|

December 2015, Volume 37, No. 4

|

Update Article

|

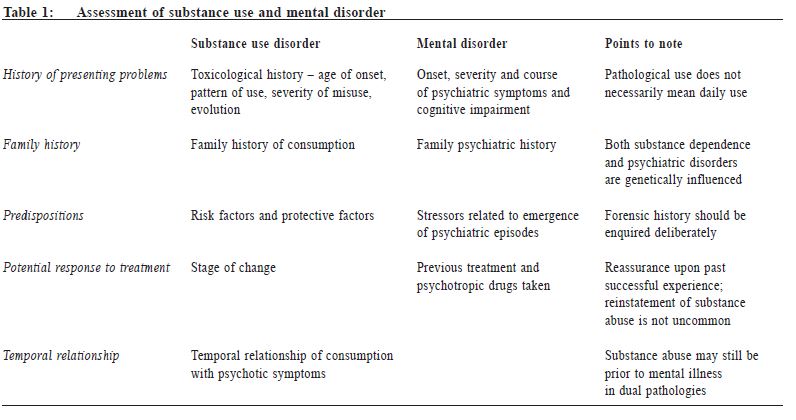

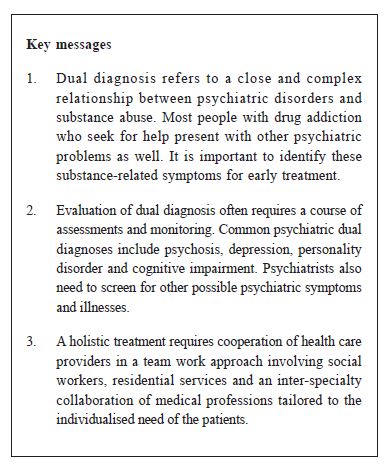

Dual psychiatric diagnosis in substance abuse patientsJimmy Chi-wah Leung 梁智華 HK Pract 2015;37:135-142 Summary This article will review the epidemiology and assessment of common dual psychiatric diagnosis in patients with substance abuse, and explore the key roles of primary care physicians and other health professionals in a multi-disciplinary team approach. 摘要 本文評述患有常見雙重精神障礙濫藥病人的流行病學及對其徵狀之評估,並探究基層醫生及其他醫護專業在多元學科團隊中的角色。 lntroduction It has long been known that a close and often complex relationship between psychiatric disorders and substance abuse exists. The terms ‘comorbidity’ and ‘dual diagnosis’ have been used interchangeably to describe the occurrence of more than one disease or disorder in the same individual. Various conceptualisations of comorbidity have been suggested, and they include viewing symptoms as parts of one and the same clinical syndrome, as parts of two or more separate conditions, or as involving substance-induced or independent syndromes, and/or primary or secondary disorders. 1 Dual diagnosis in psychiatry is traditionally defined as the occurrence of substance use disorder (SUD) in patients with severe mental illness. In recent times, however, the notion of dual diagnosis has been expanded to the occurrence of any mental illness (e.g. depression) along with an SUD.2 Patients with dual diagnosis often have more severe symptoms and impairment, as well as poor functioning and worse long-term prognosis than patients with a single disorder. Epidemiology The United States Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study conducted in the early 1980s serves as the first landmark epidemiological study, which reported a lifetime prevalence of 22.3% for alcohol use disorder (AUD) in those with a psychiatric disorder, 2.3 times more than those without any psychiatric disorder. In addition, the lifetime prevalence of other drug use was 14.7%, 4.5 times more than those without any psychiatric disorder.3 The National Comorbidity Survey (NCS)4 indicated that 41% - 65.5% of individuals with a lifetime SUD also had a lifetime history of at least one other mental disorder. Alternatively, around 50% for those with a lifetime mental disorder had a lifetime history of at least one addictive disorder. Those with schizophrenia had nearly 4 times greater likelihood of having lifetime AUD (24%) and SUD (46%). The reported rates of comorbidity between SUD and psychiatric disorders in many Asian countries are lower than the rates in western countries. A large epidemiological study (> 60,000 subjects screened) in China5 showed that the one-month prevalence of any mental disorder and SUD were 17.5% and 5.9% respectively. The rate of dual diagnosis of SUD and a mental disorders was extremely low. The World Mental Health Survey in Japan (WMHSJ)6 also revealed extremely low rates of illicit drug use (1.5% and 0.3% respectively for cannabis and cocaine) in the general population. A local study on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and SUD7 reported rates of illicit drug use in ADHD children and controls were 3% and 0% respectively. The substantial regional difference between Asian and Western countries may reflect socio-cultural, genetic and geographic differences in the availability of psychoactive substances, regional legislations and public health policies governing their us e. Assessment Assessing substance abuse Family physicians' role as gatekeepers put themselves in a pivotal position in screening for and identifying substance-use related symptoms and providing information about risks and problems. Apart from the biological markers like urine and hair drug testing, screening can be conducted with self-administered questionnaires which provide sensitive and inexpensive means of detecting potential drug-related problems. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) version 3.0 is a commonly used 8-item questionnaire which assesses the pattern, problems, risks and dependence of patients’ substance use, within the previous 3 months, and helps differentiate people who are abstainers, problem users or dependents. Assessment of psychiatric disorders A number of obstacles are postulated to exist in causing ambiguities in the recognition, ascertainment and treatment of dual diagnosis. Accurate reporting and clinical assessment may be further complicated by the wide symptom overlap between psychiatric disorders, and the effects of substance abuse, other aspects of mental state or cognitive impairment. Structured assessment tools such as PRISM (psychiatric research interview for substance and mental disorder) are available for distinguishing substance-induced and mental disorders. However, because they are not commonly used in the clinical setting, usual practice requires obtaining a substance abuse history, the presentation of symptoms, course of symptoms and temporal relationships. (Table 1) Psychiatric disorders and substance abuse a) Substance abuse and psychosis The key principle of management is accurate diagnosis with long term monitoring in order to formulate a multifaceted and realistic plan with the patient and to establish goals of treatment that are personally meaningful to them. The lifetime association of schizophrenia with SUD is high. Persons with schizophrenia have an odds ratio of 3.3 and 6.2 for developing alcohol abuse and other SUDs respectively.8 Patients reported improved mood, sense of energy and clearer thinking after stimulants use.9 Yet, those patients with coexisting substance abuse usually present with more positive symptoms, higher rate of impulsive and aggressive behaviour10, lower medication compliance11,higher need for emergency care, police arrests and risk of victimisation.12

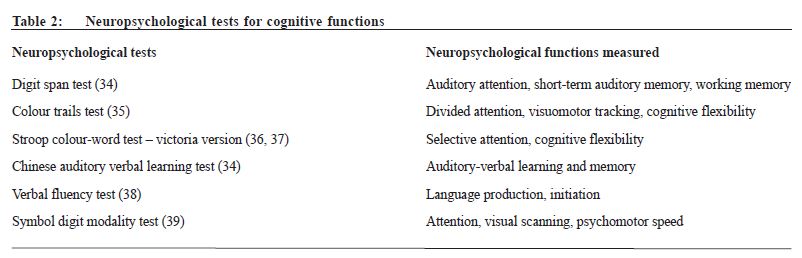

Methamphetamine (MA) abusers commonly have induced psychotic symptoms. This is characterised by a paranoid hallucinatory state that develops gradually with repeated MA abuse and continues after intoxication. The picture is similar to schizophrenia with formal thought disorder and cognitive impairment13, but with less negative symptoms like alogia or flattening affect. Longitudinal studies report that as many as 10% of chronic MA users develop a persistent psychotic disorder, while at least 23% develop clinically significant psychotic symptoms.14 A more integrated treatment-approach, involving the use of medications for both psychosis and substance abuse, coordinated psychotherapy, and psychosocial treatments matching the motivation of the patient, has been recommended.15 b) Substance abuse and cognitive problems The relationship between substance use and cognitive function is complex and is affected by multiple factors including stage of use (e.g. active use / recent relapse /early abstinence / prolonged abstinence), psychiatric and physical comorbidities, and motivation of patients during cognitive assessments. Yet many studies have demonstrated that substance abuse especially with chronic stimulant use is associated with deficits in cognitive functioning such as decision making, response inhibition, planning, working memory and attention. These cognitive functions, particularly inhibitory cognitive control, are attributed to the prefrontal cortex and linked closely to addictive behaviour itself. Therefore, treatments optimising cognitive functions, in particular those related to impulsivity, behavioural flexibility, or to attenuate drug reward are potential effective treatments for addictive disorder.16 A comprehensive neurocognitive screening and assessment in the early stage of treatment would help instill insight of patients into substance abuse problem and enhance their motivation to quit. Table 2 illustrates some of the common neuropsychological tests for cognitive functions. c) Substance abuse and personality disorder Personality disorder is defined as an enduring pattern of inner experience and behaviour manifested in cognition, affectivity, interpersonal functioning, or impulse control that leads to clinically significant distress or impairment. According to the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10), personality disorder could be categorically classified as follows: ICD-10 classification of personality disorder - Paranoid: sensitive, suspicious, preoccupied with conspiratorial explanations, self-referential, distrust of others. - Schizoid: emotionally cold, detachment, lack of interest in others, excessive introspection and fantasy. - Schizotypal (classified under schizophrenia and related disorders): Interpersonal discomfort with peculiar ideas,perceptions,appearance and behaviour. - Dissocial: Callous lack of concern for others, irresponsibility, aggression, inability to maintain enduring relationships, disregard and violation of others’ rights, evidence of childhood conduct disorder. - Emotionally unstable – impulsive type: inability to control anger or plan, with unpredictable affect and behaviour. - Emotionally unstable – borderline type: unclear identity,intense and unstable relationship pattern,threats or acts of self-harm,impulsivity, quasi-psychotic experience. - Avoidant: self-consciousness, fear of negative evaluation by others, timid, insecure. - Anankastic: doubtful, indecisiveness, cautious, rigidity, perfectionism, preoccupation with orderliness and control. - Dependent: Clinging, submissive, excess need for care, feel helpless when not in relationship.

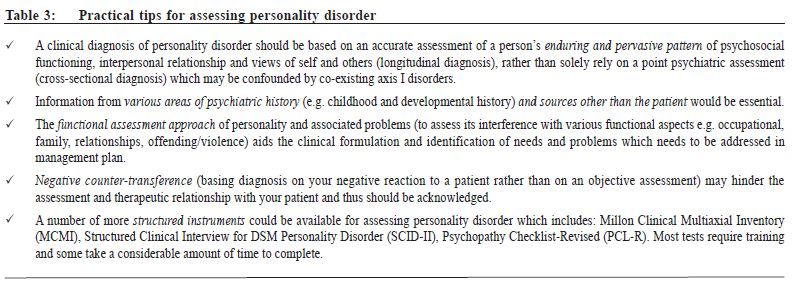

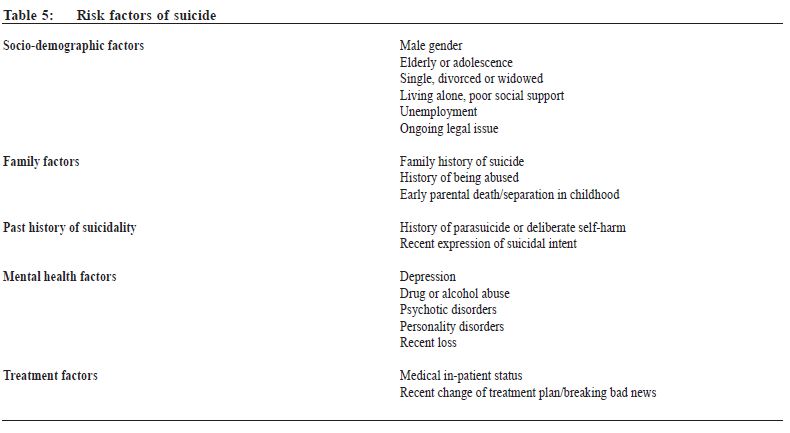

Personality disorder, in particular the dissocial subtype, is traditionally known to be highly associated with substance abuse. However, there is increasing evidence indicating that a broader range of personality disorders, namely the borderline and schizotypal type, should be addressed to better understand the aetiology and course of SUD.17 Table 3 describes some of the practical tips in the assessment of personality disorders. d) Substance abuse and depression There is a strong association between major depressive disorders (MDD) and SUD with a described prevalence of 12% to 80%.18,19 Coexisting MDD and SUD poses a worse clinical course, poorer response to treatment, a worse prognosis for both disorders, and more importantly, an increased likelihood of suicidal ideation, serious suicidal attempts, and completed suicide.20,21 In clinical practice, delineating the diagnostic and causal relationship between MDD and SUD is crucial since this helps in determining the therapeutic strategy to be used. From a pathogenic point of view, MDD and SUD share similar mechanisms, and the genetic and environmental factors are important in the neurobiological mechanisms involved in their pathogenesis.22 Table 4 describes some of the factors aiding the diagnostic process. Although depression can be associated with abuse of various psychoactive substances, more data are available for alcohol use disorder (AUD). Current evidence suggests a common genetic predisposition for both alcoholism and depression.23-25 Prognostically, alcohol contributes to a significant number of deaths from suicide in depressive patients.26 Suicidal ideation is also more common in comorbid patients than merely depressive cases.27 Results from the meta-analysis conducted by Nunes and Levin showed that: 1) antidepressants are effective in treating depressive episodes when used in appropriate doses for longer than 6 weeks, especially in cases of confirmed depression; 2) antidepressants have little effect on the maintenance of abstinence.28 While antidepressants are effective in treating acute depression reducing the use of the addictive substances, there was no effect on abstinence or total remission. Thus, a specific and concomitant treatment for SUD is required. The literature supports the use of medications even in the actively drinking alcohol-dependent individuals with a dual diagnosis.29 Other topics in substance abuse Substance abuse and parasuicide assessment Substance abuse is an important risk factor for suicide, and should be included as one of the many coexisting risk factors that should be assessed in suicide evaluation. Parasuicide, which is a deliberately undertaken act that mimics suicide but does not result in death, should also be identified. An effective risk assessment requires three-way collaboration between the service user, carers and the care team. Documentation of process of decision making based on the best available information should be appropriately made.

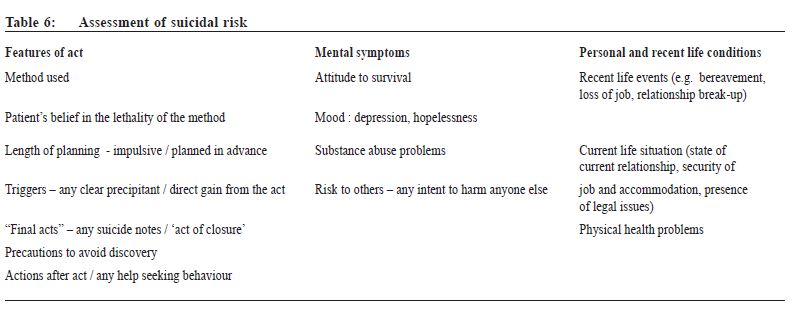

After overdose or other deliberate self-harm, assessment should encompass the suicidal act itself, the patient’s mental state and recent life events, past medical and psychiatric history, any behavioural disturbance or withdrawal/delirium features, as well as collecting collateral information. In some cases assessment of the parasuicide and future risk may need to defer until conscious level is full and adequate information is available. It may also be easier for the assessment to move from the factual history towards the emotional descriptions of the act itself after rapport building. Table 6 depicts some of the areas for assessments.

Substance abuse in adolescents and young adults It has long been argued that substance abuse is primarily an adolescent-onset disorder. Studies using a life course perspective revealed prevalence of substance abuse rises through the teen years, peaking at around 20% between age 18 and 20, then declined gradually over the next four decades. It was also been noted that over 90% of those who develop substance dependence in their lifetime started under the age of 18 and half started using under the age of 15.30 Thus, intervention during adolescent and young adulthood is an important strategy for reducing long-term use. The dopamine-rich reward pathway in meso-limbo-cortical system is still undergoing development in childhood and adolescence. Exposure to psychoactive substances during this critical period of development enhances the sensitivity of brain circuits to the reinforcing effects of drugs, which in turn leads to enhanced likelihood of repeating drug use, thus the risk of dependence.31 The relatively high level of impulsiveness and risk-taking behaviour among adolescents also increases the risk of their experimentation and use of substances. When faced in a clinical setting with an adolescent suspected of or known to have a substance abuse problem, it is important to integrate the assessment process with treatment decisions. The heterogeneity and number of different treatment issues suggest the need for comprehensive assessment and intervention in multiple systems including schools, workplace, child welfare systems and also the justice system.32 Dual diagnosis is usually presented in terms of co-existing externalising disorder like conduct disorder and ADHD, internalising disorder including depression, trauma-related disorders, anxiety disorders, history of victimisation, risky behaviour, violence, and drug-related illegal activities. A number of more structured assessment tools are available which include self-report scales (e.g. CRAFFT) and interviews (e.g. Teen Addiction Severity Index (T-ASI). The treatment philosophy described in the Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (A-CRA)33 provides a very good framework for care of ad olescent substance abusers, which advocates a non-confrontational, flexible and individualised approach based on one’s strength, motivation and environment. The key roles of primary care physicians and other professionals Treating drug abuse patients is never an easy task. Prevention and holistic treatment are important elements of management. A team work approach is therefore essential. Primary care physicians often act as their first medical contact point and are in a better position to monitor the physical health of those affected by prolonged use of alcohol and drugs. Early referral to secondary care mental health services is recommended for those with psychosis or suspected psychosis, significant impairment of functioning or social disruption. Other important members in the team include: 1) Substance Abuse Clinics under the Hospital Authority (SACs) – specialist psychiatric out-patient clinics accept referrals from social workers, voluntary agencies and other health care providers to offer services include medication treatment, counselling and in some cases, psychotherapy. 2) Counselling Centres for Psychotropic Substance Abusers (CCPSAs) – agencies run by social workers to provide a platform of information, counselling, and resource centres for other professionals who come across drug abuse clients in the course of their work. 3) Voluntary Residential Drug Treatment and Rehabilitation and Methadone Out-patient Treatment Programmes.

Apart from the above, the inter-specialty cooperation within the medical profession involving primary care and emergency physicians, urologists and psychiatrists is pivotal in many cases. A broad spectrum of available services in the community should be considered given the very different needs of clients and the limitation of each service. Conclusion The identification of substance-induced versus independent psychiatric symptoms or disorders has important treatment implications and often constitutes a challenge in our daily clinical practice. The high frequency of dual pathology has been well documented in clinical and epidemiological studies. Regrettably, many treatment trials for specific psychiatric disorders exclude patients with substance use disorder leading to underestimation of dual diagnosis and the treatment needs. The present review aims to provide an introduction and to raise clinicians’ awareness of the conditions. Acknowledgements I would like to express my thanks to Mr Paul Kong, clinical psychologist at the Kowloon East Cluster for his expertise information on the neuropsychological tests in substance abuse patients, and Ms Karen KW Yuen, year 5 medical student in University of Hong Kong for her contributions.

Jimmy Chi-wah Leung, MBChB(CUHK), MRCPsych(UK), MSocSc(Couns)(South Australia), FHKAM(Psychiatry)

Associate Consultant, Department of Psychiatry, Kowloon East Cluster, Hospital Authority Honorary Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong Honorary Clinical Supervisor, The Hong Kong College of Family Physicians Correspondence to: Dr Jimmy Chi-wah Leung, Department of Psychiatry, 1/F, Block P, United Christian Hospital, 130 Hip Wo Street, Kwun Tong, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China.

References

|

|