|

December 2016, Volume 38, No. 4

|

Update Article

|

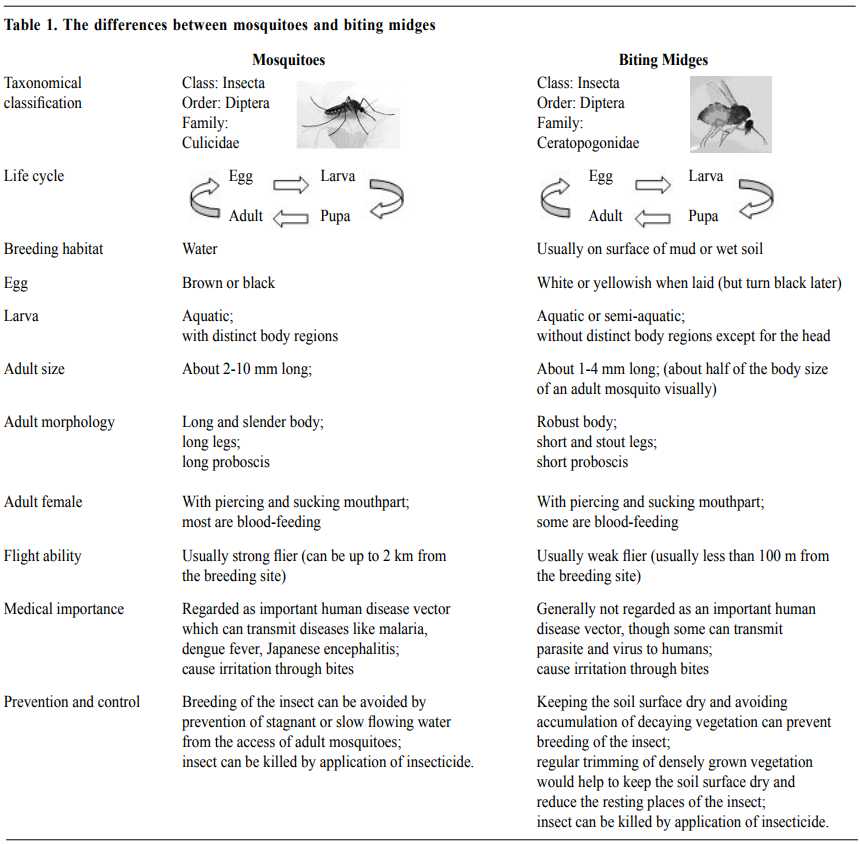

A review on the role of Culicoides biting midges in public health for the family physicianWai-man Yeung 楊偉民 HK Pract 2016;38:128-131Summary There has been recent increasing public concern about biting midges in Hong Kong. This review article provides family physicians with practical information for use during their consultations with patients. 摘要 香港公眾近來對蠓咬問題日益關注。本文為家庭醫生提 供實用資訊,可在診治患者時使用。 lntroduction For the last few years, there has been increasing public concern about biting midges (蠓). Patients may complain of very itchy skin lesions after being bitten by a tiny insect, which is no bigger than the punctuation mark on this page, and which sucks blood and what is the insect is not known to them. An upsurge of complaints about biting midge infestations in Hong Kong has taken place over the spring of 20161,2, and concerns whether these biting midges could ransmit diseases, and could even lead to fatal anaphylactic shock.3 This review article provides practical information for family physicians which they might find helpful during their consultation with their patients. What are biting midges? Biting midges are tiny flies belonging to the family Ceratopogonidae. Among the different genera of biting midges are Austroconops, Lasiohelea, Leptoconops and Culicoides which feed on blood of vertebrates including human. The most important of them is Culicoides.4 From a high diverse range of ecosystems, almost 1400 extant and extinct species of Culicoides have been described and the genus is present on all major land masses with the exception of Antarctica and New Zealand.5,6,7 The life cycle of biting midges consists of the egg, the larva, the pupa and the adult. Eggs are usually laid on the surface of mud or wet soil, especially those with plenty of decaying plant materials, which are the major food source for the larvae. Biting midge larvae are aquatic or semi-aquatic, and can live in both fresh and salt water. Other breeding sites include tree holes, semirotting vegetation and the cut stumps of plants. Adults are about 1-4 mm long with a dark body colour. They rest in dense vegetation and sometimes shady places. Their flight range varies, usually less than 100 meters from their breeding grounds. Although they have only short flight range, dispersal by wind is possible. While humidity plays a minimal role in the activity of biting midges, strong wind (over 5.6 km/hour) and low temperature (below 10°C) inhibit their flying. In fact, biting midges are such fragile insects that cool and dry weather can shorten their life span. Adults usually emerge in the summer causing much nuisance for humans. Only female adults bite for the extra nutrients which is needed to stimulate the maturation of eggs. Biting activity varies among species but they are most active during day time, near sunrise and sunset. With short mouthparts, biting midges are unable to bite through clothing. Exposed body parts such as hands, arms, legs (when wearing shorts) and the head are most commonly attacked. Biting midges rarely bite indoors.4 What is the impact of Culicoides biting midges on human health? In general, Culicoides biting midges are not considered as important human disease vectors. Only an extremely small proportion of Culicoides species are said to be having a significant deleterious impact on human existence.8 To most people, the bites of biting midges can cause acute discomfort and irritation. The irritation can last for days, or even weeks. Scratching aggravates the itch and may lead to secondary bacterial infection and slow-healing wounds.4 There were reports of more severe cutaneous pruritic whealand- flare responses and permanent scarring.9,10,11 Culicoides have only rarely been implicated as the primary agents of pathogen transmission to or between humans. By far the most important current role of Culicoides biting midges in public health lies in their ability to biologically transmit the Oropouche virus (OROV), the aetiological agent of the febrile illness, Oropouche fever, between human beings.7,9 Oropouche fever causes symptoms similar to those of dengue with an incubation period of 4-8 days (range: 3-12 days). Symptoms include the sudden onset of high fever, headache, myalgia, generalised arthralgia, anorexia and vomiting. In some patients it can cause clinical symptoms of aseptic meningitis.12,13 OROV is widely distributed across a geographic range of South and Central America and the Caribbean, and is thought to include Brazil, Peru, Panama, Colombia and Trinidad, but has not to date been recorded in nearby Costa Rica, Venezuela or other Caribbean islands. Major OROV disease epidemics have largely centered upon Brazil, where thousands of clinical cases can occur and yearly incidence in humans is thought to be surpassed only by dengue among the arboviral pathogens. The lack of specificity of clinical symptoms, combined with a high background of febrile illnesses, hampers accurate reporting.8 So far, no direct transmission of the virus from human to human has been documented.12 There are also 2 other arboviruses that are transmitted by Culicoides biting midges, the Bluetongue virus and the Schmallenberg virus. Both of these mainly affect non-human animals and this is not of particular concern to human health.8 Apart from the above, there is also a number of filarial nematodes most notably Mansonella ozzardi, M. perstans and M. streptocerca9 which are of high prevalence in Latin America and the Caribbean14 and west and central Africa15 transmitted between humans by the biting midges, but the clinical manifestation of mansonellosis is commonly either mild or entirely asymptomatic. The species of biting midges found in Hong Kong are not documented to be carriers of filarial worms.4 What are the differences between mosquitoes and biting midges? Both mosquitoes and biting midges are frequent biters of humans, and biting midges are often mistaken for mosquitoes. They are, however, different. The differences are illustrated in Table 1, referenced from the webpage of the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department.16Control methods Almost all Culicoides require moisture-rich habitats for the development of their egg, larval and pupal forms. The availability of such environments are a key determinant in limiting distribution, abundance and seasonal occurrence.7 The upsurge in biting midge infestations may be related to changes in climate, land use, trade, and animal husbandry.17 Prevention and control depend on reducing the breeding of midges through source reduction (removal and modification of breeding sites) and reducing contact between midges and people.12 For the larvae midges, complete disinfestations could be difficult because of the extensive breeding places, it could be difficult for complete disinfestations. Nonetheless, reduction of breeding could still be achieved by a) keeping low moisture of soil surface by techniques like plough or draining; b) removing refuse, fallen leaves and other decaying vegetation as well as using choking matters (e.g. muddy soil) in sand-traps/surface drainage channel; c) trimming, on a regular basis, densely grown vegetation to increase the exposure of soil surface to sunlight and air; d) applying residual insecticide at breeding places.4 For the adult midges, they can be controlled by the spraying of knockdown insecticide (e.g. fogging). Regular trimming of densely grown vegetation can reduce the resting places of the adults. Personal protection measures should be employed, including installation of screens (mesh size < 0.75 mm), wearing long-sleeved clothing and applying insect repellents.4 Insect repellents can be man-made or made from natural materials. The active ingredients N, N-Diethyl-metatoluamide (DEET) and picaridin are conventional manmade chemical repellents. Oil of lemon eucalyptus, oil of citronella and Insect Repellent 3535 (IR3535) are repellents made from natural materials such as plants, bacteria, and certain minerals.18 Among the many different kinds of repellents, DEET had previously been the gold standard of choice.19,20 A recent study showed that for environmental exposures to disease-transmitting biting midges, topical insect repellents containing IR3535, picaridin, or oil of lemon eucalyptus (p-menthane-3, 8-diol or PMD) offer better topical protection than topical DEET alone.21 For individuals exposed to persistently high biting rates, repeated application of repellents becomes unfeasible due to dermatological reactions, and treated clothing and mechanical barriers such as netted hoods may provide a more convenient protection.22,23,24 Patients may be concerned about the use of insect repellents for children, for fear of the harmful effects of chemicals in the human body. The following advice can be offered to patients: Insect repellents containing DEET should not be used on children under 2 months of age. Oil of lemon eucalyptus products should not be used on children under 3 years of age. When applying insect repellents to children, avoid their hands, around the eyes, and cut or irritated skin. Do not allow children to handle insect repellents. When using on children, apply to your own hands and then put it on the child. After returning indoors, wash your child’s treated skin or bathe the child. Clothes exposed to insect repellants should be washed with soap and water.18

Advice to patients who had raised the concern of biting midges

Wai-man Yeung, FRCSEd, FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Medical & Health Officer Specialist Department of Family Medicine & Primary Health Care, Hong Kong East Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR, China. Correspondence to: Dr Wai-man Yeung, Medical & Health Officer Specialist, Sai Wan Ho General Out Patient Clinic, 1/F, Sai Wan Ho Health Center, 28 Tai Hong Street, Sai Wan Ho, Hong Kong SAR, China.

References

|

|