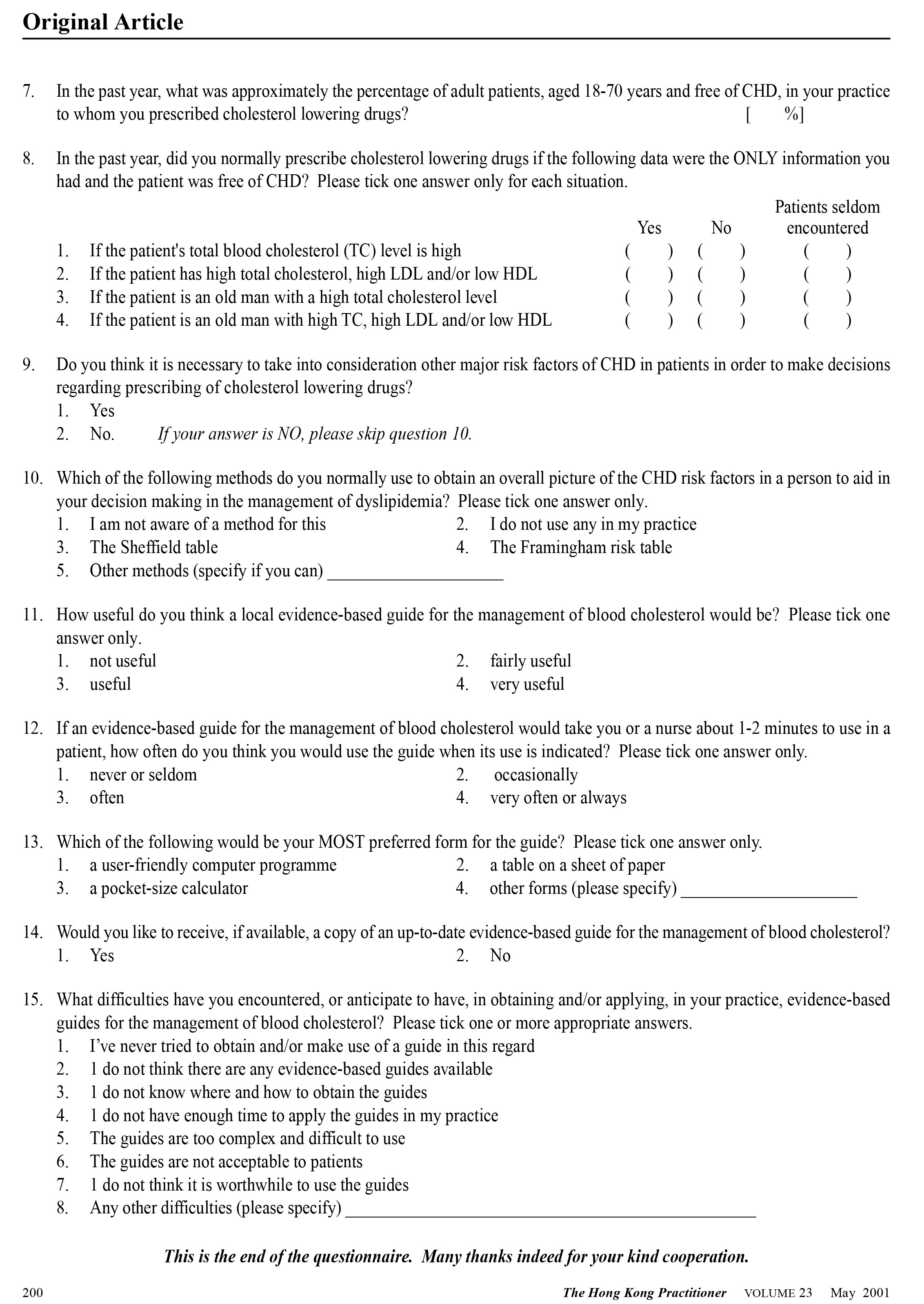

Introduction Coronary heart disease (CHD) is the second leading cause of deaths in Hong Kong accounting for about 10% of the total mortality.1 Dyslipidaemia is a major risk factor for CHD and lowering the blood cholesterol reduces the morbidity and mortality of CHD.2 As the treatment of blood cholesterol for primary prevention is mostly managed by family physicians, their knowledge and practice regarding evidence-based management of dyslipidaemia are important for the prevention of CHD in the general population. The understanding of the relationship between blood cholesterol and CHD, and of the indication for lowering the cholesterol for primary prevention of CHD has been evolving. Early efforts were primarily focused on total cholesterol: the higher the total cholesterol, the greater the risk of CHD.3,4 Those with elevated total cholesterol were given active treatment. Later studies found that the components of a person's cholesterol, rather than the total cholesterol, were better predictors for the risk of CHD: people with high Low Density Lipoproteins (LDL) and low High Density Lipoproteins (HDL) were at a high risk of CHD and thus given treatment for primary prevention.5,6 More recent studies showed an interaction among the major risk factors of CHD: those with a poor lipid profile carry a greater risk only in the presence of other risk factors. Evidence from randomised controlled trials also revealed that the benefit of lowering cholesterol was largely determined by the risk factors a person has rather than blood cholesterol alone.2,7,8 Nowadays, it is generally believed that moderately elevated blood cholesterol may need to be lowered with drugs if the person has a high projected future risk of CHD based on all his/her major risk factors. Conversely, a person with high blood cholesterol, except familial hyperlipidaemia, may not need drug treatment if his/her overall risk is relatively low. Based on this new concept, several management guidelines have been developed for dyslipidaemia since 1993.9-12 The starting point in the management of blood lipids for primary prevention is thus an assessment of the patient's overall risk profile. Our survey examined the knowledge and the practice of local family physicians against the current evidence-based guidelines in the management of dyslipidaemia. We also wanted to determine the obstacles and difficulties family physicians may encounter in practising evidence-based management of dyslipidaemia and their attitudes on the need for a set of local guidelines. Participants and methods A 15-item questionnaire was sent by post in March 2000 to all members of the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians (126 Fellows, 246 Full Members, and 913 Associate Members), with self-addressed return envelopes. Due to limited funding, no reminder was sent for enhancing the response rate. The questionnaire (Appendix) covered three aspects. The first part dealt with the respondent's professional profile. The second part focused on family physicians' knowledge and practice of evidence-based management of dyslipidaemia. Answers to questions in the second section were considered appropriate if they were consistent with the principles of the current evidence-based guidelines.9-12 The final section of the questionnaire looked into the obstacles that the respondents might have in applying evidence-based guidelines and their attitudes concerning any needs for a set of local guidelines. The questionnaire was developed, examined and discussed by three trainers in family medicine and one epidemiologist. A group of Year-4 medical students pilottested the questionnaire with 91 clinical tutors in family medicine at a response rate of 71%. It was finally revised, based on the problems observed in this pilot study. Descriptive statistics with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals were used to present the summarised responses. Results

Only 124 family physicians (9.6% overall response rate) completed and returned the questionnaire. Among these, most (n=80, 65%) were local Hong Kong graduates; the others were mainly from Europe (n=17, 13.8%) and Australia (n=12, 9.8%). The average number of years of post-graduate experience was 18.5 years (median = 17 years, ranging from 2 to 47 years) with a standard deviation of 11.4 years.

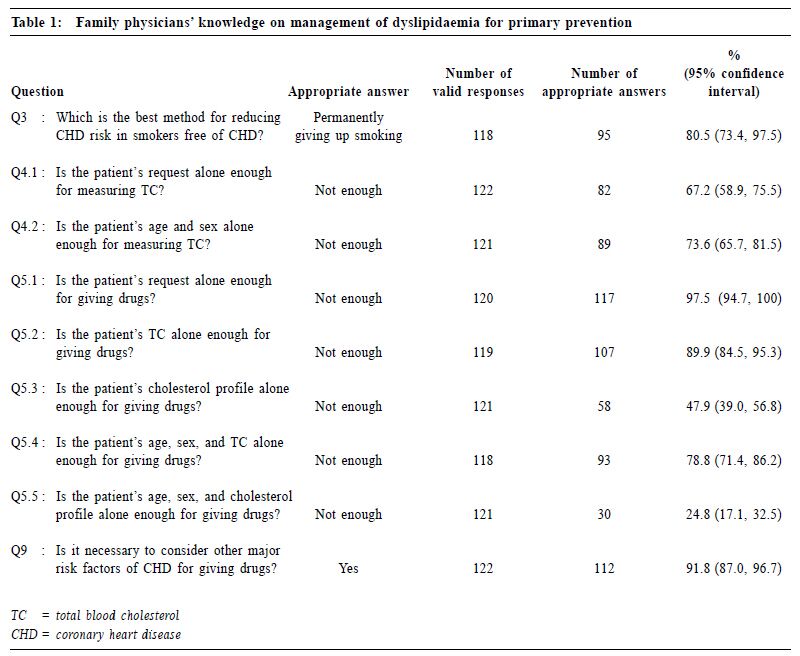

The majority of the family physicians correctly considered other risk factors (apart from a patient's request or the patient's age and sex) for measuring blood cholesterol (Q4.1 and Q4.2, Table 1). Among measures of primary prevention of CHD (such as lowering the blood cholesterol and blood pressure with drugs), 80.5% correctly identified quitting smoking permanently as the most effective method for reducing the risk of CHD in CHD-free smokers. Most family physicians disregarded patient's request alone, total cholesterol (TC) alone, patient's age and sex, or any information less than these, as sufficient indication for lipid-lowering drugs. Great emphasis was given to the patient's lipid profile in the decision-making; slightly more than half of the family physicians would prescribe drugs based on cholesterol profile alone (Q5.3, Table 1). Only 21.2% would prescribe a drug based on patient's age, sex and TC, but 75.2% would do so if cholesterol profile replaced TC (Q5.4, Q5.5). These result indicated that about 25% of the family physicians preferred to have more patient information than just patient's age, sex and cholesterol profile before prescribing drugs. The current understanding is that other major risk factors including blood pressure, smoking status, and diabetes mellitus should also be considered in this decision-making. Thus, some patients may have been given drugs based on insufficient information.

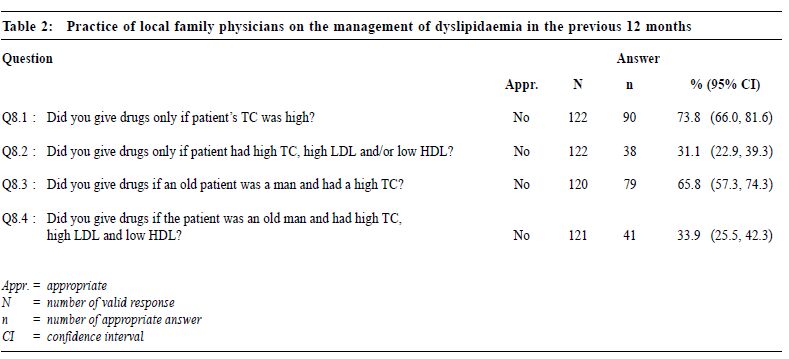

The vast majority of physicians (n=113, 91.9%) thought it necessary to consider other major factors of CHD in a person in order to make decisions on prescribing lipidlowering drugs (Q9). However, the validity of these replies is doubtful as this question was somewhat "leading", and the baseline to "other" was not specified. The family physicians estimated that they measured the TC in about 10%, and prescribed lipid-lowering drugs in about 5%, of their adult patients (Questions 6 and 7, Appendix). Of those whose TC was measured, 20% were done solely on patients' request and 70% of them were offered further classification of the cholesterol profile. The family physicians' stated practice in the management of dyslipidaemia in the previous 12 months was largely consistent with their knowledge (Table 2): prescription of lipid-lowering drugs was largely decided on a person's lipid profile. Responses to Questions 8.1 to 8.4 (pertaining to one's actual practice) were equivalent to responses to Questions 5.2 to 5.5 (pertaining to their knowledge) – i.e., the percentages of appropriate answers to the latter followed a similar pattern to the former. About 31% of family physicians did not prescribe lipidlowering drugs if a person had only a poor cholesterol profile (Q8.2, Table 2). This proportion was lower than the 47.9% of family physicians who believed that drugs should not be prescribed in such cases (Q5.3, Table 1). Similarly, given a poor lipid profile in an old man, the percentage of family physicians (33.9%, Q8.4) who considered drugs being unnecessary was greater (although not statistically significant) than those who actually did not give drugs in practice (24.8%, Q5.5).

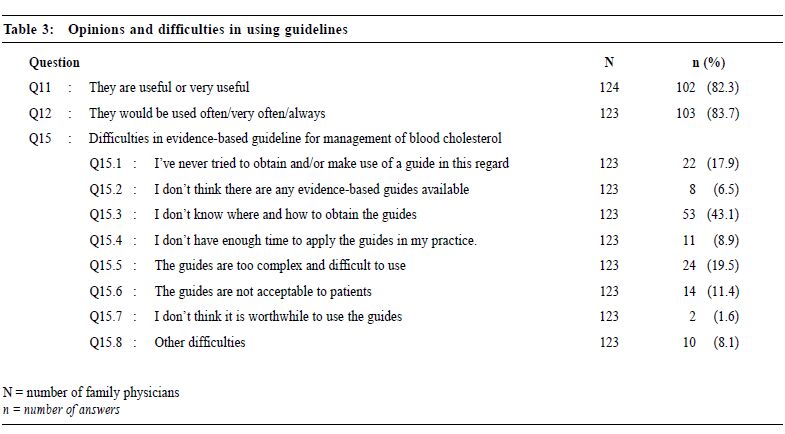

Age and sex were not considered as important as the lipid profile in deciding if a person needed drug treatment. In particular, 26.2% of family physicians would prescribe drug treatment to a person with high total cholesterol (Q8.1, Table 2). This latter percentage was not much different if a patient was a male and sufficiently old (34.2%, Q8.3); i.e., 31.1% family physicians would not prescribe drugs if a patient had only a poor lipid profile (Q8.2). Given further information on age and sex, only 33.9% would not do so (Q8.4). Of 107 valid replies, 53 (49.5%) did not know or had never used a risk assessment method (Q10). In 54 who had used a risk-assessment method, 26 used the Framingham risk table, 11 used the Sheffield table, and 17 used various other methods. Over 80% of 124 respondents agreed that guidelines were useful or very useful (Q11, Table 3) and that they would use them often or more frequently (Q12). There were 104 (84.6%) family physicians who expressed obstacles and difficulties in using guidelines: 75 (61.0%) had one principal difficulty, 20 (16.3%) had two problems, and 9 (7.3%) had three or more difficulties. The nature of difficulties encountered are summarised in Table 3. The main difficulty was acquiring the necessary skill in guideline application: how to obtain a guideline (Q15.3), how to implement one (Q15.4, Q15.5), and how to involve the patients (Q15.6).

Nearly all the respondents (120 out of 123, 98%) wanted an updated evidence-based guideline for dyslipidaemia management. Most (n=118, 96%) would accept a locally developed evidence-based guideline if such was available. A hardcopy table was the most preferred format for guideline access (n=98, 80%) as compared with a user-friendly computer program (n=14, 11%) and a pocket-sized calculator (n=11, 9%). Discussion Over 80% of the family physicians who responded to this survey would take into account major risk factors of CHD other than serum cholesterol in the management of blood lipid for primary prevention. The importance of quitting smoking in the primary prevention of CHD13 was well recognised by the family physicians. These broad principles are consistent with the recommenda-tions of the early international management guidelines on lipid management for primary prevention of CHD. However, there are suggestions that (a) pertinent details of risk factors are not adequately recognised, and (b) the practice of overall assessment is not fully observed so that patients might have been given drug treatment based on insufficient information for arriving at such a decision. Another important observation of this study relates to the physicians' views concerning the clinical guidelines of lipid management. Nearly all the family physicians would like to have a copy of evidence-based local guidelines on lipid management. A single sheet of paper containing a tabled guideline was the most preferred format. Until a more appropriate local guide becomes available, readers may find useful information from the recommendations by the Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology, European Atherosclerosis Society and European Society of Hypertension.10 In order to apply the new guidelines, the New Zealand Risk Assessment Table14 or the Sheffield Risk and Treatment Table15 can be used to project a patient's future risk of CHD. It is worth pointing out that the threshold of CHD risk above which lipid-lowering drugs would be fully justified is arbitrary and context-dependent. Local doctors may have to make a decision on the threshold more suitable for their own patients until a local reference is available. For this reason, the New Zealand risk assessment table is more useful as it provides an estimate of the risk and confines to no thresholds. In contrast, the Sheffield table can only be used when the fixed risk thresholds are considered appropriate for the patients. It seems that the importance of other major CHD risk factors in deciding the appropriate management of dyslipidaemia has been appreciated by the responding family physicians. Due to various obstacles and difficulties, the riskapproach has, however, not been widely applied in actual practice. The cholesterol profile-approach was still a common practice. The major obstacle for these family physicians in using evidence-based guidelines was a stated lack of skill in obtaining, appraising and applying the guides to their own practice. This is hardly surprising as these skills are exactly what today's evidence-based medicine requires but were inadequately covered in past medical curricula. These results suggest a need to promote, among physicians and the public, the concept and practice of the risk-approach in lipid management for primary prevention of CHD. By so doing, the cost-effectiveness of cholesterol treatment can be improved in that many unnecessary but costly prescriptions can be avoided and undue anxiety in the patients and their families due to the negative labelling effects can be reduced. This study also suggests the need and value of training in clinical epidemiology and critical appraisal skills in order that local practitioners can appropriately use current guidelines. A significant limitation to this survey was its low response rate. It is often difficult to obtain a high response rate in surveys of this kind. A slightly higher response rate (11.2%) was achieved in a local similar survey in 1994 in which the recruitment period was much longer (after extension) and reminders sent.16 Surveys that attempt to assess physicians' knowledge can give misleading results. The respondents may be only representative of a more confident group with better-than-average knowledge and skills in the relevant content. One half of our respondents were 17 years or more after their graduation from medical school, suggesting that more experienced (though not necessarily more knowledgeable) physicians were sampled. Due to the possible selection bias and the relatively small sample size, we focus this report on the respondents' overall information and general trends, leaving aside subgroup analysis such as the association between their professional profiles and the stated knowledge/ practice. Conclusion The family physicians who responded to this survey were aware of the principle of the overall risk of CHD when prescribing cholesterol lowering drugs for primary prevention. However, due to various obstacles and difficulties, there appeared to be a gap in their actual prescribing practice. Most family physicians welcomed the development of a local guideline but many indicated they had a need for training in clinical epidemiology and critical appraisal skills that are crucial to the practice of evidence-based medicine. Acknowledgement We would like to thank very much the physicians who cared to return their questionnaires. Their contribution provides readers, whether from family practice or not, some ideas of what could be done to improve the management of dyslipidaemia in primary care practice. We sent a copy of one-sheet coloured chart on the overall assessment of risk factors of CHD14 to each of the physicians who identified themselves in the returned questionnaires. Key messages

Y T Wun, MBBS, MPhil, MD, FHKAM(Family Medicine)

Associate Professor, J L Tang, MD, PhD Associate Professor, Department of Community and Family Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. D V K Chao, MBChB, DCH(London), FRCGP, FHKAM(Family Medicine) Chairman, Research Committee, The Hong Kong College of Family Physicians. Correspondence to : Dr Y T Wun, Department of Community and Family Medicine, 4/F, Lek Yuen Health Centre, Shatin, N.T., Hong Kong.

References

|

|