|

December 2015, Volume 37, No. 4

|

Original Article

|

Characteristics of female smokers and the predictors of quitting in a clinic based smoking cessation programme in Hong KongKS Ho 何健生,Helen CH Chan 陳靜嫻,Bandai WC Choi 蔡華智,Joe KW Ching 程錦榮 HK Pract 2015;37:123-133 Summary

Objective: This study aimed to explore the characteristics of local female smokers and the predictors of quitting.

Keywords: female smokers, predictors, characteristics, quit smoking 摘要

目的: 探索香港吸煙女性的特性和戒煙預示。

關鍵字:女吸煙人士,預示,特性,戒煙 Introduction

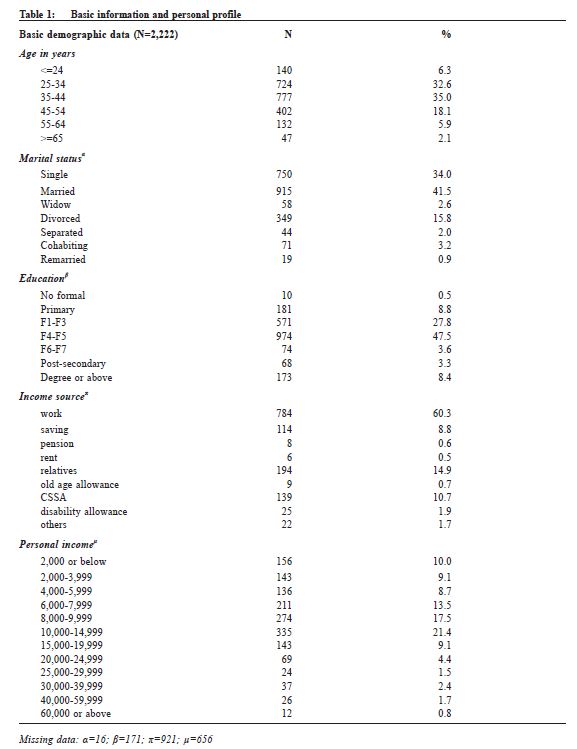

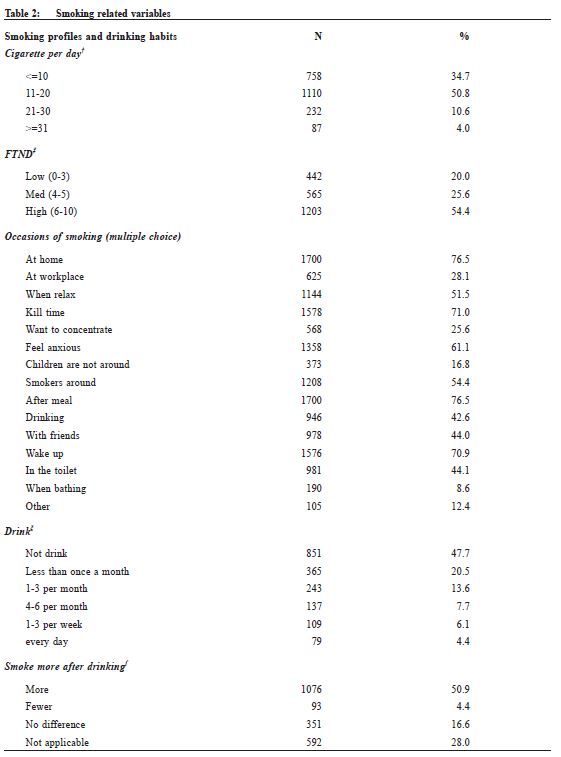

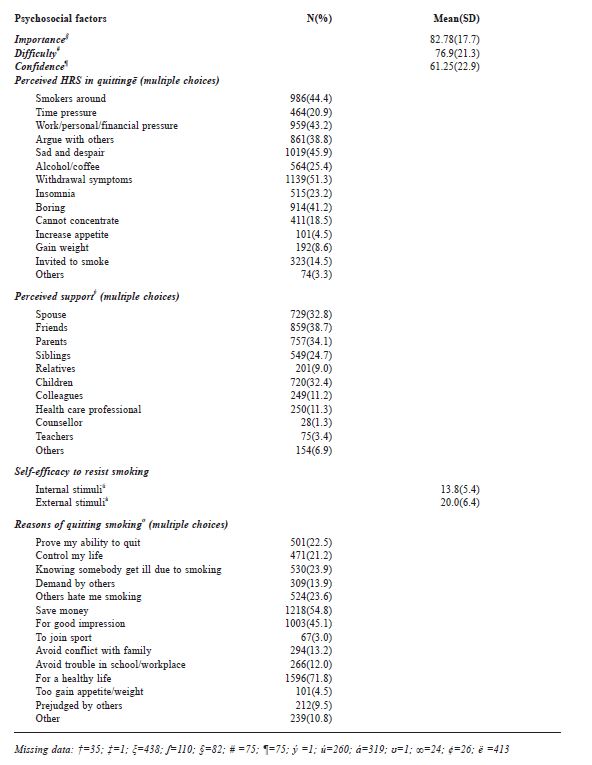

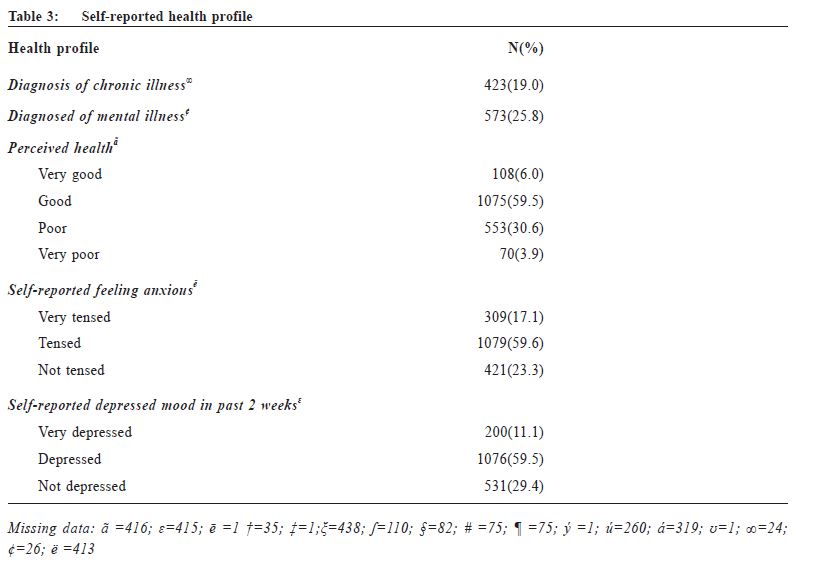

Smoking is the single most preventable cause of disease and premature death. Worldwide it is estimated that men smoke nearly four times as much as women although the ratios of female-to-male smoking prevalence rates vary dramatically across countries.1 While global male smoking rates have either reached a peak or are in a slow decline, the prevalence of tobacco use among women is, on the contrary, increasing. There is evidence that tobacco companies target their advertisement to females and adolescents in recent years. The ominous prediction is that by 2025, 20% of the female population will be smokers.3 This would mean that by 2025 there could be 532 million women smokers.4 There are numerous smoking related health risks specific to women, such as pregnancy related problems, breast cancer, cervical cancer and early menopause.5,6 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis also found that, compared with non-smokers, women smokers have a 25% greater relative risk (RR) of coronary heart disease than male smokers.7 Although the prevalence of female smokers in Hong Kong is only at 3%, the absolute numbers of female smokers is increasing, from 80,100 in 1998 to 96,800 in 2012 (Thematic Household Survey 1998 and 2012 by Census and Statistic Department of Hong Kong SAR). As a result there have been numerous calls for action on women’s tobacco use.8 There are relatively few data on the epidemiology of cigarette smoking in Asian women. A few local studies only involve focus group, telephone survey or a relatively small gender specific treatment programme initiated by the Women Against Tobacco Taskforce (WATT).6,9 As to the predictors of quitting, some overseas studies have demonstrated that women are less able to quit smoking than men.10 However, the predictors of quitting in female smokers are rather inconsistent. For example, education level has been found to be a predictor in some studies while in other studies it is not a predictor. Having a better understanding on the biological and psychosocial profiles of female smokers and the predictors of quitting will help offer more appropriate gender specific intervention. Methodology This study was a retrospective cohort study on female smokers and would observe their quit rate and factors related to quitting. All female patients attending any of the eight Tung Wah Integrated Centres for Smoking Cessation (ICSC) from 1 Jan 2010 to 30 June 2013 were included. Those who were mentally unstable or cognitively impaired were excluded. The ICSCs provided free pharmacotherapy and counselling service to smokers who were Hong Kong permanent residents. The integrated model of counselling and pharmacotherapy was adopted at all the centres.11 Counselling was conducted by registered social workers who were all trained in tobacco cessation. Motivational interviewing technique and cognitive behavioural therapy were used.12 The medications provided included both nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and non-NRT. Parallel intensive counselling sessions were given once a week for two weeks and then once every two weeks until the end of treatment phase which lasted from eight to twelve weeks. Smokerlyser by Bedfont Scientific Ltd was used to document tobacco abstinence at each visit. A structured questionnaire which had been tested and adopted by local researchers13,14,15 was given to consenting patients at the first visit to collect the following baseline information: (i) Socio-demographics variables (ii) Health-related variables (iii) Smoking-related variables: age started smoking, years of smoking, cohabiting with other smokers, cigarette per day, Fagerstrom Test on Nicotine Dependence (FTND) score, number and time of previous quit attempts, reason for quitting, high risk situations (HRS); (iv) Psychosocial variables (v) Smoking Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (SEQ-12).16,17 The questionnaire was self-administered; illiterate patients were helped by our staff to fill the questionnaire. Telephone follow up would be conducted at week 26 to ascertain smoking status. Data of all eligible participants from 1 Jan 2010 to and 30 June 2013 were reviewed. The outcome measure was self-reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence rate at week 26 through telephone follow-up. Those who were lost to follow-up were treated as non-quitters basing on an intention-to-treat analysis. Data analysis Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 22.0. Possible predictors listed above were described using descriptive statistics, in which categorical variables were expressed as percentages while continuous variables expressed as mean with standard deviations. Univariate logistic regression analysis was performed for all studied predictors. Predictors with p-value <0.10 were then included in multivariable logistic regression analysis. A p-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Results2,222 eligible cases were identified at the first visit, with zero patients meeting our exclusion criteria. The age ranged from 12 to 89 years with a mean of 38.6 (SD=10.9). 41.4% were married. 47.5% completed secondary school education and 8.4% had college degrees. 30.5% had a personal monthly income between HK$10,000 to HK$19,999, with a median of HK$8,000 to HK$10,000. 76.7% reported feeling tense. 70.6% reported having a depressed mood in the past two weeks while 25.8% reported to have mental diseases. 65.2% smoked more than 11 cigarettes per day. 54.4% had high FTND score (6-10). The mean score of self-perceived difficulty of quitting was 76.9 out of 100 (SD 21.3) and the mean score of self-perceived confidence was 38.8 out of 100 (SD 22.9). Perceived high risk situations (HRS) were mainly having smokers around (smokers who smoke in proximity), pressure from time, work, personal relationship and finance, feeling sad and despair, when arguing with others and when feeling bored. The quit rate at 26th week was 25.7% (n=571) and the response rate at 8th week was 83.8% (n=1862) and 26th week 74.4% (n=1653) (Table 1,2,3). Univariate analysis in Table 4 shows that the predictors of failure to quit are high FTND score, smokers in close proximity, time pressure, insomnia, feeling bored, feeling sad and despair, being invited to smoke, having alcohol and coffee, low internal efficacy and external efficacy, having mental illness, low confidence and anticipated high difficulty with quitting. Multivariable logistic regression shows that the independent predictors of quitting are having mental illness (adjusted OR 0.695, 95% CI 0.525-0.920), FTND (adjusted OR 0.978, 95% CI 0.960-0.996), time pressure (adjusted OR 0.653, 95% CI 0.452-0.943), sad and despair (adjusted OR 0.684, CI 0.491-0.952), smokers around (adjusted OR 0.657, CI 0.485-0.890), insomnia (adjusted OR 0.617, CI 0.437-0.871), perceived importance of quitting (adjusted OR 1.008, CI 1.001-1.016) (Table 5). Table 6 gives a brief summary of the predictors on quitting. Discussion Our study is a clinic-based female smoking cessation analysis and is to the authors’ knowledge the first study of this kind in Hong Kong. Conflicting evidence exists concerning the predictors of quitting for female smokers, and have been postulated to be related to methodological heterogeneity between studies with different populations and interventions.18,19 Our study tried to include a more comprehensive list of related variables for analysis. Many female smokers in Hong Kong regarded negative emotions and stress as important factors that influence continued tobacco use.6,20 Some studies indicated that social situation, work stresses, mood, and negative affect were more related to quitting in women.23 Our results are consistent with existing literature, showing that time pressure, feeling sad and despair, having mental illness were predictors of failure to quit. It is noteworthy that Bohadana A et al. has suggested that women smokers appear to have more behavioural component, and lower nicotine dependence than men; thus both nicotine and behavioural treatment should be tailored to women to increase their chances of abstinence.24,25,26 Socioeconomic status and tobacco dependence was found in previous studies to be predictors of smoking cessation21,22 In our study, level of tobacco dependence was a predictor while educational level was not. In fact, some studies also suggested that education level might not be a predictor in female smokers. Social support had been mentioned to be predictive of quitting in some studies.27 However, the Multi-site Lung Health Study revealed that the presence of support from spouse or friends was associated with better outcome among men but not in women.28 Our study also indicated that social support from friends, spouse and families did not give a better outcome in women. These differences might be due to variations in methodology,setting of the studies, cultures and different ethnic groups.

Our study involved a relatively large sample size with a more comprehensive, though not exhaustive, quit-related variables. The basic demographic differed slightly from the Smoking and Health Survey in Hong Kong Women by the Hong Kong Council on Smoking and Health (COSH) conducted in 2014 in that we had 6% less married women, 11.9% less secondary school leavers, 5% more employed women. 54% of our studied population had high FTND score whereas only 15.6 % of the COSH population had high FTND score. Since it is a clinic-based study, it can provide useful data for clinical practice. The limitations of our study are that the participants are more motivated smokers and they have relatively low median personal income. This might not represent the female smoking population as a whole. A small percentage of clients would re-enroll during the study period although we allowed re-enrollment only after one year had lapsed. However all bio-psychosocial characteristics of these clients would be assessed as a new case s ince things could have changed over the year. All treatments given were not randomised. The quit rates were self-reported and were not biochemically validated. However, it has been shown that in some studies, using self-reports to evaluate smoking appeared to be accurate.29 Job nature was not included in the variables for study. In fact the jobs of our client were very diverse and sample size for some jobs will be too small for subgroup analysis. Conclusion To improve the performance and efficacy of smoking cessation services, the study on the characteristics of local female smokers and the identification of predictors of success is crucial as it provides information for the service providers to match their intervention approach to different characteristics of smokers to yield better outcome. This study reveals that psychosocial factors are important predictors on the quit rate of female smokers. It also serves to create awareness among family physicians to take a gender-sensitive approach to help female smokers. In fact, an Australian study had pointed out that female smokers are less likely to receive opportunistic discussion on smoking cessation by family physicians during primary care consultations.30 Even in pregnancy, GP intervention rates are well below recommended levels.31 Women have higher rates of depression than men and are more likely to use smoking as a means of handling negative affect.32,33,34 It is important to screen for mental illness; help them cope with depressed mood and to monitor their mood during smoking cessation intervention. It is essential to counsel on avoidance of environmental cues associated with smoking, dealing with time pressure and insomnia apart from pharmacotherapy to tackle nicotine dependence.

KS Ho, MBBS, FHKAM(Family Medicine) FHKAM(Medicine)

Medical Officer TWGHs Integrated Centres on Smoking Cessation Helen CH Chan, MSo SC, MPH, RSW Supervisor TWGHs Integrated Centres on Smoking Cessation Bandai WC Choi, MSo SC, MPH, RSW Counsellor TWGHs Integrated Centres on Smoking Cessation Joe KW Ching, MBBS, FHKAM(Family Medicine) Medical Officer TWGHs Integrated Centres on Smoking Cessation

Correspondence to :Dr KS Ho, 17/F, Tung Sun Commercial, 194-200 Lockhart Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong SAR, China.

References

|

|