September 2010, Volume 32, No. 3 |

Original Articles

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Accuracy and completeness of ICPC coding for chronic disease in general outpatient clinicsLawrence CL Wong 王志龍, MK Lee 李文基, HT Mak 麥凱婷, PK Wong 黃柏鍵, KW Chung 鍾建榮, KH Wong 黃幗開, SM Tam 譚思敏, HW Li 李向榮, TB Chan 陳定邦, Kenny Kung 龔敬樂, Augustine Lam 林璨, Philip KT Li 李錦滔 HK Pract 2010;32:129-135 Summary Objective: To assess the accuracy and completeness of the International Classification of Primary Care Coding (ICPC) for chronic illnesses in the general outpatient clinics (GOPCs) and to identify common issues in coding for further improvements and implementation. Design: This is a retrospective review of case notes belonging to patients attending eight GOPCs. The data were obtained through the collection of the relevant data in the Hospital Authority’s computerized Clinical Management System (CMS). Subjects: A random sample of patients attended from the period: 1st December to 7th December 2008. Main outcome measures: The type and number of chronic illnesses of each case, and the accuracy and completeness of their corresponding ICPC coding. Results: 6095 (38.0% of total attendance) records were reviewed, of which 3274 (53.7%) patients had chronic illness. Overall 6608 chronic illnesses were identified, with a mean of 2.0 chronic illnesses per consultation. 75.4% of chronic illnesses were correctly coded. 19.4% and 5.3% were missed and wrongly coded respectively. The percentage of missing coding was positively correlated to the case complexity while the percentage of correct coding was inversely correlated. Conclusion: 24.7% of ICPC codes for chronic illness were either missed or wrongly coded. The commonly missed or wrongly coded ICPC was identified. Further study, such as focus group discussion or questionnaire for doctors, will be needed to explore the reasons and for further improvements. Keywords: International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC), general outpatient clinics (GOPCs), chronic disease, completeness, accuracy 摘要 目的: 評估普通科門診使用基層醫療國際疾病分類 (ICPC),做慢性疾病編碼的準確性和完整性,並找出其中常見的問題,以便進一步改善和施行。 設計:在八個普通科門診診所,通過醫管局的臨床資訊管理系統(CMS)收集相關資料,進行回顧性病歷研究。 對象:隨機抽取的2008 年12 月1 日至7 日期間到診病人的病例。 主要測量內容:每個個案的慢性疾病的類型和數量,以及其相應的國際編碼的準確性和完整性。 結果:共研究了6095 位病人的病例記錄,佔總就診人次的38.0% ,其中53.7% ,即3274 位患者有長期疾病。合共檢定6608 個慢性疾病,平均每次診治有2.0 個。75.4% 的慢性疾病被正確編碼, 19.4%和5.3%則分別被遺漏編碼或錯誤編碼。遺漏編碼的百分比和相關案例的複雜性呈正相關關係,而正確編碼的百分比則呈負相關。 結論:24.7% 的慢性疾病編碼發生遺漏或者錯誤 。已經確認了最常出現問題的慢性疾病編碼,需要做更深入研究,例如通過小組討論或醫生問卷調查以探討問題的原因及做進一步的改善。 主要詞彙:基層醫療國際疾病分類(ICPC),普通科門診,慢性疾病,完整性,準確性 Introduction The International Classification of Primary Care (revised version) (ICPC-2)1 coding was designed for the classification of patient’s reasons for encounter, health problems or diagnoses. ICPC coding is essential for the monitoring of clinical practice, clinical and administrative planning and implementation.2,3 An accurate and complete coding of ICPC facilitates future epidemiological data gathering, and is crucial in health services planning and research. Nevertheless, a recent audit in the Family Medicine Integrated Clinic illustrated that a high percentage of ICPC coding does not equate with a high ICPC coding accuracy and completenss.4 There was a clinical audit in the four primary care clinics of the Department of Health5, but there had been no similar studies in the Hospital Authority (HA) general outpatient clinics. Health services funding in HA’s in-patients is based on case complexity. Costs are expected to be higher for those with more complex disease combinations, which in turn attract greater resources from the government. If GOPCs (which form the major bulk of Hong Kong’s public primary care) future funding is to be based on case complexity or pay for performance, accurate and complete coding would be essential to ensure appropriate resources allocation. Furthermore, since patients with chronic illness comprise the majority among GOPC attendees (around 60% caseload from statistic s in the New Terrorities East Cluster6), priority must be given to the promotion of correct coding for chronic illnesses. Doctors working in GOPCs comprise a heterogeneous group of professionals, including community based family medicine trainees, higher family medicine trainees, doctors without any prior vocational training in family medicine, doctors with prior non-family medicine vocational training, and family medicine specialists. Trainees may have had the opportunity to receive training in ICPC coding through their structured educational programme (as part of their family medicine training requirement). Non-trainees would have received brief introduction on ICPC. However, they may not have formal training for ICPC coding and this is not in the undergraduate curriculum. Doctors need to input ICPC coding for each reason for encounter (RFE) at each consultation. There is no upper limit for the number of ICPC coding in each consultation and there is no prioritization for ICPC coding in the system. Doctors code ICPC at the highest level of their clinical judgment. That means they will code the disease only rather than the symptom, i.e. code (R74) upper respiratory infection acute, rather than (R05) cough. This study aims to assess the accuracy and completeness of ICPC coding for those with chronic illness in GOPCs and to identify the common errors in coding, with a view for future interventions to improve ICPC coding for chronic illnesses in GOPCs. Method Case review process Case notes belonging to patients attending eight general outpatient clinics in the HA New Territories East Cluster from 1st December to 7th December 2008 were reviewed. In each GOPC, one (for those with three or less consultation rooms) or two (for those with four or more consultation rooms) consultation rooms were randomly selected for patient sampling. Within that one week period, different days were again randomly selected. Consultation notes of all patients who received consultations in the selected rooms and days were reviewed. This was a retrospective study, and all attending doctors were blinded about the study. Case notes of patients with chronic illness were further assessed for the accuracy and completeness of the ICPC coding. Clinical notes were retrieved through the Clinical Management System (CMS), the computerized medical system used by the Hospital Authority. There were nine investigators in the study. Two of them were basic trainees of family medicine and the other seven investigators achieved Fellowships of Hong Kong College of Family Physicians or higher qualifications. In order to decrease the inter-investigators variation, standardization meetings were held before data collection. Each case was reviewed by one investigator. Regular standardization meetings were also held during the data collection period to discuss the problem arising during reviewing the consultation notes. Outcome variables For each patient episode, investigators derived presumptive diagnoses from the case notes and drug prescription, and matched these with the ICPC codes entered for that particular episode. Each code entered for that consultation was then classified into any of the three categories, discrepancies would be resolved by discussion and consensus among investigators:

a) chronic illness was defined as a condition that requires: Statistical analysis Based on an estimated GOPC attendance of 790,000 per year, and taking a confidence level of 95% and confidence interval of 5%, the minimum required sample size will be 384. Microsoft excel was used for all data entry and analysis. The correlation was calculated by Pearson correlation method. Results Number of presenting problems & chronic illness 6095 (38.0% of total attendance) case records were reviewed. Amongst these 3274 (53.7%) patients had chronic illness. Overall 6068 chronic illnesses were encountered, with a mean of 2.0 chronic illnesses encountered per consultation. For each consultation for chronic illness, there was on average an extra 0.6 other presenting problem. The percentage of coding for non-chronic illness RFE in patients with chronic illness was only 26.5%, i.e. 73.5% of non-chronic illness ICPC coding missing in patients attending for chronic illnesses with other reasons for encounter. Individual clinic data were shown in Table 1 for references.

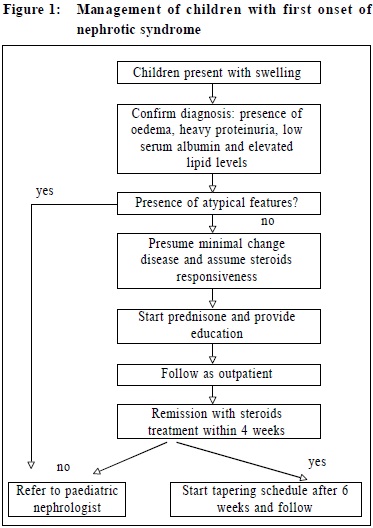

ICPC coding accuracy and completeness for chronic illness Among those with chronic illness, 98.8% had some form of ICPC coded, which included any acute or chronic, correct or wrong ICPC coding. However, only 75.4% of chronic illnesses were correctly coded. 19.4% and 5.3% of ICPC codes for chronic illnesses were missing and wrongly coded respectively. (Figure 1) Among those with missing codings, 43.2% (719) were considered to be in this category because drugs were prescribed for longer than four weeks but without related ICPC codes. Such medications include lubricating eye drops, antacids and analgesic balm.

ICPC coding accuracy and completeness, and case complexity The percentage of correct coding was inversely correlated with the case complexity. In this study, the number of chronic problems per patient ranged from one to six (Table 2), with a decreasing percentage of correct coding as the number of chronic problems increased (r = -0.7). Similarly the number of medications prescribed per consultation (ranging from zero to fifteen) was also inversely correlated with the percentage of correct coding (r = -0.67), as shown in Table 3.

The correctness of ICPC coding was strongly and inversely correlated to case complexity both in terms of the number of chronic problems per case (r = -0.95) and the number of medications prescribed (r = -0.97). On the other hand, the percentage of missing coding was strongly and positively correlated to the number of chronic problems in a case (r = 0.96) and the number of medications prescribed (r = 0.96). There was only a weak correlation between the percentage of wrong coding and case complexity (r = 0.31 for chronic problems per case, and r = 0.56 for number of medications prescribed). Coding accuracy and completeness for specific chronic illnesses The ten most commonly encounter ed chronic illnesses and their coding performance are shown in Table 4. The large majority had >50% correct coding frequencies. Uncomplicated hypertension, non-insulin dependent diabetes and lipid disorder were associated with the highest percentage of correct coding. On the other hand, complicated hypertension (K87) and cerebrovascular disease (K91) had the highest percentage of wrong coding (59.5% and 60.9% respectively). 152 out of the 153 patients coded as having uncomplicated hypertension (K86) actually had complicated hypertension (K87). 110 out of the 112 patients coded as having cerebrovascular accident (ie acute stroke) should have been coded with K91 (cerebrovascular disease).

Ischaemic heart disease without angina (K76) had the highest missing coding frequency (40.4%). The percentage of correct and wrong coding were 55.6% and 4.04% respectively. As for the results of the most common wrong code, most wrong codes were in the same categories as the correct ones. Benign prostate hypertrophy (Y85) was often wrongly coded as various urogenital symptoms (for examples, U02 urinary frequency / urgency, U07 Urine symptom / complaint other, U08 urinary retention, U29 urinary symptom / complaint other and Y02 pain in testis/scrotum) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (R95) was often wrongly coded as various other respiratory conditions (R79 chronic bronchitis, R96 asthma and R74 upper respiratory infection acute). Upper respiratory infection acute (R74), which was not a chronic illness, was wrongly coded among half of the top ten diseases: T90, T93, Y85, T86 and K76. Discussion This study revealed that GOPC doctors working at the review clinics assigned at least one code for the large majority of patients. However, the percentage of correct coding specifically for chronic illness was only 75.4%. 19.4% and 5.3% were missed and wrongly coded respectively. Case complexity appears to be an important association in relation to ICPC coding, as indicated by the strong correlation with the percentage of correct coding and missing coding. It is understandable that more coding errors will occur when the doctor has to deal with more problems during a consultation. It is unknown whether allowing more time for doctors to perform coding during their work will enhance coding accuracy and completeness, since time is obviously a factor to consider when dealing with more problems. On the other hand, doctors’ understanding towards ICPC appears to be particularly important for specific diseases, including complicated hypertension and cerebrovascular disease. These two entities are often wrongly coded as uncomplicated hypertension or stroke respectively. Although only slightly different in wordings, they represent entirely different stages of the same disease requiring different management and hence with different cost implications. It is possible that such errors in coding represent doctors’ habit of simply repeating what was coded in previous consultations. Ensuring high coding accuracy and completeness, not simply a high percentage of coding will enhance epidemiological data collection and subsequent health services planning. Disease coding in GOPCs was only implemented since their transfer to the HA in 2003 along with the introduction of CMS. At the same time CMS promoted computerization of clinical notes entry and medication prescription. However, technological advances created more non-clinical tasks, including appointment booking. Indeed, disease coding could be argued by some to be a form of non-clinical task. There is currently no direct link between doctors’ performance and services funding. This lack of incentive may prove to be crucial in improving disease coding accuracy and completeness in the future. There is growing of international interest in using financial incentives to improve quality of care. The US Institute of Medicine reported that “pay for performance should be introduced as a stimulus to foster comprehensive and system-wide improvements in the quality of care”.7 The number and the nature of diseases managed were part of the index for the “performance” of a clinic. An accurate and complete ICPC coding would be essential to reflect the performance and to ensure appropriate resources allocation. If incentives are not available , authorities will need to consider alternative measures to improve coding, such as the employment of staff specific for disease coding in Australia. Interestingly, although the percentage of coding for chronic illnesses is generally high, coexisting non-chronic illness RFE codings were frequently missing (73.5%). Postulated reasons for this discrepancy include GOPC doctors’ concentration on managing chronic illness, the self perceived lesser importance of acute conditions, doctors’ lack of knowledge in ICPC coding, and an inability to arrive at a relevant diagnosis for coding. Coexistence of chronic and acute conditions in one patient is not uncommon in the authors’ practice, but there is no data in Hong Kong to formally support this. Further studies will be required to delineate the reasons behind this discrepancy, with a view to enhance coding in these mixed conditions. Limitations and Future Implications Although this study was obtained from representative samples across all GOPCs in the HA NTEC, this may still not be representative of the more than 70 GOPCs in Hong Kong. Coding accuracy and completeness were based on investigators’ interpretation of computer case notes, which presumed that the case notes were of sufficient detail to reflect the actual consultation process. Further studies should be designed to assess the accuracy and completeness of ICPC coding across the whole territory, with assessment not purely based on consultation notes. In addition, qualitative studies to look at doctors’ views and knowledge towards ICPC coding should be performed so that future coding accuracy and completeness can be improved. Conclusion Despite a high percentage of ICPC coding in GOPCs, the percentage of correct coding for chronic illness was comparatively low. Health authorities should design new measures to enhance coding accuracy and completeness so that doctors will have a stronger incentive for correct coding which will eventually allow for improving epidemiological data gathering and health services planning. Key messages

Lawrence CL Wong, MFM (Monash), FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine) MK Lee, MBChB, FHKCFP, FRACGP HT Mak, MBChB, PK Wong, MBBS, Dip Med (CUHK), DCH (Ireland) KW Chung, MBChB, FHKCFP, FRACGP KH Wong, MBChB, FHKCFP, FRACGP SM Tam, FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine) HW Li, FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine) TB Chan, MBBS, FHKCFP, FRACGP Kenny Kung, MRCGP, FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine) Augustine Lam, FRACGP, FHKCFP, FHKAM (Family Medicine) Philip K T Li, MD, FRCP (Lond), FRCP (Edin), FACP Correspondence to: Dr Lawrence CL Wong, Family Medicine Training Centre, References

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||